Abstract

The 2010 eruption of Merapi (VEI 4) was the volcano’s largest since 1872. In contrast to the prolonged and effusive dome-forming eruptions typical of Merapi’s recent activity, the 2010 eruption began explosively, before a new dome was rapidly emplaced. This new dome was subsequently destroyed by explosions, generating pyroclastic density currents (PDCs), predominantly consisting of dark coloured, dense blocks of basaltic andesite dome lava. A shift towards open-vent conditions in the later stages of the eruption culminated in multiple explosions and the generation of PDCs with conspicuous grey scoria and white pumice clasts resulting from sub-plinian convective column collapse. This paper presents geochemical data for melt inclusions and their clinopyroxene hosts extracted from dense dome lava, grey scoria and white pumice generated during the peak of the 2010 eruption. These are compared with clinopyroxene-hosted melt inclusions from scoriaceous dome fragments from the prolonged dome-forming 2006 eruption, to elucidate any relationship between pre-eruptive degassing and crystallisation processes and eruptive style. Secondary ion mass spectrometry analysis of volatiles (H2O, CO2) and light lithophile elements (Li, B, Be) is augmented by electron microprobe analysis of major elements and volatiles (Cl, S, F) in melt inclusions and groundmass glass. Geobarometric analysis shows that the clinopyroxene phenocrysts crystallised at depths of up to 20 km, with the greatest calculated depths associated with phenocrysts from the white pumice. Based on their volatile contents, melt inclusions have re-equilibrated during shallower storage and/or ascent, at depths of ~0.6–9.7 km, where the Merapi magma system is interpreted to be highly interconnected and not formed of discrete magma reservoirs. Melt inclusions enriched in Li show uniform “buffered” Cl concentrations, indicating the presence of an exsolved brine phase. Boron-enriched inclusions also support the presence of a brine phase, which helped to stabilise B in the melt. Calculations based on S concentrations in melt inclusions and groundmass glass require a degassing melt volume of 0.36 km3 in order to produce the mass of SO2 emitted during the 2010 eruption. This volume is approximately an order of magnitude higher than the erupted magma (DRE) volume. The transition between the contrasting eruptive styles in 2010 and 2006 is linked to changes in magmatic flux and changes in degassing style, with the explosive activity in 2010 driven by an influx of deep magma, which overwhelmed the shallower magma system and ascended rapidly, accompanied by closed-system degassing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arc volcanoes may erupt explosively or effusively and transitions between eruptive styles are common. Transitions between effusive dome-forming and explosive (sub) plinian eruptions have been related to changes in various factors, including magma composition, volatile content, degassing regime, changes in magma supply, ascent rate and overpressure, as well as crystallisation during ascent (e.g. Jaupart and Allègre 1991; Woods and Koyaguchi 1994; Eichelberger 1995; Villemant and Boudon 1998; Martel et al. 1998; Melnik and Sparks 1999, 2005; Scandone et al. 2007; Ruprecht and Bachmann 2010). Deep magmatic influx into a reservoir has been identified as an eruption trigger in many previous studies (e.g. Murphy et al. 2000; Ridolfi et al. 2008; Suzuki et al. 2013). Magmatic influx may in turn affect magma ascent dynamics, influencing the rate of magma ascent and whether ascent is sustained or pulsatory in its nature (Wolf and Eichelberger 1997; Scandone et al. 2007). Previous studies have shown that the style of degassing (open vs. closed) is pivotal in determining eruptive behaviour. During open-system degassing, exsolved volatiles are separated and lost from the melt through various pathways such as through the vent and/or the conduit walls, leading to effusive eruptive activity (e.g. Eichelberger et al. 1986; Melnik and Sparks 1999; Villemant et al. 2008). In closed-system degassing, the exsolved volatiles remain within the system, tending to result in increased overpressure, vesicularity and capacity for explosive eruption (Wilson et al. 1980). During magma ascent, processes of degassing and crystallisation, and the consequent changes to magma rheology also influence eruptive style via complex feedback mechanisms (Sparks 1997; Melnik and Sparks 1999, 2005).

Silicate melt inclusions trapped in phenocrysts potentially retain evidence about the pre-eruptive magma that may not be preserved elsewhere, providing critical information about the processes operating during magmatic evolution. For example, melt inclusions can preserve the composition and dissolved volatile concentrations of a pre-eruptive melt, and have previously been used to shed light on minimum pressures of crystallisation and to supply information about exsolved fluids present during crystallisation [see Lowenstern (1995, 2003) and Kent (2008) for reviews of the subject]. However, the interpretation of melt inclusion volatile concentrations is challenging, both analytically and due to potential changes in the initial composition by formation of boundary layer conditions (e.g. Baker 2008) or by post-entrapment processes, including crystallisation and diffusive loss through the crystal lattice or cracks (e.g. Lowenstern 1995).

At Merapi, previous volcanological and petrological work suggests that the eruptive style of past dome-forming and larger sub-plinian eruptions has been governed by slow versus fast magma ascent rate and open- versus closed-system degassing (Gertisser 2001; Gertisser et al. 2011) and that shallow-level dynamics control the eruptive behaviour (Gauthier and Condomines 1999). In addition, crustal carbonate assimilation and the resulting CO2 liberation has also been invoked to play a significant role in governing the explosivity of eruptions (Chadwick et al. 2007; Deegan et al. 2010; Troll et al. 2012, 2013; Borisova et al. 2013). Secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) volatile data (CO2, H2O, F, Cl, S) of Merapi clinopyroxene and amphibole-hosted silicate melt inclusions in lava and scoria from unknown eruptive origins have recently been published by Nadeau et al. (2013). The authors suggest that CO2, liberated by crustal carbonate assimilation fluxed the melt, thereby promoting CO2 enrichment of the melt and H2O degassing. In addition, the magmatic volatile phase exsolved into a H2O–Cl–F-rich brine and CO2–S-rich vapour.

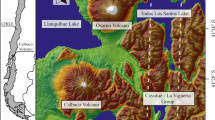

Focussing on the cataclysmic eruption of Merapi in 2010 and the previous eruption in 2006, this paper presents the hitherto most comprehensive set of melt inclusion data, including the first SIMS data for the 2006 and 2010 eruption products. Comparing data between these eruptions is crucial to understand the recent pre-eruptive magmatic system of Merapi. Data include measurements of volatiles (H2O, CO2, Cl, S, F), light lithophile trace elements (B, Li, Be) and major element concentrations in a comprehensive suite of clinopyroxene-hosted melt inclusions, gathered from stratigraphically controlled samples of various stages of the 2010 Merapi eruption. These include dense dome clasts, as well as grey scoria and white pumice, from the subsequent sub-plinian stage (Fig. 1). These data are complemented by analysis of the host clinopyroxene phenocrysts as well as groundmass glass. The diverse and stratigraphically controlled sample set, produced by rapidly changing eruptive behaviour in 2010, is used to shed light on the magmatic contribution to the shifts in eruptive style during a single eruptive period at Merapi. In addition, comparison of the various 2010 samples to those originating from scoriaceous dome fragments produced during the peak of the dome-forming 2006 eruption, elucidates pre-eruptive processes during the two most recent and contrasting eruptions of Merapi. Results of this work are beneficial for hazard analysis at Merapi and possibly other dome-forming volcanoes worldwide, providing insights into factors contributing to changes in eruptive behaviour, which, as the 2010 eruption of Merapi demonstrated, may occur rapidly and with few imminent warning signs.

Eruptive timeline of the 2010 eruption, with stages based on Komorowski et al. (2013) and expanded section describing the paroxysmal eruptive activity of 5 November 2010 and samples used in this paper. Deposit map showing the extent of deposits emplaced on 26 October 2010, as well as during Stage 4 and Stage 6 (modified after Komorowski et al. 2013)

