Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the body of evidence of the effects of work-directed interventions on return-to-work for people on sick leave due to common mental disorders (i.e., mild to moderate depression, anxiety, adjustment disorders and reactions to severe stress).

Methods

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with an a priori developed and registered protocol (Prospero CRD42021235586). The certainty of evidence was assessed by two independent reviewers using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations.

Results

We reviewed 14,794 records published between 2015 and 2021. Of these, eight RCTs published in eleven articles were included in the analysis. Population: Working age adults (18 to 64 years), on sick leave due to mild to moderate depression, anxiety, adjustment disorders or reactions to severe stress. Intervention: Work-directed interventions. Comparator: No comparator, Standard care, or other measures. Outcome: return to work, number of days on sick leave, income. Overall, the effects of work-focused CBT and work-focused team-based support on RTW resulted in increased or faster return-to-work compared with standard care or no intervention (low certainty of evidence). The effects of Individual Placement and Support showed no difference in RTW compared with standard care (very low certainty of evidence).

Conclusion

Interventions involving the workplace could increase the probability of RTW. Areas in need of improvement in the included studies, for example methodological issues, are discussed. Further, suggestions are made for improving methodological rigor when conducting large scale trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Common mental disorders (CMDs) incorporate depression, anxiety and adjustment disorders (Fisker et al. 2022). These conditions affect about one in six people of working age and are a major cause of absence from work (OECD 2021). CMDs affect the individual not only in terms of suffering and the risk of social isolation, but also potential reduction in income. In medium- and high-income countries, the diagnosis of depression is associated with the highest societal burden due to disability, decreased ability to work and years lost due to premature death (European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA)). The likelihood of absence from work due to sickness is greater with respect to mental health problems, such as CMDs, than with physical health issues (Bryan et al. 2021). It is widely acknowledged that having paid employment offers significant health advantages (Marmot 2017; Modini et al. 2016; Schuring et al. 2017; van der Noordt et al. 2014). Consequently, it is crucial to implement effective interventions to support employees returning to work after sick leave.

At first glance, psychological and/or pharmacological treatment for CMDs would appear to be adequate interventions to reduce specific symptoms and decrease the duration of sick leave. However, these interventions have only a marginal effect on the duration of sick leave, return-to-work and other work-related outcomes (Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2020). As an alternative, involving the work-directed measures in the return-to-work process is a commonly suggested measure for improving return-to-work rates (OECD 2021). To meet the rehabilitation needs of employees on sick leave due to depression, anxiety, adjustment disorder (Arends et al. 2012; Hogg et al. 2021; Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2020), mental conditions (Dewa et al. 2015; Fadyl et al. 2020), common mental disorders (Mikkelsen and Rosholm 2018; Nigatu et al. 2016; Salomonsson et al. 2018), or a combination of mental or musculoskeletal conditions (Finnes et al. 2019a; van Vilsteren et al. 2015) several systematic reviews have evaluated the effectiveness of interventions involving work-directed measures, with reference to different outcomes.

Psychological interventions (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, CBT) are reported to have a small but significant effect in reducing sick leave (Finnes et al. 2019a), and a reduction in symptoms (Hogg et al. 2021; Salomonsson et al. 2018). Further, work-directed problem-solving interventions (based on CBT-principles) have shown a reduction in sick leave and increases in RTW outcomes (Arends et al. 2012; Dewa et al. 2015). A combination of workplace-, work-directed and clinical interventions has been evaluated in relation to sick leave, RTW and time elapsing until RTW (Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2020; Nigatu et al. 2016; van Vilsteren et al. 2015) with minor effects on absence due to sickness and RTW. To summarize, these interventions seem to have the potential to reduce the length of sick leave, and increase time to return-to-work. Still, at the 12 months follow-up or longer, the interventions are not more effective compared to the control conditions.

The current paper reports the systematic review of work-directed interventions, i.e., interventions involving several stakeholders (health care, employer) and the delivery of the intervention in direct contact with the employer or a representative of the employer (e.g., the employee’s supervisor, human resources representative or occupational health services) (Carroll et al. 2010). These interventions commonly aim to support employees on sickness absence by focusing on temporarily modification of work tasks, to overcome barriers for work participation, as well as decreasing symptoms, work disability, strengthen workability or work-related self-efficacy (Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2020).

As discussed above, previous systematic reviews have evaluated the effects in relation to work-related outcomes, revealing incongruent results. In this systematic review we have evaluated the effect of work-directed interventions (Carroll et al. 2010) aimed to support employees on sickness absence by focusing on temporary modification of work tasks, to overcome barriers to work participation, as well as reducing symptoms, work disability, strengthening workability or work-related self-efficacy (Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2020).

Hence, we addressed recent studies on work-directed interventions, with a broad range of work-directed interventions, including general labor market programs. In addition to RCTs, the presented review allowed for quasi-experiments. Further, our systematic review contributes to the knowledge base by providing an analysis of ethical aspects arising when introducing work-directed interventions involving the employee, health care and workplace.

Aim

To evaluate the body of evidence of the effects of work-directed interventions on return-to-work for people on sick leave due to common mental disorders (i.e., mild to moderate depression, anxiety, adjustment disorders and reactions to severe stress).

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement (Page et al. 2021) and the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services Method (sbu.se).

Protocol and registration

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with an a priori developed and registered protocol Prospero CRD42021235586 https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021235586. No deviations from the protocol were made.

