Abstract

Introduction

Total colonic aganglionosis represents a significant challenge for pediatric surgeons. Long-term results are suboptimal and complications are very common. We analyzed our experience to formulate recommendations to achieve better results and avoid complications and sequelae.

Methods

The medical records of patients with total colonic aganglionosis that were operated on by us primarily or secondarily were reviewed. We evaluated: number of operations performed, preventable complications, bowel control or presence of stomas, and clinical follow-up. Based on this experience we describe our current approach for this condition. IRB approval was obtained.

Results

27 patients were identified (19 males, 8 females). 12 patients had the primary pullthrough performed by us and 15 were operated on elsewhere before coming to us for reoperation. The average number of operations per patient was 6.8 (1–40). We identified several preventable complications: ileostomy prolapse or stricture (21), severe diaper rash (10), obstructive symptoms following a pouch or patch-type of pullthrough (9), infection, abscess, and fistula after the pullthrough (5); wrong histologic diagnosis leading to colostomy opening in aganglionic bowel (4) with consequent pullthrough of aganglionic intestine in two of them; anastomotic stricture/acquired atresia (3); and destroyed anal canal and permanent fecal incontinence (2). 15 patients have bowel control; 11 have an ileostomy: temporary (7) and permanent (4); and one is less than 3 years of age. Length of follow-up ranged from 1 to 17 years. Based on this experience, our approach for this condition consists of: colectomy with straight ileoanal anastomosis and ileostomy at presentation, followed by ileostomy closure only when the child is toilet trained for urine and is willing to tolerate rectal irrigations.

Conclusion

Total colonic aganglionosis remains a serious surgical challenge. Patients suffering from the condition, have multiple complications, sequelae, and often require reoperations. We found that it is possible to prevent many of these by properly fixing the stoma, avoiding pouch or patch procedures, delaying ileostomy closure, having pathology expertise, and with meticulous surgical technique starting the dissection/anastomosis well above the dentate line.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Total colonic aganglionosis still represents a challenge for pediatric surgeons. The surgeon’s goal is to provide the patient with a good quality of life that would be reflected in having an acceptable stool frequency, fecal continence, and no symptoms of enterocolitis. There are many operative techniques described [1–6], but it remains unclear which is the ideal procedure to achieve these goals.

Long-term results are suboptimal, complications and sequelae are very common [5, 7–22]. A recent metanalysis did not demonstrate superior results for any type of operation for total colonic aganglionosis. The authors did point out that the most frequent complication in these patients was diarrhea, with or without perineal excoriation [23]. Our approach gives special emphasis to avoid this sequela.

We analyzed our experience with both primary and reoperative cases to formulate recommendations to achieve better results and avoid preventable complications.

Methods

The medical records of patients with total colonic aganglionosis that were operated on by us primarily or secondarily were reviewed. Patients that came to our bowel management program and did not require an operation were excluded from this review. We evaluated: number of operations performed, preventable complications and sequelae, bowel control or presence of stomas, post-operative enterocolitis, and clinical follow-up. Based on this experience we describe our current approach for this condition.

IRB approval was obtained (# 2008-1014).

Results

27 patients were identified (19 males, 8 females). 12 patients had the primary pullthrough performed by us and 15 patients were referred to us for reoperation for a variety of indications after having a primary pullthrough performed elsewhere. The average number of operations per patient was 6.8 (range 1–40).

We identified 54 preventable complications that were divided into seven types (Table 1):

-

(a)

Ileostomy complications (10 patients suffered from 21 ileostomy complications):

-

Prolapse—seven patients required 16 revisions.

-

Stricture—two patients required revision.

-

Inadequate stoma—two patients had their stoma revised due to partial retraction (not matured), and one patient needed stoma revision due to incorrect position of the stoma on the abdominal wall.

-

-

(b)

Severe diaper rash/perianal excoriation (10 patients).