Background

Merapi magmatic system and volatiles

The plumbing system of Merapi is thought to consist of multiple magma storage and crystallisation regions, ranging over almost the entire thickness of the crust (e.g. Beauducel and Cornet 1999; Ratdomopurbo and Poupinet 2000; Gertisser 2001; Chadwick et al. 2007, 2013; Costa et al. 2013). Evidence for this comes from both petrological and geophysical studies. Geobarometry of magmatic inclusions indicates that crystallisation at Merapi occurs over a wide range of depths (~2–45 km), with the majority occurring at mid- to lower-crustal levels (12–18 km) (Chadwick et al. 2013). Mineral equilibria in lavas and pyroclastic rocks also reveal a major magma storage region at mid- to lower-crustal levels (14–19 km) (Gertisser 2001), corroborated by estimates of amphibole crystallisation depths (Preece et al. 2011; Nadeau et al. 2013). Petrological data, which elucidate the magma storage conditions prior to the 2006 and 2010 eruptions, demonstrate that there were multiple zones of crystallisation at depths throughout the crust prior to both eruptions (Costa et al. 2013; Preece et al. 2013; Troll et al. 2013; Preece 2014). Geophysical data also suggest the presence of multiple magma storage regions at Merapi. Tilt and GPS data indicate an average source depth for magma storage at 8.5 ± 0.4 km below the summit (Beauducel and Cornet 1999), broadly consistent with the depth of an aseismic zone observed at >5 km below the summit, thought to represent the presence of melt (Ratdomopurbo and Poupinet 2000). In addition, an aseismic zone located at 1.5–2.5 km depth below the summit is interpreted to be a shallow ephemeral storage region, where magma is temporarily stored as it migrates from the deeper reservoir(s) before eruption (Ratdomopurbo and Poupinet 2000). Shallow storage regions have also been proposed based upon Bouguer gravity anomaly data (Saepuloh et al. 2010). The volume of this shallow magma storage region has been estimated at ~1.6–1.7 × 107 m3 based upon (210Pb) in Merapi fumarolic gas and magma residence times as determined from (210Pb/226Ra) disequilibria (Gauthier and Condomines 1999; Le Cloarec and Gauthier 2003). Gas emissions at Merapi are H2O-rich (~84–95 mol%), with lesser amounts of CO2 (<10 mol%) and minor amounts of SO2 and H2S (Le Guern et al. 1982; Zimmer and Erzinger 2003). Previous work has concluded that effusive volcanism at Merapi is accompanied by open-system degassing, with most of the degassing occurring within the conduit during ascent or during magma residence in a shallow magma chamber below the summit (Le Pennec et al. 2001; Le Cloarec and Gauthier 2003). Evidence of a deeper gas and magma supply to this shallower system has been reported, with inputs of deep, undegassed magma into the shallower, degassing reservoir (Gauthier and Condomines 1999; Le Cloarec and Gauthier 2003; Costa et al. 2013). For example, volcanic gases are enriched in S compared to modelled volatile phases, attributed to a deeper, reduced, mafic magma supplying S to the shallow magmatic system (Nadeau et al. 2010, 2013). It is estimated that the magma degassing rate is 40 times greater than the lava extrusion rate of the past 100 years would suggest (Allard et al. 2011). This suggests that the magma storage region is large enough to accommodate substantial amounts of unerupted, degassing magma, with continuous gas percolation through the magma system (Allard et al. 2011). At Merapi, CO2 is thought to originate both from a mantle source and from crustal carbonate assimilation. Isotopic data indicate a mantle-derived origin for most volatiles at Merapi, with additional CO2 derived from crustal contamination (Allard et al. 2011). The upper crustal rocks around Merapi are comprised of a ~10-km-thick sequence of Cretaceous to Tertiary limestones, marls and volcaniclastic rocks (van Bemmelen 1949; Hamilton 1979; Smyth et al. 2005). Calc-silicate xenoliths are commonly found within Merapi lavas, providing evidence for the interaction of magma with crustal carbonate material (e.g. Clocchiatti et al. 1982; Camus et al. 2000; Gertisser and Keller 2003; Chadwick et al. 2007; Deegan et al. 2010; Troll et al. 2012, 2013). Magma–carbonate interaction liberates CO2 through decarbonation reactions of crustal carbonates to the diopside and wollastonite assemblages observed in the xenoliths, adding to the magmatic volatile budget with the potential to sustain and intensify eruptions at Merapi (Deegan et al. 2010; Troll et al. 2012, 2013).

The 2010 and 2006 eruptions of Merapi

In 2010, Merapi volcano had its largest eruption (VEI 4) since 1872 (e.g. Surono et al. 2012). In contrast to recent prolonged and effusive dome-forming eruptions at Merapi, such as the previous eruption in 2006 (Charbonnier and Gertisser 2008; Preece et al. 2013; Ratdomopurbo et al. 2013), the 2010 eruption began explosively and a new lava dome grew in the newly formed crater prior to explosive destruction of this dome during the peak of the eruption on 5 November 2010, followed by further explosive activity and extrusion of a new dome after 5 November (Surono et al. 2012; Komorowski et al. 2013; Pallister et al. 2013) (Fig. 1). The 2010 eruption chronology and deposits have previously been documented in detail (e.g. Surono et al. 2012; Pallister et al. 2013; Charbonnier et al. 2013; Komorowski et al. 2013). Komorowski et al. (2013) recognised eight stages of the 2010 eruption, which will be referred to throughout this paper (Fig. 1): Stage 1: unrest and magmatic intrusion (31 October 2009–26 October 2010); Stage 2: initial explosions (26 October 2010); Stage 3: recurrent rapid dome growth and destruction (29 October–4 November 2010); Stage 4: paroxysmal dome explosions and collapse (5 November 2010); Stage 5: retrogressive summit collapse (5 November); Stage 6: sub-plinian fountain collapse (5 November 2010); Stage 7: rapid dome growth with alternating effusive and explosive activity (5–8 November 2010); Stage 8: declining ash venting and degassing (8–23 November 2010).

In contrast to 2010, previous episodes of volcanic activity at Merapi over the last century were frequently characterised by prolonged dome extrusion and subsequent gravitational collapse to produce block-and-ash flows (BAFs) or “Merapi-type nuées ardentes” (e.g. Andreastuti et al. 2000; Newhall et al. 2000; Voight et al. 2000; Gertisser et al. 2012a; Surono et al. 2012). The previous eruption in 2006 is a well-characterised extrusive, dome-forming eruption at Merapi (Charbonnier and Gertisser 2008; Gertisser et al. 2012b; Preece et al. 2013; Ratdomopurbo et al. 2013). Although the 2006 eruption displayed typical Merapi dome-forming activity, peak dome extrusion rates reached 3.3 m3 s−1 (Ratdomopurbo et al. 2013), which is high compared to other recent Merapi eruptions. For example, it is an order of magnitude higher than peak dome extrusion rates in 1994 (0.32 m3 s−1) (Ratdomopurbo 1995; Hammer et al. 2000). Throughout the >3 month long eruption, BAFs were generated by almost daily gravitational dome collapse. The peak of activity on 14 June 2006 consisted of multiple phases of dome collapse (Charbonnier and Gertisser 2008; Lube et al. 2011; Gertisser et al. 2012b) producing BAFs that travelled up to 7 km from the summit (Charbonnier and Gertisser 2008).

Methodology

Samples and sample preparation

Various samples from the different stages of the 2010 eruption were analysed, in particular, samples of dense dome material emplaced on 5 November (Stage 4 of Komorowski et al. 2013), as well as grey scoria and white pumice clasts from PDC deposits emplaced by subsequent convective fountain collapse (Stage 6 of Komorowski et al. 2013). Clinopyroxene-hosted silicate melt inclusions were analysed in all samples, and groundmass glass was analysed in all but the dense dome samples, as the groundmass was too crystalline to allow for accurate glass analysis. For comparison, clinopyroxene-hosted melt inclusions and groundmass glass were also analysed from scoriaceous dome fragments from the block-and-ash flows emplaced at the peak of the 2006 eruption on 14 June 2006 (Lobe 1 of Charbonnier and Gertisser 2008; Preece et al. 2013).

Grain mounts were prepared by crushing rock samples for a few seconds in an agate mill, before sieving to different size fractions to separate larger pyroxene phenocrysts. Several hundred clinopyroxene crystals were picked by hand under a binocular microscope from >1-mm and >500-μm-sieve fractions and mounted into low-volatility Struers EpoFix epoxy resin. Each grain mount was polished by hand with aluminium polishing solution down to 0.3 μm, until melt inclusions were exposed. Aluminium solution was used for polishing in order to avoid carbon and boron contamination, which may occur with diamond solutions. Inclusions were only studied after polishing, with the proviso that some petrographic information may have been lost during polishing. However, this method has the advantage that many melt inclusions can be analysed quickly, giving an extensive overview of the melt inclusion population (cf. Humphreys et al. 2008).

Analytical methods

Melt inclusions in gold-coated samples were analysed by secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) for isotopes of volatiles (1H+ and 12C+) and of light lithophile elements (7Li+, 9Be+, 11B+) using the Cameca ims-4f ion microprobe at the NERC Ion Microprobe Facility at the University of Edinburgh (UK). A subset of these inclusions were subsequently analysed for 12C+ at high resolution in order to minimise the interference of 24Mg2+ on 12C+. All 2010 and 2006 CO2 data in this paper are based on the high-resolution 12C+ results. Analyses were performed using a primary 16O− beam and positive secondary ion beam with an accelerating voltage of 4.5 kV. Energy filtering with a 75 ± 20 V offset, or a 50 V offset for high-resolution 12C+ measurements, was used with the purpose of minimising the transmission of unwanted molecular species. Surface contamination was eliminated by performing a 50-μm-diameter, 10 nA raster of the sample surface for 3 min prior to analysis. Results are based on the last 10 cycles, with the first 5 disregarded, or, for high-resolution 12C+ measurements, based on the last 8 with the first 4 disregarded, in order to abate effects of potential surface contamination and allow time for beam stabilisation. For all analyses, 30Si+ was used as an internal standard and corrected with SiO2 contents as measured by electron microprobe analysis. H2O and CO2 were measured using 1H+ and 12C+, respectively, calibrated using dacitic to rhyolitic glass standards with known H2O (up to 4.32 wt%) and CO2 (up to 10,380 ppm) concentrations and using working curves as described in Blundy and Cashman (2008). Standards that were used include the following experimental glasses: Sisson 51, Sisson 56, Sisson 59, RB480, Lipari, STHS, BF147 and MC84r. CO2 backgrounds were measured to be <5 ppm using CO2-free standards. Detection limits were typically ~10 ppm for CO2 and ~100 ppm for H2O. Analytical uncertainties based on measurements of the glass standards are <10 % (relative) for H2O and ~10–15 % (relative) for CO2.