Eligibility criteria

Randomized controlled trials, cluster-randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental observation studies and qualitative studies were included, provided they met the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Population

Working age adults (18 to 64 years), on sick leave due to mild to moderate depression, anxiety, adjustment disorders or reactions to severe stress.

Intervention

Work-directed interventions are defined as involving several stakeholders including at least health care services, the employer and the person on sick leave/employee and delivered in direct contact with the employer or a representative of the employer.

Comparator

No comparator, standard care or other measures.

Outcome

Primary: return to work, number of days on sick leave, and income. Secondary: health measures (sleep, depression, anxiety, stress, quality of life, capacity for work) and the experience of participating in work-directed interventions.

Language

English, Swedish, Norwegian and Danish.

Publication type

Original reports published in peer-reviewed journals, or elsewhere (so called ‘grey literature’).

Search period

1995 to 2021. The final search was conducted in February, 2022.

Exclusion criteria

Studies including newly arrived immigrants, post-traumatic stress disorder or severe mental illness were excluded. Studies reporting experiences of sick-leave were also excluded.

Search strategy and information sources

A systematic literature search was conducted in collaboration with an information specialist (CG). The following electronic databases were searched from 1995 to 2021 and the final search was conducted on February, 2, 2022: Medline (Ovid), Scopus (Elsevier), Ebsco Multi-Search (Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection; SocINDEX with Full Text; Academic Search Premier, ERIC); APA Psychinfo (Ebsco); Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest). The search terms were developed and defined in collaboration with the information specialist, and the authors (EBB, GF, EÅ, PST). The full list of search terms is presented in appendix 1. Additional searches of systematic reviews, health technology assessments reports and Swedish reports (‘grey literature’) were undertaken in Epistemonikos; International HTA Database, and KSR Evidence. The reference lists of included articles were searched, to identify additional studies. Articles included in systematic reviews were also checked for eligibility.

Selection process

Initially, two reviewers (EÅ,GF) independently assessed all retrieved records for relevance, by screening the title/abstract and excluding those not meeting the inclusion criteria. If in doubt, the record/abstract was included. Thereafter, two reviewers (EBB and PST) reviewed the abstracts for relevance. The assessments were registered in Rayyan https://www.rayyan.ai/. The potentially relevant articles identified by at least one of the reviewers were retrieved in full-text and their eligibility was assessed in terms of correspondence between the population, intervention, control, and outcome (i.e., PICO). All disagreements were discussed and resolved, if necessary, together with a third reviewer.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias (RoB) in each of the articles was assessed by two reviewers (EBB and PST) using the Cochrane RoB 2 tool (Sterne et al. 2019). Initially, the reviewers met and together reviewed 10 full text articles in order to calibrate their assessments. Thereafter, the reviewers assessed RoB independently. Reporting bias was not assessed because pre-published protocols reporting the design etc. of included studies were not available in all cases. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved by the reviewers together with a third reviewer if necessary. Articles with a low or a moderate risk of bias were included.

Effect measures

The fixed effects model was used in the meta-analysis, using Review Manager version 5.4. For binary outcomes, odds ratios, Cohens d and hazard ratios were reported. For continuous outcomes, the mean difference (MD) was used, while the Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) was applied if different instruments had been used to measure an outcome.

Synthesis methods

The included articles were summarized and described according to the participants’ characteristics, interventions, follow-up and the outcomes measured. Meta-analysis was conducted if the included articles were reasonably consistent, and the results adequately reported. The articles were categorized according to intervention and assigned to identical intervention categories. This resulted in three categories of intervention. When an outcome was reported by only one article, we conducted a synthesis without meta-analysis reporting MDs, effect sizes or hazard ratios.

Assessing the certainty of the evidence

The certainty of evidence was assessed by two independent reviewers, using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) (Balshem et al. 2011). The syntheses are shown in tables for Summary of Findings for each intervention type, presenting the total number of participants, the effects per study, certainty of evidence followed by reason/s for downgrading and comments on each outcome.

Results

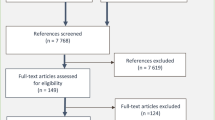

The literature search resulted in 14,794 records (see Fig. 1 for a flowchart), of which eight RCTs, published in eleven articles, were included (Bejerholm et al. 2017; Dalgaard et al. 2017a; Dalgaard et al. 2017b; Finnes et al. 2019b; Hellström et al. 2017; Hoff et al. 2022; Lammerts et al. 2016; Overland et al. 2018; Reme et al. 2015; Salomonsson et al. 2017; Salomonsson et al. 2020). Three studies were conducted in Sweden, three in Denmark, one in Norway and one in The Netherlands, all published between 2015 and 2021. The number of participants included in the studies varied between 61 and 1193, with a total of 2902, whom about 70% were female. The participants (median age between 34 and 46 years) were on part- or full-time sick leave. No adverse events were reported with respect to the interventions. The study characteristics are presented in Table 1, the interventions and comparisons in Table 2 and appendix 3 and 4. Reasons for exclusion are presented in appendix 2.

Three types of work-directed interventions

Based on our predefined description of work-directed interventions and in accordance with the interventions identified, the following intervention categories were defined:

Individual Placement and Support (IPS) is an employment support approach originally developed for severe mental disorders (e.g., psychosis, bipolar disorder). It involves supported job searching, paid placement, and on-the-job support for both the employee and employer. IPS has been adapted for mood and anxiety disorders as IPS-MA and Individual Enabling and Support (IES).

