Abstract

The rigidity of the real semisimple Lie algebra \({\mathfrak {so}}(4,1)\) was first proved in a brief paper published by Fantappiè in 1954 (Rend. Accad. Lincei Ser. VIII 17:158–165, 1954). The purpose of this note is to provide some historical context for this work and discuss why no further developments of this result were pursued by Italian mathematicians at the time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Zornoff Táboas (2008) for a detailed description of Fantappiè’s influences on Brazilian mathematics.

An effective construction of relativistically invariant functional products; MR 0044942.

Strumenti matematici della fisica moderna e Teoria Unitaria dell’Universo.

Gruppi topologici e loro applicazioni fisiche.

Il lavoro di U. Amaldi [\(\ldots \)] passò praticamente inosservato. La cosa non deve stupire se si considera che anche gli importantissimi lavori di Cartan sui gruppi continui finiti non furono praticamente letti fino agli anni ’60.

“Da quanto precede, infine, segue allora che, come già per la classificazione delle geometrie data da Klein nel suo programma di Erlangen, anche per le “fisiche” possibili, o meglio per gli “universi fisici” possibili, sopra specificati, la classificazione piú naturale che si può fare è proprio quella che si ottiene in base al gruppo fondamentale, che serve a definire l’uguaglianza.”

Also referred to as the group of inhomogeneous Lorentz transformations.

“Può accadere che il gruppo di Lorentz, che indicheremo con \({\mathrm {Lz}}_{3+1}^{10}\) (a 10 parametri) nella progressiva evoluzione delle nostre conoscenze scientifiche, finisca col subire una sorte analoga a quella del gruppo di Galileo \({\mathrm {Gl}}_{3+1}^{10}\) (pure a 10 parametri) della fisica classica, e cioè finisca con l’essere sostituito da un altro gruppo più generale, per esempio dal gruppo \({\mathrm {Ds}}_{3+1}^{10}\) dei movimenti in sè del cronotopo di De Sitter, che da proprio il gruppo di Lorentz come caso limite, quando il raggio di curvatura del cronotopo tende all’\(\infty \), così come il gruppo di Lorentz da come caso limite il gruppo di Galileo, quando la velocità della luce si fa tendere all’\(\infty \).”

\(E\) in questa Nota mostreremo, per l’appunto, che il gruppo di Lorentz è proprio il caso limite di un “altro” gruppo, dipendente con continuità da un parametro \(R\), per \(R=\infty \), e poiché dimostreremo che questo nuovo gruppo non può più essere limite di un altro gruppo diverso, chiameremo questo nuovo gruppo il gruppo finale, e lo indicheremo con \({\mathrm {Fn}}^{10}_{3+1}\).

Ora, le informazioni più sicure, che si possono avere nel caso più generale, sono evidentemente quelle che, riferendosi a caratteristiche espresse da numeri interi (le quali non possono variare con continuità) debbono coincidere con quelle note, del caso limite.

It is maybe worthwile to recall here that, as mentioned, Bianchi was Fantappiè’s thesis advisor and most probably his main source of informations for anything concerning differential geometry.

The choice of giving a special notation like \({\mathrm {Fn}}_{3+1}^{10}\) for what is nothing but a pseudo-orthogonal group is not completely clear. On one hand, it is obvious that \({\mathrm {Fn}}\) stands for final. On the other hand since \({\mathrm {Lz}}\) stands for Lorentz and \({\mathrm {Ga}}\) for Galilei, it is difficult not to guess that \({\mathrm {Fn}}\) could stand also for Fantappiè and to ask oneself whether such ambiguity is intended.

An invariant subgroup \(H\) in \(G\) identifies, via integration, a Lie ideal \({\mathfrak {h}}\subseteq {\mathfrak {g}}\). By choosing a suitable basis of \({\mathfrak {g}}\), one can indeed transform the ideal condition \([x,h]\in {\mathfrak {h}}, \forall h\in {\mathfrak {h}}, \forall x\in {\mathfrak {g}}\) into vanishing of a subset of structural constants with respect to this basis.