Selected melt inclusions in the same polished epoxy grain mounts were also analysed for H2O and CO2 using attenuated total reflectance micro-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR micro-FTIR) at the USGS, Menlo Park, California. A Ge accessory crystal was used to measure evanescent wave absorption at 3,450 cm−1 (representing total H2O), at 2,350 cm−1 (representing molecular CO2) and at 1,400–1,500 cm−1 (representing carbonate) using the methods of Lowenstern and Pitcher (2013).

Each studied melt inclusion and host crystal was viewed with the SEM and analysed by electron probe only after the SIMS analysis in order to avoid possible contamination of C with the carbon coating. Major elements as well as Cl, F and S in the melt inclusions and groundmass glass were measured using Cameca SX100 electron microprobes at The Open University and the University of Cambridge. Glass was analysed using a defocussed beam diameter of 5–10 μm, an accelerating voltage of 15–20 kV and a 4–20 nA beam current for major elements and a 10–20 nA beam current for volatiles. Volatiles were analysed with extended peak counting times. Na was always measured first to minimise migration effects, and in-house natural mineral standards were used for calibration. Major elements were measured in the clinopyroxene host crystals, near to the site of each melt inclusion, as well as in other clinopyroxene phenocrysts in 2010 and 2006 samples. Although there is little zonation in the analysed clinopyroxene phenocrysts, if zoning was present then pyroxene analyses were made in the same zones in which melt inclusions were situated. Pyroxenes were analysed using a 1–5 μm beam diameter, a 15–20 kV accelerating voltage and a 15–20 nA beam current. Detection limits were ~100–250 ppm for major elements, ~100 ppm for S and Cl, and ~200 ppm for F. Analytical uncertainties for major elements, based on repeat analyses of natural mineral and rhyolitic glass standards, were in the order of 1–3 % (relative). Uncertainties of volatile element determinations are estimated at <5 % (relative) for S and Cl, and <15 % (relative) for F.

Back-scattered electron (BSE) images of all melt inclusions were acquired with a JEOL JSM 5900 LV SEM at the University of East Anglia, using an accelerating voltage of 20 kV and a working distance of 9 mm. All host crystals were imaged using an accelerating voltage of 20 kV and a working distance of 31–37 mm. Back-scattered electron images were then analysed in order to disregard analyses that were on cracks or occasional inclusions which contained any daughter crystals.

Whole-rock compositions were obtained from interior portions of fresh samples, which were washed in Milli-Q in a sonic bath for 15 min, dried overnight at >100 °C and powdered in a tungsten carbide mill. Major elements were analysed by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) using a Bruker AXS S4 Pioneer at the University of East Anglia. Loss on ignition (LOI) was carried out by heating in a furnace at 1,050 °C for 4 h.

All melt inclusion major element data were corrected for the compositional effects of post-entrapment crystallisation (PEC) of clinopyroxene at the melt inclusion–host interface. The corrections were performed by first calculating the composition of the host clinopyroxene that should be in equilibrium with the melt inclusion using an appropriate clinopyroxene-melt equilibrium model (Nielsen and Drake 1979). The equilibrium clinopyroxene was then added in 0.1 wt% increments to the measured melt inclusion composition until the equilibrium clinopyroxene composition becomes identical to that of the host, using the reverse fractional crystallisation modelling function of the Petrolog3 software (Danyushevsky and Plechov 2011). The calculated degree of PEC is <10 % but typically <5 %.

Results

Major element geochemistry

Major element compositional variations in whole rocks, melt inclusions and groundmass glass from 2010 and 2006 samples are shown in Fig. 2. Whole-rock compositions of both the 2010 and 2006 eruptive products are high-K basaltic andesite and show a similar compositional range (Preece et al. 2013; Preece 2014). SiO2 concentrations are between 54.1 and 55.7 wt% for 2010 juvenile samples and between 55.2 and 56.1 wt% for the 2006 products. A comparison of different 2010 lithologies reveals that the compositional range of the dense dome material erupted on 5 November extends to slightly less evolved compositions (54.1–55.6 wt% SiO2) than the white pumice (55.5–55.7 wt% SiO2) and the grey scoria (55.1–55.7 wt% SiO2), although the differences are marginal. There is a compositional gap of >5 wt% SiO2 between the most evolved whole-rock sample and the least evolved melt inclusion (Fig. 2). The melt inclusions are mainly dacitic to rhyolitic in composition, with 63.1–72.4 wt% SiO2, with only two classed as andesitic (61.7 and 62.3 wt% SiO2) when corrected for PEC and normalised to 100 % on a volatile-free basis (Table 1 and Electronic Supplementary Data). Both 2010 and 2006 melt inclusions cover a similar compositional range. Melt inclusions from each 2010 lithology generally span the entire observed compositional range, although the most evolved melt inclusions (>70 wt% SiO2) come exclusively from white pumice and grey scoria in the 2010 deposits. In comparison, 2006 clinopyroxene-hosted melt inclusions presented in Nadeau et al. (2013) have a more restricted compositional range between 64.2 and 69.8 wt% SiO2, and in addition, one amphibole-hosted inclusion is reported, which has 64.1 wt% SiO2. In 1998 dome samples, Schwarzkopf et al. (2001) reported plagioclase-hosted melt inclusions with 56.4–62.6 wt% SiO2 and Gertisser (2001) reported average values between 63.2 and 66.1 wt% SiO2 for melt inclusions in different samples of the Merapi high-K series rocks. Groundmass glass compositions represent the most evolved compositions (66.8–76.4 wt% SiO2). Overall trends of Al2O3, CaO, FeO* (total iron calculated as FeO) and MgO correlate negatively with SiO2, and K2O correlates positively with SiO2 (Fig. 2). Both TiO2 and Na2O trends are inflexed, with TiO2 concentrations decreasing until ~67 wt% SiO2 before groundmass TiO2 concentrations increase with increasing SiO2, and Na2O correlating positively until ~67 wt% SiO2, where Na2O concentrations begin to decrease.

Major element variation diagrams showing the composition of melt inclusions from 2010 dense dome material, white pumice and grey scoria, and 2006 scoriaceous dome clasts, as well as groundmass glass and whole-rock compositions from 2006 and 2010 samples. All melt inclusion compositions are corrected for PEC. All melt inclusion, groundmass glass and whole-rock measurements are normalised to 100 wt% on a volatile-free basis. FeO* = all iron reported as FeO

Volatile concentrations

H2O and CO2

SIMS analysis shows that the highest H2O concentrations occur in melt inclusions from the 2010 grey scoria (up to 3.94 wt%) and white pumice (up to 3.91 wt%) (Table 1). Melt inclusions from 2010 dense dome clasts are generally more degassed, although the highest measured H2O in the dome samples is 3.62 wt%. In comparison, melt inclusions from the scoriaceous 2006 dome fragments contain up to 3.73 wt% H2O (Table 1) [see Electronic Supplementary Data for full data set].

CO2 concentrations in melt inclusions are generally <200 ppm; although at high H2O concentrations, melt inclusions in the white pumice have increased CO2 concentrations up to 695 ppm. Several melt inclusions appear to have elevated CO2 concentrations (up to ~3,000 ppm) at medium (~2 wt%) H2O contents, a feature particularly associated with melt inclusions from the white pumice. The maximum CO2 measured in the 2010 grey scoria and dense dome melt inclusions is 146 ppm and 12 ppm, respectively, and in melt inclusions from the 2006 dome scoria, the maximum is 158 ppm CO2 (Table 1), although one inclusion is displaced towards higher CO2 concentrations (~2,400 ppm) at <1 wt% H2O.

A selected group of 2010 melt inclusions were also analysed for H2O and CO2 using ATR micro-FTIR. These inclusions were primarily targeted for ATR micro-FTIR analysis because results from the preceding SIMS analysis suggested that these inclusions were enriched in CO2 (up to ~3,000 ppm) at medium (~2 wt%) H2O contents, relative to the degassing trend displayed by other analysed inclusions (Fig. 3). ATR micro-FTIR results in this study reveal that although measured H2O concentrations are similar to the ones acquired by SIMS, the concentration of CO2 in the inclusions was below the detection limit (200 ppm).

Melt inclusion H2O and CO2 concentrations from SIMS analysis. a H2O versus CO2 measured with high-resolution SIMS. All measured melt inclusions including the “high-CO2” inclusions are shown, some of which were subsequently re-analysed with ATR micro-FTIR. As a comparison to the 2010 and 2006 melt inclusions, clinopyroxene-hosted melt inclusions from two older deposits are also shown, namely a young, widespread basaltic breadcrust bomb-rich PDC deposit on Merapi’s southern flank (Newhall et al. 2000; Gertisser et al. 2012a), tentatively ascribed to the VEI 4 1872 eruption, the last VEI 4 eruption prior to 2010 (Newhall et al. 2000), and the pumiceous “Trayem tephra” produced during a prehistoric VEI 4 sub-plinian eruption (Gertisser 2001; Gertisser et al. 2012a). Note that the breadcrust bomb and “Trayem tephra” CO2 values were obtained by low-resolution measurements. In addition, previously published data for amphibole phenocryst (Amph. ph.) amphibole megacryst (Amph. mgxt.) and clinopyroxene phenocryst (Cpx. ph.) hosted melt inclusions of unknown origins is also shown (Nadeau et al. 2013). b Enlarged view of measured melt inclusions excluding the “high-CO2” set. All isobars (fine solid lines) and vapour isopleths (fine dashed lines) calculated with VolatileCalc (Newman and Lowenstern 2002). Closed-system decompression degassing pathway (bold solid line) with 1 % exsolved vapour (bold solid line) starting at 1,000 ppm CO2 and 4.0 wt% H2O at 1,050 °C, and open-system degassing pathway starting at the same conditions (bold dashed line) calculated with VolatileCalc

Comparison of the melt inclusions analysed in this study with volatile data published by Nadeau et al. (2013) from melt inclusions in clinopyroxene and amphibole phenocrysts and amphibole megacrysts from unknown Merapi eruptions reveal some similarities. Apparent enrichment to comparable elevated levels of CO2 occurs at a similar H2O content. However, the highest H2O recorded by Nadeau et al. (2013) is only ~2 wt%, even in amphibole megacryst-hosted melt inclusions, which is lower than maximum H2O concentrations recorded by this study.