-

(c)

Obstructive symptoms following a pouch/patch pullthrough (9 patients). 7 patients after Duhamel or Duhamel/Martin procedure, 2 patients after J pouch, all of whom suffered from pouchitis.

-

(d)

Infection, abscess, and fistula after the pullthrough (5 patients).

-

(e)

Wrong histologic diagnosis leading to stoma opening in aganglionic bowel (4 patients) with consequent pullthrough of aganglionic intestine in two of them.

-

(f)

Anastomotic stricture/acquired atresia (3 patients).

-

(g)

Destroyed anal canal with consequent fecal incontinence (2 patients).

In terms of bowel function (Table 2): 15 patients have bowel control, 11 have ileostomies: temporary (7) and permanent ileostomies (4), and 1 is less than 3 years of age and is considered too young to be evaluated for bowel control. The length of follow-up ranged from 1 to 17 years.

Five patients out of our 12 primary cases suffered from episodes of enterocolitis after the surgical repair. 10 patients out of 15 patients that required reoperations suffered from enterocolitis at the time they were referred to us.

Associated anomalies were present in four patients: single kidney, ileal atresia, ileal atresia and malrotation, and gastroschisis and malrotation.

One patient had positive family history with his father also having Hirschsprung’s disease.

Based on this experience, our approach for this condition consists of a colectomy with straight ileoanal anastomosis and ileostomy at presentation, putting special emphasis on a meticulous technique aimed at preserving an intact anal canal. Ileostomy closure is performed at a later date, only when the child is toilet trained for urine and is willing to tolerate rectal irrigations. In view of the fact that enterocolitis occurs fairly frequently in patients with total colonic aganglionosis, we are aggressive in treating and teaching parents on how to manage enterocolitis pre and postoperatively with rectal irrigations.

Discussion

We recognize that patients who came to us after a pullthrough was done elsewhere represent a highly biased group of complications that is not necessarily representative of patients operated on for total colonic aganglionosis in other hospitals. But these cases, together with our primary cases, represent the population of patients we were exposed to and we felt that the observations made in this group are valid and worth reporting, especially because in many of them we could identify what we considered to be preventable complications.

Ileostomy prolapse was the most common complication in our series. It can be a serious complication that can result in intestinal loss due to ischemia in patients that cannot afford loosing more bowel. In a previous publication [24] we mentioned our observation indicating that opening a stoma (colostomy or ileostomy) in a non-fixed piece of bowel uniformly results in post-operative prolapse. Ileostomies are, by definition, stomas created in a mobile (non-fixed) portion of the bowel. To avoid prolapse, we recommend fixing the bowel to the anterior abdominal wall, approximately 6–7 cm proximal to the stoma.

When a patient presents to us with significant prolapse, we recommend a surgical repair. Our technique consists of inserting a large amount of packing gauze soaked in povidone-iodine in the prolapsed bowel, and gently reducing it. The abdomen is then palpated to identify the location of the mass that corresponds to the packing gauze inside the bowel, naturally oriented inside the abdomen. A transverse incision is made on top of the palpable mass, usually about 5 cm away from the stoma, opening skin, subcutaneous, muscle, aponeurosis, and peritoneum. The bowel full of gauze is easily identified. The peritoneum and aponeurosis are closed with interrupted vicryl stitches, including a bite of the bowel wall in each stitch (without taking the packing gauze) and securing it to the abdominal wall, which prevents future prolapse. We think this technique is quick, reproducible and free of complications, due to the fact that the stoma itself is left intact, avoiding the risk of local infection.

To avoid stricture of the stoma, it is important to assure adequate blood supply to the bowel. We specifically recommend creating an adequate space to pass the functional bowel through, without being compressed by the fascia. In other words, we avoid creating stomas through a simple stab wound. We rather resect a circle of skin, as well as a circle of aponeurosis, muscle, and peritoneum.