Work-focused behavioral therapy combines behavioral therapy techniques like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) with a focus on treating symptoms related to physical and/or psychological health issues and improving quality of life. Recent innovations include integrating a work-focused approach involving meetings between the patient, the supervisor, and therapist to address ability to work and to facilitate RTW.

Work-focused team-based support utilizes a multidisciplinary team comprising health care professionals (physicians, psychologists, registered nurses) and an RTW-coordinator specialized in rehabilitation and return-to-work. The team identifies the patient’s resources and barriers to the RTW process, providing support through a participatory approach, which involves stepwise meetings with the patient, the supervisor, and healthcare representatives.

Individual placement and support—summary of findings

Two studies, one from Denmark (Hellström et al. 2017) and one from Sweden (Bejerholm et al. 2017) evaluated the effects of IPS. The interventions analyzed in the studies varied somewhat and commonly dealt with coordination of stakeholder involvement (healthcare services, Public Employment Agency, Social Insurance Agency), counselling and on the job-training. The outcomes were competitive employment or education (Hellström et al. 2017) or employment rate (Bejerholm et al. 2017) measured at 12 (Bejerholm et al. 2017; Hellström et al. 2017) or 24 months (Hellström et al. 2017). A summary of the findings is presented in Table 3.

Hellström et al. (Hellström et al. 2017) evaluated IPS modified for people with mood and anxiety disorders (IPS-MA) compared to standard service containing: support from ‘job centers’ including for example courses, counselling, or job-training. The number and length of meetings were adjusted to the individual’s needs.

Bejerholm et al. (Bejerholm et al. 2017) compared Individual Enabling Support (IES) following the principles of IPS, with traditional vocational rehabilitation. The intervention lasted for 12 months. The support was based on motivational interviewing and cognitive strategies and was provided in accordance with ten IES principles, e.g., development of motivational and cognitive strategies, and competitive employment as a primary goal. The control group received traditional vocational rehabilitation delivered by different professionals and organizations.

Effects on return to work

The results show that at the 12-month follow-up, IES had a positive effect on the employment rate (Bejerholm et al. 2017). Hellström et al. reported that compoared to standard care, IPS-MA had no significant effects on competitive employment or education (Hellström et al. 2017) when compared to care as usual. Overall, the meta-analysis showed no significant differences from standard care (Fig. 2). However, the effect of Individual Placement and Support on return to work could not be assessed, mainly due to large confidence intervals (Table 3).

Effects on self-reported depression, anxiety, and quality of life

The effect of Individual Placement and Support on depression, anxiety, and quality of life could not be assessed, mainly due to the low response rate and incomplete data (Table 3).

Work-focused behavioral therapy—summary of findings

Seven articles, from Denmark, Norway and Sweden, reported the results of three studies evaluating the effects of CBT (Dalgaard et al. 2017a, 2017b; Overland et al. 2018; Reme et al. 2015; Salomonsson et al. 2017; Salomonsson et al. 2020) and one study evaluating the effects of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (Finnes et al. 2019b). A summary of the findings is presented in Table 3.

Overland et al. (Overland et al. 2018) and Reme et al. (Reme et al. 2015) compared work-focused CBT in combination with individual job support from the Norwegian Labor and Welfare Administration or other stakeholders (e.g., healthcare services). About 40% of the participants were on full-time sick leave, about 15% on part-time sick leave and 10% were unemployed. All participants in the intervention group received up to 15 sessions of CBT, and of those, 32% received individual support based on IPS principles.

Salomonsson et al. (Salomonsson et al. 2017, 2020) compared CBT, including an RTW-intervention with CBT. The number of sessions in the intervention- and control groups varied depending on the psychiatric disorder. A majority of the participants had symptoms of exhaustion and were absent due to sickness (duration from one up to six months part- or full-time).

Dalgaard et al. (Dalgaard et al. 2017a, 2017b) compared work-focused CBT, with a control group receiving clinical examination. The intervention included meetings at the workplace for discussion about modifications, for example workload or professional roles.

Finnes et al. (Finnes et al. 2019b) compared ACT, including a convergence dialogue, with standard care provided by primary healthcare or social services. The aim of the convergence dialogue with the workplace was to reach agreement about long- and short-term solutions in relation to RTW.

Effects on return to work

Compared to standard care or no intervention, work-focused CBT was shown to increase work participation by 6.2% units (Reme et al. 2015) after 12 months and also increase the probability of RTW after 44 weeks (Dalgaard et al. 2017a) (Table 3). Because the reported data were incomplete, it was not possible to undertake a meta-analysis.

The effect on absence due to sickness and income could not be assessed, mainly due to contradictory results and large confidence intervals or standard error (Table 3). Overall, it is possible that work-focused CBT may have a positive effect on RTW at 12 months follow up. A greater effect was observed for those on sick leave for longer than 1 year.

