Abstract

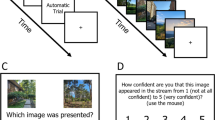

A melody’s identity is determined by relations between consecutive tones in terms of pitch and duration, whereas surface features (i.e., pitch level or key, tempo, and timbre) are irrelevant. Although surface features of highly familiar recordings are encoded into memory, little is known about listeners’ mental representations of melodies heard once or twice. It is also unknown whether musical pitch is represented additively or interactively with temporal information. In two experiments, listeners heard unfamiliar melodies twice in an initial exposure phase. In a subsequent test phase, they heard the same (old) melodies interspersed with new melodies. Some of the old melodies were shifted in key, tempo, or key and tempo. Listeners’ task was to rate how well they recognized each melody from the exposure phase while ignoring changes in key and tempo. Recognition ratings were higher for old melodies that stayed the same compared to those that were shifted in key or tempo, and detrimental effects of key and tempo changes were additive in between-subjects (Experiment 1) and within-subjects (Experiment 2) designs. The results confirm that surface features are remembered for melodies heard only twice. They also imply that key and tempo are processed and stored independently.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“Melody” is sometimes used to refer solely to successive pitch relations, as opposed to “rhythm”, which refers to differences in tone durations. Here, we define melody as a coherent series of tones that differ in pitch and duration.

For all pairwise comparisons, Cohen’s d was calculated using the average SD.

References

Abe, J.-I., & Okada, A. (2004). Integration of metrical and tonal organization in melody perception. Japanese Psychological Research, 46, 298–307.

Andrews, M. W., Dowling, W. J., Bartlett, J. C., & Halpern, A. R. (1998). Identification of speeded and slowed familiar melodies by younger, middle-aged, and older musicians and nonmusicians. Psychology and Aging, 13, 462–471.

Bartlett, J. C., & Dowling, W. J. (1980). Recognition of transposed melodies: A key-distance effect in developmental perspective. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 6, 501–513.

Bergeson, T. R., & Trehub, S. E. (2002). Absolute pitch and tempo in mothers’ songs to infants. Psychological Science, 13, 72–75.

Boltz, M. G. (1998). Tempo discrimination of musical patterns: Effects due to pitch and rhythmic structure. Perception & Psychophysics, 60, 1357–1373.

Boltz, M. G. (2011). Illusory tempo changes due to musical characteristics. Music Perception, 28, 367–386.

Boltz, M. G., Marshburn, E., Jones, M. R., & Johnson, W. (1985). Serial pattern structure and temporal order recognition. Perception & Psychophysics, 37, 209–217.

Brainerd, C. J., & Reyna, V. F. (2002). Fuzzy-trace theory and false memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11, 164–169.

Creel, S. C. (2011). Specific previous experience affects perception of harmony and meter. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 37, 1512–1526.

Dowling, W. J., & Bartlett, J. C. (1981). The importance of interval information in long-term memory for melodies. Psychomusicology, 1, 30–49.

Dowling, W. J., & Fujitani, D. S. (1971). Contour, interval, and pitch recognition in memory for melodies. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 49, 524–531.

Eerola, T., Järvinen, T., Louhivuori, J., & Toiviainen, P. (2001). Statistical features and perceived similarity of folk melodies. Music Perception, 18, 275–296.

Ellis, R. J., & Jones, M. R. (2009). The role of accent salience and joint accent structure in meter perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 35, 264–280.

Halpern, A. R. (1984). Perception of structure in novel music. Memory & Cognition, 12, 163–170.

Halpern, A. R. (1989). Memory for the absolute pitch of familiar songs. Memory & Cognition, 17, 572–581.

Halpern, A. R., Bartlett, J. C., & Dowling, W. J. (1995). Aging and experience in the recognition of musical transpositions. Psychology and Aging, 10, 325–342.

Halpern, A. R., & Müllensiefen, D. (2008). Effects of timbre and tempo change on memory for music. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61, 1371–1384.

Hyde, K. L., & Peretz, I. (2004). Brains that are out of tune but in time. Psychological Science, 15, 356–360.

Hyde, K. L., Zatorre, R. J., & Peretz, I. (2011). Functional MRI evidence for abnormal neural integrity of the pitch processing network in congenital amusia. Cerebral Cortex, 21, 292–299.

John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). The big five inventory—Versions 4a and 54. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research.

Johnson, M. K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Source monitoring. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 403–439.

Jones, M. R. (1987). Dynamic pattern structure in music: Recent theory and research. Perception & Psychophysics, 41, 621–634.