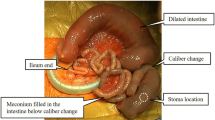

The second most common complication was severe diaper rash/perianal excoriation (Fig. 1). Most of the reported series mention this complication and describe improvement over time (months) as the number of bowel movements decrease, but there is no detailed report on how impaired the quality of life of those patients was while waiting for the improvement to occur. The perianal lesions are as painful and irritating as a second-degree burn. We have been impressed by the severity of the diaper rash that these babies can suffer from. We also believe that the problem has been largely minimized by the pediatric surgical community. Nurses, stoma therapists and of course, mothers, are the ones who suffer together with the babies. We believe that connecting the terminal ileum to the anal canal without an ileostomy in a baby is wrong. Babies and infants subjected to this procedure, even with an intact anal canal and normal sphincters, do not make any attempt to hold the stool. The consequence is multiple bowel movements that result in an intractable diaper rash that gives them a miserable quality of life. In patients with a destroyed anal canal, like two of the patients in our series, the problem is even worse. It is basically equivalent to a perineal ileostomy that does not improve over time, since those patients suffer from fecal incontinence and will need permanent ileostomies.

Based on the observations of those unfortunate babies, we have developed a different management strategy that includes two basic aspects:

-

(a)

To perform an impeccable resection of the colon, as well as an ileo-recto anastomosis 2 cm above the pectinate line to guarantee preservation of the continence mechanism (Figs. 2, 3, 4).

Fig. 3 -

(b)

To keep the ileostomy open until the child is totally toilet trained for urine, and can sit on a potty.

This strategy is frequently rejected by a pediatric surgical community more interested in performing primary procedures as early in life as possible and without a stoma. However, we believe that the quality of life of the baby and their caregivers must be taken into consideration. An open ileostomy allows the baby to grow free of symptoms of enterocolitis and diaper rash.

When the patient is toilet trained for urine, he or she is accustomed to having clean underwear and is capable of verbalizing the desire to use the toilet. Therefore, when the ileostomy is closed, provided the anal canal was preserved, the child will become toilet trained within a few days, as it occurred in our patients.

Besides being toilet trained for urine, we only close the ileostomy if the parents of our patients demonstrate that the child willingly accepts rectal irrigations. This is based on the well-known fact that patients with total colonic aganglionosis have a higher incidence of post-operative enterocolitis, as compared to other types of aganglionosis. Rectal irrigations are the most valuable therapeutic maneuver used to treat enterocolitis and as such, we want to be sure that the child tolerates them, since irrigations are not painful when properly done. To achieve that, we instruct the parents how to perform these irrigations months before the ileostomy closure. Since the child has no diaper rash, and has never experienced painful anorectal maneuvers, they accept the irrigations as a daily routine.

Post-ileostomy closure, we are very pro-active in trying to prevent episodes of enterocolitis. Therefore, we administer Flagyl and start routine rectal irrigations. Every month, assuming the child is doing well, we decrease the amount of Flagyl and the number of irrigations. Usually, it takes about 3 months to discontinue this management. Yet, parents are instructed to perform irrigations every time they suspect enterocolitis or if they think it is necessary.

Based on this experience, we are convinced that, although far from ideal, a direct ileo-recto anastomosis is better than any form of pouch or patch. We recognize the creativity and the rationale that supported the techniques of Martin [1], Duhamel [25], and Kimura [3]. The basic idea was to take advantage of the normal motility of the normoganglionic bowel, combined with the water absorption capacity and lack of peristalsis of a preserved aganglionic segment, to provide a reservoir that would help to form solid stool and that would significantly decrease the number of bowel movements. Unfortunately, as frequently occurs in dealing with a multifactorial biological phenomenon; those techniques gave less than optimal results, as seen in our series. Fecal stasis in the small bowel, particularly in patients with aganglionosis, promotes bacterial proliferation, absorption of toxin, enterocolitis, ulceration and secretory diarrhea, resulting in greater water losses and electrolyte disturbances.