Effects on self-reported depression, anxiety and quality of life

Reme et al. and Finnes et al. measured symptoms of depression and anxiety using Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS). Work-directed CBT resulted in a decrease in depressive symptoms at the 12-month follow-up (Reme et al. 2015) and a corresponding effect of ACT at the 9-month follow-up (Finnes et al. 2019b) (Table 3). The interventions were adequately consistent and were therefore included in a meta-analysis. This showed that compared to standard care, work-focused behavioral therapy resulted in a reduction of depressive symptoms (Fig. 3). However, the effect of the interventions on anxiety was inconsistent (Fig. 3). Hence, no conclusions can be drawn about the effects of the interventions on the symptoms of anxiety compared to standard care. Overall, it is possible that work-focused behavioral therapy may reduce symptoms of depression at the 12-month follow-up. However, this effect should be interpreted with caution, as the level of depression is within the range of no depression. Thus, although this result shows a minor effect in terms of reduced symptoms of depression, it would appear to be of little clinical relevance. With respect to the effect on anxiety, the meta-analysis shows inconsistent results, with large confidence intervals. Hence, the effect of work-focused behavioral therapy on symptoms of anxiety could not be assessed.

Effect of work-focused behavioral therapy on a: depressive symptoms measured with Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, 9 (Finnes et al. 2019b) and 12 months follow-up (Reme et al. 2015); b: anxiety symptoms measured with Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, 9 (Finnes et al. 2019b) and 12 months follow-up (Reme et al. 2015); c: on quality of life measured with the EuroQOL five dimensions questionnaire (Reme et al. 2015) or Satisfaction with Life Scale (Finnes et al. 2019b; Reme et al. 2015). Comparisons received standard care

Furthermore, Reme et al. and Finnes et al. reported measurements of quality of life. Neither work-directed CBT at the 12-month follow-up (Reme et al. 2015), or ACT at the 9 months follow-up (Finnes et al. 2019b) had a significant effect on self-reported quality of life (Table 3). The meta-analysis indicated that compared to standard care, the interventions resulted in a minor, although not statistically significant, increase in quality of life compared to standard care (Fig. 3). Hence, the effect of work-focused behavioral therapy on reported quality of life could not be assessed, mainly due to a large confidence interval.

Work-focused team-based support—summary of findings

Two studies, from The Netherlands (Lammerts et al. 2016) and Denmark (Hoff et al. 2022) evaluated the effects of work-focused team-based support. A summary of the findings is presented in Table 3.

Lammerts et al. (Lammerts et al. 2016) compared a standardized form of occupational healthcare early after sick leave, with standard care provided by the Dutch Social Security Agency. Hoff et al. (Hoff et al. 2022) evaluated integrated vocational rehabilitation and mental health care, in addition to standard care, and compared this to standard care alone.

Effects on return to work

The interventions were sufficiently consistent, but the data were inadequately reported (only hazard ratios) (Lammerts et al. 2016). Hence, no meta-analysis was conducted. No effects on the number of weeks until RTW were reported from the two studies. However, in the Danish study, 56% returned to work after 12 months, compared with 46% in the control group. Thus, a narrative synthesis indicates that compared to standard care, work-focused team-based support may increase RTW (Table 3).

Effects on self-reported depression and anxiety

Lammerts et al. (Lammerts et al. 2016) and Hoff et al. (Hoff et al. 2022) included self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety, measured by the Four Dimensional Symptom Questionnaire and compared this with standard care at the 12-month follow-up (Hoff et al. 2022; Lammerts et al. 2016) (Table 3). The meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant reduction in depression associated with work-focused team-based support (Fig. 4). However, the effect should be interpreted with caution, as the levels of depression are within the range of no depression.

Overall, the effect of work-focused team-based support on symptoms of anxiety, stress, exhaustion, quality of life, and work ability, could not be assessed, mainly due to the wide confidence intervals and low response rate (Table 3).

Ethical aspects

Several ethical aspects were identified. Work-directed interventions might increase the individual’s feeling of guilt and shame: to a large extent the interventions focus on and are directed towards the individual’s mental health, rather than, for example, problems in the workplace. Further, work-directed interventions might affect the individual autonomy. Thus, pointing to questions whether participation was voluntary, whether an individual had the opportunity to control and select some details of the interventions. The issue of whether CMD-symptoms might be an obstacle to making informed and autonomous decisions must be considered. The work-directed interventions might affect personal integrity and the individual’s control over the flow of personal information. For example, work-focused team-based support included meetings between the patient, healthcare representatives and employer representatives. In this context, it might be difficult for the participant to withhold personal and health-related information which they did not wish to share with the employer.

Discussion

Our review concludes that interventions involving the workplace could potentially increase the probability of returning to work. The studies on IPS with the workplace involved had a very low certainty of evidence, making it impossible to assess the impact of these interventions. A very low certainty of evidence, however, does not necessarily mean that there is no effect: it highlights the need for more well-designed studies of this topic. Studies of behavioural therapy and team-based support yielded low certainty of evidence, which implies that it is possible that future research might change these results.