Jones, M. R. (1993). Dynamics of musical patterns: How do melody and rhythm fit together? In T. J. Tighe & W. J. Dowling (Eds.), Psychology and music: The understanding of melody and rhythm (pp. 67–92). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Jones, M. R., & Boltz, M. (1989). Dynamic attending and responses to time. Psychological Review, 96, 459–491.

Jones, M. R., Boltz, M., & Kidd, G. (1982). Controlled attending as a function of melodic and temporal context. Perception & Psychophysics, 32, 211–218.

Jones, M. R., Johnston, H. M., & Puente, J. (2006). Effects of auditory pattern structure on anticipatory and reactive attending. Cognitive Psychology, 53, 59–96.

Jones, M. R., Moynihan, H., MacKenzie, N., & Puente, J. (2002). Temporal aspects of stimulus-driven attending in dynamic arrays. Psychological Science, 13, 313–319.

Jones, M. R., & Ralston, J. T. (1991). Some influences of accent structure on melody recognition. Memory & Cognition, 19, 8–20.

Krumhansl, C. L. (1991). Memory for musical surface. Memory & Cognition, 19, 401–411.

Krumhansl, C. L. (2000). Rhythm and pitch in music cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 159–179.

Ladinig, O., & Schellenberg, E. G. (2012). Liking unfamiliar music: Effects of felt emotion and individual differences. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 6, 146–154.

Lamont, A., & Dibben, N. (2001). Motivic structure and the perception of similarity. Music Perception, 18, 245–274.

Levitin, D. J. (1994). Absolute memory of musical pitch: Evidence from the production of learned melodies. Perception & Psychophysics, 56, 414–423.

Levitin, D. J., & Cook, P. R. (1996). Memory for musical tempo: Additional evidence that auditory memory is absolute. Perception & Psychophysics, 58, 927–935.

Loui, P., Alsop, D., & Schlaug, G. (2009). Tone deafness: A new disconnection syndrome? Journal of Neuroscience, 29, 10215–10220.

McAdams, S., Vieillard, S., Houix, O., & Reynolds, R. (2004). Perception of musical similarity among contemporary thematic materials in two instrumentations. Music Perception, 22, 207–237.

Monahan, C. B., & Carterette, E. C. (1985). Pitch and duration as determinants of musical space. Music Perception, 3, 1–32.

Nygaard, L. C. (2005). Perceptual integration of linguistic and nonlinguistic properties of speech. In D. B. Pisoni & R. E. Remez (Eds.), Handbook of speech perception (pp. 390–413). Malden, MA: Oxford/Blackwell.

Palmer, C., & Krumhansl, C. L. (1987a). Independent temporal and pitch structures in determination of musical phrases. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 13, 116–126.

Palmer, C., & Krumhansl, C. L. (1987b). Pitch and temporal contributions to musical phase perception: Effects of harmony, performance timing, and familiarity. Perception & Psychophysics, 41, 505–518.

Peretz, I. (2008). Musical disorders: From behavior to genes. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 329–333.

Peretz, I., Brattico, E., Järvenpää, M., & Tervaniemi, M. (2009). The amusic brain: In tune, out of key, and unaware. Brain, 132, 1277–1286.

Peretz, I., Gaudreau, D., & Bonnel, A.-M. (1998). Exposure effects on music preference and recognition. Memory & Cognition, 26, 884–902.

Peretz, I., & Zatorre, R. J. (2005). Brain organization for music processing. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 89–114.

Plantinga, J., & Trainor, L. J. (2005). Memory for melody: Infants use a relative pitch code. Cognition, 98, 1–11.

Poulin-Charronnat, B., Bigand, E., Lalitte, P., Madurell, F., Vieillard, S., & McAdams, S. (2004). Effects of a change in instrumentation on the recognition of musical materials. Music Perception, 22, 239–263.

Prince, J. B., Schmuckler, M. A., & Thompson, W. F. (2009). The effect of task and pitch structure on pitch–time interactions in music. Memory & Cognition, 37, 368–381.

Prince, J. B., Thompson, W. F., & Schmuckler, M. A. (2009). Pitch and time, tonality and meter: How do musical dimensions combine? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 35, 1598–1617.

Radvansky, G. A., Fleming, K. J., & Simmons, J. A. (1995). Timbre reliance in nonmusicians’ and musicians’ memory for melodies. Music Perception, 13, 127–140.

Radvansky, G. A., & Potter, J. K. (2000). Source cuing: Memory for melodies. Memory & Cognition, 28, 693–699.