Si può osservare infatti che la presenza di un sottogruppo invariante si traduce nell’annullarsi di varie costanti di struttura e quindi la semplicità del gruppo si traduce nel fatto che almeno alcune di queste costanti debbono essere diverse da zero. Se quindi un gruppo semplice è limite di un altro gruppo, con lo stesso numero di parametri, si ottiene cioé da un altro, dipendente con continuità da una variabile \(\alpha \) per \(\alpha \rightarrow \alpha _0\), anche le costanti di struttura di questo dipenderanno con continuitá da \(\alpha \), e quindi tutte quelle che sono diverse da \(0\) per \(\alpha =\alpha _0\), resteranno pure \(\ne 0\) per \(\alpha \) abbastanza prossimo ad \(\alpha _0\). In particolare, dunque, se il gruppo limite è semplice, anche il gruppo variabile deve essere semplice per \(\alpha \) vicino ad \(\alpha _0\), cioé un gruppo semplice non può essere limite che di un gruppo pure semplice.

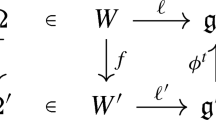

\(\mu _0\) Is the semisimple Lie algebra structure whose rigidity we would like to show.

It is no surprise the theory of smooth vectors in unitary irreps will be definitely set up by Eward Nelson, one of the first Ph.D.’s students of Segal.

The plural here refers to the fact that from a purely Lie theory point of view the Poincaré group may be reached as a contraction both of \(\text {SO}(4,1)\) and \(\text {SO}(3,2)\). A possibility that in Fantappiè (1952) is excluded by requirements on the signature of the space-time manifold.

The inhomogeneous Lorentz group.

“The above considerations show a certain similarity with those of I.E. Segal. However, Segal’s considerations are more general than ours as he considers a sequence of Lie groups the structure constants of which converge towards the structure constants of a non isomorphic group. In the above, we have considered only one Lie group but have introduced a sequence of coordinate systems therein and investigated the limiting case of these coordinate systems becoming singular. As a result of our problem being more restricted we could arrive at more specific results.” (Inönü and Wigner 1952, p. 514).

This historical note was presented for publication in the proceedings of the mentioned Workshop. However, such proceedings were never published. It is possible to find it on the internet at http://ysfine.com/wigner/inonu.

References

AA.VV. 1972. Luigi Fantappiè: scienziato e matematico, R. Scipio ed., Viterbo: Agnesotti

Arcidiacono, G. 1988. L’universo di De Sitter, il gruppo di Fantappiè e la cosmologia del Big Bang. Collect. Math. 39: 55–65.

Baez, J.C., et al. 1999. Irving Ezra Segal 1918–1998. Notices of the American Mathematical Society 6: 659–668.

Bergia, S. 2005. Il contributo italiano alla relatività. Boll. U.M.I. Serie VIII 8: 261–287.

Bianchi, L. 1918. Lezioni sulla teoria dei gruppi continui finiti di trasformazioni. Pisa: Spoerri.

Brigaglia, A., and Scimone, A. 1998. Algebra e teoria dei numeri, in La Matematica italiana dopo l’unità. Milano: Marcos y Marcos.

Cartan, E. 1914. Les groupes réels simples finis et continus. Annales Scientifiques École Normale Sup. Paris 31: 263–355.

Cartan, E. 1929. Groupes simples clos et ouverts et géométrie riemannienne. Journ. Math. Pures et Appl. 8: 1–34.

Cogliati, A. 2014. Early history of infinite continuous groups, 1883–1898. Hist. Math. 41: 291–332.

Dyson, F.J. 1972. Missed opportunities. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 78: 635–652.

Evola, J. 1940. Gli ebrei e la matematica. Difesa della razza 3: 24–28.

Fantappiè, L. 1973. Opere Complete, vol. 2. Rome: Unione Matematica Italiana.

Fantappiè, L. 1949. Fantappiè, Costruzione effettiva dei prodotti funzionali relativisticamente invarianti. Ann. Di Mat. s. 4 XXIX: 43–69.

Fantappiè, L. 1952. Caratterizzazione analitica delle grandezze della meccanica quantica. Rend. Accad. Lincei Ser. VIII 12: 285–290.

Fantappiè, L. 1954. Su una nuova teoria di relatività finale. Rend. Accad. Lincei Ser. VIII 17: 158–165.

