Abstract

Background

Depression and anxiety are common mental disorders in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC); however, it remains unclear whether they are related to cancer mortality.

Method

Based on a systematic literature search, 12 eligible studies involving 26,907 patients with CRC were included in this study.

Results

Univariate analysis revealed that anxiety was associated with an all-cause mortality rate of 1.42 (1.02, 1.96), whereas multivariate analysis revealed that anxiety was not associated with an all-cause mortality rate of 0.73 (0.39, 1.36). In univariate and multivariate analyses, depression was associated with all-cause mortality rates of 1.89 (1.68, 2.13) and 1.62 (1.27, 2.06), respectively, but not with the cancer-associated mortality rate of 1.16 (0.91, 1.48) in multivariate analyses. Multivariate subgroup analysis of depression and all-cause mortality showed that younger age (≤65 years), being diagnosed with depression/anxiety after a confirmed cancer diagnosis, and shorter follow-up time (<5 years) were associated with poor prognosis.

Conclusions

Our study emphasizes the key roles of depression and anxiety as independent factors for predicting the survival of patients with CRC. However, owing to the significant heterogeneity among the included studies, the results should be interpreted with caution. Early detection and effective treatment of depression and anxiety in patients with CRC have public health and clinical significance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer death [1]. Although the number of long-term survivors of CRC has increased due to advances in testing and treatment, approximately 50% of the population has reported high mortality rates within 10 years of diagnosis [2]. Multiple factors are known to affect the survival rate of patients with CRC. Certain immutable factors are associated with reduced survival rate, such as cancer characteristics, including advanced and proximal tumors [3]. However, > 50% of cases and deaths can be attributed to modifiable risk factors, such as smoking, unhealthy diet, excessive alcohol consumption, lack of exercise, and being overweight, making prevention possible [4]. Thus, it is crucial to identify the modifiable factors that affect CRC-related mortality to improve prognosis and overall survival in patients.

Mental disorders are one of the main causes of disability and premature death worldwide [5]. Depression and anxiety are the most common mental disorders, with prevalence rates of 5% and 7% in the general population over the past year [6]. Importantly, depression and anxiety are more common among patients with cancer, affecting 20% and 10% of them, respectively [7]. The impact of CRC on the body and its functions may have further adverse psychological effects on the overall health and quality of life of patients. Therefore, patients with CRC suffer from negative emotions under chronic psychological pressure. In 2019, Peng et al. [8] published a literature review of 15 studies and reported that the prevalence rates of anxiety and depression in patients diagnosed with CRC were 1.0–47.2% and 1.6–57%, respectively. Studies have also shown that patients with CRC have a 51% increased risk of depression after diagnosis (pooled hazard ratio (HR), 1.51; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.10–2.09) but have no association with anxiety (pooled HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 0.79–2.57) [9]. In addition, in 2021, a cohort study in Denmark reported that patients with CRC had a significantly higher risk of depression than cancer-free individuals, even after participating in the study for 5 years (HR, 2.65; 95% CI, 1.61–4.36) [10]. Although psychological factors are widely known to predict colorectal cancer-associated mortality, studies have reported inconsistent results; some studies have revealed that depression is associated with an increase in all-cause mortality [2, 11, 12], whereas others have indicated that it is not associated with mortality [13]. Similarly, studies have shown inconsistent relationships between anxiety and all-cause mortality in patients with CRC, with some studies suggesting a correlation [14, 15], whereas another study showing no correlation [16]. Moreover, conflicting conclusions have been drawn regarding the specific mortality rate of patients with CRC [13, 17]. Thus, there is a need for comprehensive and rigorous research to determine the relationship of depression and anxiety with the survival and progression of patients with CRC.

Therefore, we conducted a comprehensive and rigorous meta-analysis to understand the relationship of depression and anxiety with CRC.

Methods

Protocol and guidance

This study was conducted based on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [18] and AMSTAR (Assessing the methodological quality of systematic reviews) [19] guidelines. The protocol for this review has been registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023414631). The need for ethical approval or informed consent in this study was waived.