F, S, Cl

Samples from 2010 show differences in F concentration, depending upon lithology (Fig. 4). Groundmass glass in white pumice samples contains 632–2,199 ppm F, with the peak at between 1,000 and 1,250 ppm, whereas the groundmass glass in the grey scoria encompasses a larger range of F (180–2,637 ppm), with a peak at relatively higher concentrations of 2,000–2,500 ppm (Fig. 4). Fluorine concentrations in 2010 melt inclusions also vary with lithology. Those trapped in clinopyroxene phenocrysts from dense dome clasts and those from grey scoria have a similar range of F, containing up to 1,400 ppm and 1,480 ppm, respectively. White pumice-derived inclusions contain concentrations of F up to 2,390 ppm (Fig. 4). Melt inclusions from 2006 contain up to 2,050 ppm F, with the groundmass glass containing up to 2,349 ppm. Fluorine concentrations in the 2010 and 2006 melt inclusions and groundmass glass are similar, although they extend to both higher and lower concentrations compared to the 1994 Merapi dome-forming eruption (Gertisser 2001). In comparison, plagioclase-hosted inclusions from the 1998 eruption appear to contain less F, up to 700 ppm (Schwarzkopf et al. 2001), although this may be an artefact of the small sample size reported.

Sulphur is present in low concentrations in all groundmass glass, with <100 ppm (detection limit) in 2010 glass and up to 122 ppm in 2006 glass. Melt inclusions are generally more enriched in S than their respective groundmass, ranging up to 535 ppm S in 2010 products and up to 345 ppm in inclusions from the 2006 eruption (Fig. 4). Sulphur concentrations of the 2010 and 2006 melt inclusions and groundmass glass are similar to reported concentrations from the 1994 eruption (Gertisser 2001). A similar range of 200–450 ppm S was also reported for plagioclase-hosted melt inclusions from the 1998 eruption (Schwarzkopf et al. 2001).

Chlorine is more enriched in the melt inclusions than in groundmass glass in both 2010 and 2006 samples (Fig. 4). In melt inclusions, the Cl concentration ranges from 2,060 to 5,130 ppm in 2010 eruptive products, with concentrations most frequently between 2,500 and 3,000 ppm in all sample types. The highest Cl concentrations are found in melt inclusions hosted in clinopyroxene from white pumice samples. Chlorine concentrations in melt inclusions from the 2006 samples show a comparatively narrow range from 2,330 to 3,720 ppm. The groundmass glass concentrations of Cl range from ~900 ppm up to 3,550 ppm in samples from the 2010 eruption and are between ~1,000 and 2,920 ppm in those from 2006. The Cl concentrations in the 2010 and 2006 melt inclusions and groundmass glass are similar to those reported for the 1994 dome-forming eruption (Gertisser 2001), although they extend to both higher and lower values. In comparison, plagioclase-hosted inclusions from recent eruptions contain a similar range of between 3,010 and 3,320 pm Cl (Gertisser 2001), although Schwarzkopf et al. (2001) report high concentrations of up to 7,000 pm Cl in plagioclase-hosted inclusions from the 1998 eruption.

Light lithophile elements (B, Be and Li)

Concentrations of light lithophile elements, especially those of B and Li, indicate differences within the melt inclusion population. Beryllium concentrations are uniform, with all measured melt inclusions containing 1–2 ppm, while Li concentrations vary from 20–68 ppm. When plotted against H2O and Cl (Fig. 5), divergent L-shaped trends show enrichment of Li (>~35 ppm) in melt inclusions from the 2010 dense dome material and the 2006 scoria, which also show low H2O concentrations and ~2,700 ppm Cl. There is no obvious correlation between Li and SiO2 or K2O (Fig. 5). The overall range in B concentration is 35–109 ppm, with enrichment (>~55 ppm) in melt inclusions from white pumice that contain intermediate H2O concentrations (~1–2.5 wt%) and Cl up to ~5,000 ppm (Fig. 5). Boron-enriched inclusions show a positive correlation with SiO2 and K2O, but when plotted against Li, the data show a divergent L-shaped trend (Fig. 5).

Light lithophile element (Li and B) concentrations in melt inclusions, showing that Li is enriched in melt inclusions from the 2010 dense dome clasts and the 2006 scoriaceous dome clasts, and B is enriched in white pumice melt inclusions. a, b Li and B versus P (H2O), c, d Li and B versus H2O, e, f Li and B versus SiO2, g, h Li and B versus Cl, i Li versus B

Clinopyroxene compositions

The major element composition of clinopyroxene host crystals was measured alongside that of other pyroxene phenocrysts within the same eruptive products to establish whether there are systematic compositional variations between different eruptive products and whether host crystals are representative of the clinopyroxene population. Of the 2010 lithologies, clinopyroxene from the dome samples have the widest compositional range (Wo40–50En33–45Fs12–24) with the presence of crystals containing higher proportions of Wo and Fs, and lower En components compared to the grey scoria (Wo42–47En38–44Fs12–15) and the white pumice (Wo41–48En36–45Fs13–16) (Fig. 6). Analysed clinopyroxene phenocrysts from the 2006 dome scoria are similar in composition (Wo41–48En36–45Fs13–17) to those from the 2010 eruption (Table 2). The magnesium number [Mg# = 100 × Mg/(Mg + Fe2+)] of the 2006 pyroxenes (Mg# = 76–83) also overlaps with the range of 2010 phenocrysts (Mg# = 61–86). The 2010 dome samples have the largest range in Mg# (61–86), although most crystals analysed from the dome lie between Mg# 71–84 (Table 2). In comparison, grey scoria and white pumice samples contain clinopyroxene phenocrysts with Mg# = 77–83 and Mg# = 75–84, respectively. Although the majority of clinopyroxene phenocrysts from the 2010 and 2006 samples contain ~1–3 wt% Al2O3, the 2010 dome crystals display the largest variation, with values ranging between 0.4 and 8.9 wt%. Other lithologies from the 2010 eruption also contain relatively high-Al2O3 clinopyroxene, with phenocrysts from the white pumice containing 1.4–7.0 wt% Al2O3 while those from the grey scoria contain 1.4–4.8 wt% Al2O3. These values are similar to previous analyses of 2010 and 2006 Merapi clinopyroxenes, for which concentrations of 2–8 wt% and 1.5–6.5 wt% Al2O3 are reported (Costa et al. 2013). In comparison, the 2006 clinopyroxene samples analysed here generally encompass a more restricted range, with 1.4–3.8 wt% Al2O3, and a single analysis recording an elevated Al2O3 content of 6.7 wt% (Fig. 6). The clinopyroxene phenocrysts hosting the melt inclusions that were used for SIMS analysis sample the compositional range found within the entire 2010 and 2006 clinopyroxene populations, although they do not sample the highest Al2O3 contents, as the analysed host crystals contain a maximum of 5.6 wt% Al2O3 only (see Table 2 and Electronic Supplementary Data).

Clinopyroxene phenocryst compositions. a Al2O3 (wt %) versus Wo (mol%) (wollastonite end-member) of all measured clinopyroxene phenocrysts in 2010 and 2006 products, including the phenocrysts that host melt inclusions used in this paper (white symbols), as well as other phenocrysts from the same eruptive products (black symbols). b Al2O3 (wt %) versus Wo (mol%) in the host phenocrysts, divided into eruptive stages. c Al2O3 (wt %) versus Mg# of all measured clinopyroxene phenocrysts in 2010 and 2006 products, including the host phenocrysts (white symbols) that host melt inclusions used in this paper, as well as other phenocrysts from the same eruptive products (black symbols). d Al2O3 (wt %) versus Mg# in the host phenocrysts, divided into eruptive stages

