Abstract

Eosinophilic disorders encompass a large spectrum of heterogeneous diseases sharing the presence of elevated numbers of eosinophils in blood and/or tissues. Among these disorders, the role of eosinophils can vary widely, ranging from a modest participation in the disease process to the predominant perpetrator of tissue damage. In many cases, eosinophilic expansion is polyclonal, driven by enhanced production of interleukin-5, mainly by type 2 helper cells (Th2 cells) with a possible contribution of type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s). Among the key steps implicated in the establishment of type 2 immune responses, leukocyte recruitment toward inflamed tissues is particularly relevant. Herein, the contribution of the chemo-attractant molecule thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC/CCL17) to type 2 immunity will be reviewed. The clinical relevance of this chemokine and its target, C-C chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4), will be illustrated in the setting of various eosinophilic disorders. Special emphasis will be put on the potential diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications related to activation of the TARC/CCL17-CCR4 axis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A multitude of conditions are associated with the increased presence of eosinophils in blood and/or tissues, ranging from widespread—and generally benign—disorders such as allergic asthma (AA) or atopic dermatitis (AD) to rare but severe diseases such as myeloproliferative hypereosinophilic syndrome variants (M-HES). The relative contribution of eosinophils to pathogenesis of these disorders is variable, partnering with other immune cell types in the setting of complex interactions (e.g., bullous pemphigoid) or acting as key central effector cells contributing to tissue damage like in PDGFRA/FIP1L1-positive M-HES [1, 2]. Among the factors playing a role in the emergence of eosinophilia, interleukin (IL)-5 is a key cytokine with many effects on this cell throughout its life-span [3]. Sources of IL-5 include type 2 helper T cells (Th2 cells), type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), or malignantly transformed cells, all of which can potentially be involved in the pathophysiology of eosinophilic inflammation and associated diseases [3].

Thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC), also named CCL17, is a CC-chemokine commonly associated with type 2 immune responses [4]. By binding to C-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CCR4), which is, inter alia, expressed by Th2 cells [5], TARC/CCL17 participates in trafficking of Th2 cells in eosinophil-associated disorders including AA and AD and presumably of neoplastic cells in certain T cell lymphomas (e.g., angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma (AITL), mycosis fungoides (MF), and Sezary syndrome (SS)) [6]. Thus, elevated serum and/or tissue levels of TARC/CCL17 and cellular CCR4 expression observed in these disorders may serve as biomarkers correlating with disease severity (e.g., AD [7]) and/or be targeted for therapeutic purposes [8].

Herein, current knowledge on the sources, properties, and functions of TARC/CCL17 and its receptor CCR4 will be reviewed extensively, after a brief overview of type 2 immune responses, eosinophil biology, and the definition and classification of eosinophilic disorders. Their participation in eosinophilic inflammation will be illustrated through preclinical models and clinical findings. Finally, we will discuss to which extent the TARC/CCL17-CCR4 axis can serve as a diagnostic or prognostic marker and/or as a therapeutic target in human eosinophilic diseases.

General considerations about type 2 immune responses and eosinophil biology

Type 2 immune cells typically participate in host defense against helminths and are the hallmark of the so-called allergic reaction in which genetically predisposed individuals develop immediate hypersensitivity in response to an antigen, called an allergen, after repeated exposures [9]. As a consequence of decreased epithelial barrier integrity, for example following direct trauma, viral infection, or a genetic defect, the immune system may encounter environmental allergens (e.g., peptides derived from pollen or house dust mite (HDM)) [9]. By secreting alarmins, including IL-25, IL-33, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), damaged epithelial cells activate ILC2s, the innate non antigen-receptor-expressing counterpart of Th2 [10]. These cells act as a primary source of type 2 cytokines through expression of the transcription factor GATA-3 [10], thereby initiating type 2 responses by recruiting other innate cells (including eosinophils) and promoting Th2 differentiation [11].

Activation and differentiation of naïve CD4 T cells into IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 producing Th2 cells is a key step in the generation of type 2 immune responses. The underlying mechanisms are complex, mainly involving IL-4-dependent activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription(STAT)6 that leads to the expression of GATA-3 which in turn collaborates with STAT5 to drive the expression of IL-4 from the shared IL4-IL13 gene within the T cell itself [12, 13]. Once activated, Th2 cells migrate to sites of antigen/allergen exposure and accomplish their effector functions. This recruitment to inflamed tissue involves selective expression of integrins, selectins, and chemokine receptors depending on their state of activation and differentiation [4]. For example, circulating CCR8+ CD4 T cells from healthy humans produce more IL-5 (a characteristic of highly differentiated Th2 cells) than CCR4+ CD4 T cells in which IL-4 is predominant [14]. Other chemoattractant factors for human and murine Th2 cells include IL-33, CCL17, CCL18, CCL20, CCL22, CXCL10, CX3CL1, leukotriene B4, and prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) [4, 15].

The effector functions of Th2 cells in tissue are largely mediated by the canonical type 2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 which orchestrate the early and late phases of allergic disease. Interleukin-4 favors isotype class-switching within allergen-specific B cells, leading to production of IgE-type immunoglobulins. By binding to the FcεRI expressed on mast cells and basophils, allergen-specific IgE induces degranulation and release of an array of mediators that account for the typical manifestations of allergic reactions [9]. Interleukin-13 induces goblet cell hyperplasia, mucus secretion, smooth muscle contraction, and subepithelial fibrosis [16].