Reder, L. M., Donavos, D. K., & Erickson, M. A. (2002). Perceptual match effects in direct tests of memory: The role of contextual fan. Memory & Cognition, 30, 312–323.

Schellenberg, E. G. (1996). Expectancy in melody: Tests of the implication-realization model. Cognition, 58, 75–125.

Schellenberg, E. G. (2001). Asymmetries in the discrimination of musical intervals: Going out-of-tune is more noticeable than going in-tune. Music Perception, 19, 223–248.

Schellenberg, E. G., Iverson, P., & McKinnon, M. C. (1999). Name that tune: Identifying popular recordings from brief excerpts. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 6, 641–646.

Schellenberg, E. G., Krysciak, A. M., & Campbell, R. J. (2000). Perceiving emotion in melody: Interactive effects of pitch and rhythm. Music Perception, 18, 155–171.

Schellenberg, E. G., Peretz, I., & Vieillard, S. (2008). Liking for happy and sad sounding music: Effects of exposure. Cognition and Emotion, 22, 218–237.

Schellenberg, E. G., & Trehub, S. E. (1996). Children’s discrimination of melodic intervals. Developmental Psychology, 32, 1039–1050.

Schellenberg, E. G., & Trehub, S. E. (1999). Culture-general and culture-specific factors in the discrimination of melodies. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 74, 107–127.

Schellenberg, E. G., & Trehub, S. E. (2003). Good pitch memory is widespread. Psychological Science, 14, 262–266.

Schellenberg, E. G., & Trehub, S. E. (2008). Is there an Asian advantage for pitch memory? Music Perception, 25, 241–252.

Slavin, S. (2010). PsyScript (Version 2.3.0) [software]. Available from https://open.psych.lancs.ac.uk/software/PsyScript.html.

Smith, N. A., & Schmuckler, M. A. (2008). Dial A440 for absolute pitch: Absolute pitch memory by non-absolute pitch processors. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 123, EL77–EL84.

Stalinski, S. M., & Schellenberg, E. G. (2010). Shifting perceptions: Developmental changes in judgments of melodic similarity. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1799–1803.

Takeuchi, A. H., & Hulse, S. H. (1993). Absolute pitch. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 345–361.

Thompson, W. F., Schellenberg, E. G., & Letnic, A. K. (2012). Fast and loud background music disrupts reading comprehension. Psychology of Music, 40, 700–708.

Tillmann, B., Gossellin, N., Bigand, E., & Peretz, I. (2012). Priming paradigm reveals harmonic structure processing in congenital amusia. Cortex, 48, 1073–1078.

Trainor, L. J., Wu, L., & Tsang, C. D. (2004). Long-term memory for music: Infants remember tempo and timbre. Developmental Science, 7, 289–296.

Trehub, S. E., Schellenberg, E. G., & Nakata, T. (2008). Cross-cultural perspectives on pitch memory. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 100, 40–52.

Tulving, E., & Thompson, D. M. (1973). Encoding specificity and retrieval processes in episodic memory. Psychological Review, 80, 352–373.

Van Egmond, R., Povel, D.-J., & Maris, E. (1996). The influence of height and key on the perceptual similarity of transposed melodies. Perception & Psychophysics, 58, 1252–1259.

Volkova, A., Trehub, S. E., & Schellenberg, E. G. (2006). Infants’ memory for musical performances. Developmental Science, 9, 583–589.

Warker, J. A., & Halpern, A. R. (2005). Musical stem completion: Humming that note. American Journal of Psychology, 118, 567–585.

Warren, R. M., Gardner, D. A., Brubaker, B. S., & Bashford, J. A, Jr. (1991). Melodic and nonmelodic sequence of tones: Effects of duration on perception. Music Perception, 8, 277–290.

Weiss, M. W., Trehub, S. E., & Schellenberg, E. G. (2012). Something in the way she sings: Enhanced memory for vocal melodies. Psychological Science, 23, 1074–1078.

Wolpert, R. A. (1990). Recognition of melody, harmonic accompaniment, and instrumentation: Musicians vs. nonmusicians. Music Perception, 8, 95–106.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. Andrew Griffith, Monika Mankarious, and Elizabeth Sharma assisted in recruiting and testing participants. Rogério Lira helped in producing the figures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schellenberg, E.G., Stalinski, S.M. & Marks, B.M. Memory for surface features of unfamiliar melodies: independent effects of changes in pitch and tempo. Psychological Research 78, 84–95 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-013-0483-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-013-0483-y