Search strategy

Based on the recommendations of the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology group [20], we searched the following electronic databases for articles written in English published from inception until March 26, 2023: PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library. The following search terms were used: (“colon cancer” or “colon tumor” or “colorectal cancer” or “colorectal cancer”) and (“depression” or “anxiety”) and (“survival” or “mortality” or “metastasis” or “recurrence”). The search strategy was implemented using a combination of index words and free text keywords. In addition, the reference lists in these articles were evaluated to include more comprehensive studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The criteria for the inclusion of studies were as follows: (1) cohort study, (2) survey of patients with CRC, (3) assessment of depression or anxiety according to standard diagnostic criteria or self-reported scale, and (4) provision of HRs or risk ratios and 95% CIs for all-cause or cancer-specific mortality. Further, the exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies involving participants with malignant tumors other than CRC, (2) studies involving patients with cancer but without depression or anxiety, and (3) studies with insufficient data.

The data were independently extracted by two authors (SJX and LJM). In the event of disputes and disagreements, a third author (LCY) was consulted to reach a consensus. This review collected the following details: name of the lead author, year of publication, country, number of participants, age, time of depression assessment, depression/anxiety measurement method, and follow-up time.

All selected articles were examined using the quality assessment scale of the Newcastle Ottawa cohort study. This semiquantitative scale uses a star rating system to evaluate the quality of eight projects in three areas: selection (four projects, one star per project), comparability (one project, up to two stars), and exposure (three projects, one star per project). In this meta-analysis, we classified the quality as good (≥ 7 stars), average (4–6 stars), or poor (< 4 stars).

The outcomes were all-cause (death from any cause) and CRC-specific (death due to CRC as well as depression and anxiety) mortality rates of patients with CRC. This assessment is based on the HRs and 95% CIs obtained from each study. Most HRs are adjusted for different variables, such as age or tumor staging. Unadjusted HR for univariate analysis; conduct a multivariate analysis on the adjusted HR. Subgroup analysis was conducted based on age (mean age, ≤ 65 vs. > 65 years), follow-up time (< 5 vs. ≥ 5 years), and depression assessment time (before vs. after cancer diagnosis).

Review Manager version 5.3 (North Cochrane Center, Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK) was used for data analysis. HR was used as a measure of effectiveness at 95% CI. Based on I2 values, four categories of heterogeneity were established: no heterogeneity (I2 < 25%), low heterogeneity (25% ≤ I2 < 50%), moderate heterogeneity (50% ≤ I2 < 75%), and high heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 75%).

Results

Eligible studies and study characteristics

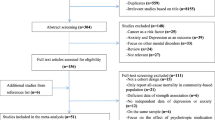

After identifying 2520 references, 575 duplicate publications and 1 876 unrelated studies were excluded, leaving 69 studies that potentially met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, 12 cohort studies conducted between 2013 and 2023 were included in this meta-analysis [2, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17, 21,22,23,24] (Fig. 1).

Table 1 lists the general characteristics of the 12 included studies. These studies included 26,907 patients with CRC, with 302–8961 patients per study. Six prospective studies and 6 retrospective studies. The shortest follow-up time was 1.9 years, whereas the longest follow-up time exceeded 20 years. Among these studies, five studies were from Europe, four were from the USA, two were from Asia, and one was from Australia. Mental symptoms were evaluated in these studies using various tools, such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Epidemiological Research Center for Epileptic Studies Depression Scale, International Classification of Diseases 9, Crown Crisp Index, 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder, and Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form. In most studies, adjustment was performed for variables that affect the risk of cancer death, such as age, tumor stage, and comorbidities. Multivariate analysis was conducted for the adjusted data, whereas univariate analysis was conducted for the unadjusted data.

According to the quality evaluation criteria, ten studies were rated to be of good quality and one study was rated to be of average quality; further, one study could not be evaluated (Table 2).