Our results are largely consistent with previous systematic reviews targeting people with CMDs (Finnes et al. 2019a; Joyce et al. 2016; Nigatu et al. 2016), mental health conditions (Fadyl et al. 2020), mental disorders (Dewa et al. 2015), depression (Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2020) or adjustment disorders (Arends et al. 2012): there is no convincing evidence that the interventions involving the workplace led to return to. As in our review, previous systematic reviews have included a range of interventions (e.g., targeting the individual’s workability, RTW behaviour, coping strategies, problem-solving skills, and interpersonal behaviours or organizational change). Besides the variety across the interventions, these are based on different mechanisms. As suggested by Nieuwenhuijsen and colleagues (Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2020) the mechanisms could be broadly classified into (a) improving working conditions for supporting the employee to overcome the barriers for returning to work, e.g., by the adjustment of working hours or work tasks, or (b) the improvement of depressive or other psychological symptoms using medication and/or therapy (e.g., CBT) (Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2020). In our systematic review, the included interventions were grouped into three categories. In addition, the interventions included in the categories ‘IPS’ and ‘Work-focused team-base support’ were mainly based on the first mechanism, while the interventions in the category ‘Work-focused behavioural therapy’ utilized a combination (Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2020). However, irrespective of clarity of mechanisms, we cannot draw any firm conclusions regarding the interventions’ effectiveness. Another problem in the categorization of interventions is the potential overlap between the interventions. Our categorization was based on the main content of each intervention. However, in the study by (Reme et al. 2015) an intervention with CBT and individual support based on IPS-principles was evaluated. All participants in the intervention group received up to 15 CBT sessions, and of those, 32% received individual support based on IPS-principles. We have based our categorization on the fact that CBT was delivered to all study participants in the intervention group and a lesser amount receiving individual support. Still, with the range of intervention and the need of exploring why an intervention results in the desired effect or not, we suggest a thorough examination of the adherence to an intervention’s components by e.g., evaluating the reach, dose delivered, received and underlying mechanisms. This could be done by conducting a process evaluation in parallel to an effectiveness trial. A process evaluation could add to the current knowledgebase by informing results from a randomized controlled trial with how much of each component that needs to be delivered, the uptake of the intervention and components and the users’ perceptions about barriers to, and facilitators of the intervention. Having the work-directed intervention in mind, i.e., a complex intervention commonly delivered and evaluated at individual, organizational societal levels (Skivington et al. 2021) a process evaluation could develop the interpretation of the results from an effectiveness trial. For example, Arends and colleagues’ (Arends et al. 2012) reported that several of the intervention’s components (e.g., inventory of problems and/or opportunities and support needed) were linked to the outcome recurrent sickness absence. Hence, their process evaluation provided an example of how a thorough examination of an intervention’s components explain the intervention’s effectiveness.

Even if our systematic review did not include studies with a qualitative design, the addition of study participants’ perspective of the interventions could provide sufficient knowledge to our findings. Previous studies reporting the individuals’ experiences of participating in work-directed intervention have shown that the individual’s learned from receiving individual support in their preparation of RTW. The intervention by Wisenthal and colleagues contained a mapping of work ability, need and motivation for RTW, which contributed to the participants’ self-reflection, visualizing their resources and clarifying demands (Wisenthal et al. 2019). Further, the professionals providing work-directed interventions needed an including attitude regarding the individual’s situation and experiences in combination with their medical expertise (Andersen et al. 2014; Strömbäck et al. 2020). However, besides the support needed when preparing the RTW, support is also needed during the RTW to achieve a seamless transition from sickness absence into re-entering work (Wästberg et al. 2013). Among non-employed individuals with long-term conditions, support is needed throughout the process of gaining a paid employment, e.g., by sufficient collaboration with the involved stakeholders (Fadyl et al. 2022). These findings add to the results of our systematic review by, on the one hand, using interventions which support the development of self-efficacy and motivation. On the other hand, the participants asked for more ‘hands on-support’ during and after they had returned to work. We conclude that the interventions included in our systematic review could benefit from being adjusted to individual needs of behavioural change and support.

In addition to previous systematic reviews, our review highlights several ethical aspects arising from work-directed interventions. The included interventions suggest increased cooperation between stakeholders, e.g., the individual on sickness absence, his/her employer, health care- and Social Insurance Agency’s representatives. Our ethical analysis indicates that the explored interventions may affect the individual’s autonomy, personal integrity and control over the sharing of sensitive information. These results are in line with Holmlund et al. (Holmlund et al. 2023). In addition, Holmlund and colleagues revealed that unclear roles among the professionals involved in delivering work-directed interventions implied unequal access to support (Holmlund et al. 2023). Another ethical analysis of a similar intervention showed ethical challenges due to conflicting goals on organizational and individual levels, e.g., the intervention challenged organizational values on fairness and justice, and introduced a need for the individual to juggle the roles of an employee and a patient (Karlsson et al. 2024). The interventions investigated in our systematic review presume a common goal of reintegrating the employee back to work, among the involved stakeholders. However, our results show that work-directed interventions come with ethical ‘costs’ on behalf of (first, and foremost) the individual, but—as shown by previous studies (Holmlund et al. 2023; Karlsson et al. 2024) on the behalf of the involved stakeholders and organizations. Given the inconclusive results shown by our, and previous systematic reviews of work-directed interventions, the results from our ethical analysis should be taken into consideration when planning and conducting work-directed interventions. Further, these results might guide policy- and decisionmakers whether to implement work-directed interventions.

Allowing for quasi-experimental designs in systematic reviews of effectiveness

Despite our search of quasi-experimental designs, we did not find any studies which met the inclusion criteria. Although quasi-experimental studies examining RTW outcomes for sick leave individuals exist, they encompass broader diagnostic populations beyond Common Mental Disorders (CMD), thus being excluded from our review. For instance, Hägglund et al. (Hägglund et al. 2020) analysed the impact of CBT on individuals with mild or moderate mental illness, and Hägglund (Hägglund 2013) assessed the effects of stricter enforcement of eligibility criteria in the Swedish sickness insurance system. These studies belong primarily to the field of economics, highlighting a discrepancy in population focus across research disciplines.