Fantappiè, L. 1955. Deduzione autonoma dell’equazione generalizzata di Schrödinger, nella teoria di relatività finale. Rend. Accad. Lincei Ser. VIII 19: 367–373.

Fantappiè, L. 1959. Sui fondamenti gruppali della fisica. Collect. Math. 9: 77–136.

Fantappiè, L. 1961. I gruppi topologici. Ed. F. Succi. Indam Lectures, Roma: Docet.

Fantappiè, L. 1993. Conferenze Scelte, Roma: Di Renzo.

Fichera, G. 1957. La vita matematica di L. Fantappiè. Rend. Mat. XVI: 143–160.

Gambini, G., and L. Pepe. La raccolta di Fantappiè di opuscoli nella biblioteca dell’Istituto Matematico della Università di Ferrara, preprint, Università di Ferrara.

Gerstenhaber, M. 1964. On the deformations of rings and algebras. Annals of Mathematics 79: 59–103.

Goodstein, J., and D. Babbit. 2012. A fresh look at Francesco Severi. Notices of the American Mathematical Society 9: 1064–1075.

Goze, M., and Lutz. 1981. Nonstandard Analysis: A practical guide with applications, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol. 881. Berlin: Springer.

Guerraggio, A., and P. Nastasi. 2005. Matematica in camicia nera - il regime e gli scienziati. Milano: B. Mondadori.

Hawkins, T. 2000. Emergence of the theory of Lie groups, An Essay in the History of Mathematics 1869–1926, Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. New York: Springer.

Inönü, E. 1997. A historical note on group contractions. In Workshop on Quantum Groups, Deformations and Contractions. http://ysfine.com/wigner/inonu.pdf.

Inönü, E., and E. Wigner. 1952. Representations of the Galilei group. Nuovo Cimento 9: 705–718.

Inönü, E., and E. Wigner. 1953. On the contraction of groups and their representations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 39: 510–524.

Lévy-Nahas, M. 1967. Deformation and contraction of Lie algebras. Journal of Mathematical Physics 8: 1211–1223.

Lützen, J. 1982. The prehistory of the theory the distributions, Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences, vol. 7. New York: Springer.

Minkowski, H. 1909. Raum und Zeit. Physics Zeitschrift 10: 104–111.

Nijenhuis, A., and R.W. Richardson Jr. 1964. Cohomology and deformations of algebraic structures. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 70: 406–411.

Pastrone, F. 1998. Fisica Matematica e Meccanica Razionale, in La Matematica italiana dopo l’unità. Milano: Marcos y Marcos.

Roghi, G. 2005. Materiale per una Storia dell’Istituto Nazionale di Alta Matematica dal 1939 al 2003, 3–290. VIII-A: Boll. U.M.I. La Matematica nella Società e nella Cultura Ser. VIII.

Rogora, E. 2008. In L’opera di Ugo Amaldi nel contesto della diffusione delle idee di Sophus Lie in Italia, Conferenze, E. Rogora ed., Roma: Nuova Cultura.

Segal, I.E. 1951. A class of operator algebras which are determined by groups. Duke Mathematical Journal 18: 221–265.

Struppa, D.C. 1987. Luigi Fantappiè and the theory of analytic functionals, in Italian Mathematics between the two World Wars (Milan/Gargnano 1986), 393–429. Bologna: Pitagora.

Thomas, L.H. 1941. On unitary representations of the group of De Sitter space. Annals of Mathematics 42: 113–126.

Weil, A. 1992. The apprenticeship of a mathematician. Boston: Birkhäuser. (Original edition: Souvenirs d’Apprentissage, Birhäuser (1991).

Zornoff Tàboas, P. 2008. Très momentos no desenvolvimento da Teoria dos Funcionais Analíticos segundo Luigi Fantappiè. Revista Brasileira de História da Matemática 8: 1–12.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Prof. M. C. Nucci for encouraging me to write these notes and Prof. D. Struppa and Prof. Michael McNeil for generously devoting their time to improve an earlier version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by: Umberto Bottazzini.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ciccoli, N. Fantappiè’s “final relativity” and deformations of Lie algebras. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 69, 311–326 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-015-0151-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-015-0151-2