Impact of anxiety on mortality in patients with CRC

All-cause mortality rate

For the association between anxiety and all-cause mortality, the five studies analyzed in the univariate analysis based on the random effects model yielded a pooled HR of 1.42 (1.02, 1.96), with high heterogeneity (I2 = 78% and P = 0.001; Fig. 2). For the same association, the three studies analyzed in the multivariate analysis based on the random effects model yielded a pooled HR of 0.73 (0.39, 1.36), with high heterogeneity (I2 = 86% and P = 0.0009; Fig. 3).

Univariate analysis revealed that anxiety was associated with a 42% increased risk of all-cause mortality. In contrast, multivariate analysis indicated that anxiety was not associated with the risk of all-cause mortality.

Impact of depression on mortality in patients with CRC

All-cause mortality rate

For the association between depression and all-cause mortality, the five studies analyzed in the univariate analysis based on the fixed effects model yielded a pooled HR of 1.89 (1.68, 2.13), with low heterogeneity (I2 = 26% and P = 0.25; Fig. 4). For the same association, the nine studies analyzed in the multivariate analysis based on the random effects model yielded a pooled HR of 1.62 (1.27, 2.06), with high heterogeneity (I2 = 94% and P < 0.00001; Fig. 5). Univariate analysis revealed that depression was associated with an 89% increased risk of all-cause mortality. However, multivariate analysis indicated that depression was associated with a 62% increased risk of all-cause mortality.

In the multivariate analysis, the mean age of patients in three studies was ≤ 65 years, whereas that in four other studies was > 65 years. Three studies evaluated depression before CRC diagnosis, whereas six studies evaluated it after CRC diagnosis. The follow-up time in five studies was ≥ 5 years, whereas it was < 5 years in four other studies. Subgroup analysis was conducted based on age, time of depression assessment, and follow-up time. The results showed a significant correlation between patients aged ≤ 65 and > 65 years (1.96 (1.29, 3.00) vs. 1.46 (1.16, 1.84)) (Fig. 6(1)). A significant different correlation was observed in patients before and after CRC diagnosis (1.35 (0.99, 1.84) vs. 1.79 (1.30, 2.46)) (Fig. 6(2)). However, no significant difference in risk was noted between studies with a follow-up time of ≥ 5 years (1.46 (1.06, 2.02)) and those with a follow-up time of < 5 years (1.82 (1.40, 2.38)) (Fig. 6(3)).

CRC-specific mortality rate

Three studies were included in the multivariate analysis. Based on the random effects model, the pooled HR for the association between depression and CRC-specific mortality was 1.16 (0.91, 1.48), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 71% and P = 0.03; Fig. 7). Multivariate analysis showed that depression was not associated with the risk of CRC-specific mortality.

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

In accordance with the criteria of the Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, publication bias was not analyzed because none of the groups comprised > 10 studies. However, sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the stability of the results, resulting in the omission of one study from the meta-analysis at a time. The results revealed no significant change in the corresponding merged estimates, indicating that no single study had an impact on the following results: multivariate analysis for the association between anxiety and all-cause mortality, univariate analysis for the association between depression and all-cause mortality, multivariate analysis for the association between depression and all-cause mortality, and multivariate analysis for the association between depression and CRC-specific mortality. However, a significant difference was noted in the results of univariate analysis for the association between anxiety and all-cause mortality. The results of sensitivity analysis are presented in Table 3.

Discussion

Previous studies have confirmed that anxiety and depression are related to cancer mortality; however, to the best of our knowledge, no study has analyzed their relationship with all-cause mortality in patients with CRC [25]. Thus, we performed a meta-analysis to investigate the association of anxiety and depression with CRC along with their predictive factors, but we did not compile or analyze data on mortality [26]. Our meta-analysis is the first study to investigate the predictive value of depression and anxiety on CRC-related mortality. Based on univariate and multivariate data, we conducted a meta-analysis of 26,907 patients and empirically demonstrated that depression and anxiety are associated with an increased risk of mortality in patients with CRC. In these patients, univariate analysis revealed that anxiety predicted a 42% increased risk of mortality, and depression predicted an 89% increased risk of mortality. Multivariate analysis revealed that depression predicted a 62% increased risk of mortality, but anxiety was not associated with an increased risk of mortality. Further, depression was not associated with an increased risk of CRC-specific mortality. Our study results indicate that depression is a more severe risk factor for CRC-specific mortality.