However, we suggest future systematic reviews to allow the inclusion of quasi-experimental designs when evaluating an intervention’s effectiveness, as these may often be considered to have a high external validity. Quasi-experimental designs offer a valuable alternative when ethical or logistical considerations prevent the implementation of true experiments. While randomised control trials aim to establish causal effects through random assignment, quasi-experimental designs achieve a similar goal without relying on true randomization. Instead, subjects are grouped based on predetermined criteria, mirroring random assignment to mitigate individual selection biases common in non-randomized experiments. Key quasi-experimental methods include Regression Discontinuity, Differences-in-Differences, and the Instrumental Variable method, as detailed, for instance, by Angrist and Pischke (Angrist and Pischke 2009).

Further, quasi-experiments often present several advantages. These include typically larger sample sizes, a reduced risk of biased population sampling, and the absence of issues related to participants and/or caseworkers being aware that they are part of a study. Quasi-experiments may have these advantages because they involve real-world interventions that have already been implemented without the explicit purpose of evaluation. Consequently, the concern that participants are aware of being part of a study is not an issue. Moreover, their use of retrospective register data helps alleviate problems associated with small sample sizes and attrition.

Quasi-experiments also have shortcomings, particularly if the fundamental assumption for identifying a causal treatment effect is unlikely to be met. Comparing the advantages and disadvantages of experiments versus quasi-experiments is not straightforward, as it hinges on the quality and context of the specific study. Our rationale for including quasi-experimental studies in the review lies in their potential to furnish evidence as compelling as RCT studies, underscoring their significance in systematic reviews.

Exploiting the potential of quasi-experiments to study subpopulations of interest, such as CMD, within larger sample sizes could contribute to improving research quality. Furthermore, quasi-experimental methods can be utilized for evaluating existing interventions and can be implemented gradually in different regions to leverage temporal variations for evaluation purposes. It is of interest to note that there are also RCT studies conducted in economics that evaluate labor market interventions but also include broader populations than those with CMD, such as the studies by Fogelgren et al. (Fogelgren et al. 2023), Engström et al. (Engström et al. 2017) and Laun and Skogman Thoursie (Laun and Skogman Thoursie 2014).

More studies of high scientific quality are needed

A recurring conclusion from the previous reviews is that more studies of high scientific quality are needed. We agree with this conclusion. About half the studies meeting our inclusion criteria were excluded from the review because they were assessed as having a high risk of bias. We have identified the following methodological aspects for consideration in future research.

Firstly, a recurrent problem is the small number of participants and underpowered trials. Experiments are resource-intensive, and the cost of large-scale experiments is significant. This means that RCT studies often become small-scale. Most studies included in our review report recruitment difficulties, which implies a risk that the pre-estimated group size cannot be achieved. In addition, many studies are conducted at a few local offices or centres where the participants are not necessarily representative of a broader population. These aspects reduce the external validity.

Secondly, it is difficult to withhold information that the participants are part of a study. Consent from participants is usually required and neither the participants nor those providing the interventions are blinded. While initially it may be feasible to withhold information regarding the assigned intervention from individuals, it is important to consider that the intervention unfolds over a specific duration, and participants can hardly be shielded from external information indefinitely. These aspects reduce the internal validity.

Thirdly, the studies lack detailed descriptions of the content of interventions, comparisons groups and so-called ‘co-interventions’. With reference to ‘care as usual’ only two studies reported the use of drug treatment (Dalgaard et al. 2017a, 2017b; Salomonsson et al. 2017, 2020). Such treatment is commonly used for reducing symptoms of e.g., anxiety and/or depression and could possibly influence the outcome of sickness absence. The absence of such information makes it difficult to interpret the results of the studies and limits the ability to replicate them.

Fourthly, in line with recent research findings, we support the necessity to establish standardized outcome measures, a ‘Core Outcome Set’ (see Hoving et al. 2018; Ravinskaya et al. 2023; Ravinskaya et al. 2022). The main argument is to be able to compare studies. For example, while some studies focus on the duration until return to work, others emphasize the share of individuals who have returned to work, or the duration of sick leave. Nonetheless, our study reveals additional crucial insights regarding a ‘Core Outcome Set’. First, it is important to have a common approach how to calculate outcomes. Even if the same outcome information is available, some authors favour odds ratios, while others prefer alternative measure such as the share returned to work. Secondly, we emphasize the merits of utilizing core outcomes derived from register data. We argued for the inclusion of quasi-experimental studies in our report, where register data is essential. Once again, the establishment of a ‘Core Outcome Set’ is paramount. The question is if this core set of outcomes can also include registry-based measures of health. This could involve, for example, the number of days in outpatient care, inpatient care, and the number of prescribed doses of medication.

Finally, our systematic review evaluated three distinct interventions, IPS and ‘Work-focused’ team-base support and ‘Work-focused’ CBT. As already argued, to explore why an intervention results in the desired effect or not, we advocate process evaluations in order to learn the underlying mechanisms for the potential success of an interventions. This also opens up the question whether an intervention could be more successful if it, for example, incorporated elements from both IPS and CBT. This suggest that studies do not only randomize individuals to singular treatment arms, such as IPS or CBT, but also to a combined treatment arm, such as IPS and CBT together.

Methodological considerations

One strength of our study is the comprehensive literature search in international databases, citation searches, and different publication types, including ‘grey literature’. The risk of overlooking any significant studies is small. Further, the certainty of the quantitative results has been assessed by applying the international GRADE system, which means that a structured assessment was made of five domains.