One of the patients that presented with fecal fistula belongs to our primary cases. He was the first patient in our series. At birth we performed an ileostomy and when the patient was 4 years of age we performed a total colectomy and a posterior sagittal approach with ileo-rectal anastomosis without a protective ileostomy. That patient developed a fecal fistula in the midline raphe. In retrospect, we understood that having a midline incision (posterior sagittal approach) attached to a circular anastomosis (ileoanal), located immediately above the sphincter was the perfect set-up for a fistula formation. Currently, we only use the posterior sagittal approach in cases of Hirschsprungs if we are dealing with a case that has suffered multiple previous failed operations and has severe pelvic fibrosis; but we always open a temporary, protective ileostomy.

An error in the histologic diagnosis may lead to complications. Therefore, when discussing the subject of surgical strategy, as determined by suction biopsies, full thickness biopsies and frozen versus permanent sections, one must consider the different local circumstances. Not all institutions have a knowledgeable pediatric pathologist with experience in the histological diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease. Making therapeutic, intraoperative decisions based on frozen sections analyzed by a pathologist without experience is dangerous and may end with catastrophic consequences.

We believe anastomotic stricture/acquired atresia is an avoidable complication due to poor blood supply of the pullthrough bowel. Excessive tension may also contribute to this complication. To avoid this, it is necessary to be familiar with the vascular arcades of the mesentery and the best way to gain bowel length, while preserving the blood supply.

During the operation it is important to avoid damage to the anal canal and sphincters which results in total, permanent fecal incontinence. This occurred in two patients that were referred to us after the pullthrough done elsewhere. To avoid this complication, we use the Lone Star retractor®. The hooks are symmetrically placed in a radial fashion (Fig. 2) and gradually advanced deeper until the rectal mucosa is reached (Fig. 3). In that way, the entire anal canal is folded over and one can guarantee that it is protected. This retractor provides an excellent, immobile operative field that allows for the protection of the mechanism of continence. Traction sutures are applied taking the rectal mucosa 1–2 cm above the dentate (pectinate) line. Special emphasis must be given to work within the available space provided by the retractor, avoiding the unnecessary stretching of the anal canal. Applying uniform traction, a full thickness circumferential dissection is performed until the desired, normoganglionic bowel is reached. At that point, a two layer anastomosis is performed between the normoganglionic ileum and the rectum, 1–2 cm above the pectinate line.

Associated anomalies are infrequent in patients with aganglionosis, but associated gastrointestinal anomalies have an important significance since it can delay the diagnosis of aganglionosis. In this series, two patients that had intestinal atresia had a delayed diagnosis that was only made due to poor post-operative result after the atresia was repaired.

We consider enterocolitis a non-preventable complication; therefore, early in life we teach parents how to detect the signs and symptoms, and how to perform rectal irrigations.

Conclusion

Total colonic aganglionosis remains a serious surgical challenge. Patients suffering from the condition often undergo multiple complications and reoperations. It is possible to prevent many of these complications by properly fixing the stoma, avoiding pouch or patch procedures, delaying ileostomy closure, having pathology expertise available, and using meticulous surgical technique by starting the dissection/anastomosis above the dentate line to preserve the anal canal and sphincters.

References

Martin LW (1968) Surgical management of Hirschsprung’s desease involving the small intestine. Arch Surg 97:183–189

Martin LW (1972) Surgical management of total colonic aganglionosis. Ann Surg 176(3):343–345

Kimura K, Nishijima E, Muraji T et al (1981) A new surgical approach to extensive aganglionosis. J Pediatr Surg 16(6):840–843

Coran AG (1990) A personal experience with 100 consecutive total colectomies and straight ileonal endorectal pull-throughs for benign disease of the colon and rectum in children and adults. Ann Surg 212(3):242–247