Depression and anxiety can affect the physiological function, treatment compliance, psychological function, and quality of life of patients with CRC, but the extent to the outcome of CRC remains unclear. Researchers have proposed several possible mechanisms, such as lifestyle, behavioral factors, and biological factors, to explain the association of increased mortality with depression and anxiety in patients with CRC. First, individuals with depression and anxiety are more likely to have unhealthy lifestyles, including prolonged sitting, increased alcohol consumption and smoking, poor diet, and obesity [27]. Second, treatment noncompliance is a serious behavioral factor, e.g., low adherence of patients with cancer to medical appointments and treatment [28], which may lead to a poor prognosis. Third, regarding biological factors, a previous showed that depression and anxiety may directly affect endocrine and immune processes [29]. The imbalance of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis may mediate the susceptibility to hormone-related cancer. The activity of natural killer cells and DNA repair enzymes, which play important roles in cancer defense, is inhibited in patients with depression [30]. Further, the distinct effects of depression and anxiety on CRC may be due to their unique mechanisms. Depression manifests as depressive emotions, slow thinking, and loss of interest. In contrast, the characteristics of anxiety are prominent nervousness, worry, and a sense of anxiety. Patients with depression are also more likely to commit suicide than those with anxiety, which may lead to higher all-cause mortality rates.

Our study classified unadjusted and adjusted data as univariate and multivariate data. Considering that the mortality rate of patients with cancer is related to multiple factors, most reported studies have adjusted for demographic and tumor-related variables, such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), tumor stage, and tumor size [11,12,13], whereas other studies have adjusted for anxiety and depression [16]. Regarding anxiety and risk of mortality in patients with CRC, univariate analysis suggested that anxiety is associated with an increased risk of mortality, whereas multivariate analysis suggested no correlation. Meanwhile, regarding depression and risk of mortality in patients with CRC, both univariate and multivariate analyses suggested that depression is associated with an increased risk of mortality. This indicates that depression is a stable predictor.

In multivariate analysis, we conducted subgroup analysis for the association between depression and mortality in terms of age, time of assessment, and follow-up time. The results showed a significant correlation between patients aged ≤ 65 years and those aged > 65 years. A significant different correlation was observed before and after CRC diagnosis. Further, no significant difference in risk was noted between studies with a follow-up time of ≥ 5 years and those with a follow-up time of < 5 years. Our study results showed that younger patients have a higher risk of death than older patients. This finding is consistent with that reported by Wang et al. [31], who analyzed the relationship between breast cancer and depression. However, based on the association between depression and various cancers, Pinquart et al. [32] indicated that the correlation between depression and mortality in older patients is stronger than that in younger patients. Considering that our research focused on CRC, the inconsistency in the results may indicate variation in the mechanisms of mortality due to different cancer types. Furthermore, the survival rate of patients with depression evaluated after cancer diagnosis was worse than that evaluated before cancer diagnosis. We considered that the early diagnosis of depression is associated with early treatment, which is key to improving survival rates. Compared with studies with a follow-up time of > 5 years, short-term follow-up studies reported higher mortality rates, which is consistent with the findings of Watson et al. [33]. This may be because the severity of depression decreases over time [34].

This meta-analysis has certain limitations. First, as mentioned above, the mortality rate of patients with cancer is influenced by various factors, such as age, BMI, tumor stage, and tumor size, which may affect the associations of anxiety and depression with cancer mortality. However, adjustments for different variables were performed in the included studies; therefore, it is not possible to achieve a consolidated association based on consistent adjustment for the same variables. Second, owing to the use of various tools to evaluate depression/anxiety in the included studies, we could not classify depression/anxiety based on different levels or conduct subgroup analysis.

Our research indicates that both depression and anxiety have adverse effects on all-cause mortality in patients with CRC and that depression cannot predict cancer-specific mortality. These findings confirm the importance of early detection and timely treatment of mental disorders in patients with CRC, especially in young patients and those in the early stages of cancer. Our study emphasizes the importance of depression and anxiety in predicting the prognosis of CRC and suggests that routine screening for mental disorders in patients with CRC should be carefully considered.