Discussion

Interpreting SIMS and ATR micro-FTIR H2O and CO2 data

The scatter in melt inclusion H2O and CO2 concentrations in the SIMS data (Fig. 3a), with elevated CO2/H2O compared to equilibrium degassing trends, has frequently been noted in melt inclusions from subduction systems (Atlas et al. 2006; Johnson et al. 2008; Vigouroux et al. 2008; Blundy et al. 2010; Berlo et al. 2012; Nadeau et al. 2013; Reubi et al. 2013). This feature is commonly interpreted as being the result of magma mixing (e.g. Atlas et al. 2006), complex degassing histories, involving CO2 fluxing (Johnson et al. 2008; Vigouroux et al. 2008; Blundy et al. 2010; Nadeau et al. 2013) or non-equilibrium degassing (Gonnermann and Manga 2005), or alternatively, due to post-entrapment diffusive loss of H2O or H+ (Berlo et al. 2012; Reubi et al. 2013). At Merapi, elevated CO2/H2O concentrations in amphibole and pyroxene-hosted melt inclusions have previously been observed and interpreted to reflect CO2 fluxing and the liberation of CO2-rich gas via crustal carbonate assimilation (Nadeau et al. 2013). If a significant amount of CO2 invades the system, the increase in partial pressure of CO2 and corresponding decreasing partial pressure of H2O results in increasing CO2/H2O in the melt, shifting melt inclusion compositions isobarically towards higher CO2 and lower H2O compositions. Crustal assimilation at Merapi has been shown to have played a part in the 2010 and 2006 eruptions of Merapi, evidenced by elevated (compared to mantle values) whole-rock and phenocryst δ18O values (Borisova et al. 2013; Troll et al. 2013). However, the question still remains as to whether CO2 liberation from shallow (<10 km) crustal sediments is likely to be recorded in melt inclusions. At the inferred shallow depth (<10 km) and associated low pressure of crustal CO2 liberation, it is unlikely that the CO2 is redissolved back into the melt. Instead, CO2 is more likely to be lost through fumarolic activity or diffuse degassing (Holloway and Blank 1994; Toutain et al. 2009; Troll et al. 2012). Large increases of CO2/SO2, CO2/HCl and CO2/H2O were detected in fumarolic gases in the months leading up to the 2010 eruption, with a dramatic increase in CO2 abundance from 10 mol% in September 2010 up to 35–63 mol% on 20 October, interpreted to be due to a progressive shift to degassing of a deeper magmatic source (Surono et al. 2012). CO2 fluxing is a process that likely takes place at Merapi and occurred prior to the 2010 and 2006 eruptions, both from depth and from the crust (Surono et al. 2012; Borisova et al. 2013; Troll et al. 2013). However, isobaric dehydration due to CO2 fluxing should result in melt inclusion compositions positioned along isopleth lines on a H2O–CO2 plot and show a relatively continuous range of H2O and CO2 contents (Reubi et al. 2013). The Merapi melt inclusion data (Fig. 3) are inconsistent with this expected trend, and so, although CO2 fluxing may be occurring at Merapi, it is not likely that evidence of this process is preserved in the studied set of melt inclusions.

Diffusive loss of H+ can displace melt inclusion compositions to high CO2 concentrations compared to degassing trends. This process is often accompanied by Fe oxidation and magnetite precipitation (Danyushevsky et al. 2002). Magnetite daughter crystals were noted in some Merapi melt inclusions, but none of these inclusions was chosen for analysis. Significant diffusive loss of molecular H2O is expected to result in crystallisation of daughter crystals and decrepitation of the melt inclusion (Danyushevsky et al. 2002), and has been shown experimentally to cause the formation of shrinkage bubbles (Severs et al. 2007). No decrepitation was observed and although, as noted above, some Merapi melt inclusions contain small daughter crystals, none of these inclusions was chosen for analysis. There is also no correlation between H2O and CO2 content with calculated degree of PEC. Small bubbles were noted occasionally in melt inclusions, indicating that H2O loss may have occurred in a small percentage of inclusions. In the presence of shrinkage bubbles, CO2 values in the melt inclusion would represent minimum values, as CO2 preferentially partitions into the bubble, decreasing the concentration of CO2 in the melt with increasing dehydration (e.g. Bucholz et al. 2013). Sub-micron bubbles, which may not be detected during observation of the melt inclusions, could result in high CO2 values, if sputtered during analysis. However, 12C+ counts were recorded during each cycle of SIMS analysis and counts always remained stable, indicating that CO2 concentrations are homogenous over the spatial extent of each analysis, precluding the possibility that the high CO2 measurements are due to sub-micron bubbles. Diffusive loss of H2O has been shown experimentally to occur on timescales of hours to days in olivine (Portnyagin et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2011; Gaetani et al. 2012). No experimental data for H2O loss from clinopyroxene-hosted melt inclusions are available. However, Reubi et al. (2013) determined that diffusion coefficients for natural pyroxene-hosted melt inclusions are several orders of magnitude smaller than experimentally determined H+ diffusion coefficients (Hercule and Ingrin 1999; Stalder and Skogby 2003), and proved that pyroxene-hosted melt inclusions can preserve H2O values close to entrapment values, even in dome samples formed during low effusions rates (~0.6 m3 s−1). In addition, melt inclusions from slowly cooled samples are more prone to diffusive H2O loss (Hauri et al. 2002; Portnyagin et al. 2008; Lloyd et al. 2013). Therefore, although a small amount of diffusive H2O loss cannot be ruled out, and may possibly account for high CO2/H2O in some melt inclusions from 2006 dome samples, it is unlikely that such a process is the primary cause of the apparently high CO2 values in the white pumice melt inclusions, which are expected to be the fastest erupted and cooled samples in this study.

Comparison of the SIMS data with the ATR micro-FTIR data collected in this study is essential to shed light on the apparently high CO2/H2O melt inclusions in the white pumice. When a subset of the high CO2/H2O inclusions (as measured by SIMS) was subsequently measured by FTIR, no CO2 was detected (detection limit 200 ppm). A possible explanation for the discrepancy could be due to the fact that SIMS measures 12C+ and FTIR measures CO2. Any 12C+ that is present in the melt inclusions as carbonate would not be recorded in the spectrum at 2,350 cm−1, but in the range of 1,400–1,500 cm−1. However, this range was also monitored during FTIR analysis, and no carbonate was detected (detection limit 500 ppm). The discrepancy between the SIMS and ATR micro-FTIR data sets is potentially caused by heterogeneities in the distribution of CO2 in the melt inclusion. The sampling volume of the two techniques is different, with SIMS sampling a smaller region of the inclusion than FTIR. In this respect, FTIR would not detect any heterogeneity, giving only an average CO2 concentration of the inclusion, whereas SIMS analysis will sample a smaller area within each inclusion, possibly enabling the detection of any heterogeneity. The idea of heterogeneous distribution of CO2 in the melt inclusions is supported by the analysis of one melt inclusion that was large enough to be analysed by SIMS in two separate areas, with one measurement of 1,167 ppm CO2 and one of 146 pm CO2. A low CO2 inclusion from the 2006 dome scoria was large enough to analyse twice and both analyses yielded similar results, although other melt inclusions were too small to obtain multiple analyses. Possible causes for the heterogeneous distribution of CO2 in the white pumice melt inclusions may be linked to a post-entrapment process. For example, potential heterogeneity may be linked to the proximity of the SIMS analysis spot with a bubble not in the plane of view. If CO2 diffuses into the bubble, this may possibly result in heterogeneous distribution of CO2 within the inclusion. Although no bubbles were observed in these inclusions, it is possible that they were not in the plane of view or were removed during the polishing process. Another possibility may be that CO2 diffusion, unlike the relatively fast diffusion of H2O (e.g. Zhang et al. 1991), cannot keep up with host crystallisation after entrapment, potentially becoming highly concentrated in some areas and resulting in heterogeneity. This hypothesis may help to explain why apparent CO2 enrichment is only seen in rapidly ejected white pumice samples and not in those from the 2010 dome material, which extruded more slowly, potentially allowing time for re-equilibration of the CO2 in the inclusion. Although beyond the scope of this work, heterogeneous CO2 distribution in natural silicate melt inclusions is an important issue that demands further work to understand fully. If the high CO2/H2O ratios in these inclusions are due to a post-entrapment process, then other melt inclusions showing the same trend need to be interpreted with caution. In the light of this, the apparently elevated CO2 values are reported here but have not been used in the reconstruction of magmatic degassing pathways and equilibration pressures. The remaining CO2 measurements are retained as they reproduce modelled trends for equilibrium degassing, thereby giving additional confidence in results.