Rintala RJ, Lindahl HG (2002) Proctocolectomy and J-pouch ileo-anal anastomosis in children. J Pediatr Surg 37(1):66–70

Lal DR, Nichol PF, Harms BA et al (2004) Ileo-anal S pouch reconstruction in patients with total colonic aganglionosis after failed pull-through procedure. J Pediatr Surg 39(7):E21

Jordan FT, Coran AG, Wesley JR (1981) Modified endorectal procedure for management of long-segment aganglionosis. Ann Surg 194(1):70–75

Polley TZ, Coran AG, Wesley JR (1985) A ten year experience with ninety-two cases of Hirschsprung’s disease including sixty-seven consecutive endorectal pull-through procedures. Ann Surg 202(3):349–354

Bergmeijer JH, Tibboel D, Molenaar JC (1989) Total colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis in the treatment of total colonic aganglionosis: a long term follow-up study of six patients. J Pediatr Surg 24(3):282–285

Levy M, Reynolds M (1992) Morbidity associated with total colon Hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg 27(3):364–367

Hoehner JC, Ein SH, Shandling B et al (1998) Long term morbidity in total colonic aganglionosis. J Pediatr Surg 33(7):961–966

Nishijima E, Kimura K, Tsugawa C et al (1998) The colon patch graft procedure for extensive aganglionosis: long term follow-up. J Pediatr Surg 33(2):215–219

Dodero P, Magillo P, Scarsi PL (2001) Total colectomy and straight ileo-anal Soave endorectal pull-through: personal experience with 42 cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg 11:319–323

Wildhaber BE, Teitelbaum DH, Coran AG (2005) Total colonic Hirschprung’s disease: a 28-year experience. J Pediatr Surg 40:203–207

Escobar MA, Grosfeld JL, West KW et al (2005) Long-term outcomes in total colonic aganglionosis: a 32-year experience. J Pediatr Surg 40:955–961

Anupama B, Zheng S, Xiao X (2007) Ten-year experience in the management of total colonic aganglionosis. J Pediatr Surg 42:1671–1676

Menezes M, Prato AP, Jasonni V et al (2008) Long-term clinical outcome in patients with total colonic aganglionosis: a 31 year review. J Pediatr Surg 43:1696–1699

Barrena S, Andres AM, Burgos L et al (2008) Long-term results of the treatment of total colonic aganglionosis with two different techniques. Eur J Pediatr Surg 18:375–379

Shen C, Song Z, Zheng S et al (2009) A comparison of the effectiveness of the Soave and Martin procedures for the treatment of total colonic aganglionosis. J Pediatr Surg 44:2355–2358

Cheung ST, Tam YH, Chong HM et al (2009) An 18-year experience with total colonic aganglionosis: from staged operations to primaty laparoscopic endorectal pull-through. J Pediatr Surg 44:2352–2354

Mirshemirani AR, Sadeghian S, Kouranloo J (2009) Long-segment aganglionosis: a 15 year experience. Acta Med Iran 47(1):71–74

Rabah R (2010) Total colonic aganglionosis: case report, practical diagnostic approach and pitfalls. Arch Pathol Lab Med 134(10):1467–1473

Marquez TT, Acton RD, Hess DJ et al (2009) Comprehensive review of procedures for total colonic aganglionosis. J Pediatr Surg 44:257–265

Peña A, Migotto-Krieger M, Levitt MA (2006) Colostomy in anorectal malformations: a procedure with serious but preventable complications. J Pediatr Surg 41:748–756

Duhamel B (1957) Technique chirugical infantile. Masson et Eie, Paris

Acknowledgment

We wish to thank Jennifer Hall for her assistance in the editing of the manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bischoff, A., Levitt, M.A. & Peña, A. Total colonic aganglionosis: a surgical challenge. How to avoid complications?. Pediatr Surg Int 27, 1047–1052 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-011-2960-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-011-2960-y