Data availability

All relevant data are within the paper. We searched the following electronic databases from PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library.

References

Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V, Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Murphy N, Bray F (2023) Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 72(2):338–344. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327736

Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Tworoger SS, Zhang X, Giovannucci EL, Meyerhardt JA, Kubzansky LD (2020) Anxiety, depression, and colorectal cancer survival: results from two prospective cohorts. J Clin Med 9(10):3174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103174

Hansen IO, Jess P (2012) Possible better long-term survival in left versus right-sided colon cancer - a systematic review. Dan Med J 59(6):A4444

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A (2020) Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 70(3):145–164. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21601

Wang YH, Li JQ, Shi JF, Que JY, Liu JJ, Lappin JM, Leung J, Ravindran AV, Chen WQ, Qiao YL, Shi J, Lu L, Bao YP (2020) Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Mol Psychiatry 25(7):1487–1499. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0595-x

Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, Silove D (2014) The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int J Epidemiol 43(2):476–493. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu038

Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, Meader N (2011) Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol 12(2):160–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X

Peng YN, Huang ML, Kao CH (2019) Prevalence of depression and anxiety in colorectal cancer patients: a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(3):411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030411

Cheng V, Oveisi N, McTaggart-Cowan H, Loree JM, Murphy RA, De Vera MA (2022) Colorectal cancer and onset of anxiety and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Oncol (Toronto, Ont.) 29(11):8751–8766. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110689

Kjaer TK, Moustsen-Helms IR, Albieri V, Larsen SB, Degett TH, Tjønneland A, Johansen C, Kjaer SK, Gogenur I, Dalton SO (2021) Risk of pharmacological or hospital treatment for depression in patients with colorectal cancer-associations with pre-cancer lifestyle, comorbidity and clinical factors. Cancers 13(8):1979. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13081979

Lloyd S, Baraghoshi D, Tao R, Garrido-Laguna I, Gilcrease GW 3rd, Whisenant J, Weis JR, Scaife C, Pickron TB, Huang LC, Monroe MM, Abdelaziz S, Fraser AM, Smith KR, Deshmukh V, Newman M, Rowe KG, Snyder J, Samadder NJ, Hashibe M (2019) Mental health disorders are more common in colorectal cancer survivors and associated with decreased overall survival. Am J Clin Oncol 42(4):355–362. https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0000000000000529

Mols F, Husson O, Roukema JA, van de Poll-Franse LV (2013) Depressive symptoms are a risk factor for all-cause mortality: results from a prospective population-based study among 3,080 cancer survivors from the PROFILES registry. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice 7(3):484–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0286-6

Liang X, Hendryx M, Qi L, Lane D, Luo J (2020) Association between prediagnosis depression and mortality among postmenopausal women with colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 15(12):e0244728. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244728

Orive M, Barrio I, Lázaro S, Gonzalez N, Bare M, de Larrea NF, Redondo M, Cortajarena S, Bilbao A, Aguirre U, Sarasqueta C, Quintana JM, REDISSEC-CARESS, CCR group, (2023) Five-year follow-up mortality prognostic index for colorectal patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 38(1):64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-023-04358-0

Xia S, Sun M, Liu X (2020) Major depression but not minor to intermediate depression correlates with unfavorable prognosis in surgical colorectal cancer patients underwent adjuvant chemotherapy. Psychol Health Med 25(3):309–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2019.1643032

Walker J, Magill N, Mulick A, Symeonides S, Gourley C, Toynbee M, van Niekerk M, Burke K, Quartagno M, Frost C, Sharpe M (2020) Different independent associations of depression and anxiety with survival in patients with cancer. J Psychosom Res 138:110218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110218

Rane PB, Madhavan S, Sambamoorthi U, Kalidindi S, Kurian S, Pan X (2014) The impact of pre-existing chronic conditions on cancer diagnosis, receipt of treatment and survival among medicare beneficiaries with colorectal cancer in a rural population. Value Health 17:3(A68-). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.03.398