Clinopyroxene crystallisation and melt inclusion entrapment

The crystallisation pressures of melt inclusion-hosting clinopyroxene phenocrysts were calculated using three different barometers (Fig. 7). The first is a clinopyroxene-melt model, which is based on the Al partitioning between clinopyroxene and liquid, calibrated for hydrous systems by Putirka (2008, Eq. 32c). The model requires an input of H2O concentration (4 wt% used, as determined by the maximum measured H2O concentration in melt inclusions) and an estimated temperature, calculated using the Putirka et al. (2003) thermometer (range between 1,025 and 1,058 °C). The andesitic to rhyolitic compositions of the melt inclusions and groundmass glass are not in equilibrium with the clinopyroxene host (e.g. the Mg/Fe equilibrium criterion of Putirka (2008) is not met). Therefore, a basaltic andesite bulk rock composition with ~55.5 wt% SiO2 was used, which is representative of the composition of the 2010 and 2006 products and satisfies the equilibrium criteria. The model has a standard error of estimate (SEE) of ± 150 MPa and has recently yielded satisfactory results for similar Indonesian volcanic systems (Dahren et al. 2012; Jeffery et al. 2013). The second barometer is that of Putirka (2008), which is a recalibrated version of Nimis (1995) suitable for hydrous systems and based only upon the clinopyroxene composition. The recalibration aims to remove the systematic error associated with the Nimis (1995) barometer, which can yield low pressure estimates, at the cost of requiring an H2O estimate in addition to the temperature input already needed. The SEE is ± 260 MPa (Putirka 2008). As an additional test, a second clinopyroxene barometer was employed using CpxBar (Nimis 1999), an Excel spreadsheet based upon the pressure-dependent clinopyroxene unit cell arrangement. Calculations for the Merapi clinopyroxenes utilised the mildly alkaline series calibration (standard error: 200 MPa), with a temperature input of 1,050 °C. The range of 2010 clinopyroxene (n = 57) crystallisation pressures obtained by all three models is within error of each other: 80–510 (±150) MPa (Putirka 2008, Eq. 32c), −60 to 430 (±260) MPa (Putirka 2008, Eq. 32b) and 20–540 (±200) MPa (Nimis 1999), equivalent to depths of 2.9–18.6 (±5.5) km, 0–15.7 (±9.5) km and 0.7–19.7 (±7.3) km, respectively (Fig. 7), assuming an average crustal density of 2,800 kg/m3, as also used in depth calculations at Merapi by Costa et al. (2013). Taking into account the pressure range obtained by all three models, crystallisation pressures of the 2006 clinopyroxenes (n = 15) lie within a similar, albeit more restricted range of 120–420 MPa, equivalent to depths of 4.4–15.3 km. One striking feature of the data is that the “deepest” crystals are from the white pumice samples, with 80 % of those crystallised at P > 300 MPa using the Putirka (2008) models (Eq. 32b and 32c), and nearly 80 % of the those crystallised at P > 400 MPa using the Nimis (1999) model, originating from the white pumice (Fig. 7). This is consistent with results from amphibole barometry (Preece 2014), which also suggest that the “deepest” amphibole crystals are from white pumice samples. In comparison, Costa et al. (2013) proposed that the 2010 magma was stored within a multi-depth plumbing system comprising: (1) a deep reservoir at 30 (±3) km or ~800 MPa, as evidenced by some amphiboles and high-Al clinopyroxene, (2) a reservoir at intermediate depths of 13 (±2) km or 300–450 MPa, where other amphiboles, high-Al cpx and high-An plagioclase grew and (3) a shallow reservoir at <10 km (~100 MPa) where extensive crystallisation produced low-Al cpx, orthopyroxene and plagioclase. The clinopyroxenes analysed in this study therefore appear to have crystallised in a depth range consistent with the intermediate and shallow magma storage zones proposed by Costa et al. (2013).

Histograms to show pressure (MPa) of clinopyroxene host crystallisation. a Calculated with CpxBar (Nimis 1999) using the MA (mildly alkaline) calibration at 1,050 °C. b calculated using Equation 32b of Putirka (2008), one value of minus pressure not plotted. c Calculated using Equation 32c of Putirka (2008). d Histogram of last re-equilibration pressures (MPa) of melt inclusions from different 2010 stages and from 2006, calculated using VolatileCalc (Newman and Lowenstern 2002) at 1,050 °C, based on melt inclusion H2O and CO2 concentrations

The wide variation of H2O concentrations in melt inclusions suggests that some inclusions have ruptured on timescales that were long enough to allow the escape of H2O, but not to allow chemical re-equilibration with the groundmass melt (Blundy and Cashman 2005) (Fig. 8). This is consistent with the fact that the melt inclusions with the lowest H2O concentration are from the densest (dome) samples, which have experienced a protracted cooling history at low pressure in the dome. When focussing only on the scoria and pumice samples, the general trend is for lower SiO2 and K2O melt inclusions to have higher H2O concentration than the higher SiO2 and K2O melt inclusions, which is consistent with vapour-saturated crystallisation in response to decompression (Fig. 8). Individual melt inclusion entrapment pressures, or the last pressures of re-equilibration assuming vapour saturation, were calculated using the Papale H2O–CO2 model (Papale et al. 2006), and using VolatileCalc1.1 (Newman and Lowenstern 2002), with both sets of calculations carried out at a temperature of 1,050 °C based upon the clinopyroxene-melt thermometry and previous thermometry of the 2010 products (Costa et al. 2013). Pressure values calculated with each model are similar. Minimum equilibration pressures, assuming volatile saturation, range from <5 to 265 MPa using VolatileCalc. This pressure range is similar to that previously reported for Merapi pyroxene-hosted melt inclusions, which found the majority were trapped below 266 MPa (Nadeau et al. 2013). However, as stated above, the lowest values probably reflect the fact that some melt inclusions have ruptured during ascent. To get a better estimate of the lowest entrapment pressure, the most evolved inclusion that sits on the decompression trend (Fig. 8) can be used, which suggests equilibration at ~16 MPa. Therefore, melt inclusion equilibration depths range between ~0.6 and 9.7 km.

In summary, there is an overlap between clinopyroxene crystallisation and melt inclusion equilibration at the lower end of the pressure range, although clinopyroxene crystallisation continues to greater depths, not reflected in the melt inclusion population. Clinopyroxene phenocrysts crystallised at depths up to ~20 km, with calculated minimum melt inclusion equilibration occurring between 0.6 and 9.7 km. The clinopyroxene barometry results are in agreement with previous clinopyroxene barometry carried on recent eruptive products from Merapi (Gertisser 2001; Chadwick et al. 2013). Clinopyroxene crystallisation depths are also in accord with other geophysical and petrological evidence concerning the magmatic plumbing system of Merapi (e.g. Beauducel and Cornet 1999; Gertisser 2001; Costa et al. 2013). The calculated melt inclusion equilibration pressures complement those previously reported for Merapi (Nadeau et al. 2013). The discrepancy between the higher crystallisation pressure of the host clinopyroxene phenocrysts and the equilibration pressure of the melt inclusions can be explained in several ways. One possible explanation is that the melt was not vapour-saturated at the time of entrapment, therefore recording seemingly lower pressures than those of actual entrapment. This scenario is not considered likely as it is not consistent with the trends of vapour-saturated crystallisation (Fig. 8), nor with the presence of exsolved brine (see below), and is contradictory to previous evidence of volatile-saturated melt inclusions at Merapi (Nadeau et al. 2013). Another interpretation is that the inclusions are not primary but secondary, i.e. not trapped within hosts during initial crystallisation, but instead during subsequent partial dissolution, as previously observed for Merapi melt inclusions in amphibole and pyroxene hosts (Nadeau et al. 2013). However, there is no petrographic evidence for dissolution of the clinopyroxene host crystals that were analysed for this study. Therefore, the most likely explanation for the pressure difference is due to some melt inclusions re-equilibrating with the magma after initial entrapment. This is consistent with the vapour-saturated crystallisation trends, as shown in Fig. 8. The melt inclusions re-equilibrated over a range of pressures <265 MPa (~<10 km), indicating either that there was enough time for re-equilibration during ascent, or, more likely, that magma was stored at this pressure range for a period of time before eruption. The fact that the maximum melt inclusion re-equilibration depth of ~10 km matches that of previous melt inclusion studies (Nadeau et al. 2013), hints at the possibility that the magma has stalled at this depth. This depth is broadly consistent with geophysical (Beauducel and Cornet 1999; Ratdomopurbo and Poupinet 2000) and petrological (Chadwick et al. 2013; Costa et al. 2013) evidence for a magma storage region beneath Merapi. Seismic observations prior to the 2010 eruption detected heightened activity at the beginning of September 2010, with tremors at focal depths of 2.5–5 km depth until 17 October 2010, when activity became shallower and focal depths were <1.5 km (Budi-Santoso et al. 2013; Jousset et al. 2013). This is consistent with ascent of a magma body over 1.5 months prior to eruption (Budi-Santoso et al. 2013) with the depths correlating with those recorded by many of the melt inclusions and shallower crystallised clinopyroxenes.

Degassing history (H2O and CO2)

Using VolatileCalc (at 1,050 °C), trends for open- and closed-system degassing were calculated and compared to the Merapi melt inclusion data. In the open-system model, exsolved volatiles are removed from the system, whereas for closed-system runs, the exsolved vapour remains within the system, acting as a buffer on the remaining melt, including those volatiles that remain in solution in the depressurising magma. Closed-system models fit the data better than open-system ones, with the overall best fit having an initial starting point of 4.0 wt% H2O, 1,000 ppm CO2 and 1 % exsolved vapour (Fig. 3b). This closed-system trend is mainly defined by white pumice inclusions, indicating that closed-system degassing occurred prior to the sub-plinian explosive phase of the 2010 eruption, with the exsolved volatiles staying within the system, thus likely leading to increased overpressure and increased explosive activity. Inclusions from other stages of the eruption have re-equilibrated after the majority of the CO2 was degassed.

Evidence of pre- and syn-eruptive crystallisation and degassing processes from F, S and Cl concentrations

Fluorine generally behaves as an incompatible element, although may be incorporated into certain minerals present in the Merapi mineral assemblage. For example, amphibole from the 2010 eruption has been found to include up to 0.6 wt% F and apatite contains 2.8–5.4 wt% F (Preece 2014). Fluorine concentrations in melt inclusions and groundmass glass (Fig. 4) are similar and within the typical range for subduction related magmas (Aiuppa et al. 2009 and references therein). The results are compatible with the fact that F is highly soluble in silicate melts (e.g. Carroll and Webster 1994), and generally partitions in favour of the melt relative to the vapour phase; therefore, it is often not significantly extracted from the melt by degassing (e.g. Balcone-Boissard et al. 2010).