With regard to limitations, our review included articles reporting RCTs conducted in Sweden, Denmark, Norway and The Netherlands. These countries have different social insurance systems which could potentially affect the outcome, and this should therefore be considered when interpreting the results. Another limitation is our categorization of the included interventions. Even if an intervention had a specific content, e.g., CBT, it was not possible to determine whether the content was the same across studies, not whether the competence and training of those implementing the intervention affected the outcome.

References

Andersen MF, Nielsen K, Brinkmann S (2014) How do workers with common mental disorders experience a multidisciplinary return-to-work intervention? A Qualitative Study J Occup Rehabil 24(4):709–724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9498-5

Angrist JD, Pischke J-S (2009) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Arends I et al (2012) Interventions to facilitate return to work in adults with adjustment disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12:CD006389. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006389.pub2

Balshem H et al (2011) GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 64(4):401–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015

Bejerholm U, Larsson ME, Johanson S (2017) Supported employment adapted for people with affective disorders—a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord 207:212–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.028

Bryan ML, Bryce AM, Roberts J (2021) The effect of mental and physical health problems on sickness absence. Eur J Health Econ 22(9):1519–1533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-021-01379-w

Carroll C, Rick J, Pilgrim H, Cameron J, Hillage J (2010) Workplace involvement improves return to work rates among employees with back pain on long-term sick leave: a systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions. Disabil Rehabil 32(8):607–621. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638280903186301

Dalgaard VL, Andersen LPS, Andersen JH, Willert MV, Carstensen O, Glasscock DJ (2017a) Work-focused cognitive behavioral intervention for psychological complaints in patients on sick leave due to work-related stress: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Negat Results Biomed 16(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12952-017-0078-z

Dalgaard VL et al (2017b) Return to work after work-related stress: a randomized controlled trial of a work-focused cognitive behavioral intervention. Scand J Work Environ Health 43(5):436–446. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3655

Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Joosen MCW (2015) The effectiveness of return-to-work interventions that incorporate work-focused problem-solving skills for workers with sickness absences related to mental disorders: a systematic literature review. BMJ Open 5(6):e007122. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007122

Engström P, Hägglund P, Johansson P (2017) Early interventions and disability insurance: experience from a field experiment. Econ J (london) 127(600):363–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12310

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) Psychosocial risks and stress at work. In. https://osha.europa.eu/en/themes/psychosocial-risks-and-stress

Fadyl JK, Anstiss D, Reed K, Khoronzhevych M, Levack WMM (2020) Effectiveness of vocational interventions for gaining paid work for people living with mild to moderate mental health conditions: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 10(10):e039699. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039699

Fadyl JK, Anstiss D, Reed K, Levack WMM (2022) Living with a long-term health condition and seeking paid work: qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. Disabil Rehabil 44(11):2186–2196. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1826585

Finnes A, Enebrink P, Ghaderi A, Dahl J, Nager A, Öst LG (2019a) Psychological treatments for return to work in individuals on sickness absence due to common mental disorders or musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 92(3):273–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-018-1380-x

Finnes A, Ghaderi A, Dahl J, Nager A, Enebrink P (2019b) Randomized controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and a workplace intervention for sickness absence due to mental disorders. J Occup Health Psychol 24(1):198–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000097

Fisker J, Hjorthøj C, Hellström L, Mundy SS, Rosenberg NG, Eplov LF (2022) Predictors of return to work for people on sick leave with common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 95(7):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01827-3

Fogelgren M, Ornstein P, Rödin M, Skogman Thoursie P (2023) Is supported employment effective for young adults with disability pension? J Hum Resour 58(2):452. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.58.4.0319-10105R2

Hellström L, Bech P, Hjorthoj C, Nordentoft M, Lindschou J, Eplov LF (2017) Effect on return to work or education of individual placement and support modified for people with mood and anxiety disorders: results of a randomised clinical trial. Occup Environ Med 74(10):717–725. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2016-104248

Hoff A et al (2022) Integrating vocational rehabilitation and mental healthcare to improve the return-to-work process for people on sick leave with depression or anxiety: results from a three-arm, parallel randomised trial. Occup Environ Med 79(2):134–142. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2021-107894

Hogg B et al (2021) Workplace interventions to reduce depression and anxiety in small and medium-sized enterprises: A systematic review. J Affect Disord 290:378–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.071

Holmlund L, Sandman L, Hellman T, Kwak L, Björk Brämberg E (2023) Ethical aspects of the coordination of return-to-work among employees on sick leave due to common mental disorders: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil 45(13):2118–2127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2084779

Hoving J, Prinsen C, Kunz R, Verbeek J (2018) Need for a core outcome set on work participation. TBV—Tijdschrift Voor Bedrijfs- En Verzekeringsgeneeskunde 26(7):362–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12498-018-0236-3

Hägglund P (2013) Do time limits in the sickness insurance system increase return to work? Empir Econ 45(1):567–582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-012-0618-9

Hägglund P, Johansson P, Laun L (2020) The impact of CBT on sick leave and health. Eval Rev 44(2–3):185–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841x20976516

Joyce S et al (2016) Workplace interventions for common mental disorders: a systematic meta-review. Psychol Med 46(4):683–697. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002408