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int Surg J (London, England) 88:105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson E, Henry DA (2017) AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 358:j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283(15):2008–2012. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

Schofield PE, Stockler MR, Zannino D, Tebbutt NC, Price TJ, Simes RJ, Wong N, Pavlakis N, Ransom D, Moylan E, Underhill C, Wyld D, Burns I, Ward R, Wilcken N, Jefford M (2016) Hope, optimism and survival in a randomised trial of chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 24(1):401–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2792-8

Walker J, Mulick A, Magill N, Symeonides S, Gourley C, Burke K, Belot A, Quartagno M, van Niekerk M, Toynbee M, Frost C, Sharpe M (2021) Major Depression and Survival in People With Cancer. Psychosom Med 83(5):410–416. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000942

Zhou L, Sun H (2021) The longitudinal changes of anxiety and depression, their related risk factors and prognostic value in colorectal cancer survivors: a 36-month follow-up study. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 45(4):101511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinre.2020.07.016

Varela-Moreno, E., Rivas-Ruiz, F., Padilla-Ruiz, M., Alcaide-García, J., Zarcos-Pedrinaci, I., Téllez, T., Fernández-de Larrea-Baz, N., Baré, M., Bilbao, A., Sarasqueta, C., Morales-Suárez-Varela, M. M., Aguirre, U., Quintana, J. M., Redondo, M., & CARESS-CCR Study Group (2022) Influence of depression on survival of colorectal cancer patients drawn from a large prospective cohort. Psychooncology 31(10):1762–1773. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.6018

Wang YH, Li JQ, Shi JF et al (2020) Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Mol Psychiatry 25(7):1487–1499. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0595-x

Cheng V, Oveisi N, McTaggart-Cowan H, Loree JM, Murphy RA, De Vera MA (2022) Colorectal cancer and onset of anxiety and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Oncol 29(11):8751–8766. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110689. Published 15 Nov 2022

Strine TW, Mokdad AH, Dube SR, Balluz LS, Gonzalez O, Berry JT et al (2008) The association of depression and anxiety with obesity and unhealthy behaviors among community-dwelling US adults. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 30:127–137

Kisely S, Crowe E, Lawrence D (2013) Cancer-related mortality in people with mental illness. JAMA Psychiat 70:209–217

Maddock C, Pariante CM (2011) How does stress affect you? An overview of stress, immunity, depression and disease. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 10:153–162

Spiegel D, Giese-Davis J (2003) Depression and cancer: mechanisms and disease progression. Biol Psychiatry 54:269–282

Wang X, Wang N, Zhong L, Wang S, Zheng Y, Yang B, Zhang J, Lin Y, Wang Z (2020) Prognostic value of depression and anxiety on breast cancer recurrence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 282,203 patients. Mol Psychiatry 25(12):3186–3197. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-00865-6

Pinquart M, Duberstein PR (2010) Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 40(11):1797–1810. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709992285

Watson M, Homewood J, Haviland J, Bliss JM (2005) Influence of psychological response on breast cancer survival: 10-year follow-up of a population-based cohort. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 41(12):1710–1714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2005.01.012

Lovibond PF (1998) Long-term stability of depression, anxiety, and stress syndromes. J Abnorm Psychol 107(3):520–526. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.520

Funding

Funding for the construction of key clinical specialties in Futian District, Shenzhen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wenjiang Wu and Shijun Xia conceived and designed this study. Shijun Xia, Yuwen Zhu, and Lidan Luo are responsible for literature retrieval and research selection. Shijun Xia, Linchong Yu, and Lijuan Ma are responsible for data extraction and quality assessment. Statistical analysis was conducted by Shijun Xia, Yuwen Zhu, and Yue Li. Shijun Xia and Wenjiang Wu wrote the first draft of the article. All authors participated in the data interpretation, writing, and correction of the draft paper and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, S., Zhu, Y., Luo, L. et al. Prognostic value of depression and anxiety on colorectal cancer-related mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on univariate and multivariate data. Int J Colorectal Dis 39, 45 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-024-04619-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-024-04619-6