Melt inclusions from the 2010 eruption contain a range of S from below the detection limit (~100 ppm) up to 535 ppm. Total SO2 emissions for the entire 2010 eruption were calculated at 0.44 Tg, based on satellite observations (Surono et al. 2012). Assuming that the maximum S concentration in the melt inclusions (535 ppm) represents the pre-eruptive volatile content of the melt, and the S concentration in the groundmass glass (<100 ppm) indicates the post-eruptive volatile content, it is possible to calculate the mass and volume of magma needed to produce the 0.44 Tg of SO2 that were emitted during the eruption (Self et al. 2004). The approximate phenocryst content of the 2010 dome samples is ~40 vol%, and taking into account the fraction of felsic to mafic minerals in the rocks, the proportion of phenocrysts is ~45 wt% (i.e. the melt or groundmass occupies 55 wt%). Results indicate that the mass of degassing magma in the 2010 eruption was 9.2 × 1011 kg, and taking into account a melt density of 2,550 kg m−3, calculated from the composition of a typical dome clast using the software Pele (Boudreau 1999), the corresponding melt volume is 0.36 km3. In comparison, it has been estimated that between 0.03 and 0.06 km3 of magma (DRE) was erupted during the 2010 eruption (Surono et al. 2012), an order of magnitude less than the calculated total volume of degassing melt in the system, indicating either that a large proportion of melt did not erupt and remained in the system or that extra sources of volatiles (S) contributed to the volatile budget of the eruption.

The Cl content of the groundmass glass is generally lower than the concentration in the melt inclusion population, indicating Cl exsolution at low pressures during syn-eruptive degassing (Fig. 9). The Cl concentrations in the melt inclusions are similar to other arc magmas (Aiuppa et al. 2009 and references therein). Melt inclusion Cl concentrations range between 2,060 and 5,130 ppm, although nearly 90 % of the data in this study range between 2,400 and 3,400 ppm (Fig. 9), with the higher concentrations only observed in white pumice melt inclusions. The simplest explanation for a relatively limited range of Cl in the melt inclusions, regardless of variations in H2O, could be that the magma underwent decompression degassing with preferential loss of H2O and no apparent loss of Cl (Webster et al. 2010; Mann et al. 2013). However, an alternative explanation is that the silicate melt was in equilibrium with a magmatic hydrosaline chloride liquid ± vapour (e.g. Lowenstern 1994; Shinohara 1994; Webster 1997, 2004). Chlorine concentrations in the silicate melt are “buffered” and so remain constant as Cl reaches its solubility limit in equilibrium with the liquid phase(s). Similar indirect geochemical evidence for the presence of a hydrosaline chloride liquid from melt inclusion data has been reported at Mount Hood (Koleszar et al. 2012), the Bandelier Tuff, Valles Caldera (Stix and Layne 1996) and Vesuvius (Signorelli et al. 1999; Fulignati and Marianelli 2007). The Cl concentrations in the Merapi melt inclusions are similar to saturation values for felsic melts determined experimentally (e.g. Métrich and Rutherford 1992; Webster 1997) as well as the values recorded in natural felsic melt inclusions interpreted to have been in equilibrium with a Cl-rich liquid (Stix and Layne 1996; Koleszar et al. 2012). This evidence for the presence of a saline liquid or “brine” phase is corroborated by the Li and B data (see section below).

Concentration of Cl versus H2O in melt inclusions. Melt inclusions from the 2010 samples as well as from the 2006 scoriaceous dome show constant Cl concentrations with variable H2O contents, providing evidence that the Cl concentration in the melt was “buffered” by a hydrochloride phase. The only inclusions that deviate to higher Cl concentrations are several from the white pumice

Li and B enrichment

Lithium is enriched in melt inclusions from the 2010 dense dome material and the 2006 scoria, which contain relatively low concentrations of H2O. It displays an L-shaped, divergent trend when plotted against H2O and Cl and displays no correlation with SiO2 or K2O (Fig. 5). Enrichment of B occurs in melt inclusions from white pumice samples, which have mid-range H2O content, with variable Cl, including elevated contents. These contrasting features indicate that Li and B enrichment are produced by different processes, corroborated by the decoupled relationship of Li versus B (Fig. 5) as well as the fact that enrichment occurs in distinct and separate lithological types.

Lithium-enriched inclusions, only detected in 2010 dense dome samples and 2006 scoriaceous dome samples, have last equilibrated at near-surface depths, with the maximum Li enrichment in 2010 inclusions at \( {\text{P}}_{{{\text{H}}_{ 2} {\text{O}}}} \) = 14.5 MPa (0.5 km depth) and \( {\text{P}}_{{{\text{H}}_{ 2} {\text{O}}}} \) = 36.5 MPa (1.3 km depth) for maximum Li in 2006. This implies that Li enrichment is a pressure-mediated process. Lithium enrichment in early erupted dome samples, detected in melt inclusions equilibrated at specific H2O concentrations, has also been noted at Mount St. Helens (Berlo et al. 2004; Blundy et al. 2008) and at Shiveluch (Humphreys et al. 2008). This has been attributed to pre-eruptive, vapour-mediated transfer of Li, derived from deeper within the magma transport system. Alternatively, Li-rich inclusions may be produced via re-equilibration with a Li-rich brine phase (Kent et al. 2007). An alkali-rich aqueous vapour can be produced via the degassing of an H2O-saturated magma body. Buoyant upward migration of this vapour results in its exsolution to produce two phases: a dense alkali-rich brine and a lower density H2O-rich vapour (Kent et al. 2007). The lower density H2O-rich vapour is subsequently lost via degassing and the alkali-rich brine re-equilibrates with the melt, resulting in Li-enriched melt inclusions. Gas measurements and mass balance models (Nadeau et al. 2013) also predict the presence of a brine phase below Merapi and suggests that the volatile phase is exsolved as a single supercritical fluid below at least 5 km depth and exsolves directly as vapour + brine phases above this critical depth. In the Merapi melt inclusions, the Li-enriched inclusions all contain similar Cl concentrations (Fig. 5), further indicating that Li-enrichment occurred during “buffering” of the melt Cl concentrations, related to equilibration of the melt with the brine phase. The inflexed trend in SiO2 versus Na2O, with decreasing Na2O in the groundmass glass (Fig. 2), may also be attributed to Na partitioning into the exsolving fluid phase during volatile-saturated crystallisation (Blundy et al. 2008).

The behaviour of B in magmatic and hydrothermal systems is complex and previous studies have reached differing conclusions as to whether B partitions preferentially into the melt or into the aqueous phase(s) (e.g. Pichavant 1981; Webster et al. 1989; Heinrich et al. 1999; Hervig et al. 2002; Schatz et al. 2004). Recent studies of natural samples have shown that transient B depletion and enrichment may be related to changing degassing regimes (Menard et al. 2013; Vlastélic et al. 2013) or alternatively enrichment may occur due to crystallisation and magmatic fractionation (Wright et al. 2012). In the Merapi melt inclusions, the correlation of B with SiO2 indicates that B behaves as an incompatible element. The enrichment of B with crystallisation shows that B remained in the melt, suggesting a low vapour-melt partition coefficient, as also observed, for example, in melt inclusions from Crater Lake (Wright et al. 2012). One possible control on the partitioning behaviour of B is the NaCl content of the brine and vapour, as higher B solubility is expected in melts which are in equilibrium with saline brines (Schatz et al. 2004). Therefore, the enrichment of B in the Merapi melt may be due to the presence of the brine which acted to increase B solubility in the melt, allowing the incompatible B to become enriched in the melt during crystallisation.

Driving forces behind the 2010 eruption and comparison with the 2006 eruption

In many respects, the contrasting behaviour of the 2010 and 2006 eruptions is not reflected in the investigated eruptive products. Whole rock, melt inclusion and groundmass compositions are all similar in terms of major elements and volatile (H2O, CO2, F, Cl and S) concentrations are predominantly similar also. Whole-rock compositions are similar for the 2010 and 2006 erupted lavas and remained nearly constant throughout the duration of each eruption. This indicates that bulk magmatic composition cannot be a major factor in the change in behaviour between the two basaltic andesite eruptions. However, there are some differences between the products, particularly in melt inclusions originating from the white pumice, which is unique to the 2010 eruption. The white pumice clasts show numerous distinctive features when compared to other 2010 samples and reveal evidence of an increase in deep magma supply, highlighted by an abundance of clinopyroxene phenocrysts that crystallised at >11–15 km depth (>300–400 MPa) (Fig. 10). This is in agreement with other petrological and monitoring data (Surono et al. 2012; Costa et al. 2013; Jousset et al. 2013). Increasing fumarole gas temperatures and ratios of CO2/SO2, CO2/HCl and CO2/H2O in months prior to the 2010 eruption, were interpreted to be due to the degassing of a deep magmatic source (Surono et al. 2012). Costa et al. (2013) proposed that the 2010 eruption was preceded by an influx of deeper, hotter, more volatile-rich magma that was up to 10 times more voluminous than that in 2006. Melt inclusions from grey scoria and white pumice clasts also preserve evidence of closed-system conditions during ascent, with higher H2O concentrations compared to the dome melt inclusions. Volatile concentrations in melt inclusions from white pumice clasts fit with modelled concentrations predicted for a closed-system in equilibrium with 1 % exsolved volatiles. A deep influx of magma would have caused increased overpressure and faster magma ascent. Closed-system degassing and fast magma ascent rates, as a result of the deep influx of magma, were key driving forces behind the explosive nature of the 2010 eruption. Closed-system degassing likely sustained explosive behaviour, generating a sub-plinian convective column, which collapsed to produce the scoria- and pumice-rich PDCs during Stage 6 of the 2010 eruption. The continuous range of melt inclusion re-equilibration at depths between 9.7 and 0.6 km suggests that the melt region, at these depths at least, is interconnected and not formed by isolated chambers (Fig. 10).