Karlsson I, Sandman L, Axén I, Kwak L, Sernbo E, Björk Brämberg E (2024) Ethical challenges from a problem-solving intervention with workplace involvement: a qualitative study among employees with common mental disorders, first-line managers, and rehabilitation coordinators. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being 19(1):2308674. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2024.2308674

Lammerts L, Schaafsma FG, Bonefaas-Groenewoud K, van Mechelen W, Anema J (2016) Effectiveness of a return-to-work program for workers without an employment contract, sick-listed due to common mental disorders. Scand J Work Environ Health 42(6):469–480. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3588

Lammerts L, van Dongen JM, Schaafsma FG, van Mechelen W, Anema JR (2016) A participatory supportive return to work program for workers without an employment contract, sick-listed due to a common mental disorder: an economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 17(1):162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4079-0

Laun L, Skogman Thoursie P (2014) Does privatisation of vocational rehabilitation improve labour market opportunities? evidence from a field experiment in Sweden. J Health Econ 34:59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.12.002

Marmot M (2017) Social justice, epidemiology and health inequalities. Eur J Epidemiol 32(7):537–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0286-3

Mikkelsen MB, Rosholm M (2018) Systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions aimed at enhancing return to work for sick-listed workers with common mental disorders, stress-related disorders, somatoform disorders and personality disorders. Occup Environ Med 75(9):675–686. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2018-105073

Modini M et al (2016) The mental health benefits of employment: results of a systematic meta-review. Australas Psychiatry 24(4):331–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856215618523

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Verbeek JH, Neumeyer-Gromen A, Verhoeven AC, Bultmann U, Faber B (2020) Interventions to improve return to work in depressed people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10(10):CD006237. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006237.pub4

Nigatu YT et al (2016) Interventions for enhancing return to work in individuals with a common mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychol Med 46(16):3263–3274. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291716002269

OECD (2021) Fitter Minds, Fitter Jobs: From Awareness to Change in Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policies, Mental Health and Work. In. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/a0815d0f-en

Overland S, Grasdal AL, Reme SE (2018) Long-term effects on income and sickness benefits after work-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy and individual job support: a pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med 75(10):703–708. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2018-105137

Page MJ et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Ravinskaya M et al (2023) Which outcomes should always be measured in intervention studies for improving work participation for people with a health problem? an international multistakeholder Delphi study to develop a core outcome set for work participation (COS for work). BMJ Open 13(2):e069174. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069174

Ravinskaya M et al (2022) A general framework for selecting work participation outcomes in intervention studies among persons with health problems: a concept paper. BMC Public Health 22(1):2189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14564-0

Reme SE, Grasdal AL, Lovvik C, Lie SA, Overland S (2015) Work-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy and individual job support to increase work participation in common mental disorders: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Occup Environ Med 72(10):745–752. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2014-102700

Salomonsson S, Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Öst LG (2018) Sickness absence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological treatments for individuals on sick leave due to common mental disorders. Psychol Med 48(12):1954–1965. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291718000065

Salomonsson S et al (2017) Cognitive-behavioural therapy and return-to-work intervention for patients on sick leave due to common mental disorders: a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med 74(12):905–912. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2017-104342

Salomonsson S et al (2020) Effects of cognitive behavioural therapy and return-to-work intervention for patients on sick leave due to stress-related disorders: results from a randomized trial. Scand J Psychol 61(2):281–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12590

Schuring M, Robroek SJ, Burdorf A (2017) The benefits of paid employment among persons with common mental health problems: evidence for the selection and causation mechanism. Scand J Work Environ Health 43(6):540–549. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3675

Skivington K et al (2021) A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of medical research council guidance. BMJ 374:n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061

Sterne JAC et al (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

Strömbäck M, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Keisu S, Sturesson M, Eskilsson T (2020) Restoring confidence in return to work: A qualitative study of the experiences of persons with exhaustion disorder after a dialogue-based workplace intervention. PLoS ONE 15(7):e0234897. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234897

van der Noordt M, IJzelenberg H, Droomers M, Proper KI (2014) Health effects of employment: a systematic review of prospective studies. Occup Environ Med 71(10):730–736. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2013-101891

van Vilsteren M, van Oostrom SH, de Vet HC, Franche RL, Boot CR (2015) Anema JR (2015) Workplace interventions to prevent work disability in workers on sick leave. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10:Cd006955. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006955.pub3

Wisenthal A, Krupa T, Kirsh B, Lysaght R (2019) Insights into cognitive work hardening for return-to-work following depression: qualitative findings from an intervention study. Work (reading, Mass) 62(4):599–613. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-192893

Wästberg BA, Erlandsson LK, Eklund M (2013) Client perceptions of a work rehabilitation programme for women: the redesigning daily occupations (ReDO) project. Scand J Occup Ther 20(2):118–126. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2012.737367

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. The work was funded by the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (reference number SBU 2022/494). The funder has no involvement in the design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the results or writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the idea of the article, the study conception and design. The literature search was conducted by Carl Gornitzki, the data analysis and interpretation of data were conducted by all authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Elisabeth Björk Brämberg, Peter Skogman Thoursie and Elizabeth Åhsberg. Elisabeth Björk Brämberg drafted and revised the work based on all authors comments on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no competing interest.

Ethical approval

This study does not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brämberg, E., Åhsberg, E., Fahlström, G. et al. Effects of work-directed interventions on return-to-work in people on sick-leave for to common mental disorders—a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-024-02068-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-024-02068-w