Silicate melt from early-erupted products (i.e. dome clasts) of both 2010 and 2006 was saturated in Cl, preserving evidence of the presence of a hydrosaline fluid or “brine” phase within the magmatic system prior to each eruption. Further evidence for this comes from the fact that these same melt inclusions are enriched in Li, indicating similar shallow-level processes operating prior to the dome-building stage of each eruption, in agreement with Nadeau et al. (2013). White pumice melt inclusions are enriched in B, which was stabilised in the melt rather than degassing, due to the presence of the brine phase. It acted as an incompatible element, thereby becoming enriched in the melt during fractional crystallisation.

Although the melt inclusions and their clinopyroxene hosts in this study have shed light on the magmatic system and magmatic contributions to the eruptive behaviour of Merapi during 2010 and 2006, other factors are likely to have contributed to the eruptive dynamics. Shallow-level degassing and crystallisation of microlites, likely not reflected in melt inclusion data, have been associated with increasing overpressure, changing degassing regimes and increasing explosivity in 2010 (Preece 2014). Previous workers (e.g. Chadwick et al. 2007; Deegan et al. 2010; Troll et al. 2012, 2013; Borisova et al. 2013) have proposed that CO2 liberation via crustal carbonate assimilation has the potential to sustain and intensify eruptions at Merapi. Monitoring data of the 2010 eruption indicate large CO2 emissions prior to the 2010 eruption (Surono et al. 2012), and previous melt inclusions have been interpreted to reflect CO2 fluxing at Merapi (Nadeau et al. 2013). However, in contrast to previous studies (Nadeau et al. 2013), the CO2 data and trends collected during this study cannot be reliably attributed to CO2 fluxing due to the apparent heterogeneous distribution of CO2 in some of the melt inclusions. The peak of the 2010 eruption was preceded by a regional tectonic earthquake. On 4 November 2010, a M4.2 earthquake occurred ~200 km south of Merapi, at 23:56 local time, just prior to the climactic phase of 5 November. Several authors have suggested a probable connection between regional seismic activity and the intensification of eruptive activity at Merapi (e.g. Walter et al. 2007; Surono et al. 2012; Troll et al. 2012; Jousset et al. 2013). Although Jousset et al. (2013) stress that the main factor causing over-pressurisation at Merapi in 2010 was related to magmatic influx and ascent, it is possible that with the magmatic system already at a critical pressurised stage, a small external force can affect the gas phase, promoting rapid degassing, fragmentation and eruption of an already unstable system (e.g. Brodsky et al. 1998; Davis et al. 2007; Walter et al., 2007).

The melt inclusions and clinopyroxene hosts shed light on the magmatic plumbing system prior to the two most recent eruptions of Merapi and reveal an influx of deeper magma during the 2010 eruption, which was a key factor in determining the eruptive dynamics of the cataclysmic 2010 eruption. However, in addition to this, the influence of factors such as shallow-level degassing and crystallisation feedback mechanisms, carbonate assimilation and regional earthquakes should not be ignored.

Conclusion

Using melt inclusions and their clinopyroxene hosts, this study has revealed information about the pre-2010 and pre-2006 Merapi magma system, and key factors that contributed to the cataclysmic events of 2010. Despite the contrasting eruptive behaviour, the 2010 and 2006 eruptive products are remarkably similar in terms of bulk rock and melt inclusion major element concentrations. In addition, volatile contents of both melt inclusions and groundmass glass are also similar. The continuous range of melt inclusion re-equilibration at depths <10 km suggests that the melt region, at these depths at least, is interconnected and not formed by isolated chambers. Dome fragments from both eruptions reveal evidence of an exsolved brine phase prior to eruption, with melt inclusions from these clasts enriched in Li and with “buffered” Cl concentrations. In addition, melt inclusions from the 2010 white pumice formed during explosive activity and which equilibrated during closed-system degassing, are enriched in B, which was stabilised in the melt due to the presence of the brine phase. Clinopyroxene host phenocrysts from the white pumice crystallised at greater depths (up to 20 km) compared to those erupted during other stages of the 2010 eruption or those from 2006. The transition from effusive dome-forming to explosive (sub-plinian) behaviour during the 2010 eruption was triggered by an influx of magma from depth which increased the overpressure and “overwhelmed” the system. This was further increased by a closed-system degassing regime, with exsolved volatiles staying in the system. Careful melt inclusion analysis, utilising various complementary techniques including SIMS and ATR micro-FTIR revealed heterogeneous CO2 distribution in some melt inclusions, thought to have formed during post-entrapment modifications, and highlights the need for caution in melt inclusion studies. This work emphasizes the influence of magmatic flux, and magmatic degassing in controlling the eruptive style at Merapi volcano. Variations in these factors will serve to modulate future activity, controlling whether eruptions will be effusive and dome-forming or more explosive.

References

Aiuppa A, Baker DR, Webster JD (2009) Halogens in volcanic systems. Chem Geol 263:1–18

Allard P, Métrich N, Sabroux J-C (2011) Volatile and magma supply to standard eruptive activity at Merapi volcano, Indonesia. Geophys Res Abstr 13:EGU2011-13522

Andreastuti SD, Alloway BV, Smith IEM (2000) A detailed tephrostratigraphic framework at Merapi volcano, Central Java, Indonesia: implications for eruption predictions and hazards assessment. J Volcanol Geoth Res 100:51–67

Atlas ZD, Dixon JE, Sen G, Finny M, Lillian A, Pozzo MD (2006) Melt inclusions from Volcán Popocatépetl and Volcán de Colima, Mexico: melt evolution due to vapor-saturated crystallization during ascent. J Volcanol Geoth Res 153:221–240

Baker DR (2008) The fidelity of melt inclusions as a record of melt composition. Contrib Miner Petrol 156:377–395

Balcone-Boissard H, Villemant B, Boudon G (2010) Behaviour of halogens during the degassing of felsic magmas. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 11:Q09005

Beauducel F, Cornet FH (1999) Collection and three- dimensional modeling of GPS and tilt data at Merapi volcano, Java. J Geophys Res 104:725–736

Berlo K, Blundy J, Turner S, Cashman K, Hawkesworth C, Black S (2004) Geochemical precursors to volcanic activity at Mount St. Helens, USA. Science 306:1167–1169

Berlo K, Stix J, Roggensack K, Ghaleb B (2012) A tale of two magmas, Fuego, Guatemala. Bull Volc 74:377–390

Blundy J, Cashman K (2005) Rapid decompression-driven crystallisation recorded by melt inclusions from Mount St. Helens volcano. Geology 33:793–796

Blundy J, Cashman K (2008) Petrologic reconstruction of magmatic system variables and processes. Rev Mineral Petrol 69:179–239

Blundy J, Cashman KV, Berlo K (2008) Evolving magma storage conditions beneath Mount St. Helens inferred from chemical variations in melt inclusions from the 1980–1986 and current (2004–2006) eruptions. In: Sherrod DR, Scott WE, Stauffer PH (Eds) A volcano rekindled: the renewed eruption of Mount St. Helens, 2004–2006. US Geol Surv Prof Pap 1750, pp. 755–790

Blundy J, Cashman KV, Rust A, Witham F (2010) A case for CO2-rich arc magmas. Earth Planet Sci Lett 290:289–301

Borisova AY, Martel C, Gouy S, Pratomo I, Sumarti S, Toutain J-P, Bindeman IN, de Parseval P, Metaxian J-P, Surono (2013) Highly explosive 2010 Merapi eruption: evidence for shallow-level crustal assimilation and hybrid fluid. J Volcanol Geoth Res 261:193–208

Boudreau AE (1999) PELE-a version of the MELTS software program for the PC platform. Comput Geosci 25:201–203

Brodsky EE, Sturtevant B, Kanamori H (1998) Earthquakes, volcanoes, and rectified diffusion. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 103:23827–23838

Bucholz CE, Gaetani GA, Behn MD, Shimizu N (2013) Post-entrapment modification of volatiles and oxygen fugacity in olivine-hosted melt inclusions. Earth Planet Sci Lett 374:145–155

Budi-Santoso A, Lesage P, Dwiyono S, Sumarti S, Surono, Subandriyo, Jousset P, Metaxian J-P (2013) Analysis of the seismic activity associated with the 2010 eruption of Merapi Volcano, Java. J Volcanol Geoth Res 261:153–170

Camus G, Gourgoud A, Mossand-Berthommier P-C, Vincent P-M (2000) Merapi (Central Java, Indonesia): an outline of the structural and magmatological evolution, with special emphasis to the major pyroclastic events. J Volcanol Geoth Res 100:139–163

Carroll MR, Webster JD (1994) Solubilities of sulfur, noble gases, nitrogen, chlorine and fluorine in magmas. In: Carroll MR, Holloway JR (eds) Volatiles in magmas. Rev Mineral Geochem 30:231–279

Chadwick JP, Troll VR, Ginibre C, Morgan D, Gertisser R, Waight TE, Davidson JP (2007) Carbonate assimilation at Merapi Volcano, Java, Indonesia: insights from crystal isotope stratigraphy. J Petrol 48:1793–1812