Interleukin-5 is critically involved in the constitution of eosinophilic inflammation. In healthy humans, eosinophils account for 3–5% of blood leucocytes and are easily recognizable by their bilobed nucleus and their cytoplasmic eosin-avid granules. They originate in the bone marrow (BM), where common myeloid progenitors give rise to eosinophilic progenitors (hEoP) characterized by surface expression of the IL-5 receptor alpha chain (IL-5Rα, CD125) that will be preserved throughout their life-cycle [17]. Human EoP will become mature eosinophils through mechanisms relying on the expression of several transcription factors (GATA-1, C/EBPα, C/EBPε, and PU-1) and growth factors including IL-5, IL-3, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) [18, 19].

Eosinophils are the predominant cell type in humans and mice expressing the IL-5 receptor at high levels, explaining the high specificity of IL-5 for this cell-type. Interleukin-5 forms homodimers that bind to the IL-5Rα chain which is coupled with the signal-transducing common beta chain [3]. Effects of IL-5 include eosinophil development through proliferation, differentiation, and maturation of hEoPs; egress of mature eosinophils from bone marrow; homing and activation in inflamed tissue; and inhibition of peripheral apoptosis [3]. ILC2s represent an important source of IL-5 in homeostatic conditions, supporting for example the colonization of the small intestine and visceral adipose tissue by eosinophils in mice [20, 21]. In pathological situations however, IL-5 derives from Th2 cells and mast cells, in addition to ILC2s [3].

Eosinophil trafficking can be independent of IL-5 as demonstrated by the presence of eosinophils in tissues from IL-5-deficient mice [22]. Several chemokines collectively called eotaxins (eotaxin-1 (CCL11), eotaxin-2 (CCL24), and eotaxin-3 (CCL26)) bind to eosinophil-expressed CCR3 and are key factors in eosinophil chemotaxis, both in homeostatic (CCL11) [23] and inflammatory (CCL24 and CCL26) conditions [24]. Cellular sources of eotaxins include epithelial cells, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, chondrocytes, and macrophages, and their synthesis is dependent on IL-4 and IL-13 [25, 26]. VCAM-1/VLA4 [27], PGD2/chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on Th2 cells (CRTH2) [28,29,30], and TSLP/TSLPR [31] interactions are also involved in eosinophil recruitment. The contribution of the TARC/CCL17-CCR4 axis in eosinophil trafficking remains debated, as CCR4 expression by blood and/or lung/bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) eosinophils has been observed in mice and humans in some [32, 33] but not all studies [34,35,36,37,38].

When engaged in an inflammatory response, eosinophils display a series of effector functions that are largely mediated by pre-formed mediators localized in so-called primary and specific (or crystalloid) granules and in lipid bodies. These mediators, which have been extensively described elsewhere [39], together with reactive oxygen species and IgE antibody–dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) contribute to host defense against helminths and ectoparasites, even if in vivo data are scarce in humans and divergent in mouse [19]. Furthermore, these effector functions account for eosinophil-mediated cytotoxicity and fibrosis, pro- and anti-inflammatory effects, and antiviral activity to name a few [40] and may cause significant damage in surrounding tissue.

Eosinophilic disease

Eosinophilic disorders encompass a wide range of diseases, from frequent and benign to rare and severe, which are characterized by increased blood and/or tissue eosinophilia associated with variable degrees of eosinophil-mediated damage. Indeed, eosinophil activation and degranulation can result in major, potentially irreversible or lethal organ dysfunction and damage. The archetype of eosinophil-induced toxicity is endomyocardial inflammation favoring formation of mural thrombi and subendocardial fibrosis that may progress to restrictive heart failure. Other deleterious consequences of sustained eosinophilia can occur in all organs including most commonly the skin, lungs, central and peripheral nervous systems, digestive tract, and connective tissue [41].

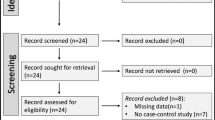

The definition and classification of eosinophilic disorders were revisited in 2011 by the “International Cooperative Working Group on Eosinophil Disorders” (ICOG-EO), more than 35 years after the first formal elaboration of criteria defining the hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) [42, 43]. Eosinophilia is defined as an absolute blood eosinophil count (AEC) above 0.5×109/L, while the term hypereosinophilia (HE) applies when an AEC above 1.5×109/L is observed at least twice, with an interval of at least 1 month. In tissue, HE is present when (1) the percentage of eosinophils in BM exceeds 20% of all nucleated cells and/or (2) a pathologist considers that tissue infiltration by eosinophils is excessive and/or (3) marked deposition of eosinophil granule proteins is found. The term HES is reserved for patients fulfilling the criteria for blood and/or tissue HE and presenting with organ damage and/or dysfunction attributable to eosinophils, after exclusion of other disorders or conditions as potential cause(s) of the observed organ damage [42].

Hypereosinophilia can be further classified into variants [42]: proliferation of eosinophils may be clonal and is qualified as neoplastic (HEN), whereas polyclonal expansion of eosinophils driven by enhanced production of growth factors (mainly IL-5) is qualified as reactive (HER). When the mechanism underlying increased eosinophilopoiesis is unknown and no organ dysfunction or symptoms are present, the term HE of undetermined significance (HEUS) applies. Rarely, HE can be detected in several members of a same family and is inherited, defining familial HE.

The first step in the diagnostic approach to eosinophilia or HE is to rule out a reactive/secondary cause [44], such as allergic disease (e.g., severe eosinophilic asthma), parasitosis (e.g., helminths, scabies), adverse drug reactions (e.g., anticonvulsants), and cancer (e.g., certain adenocarcinomas, Hodgkin’s or T cell lymphomas). The second step is to assess for potential eosinophil-induced organ damage. If present, diagnosis of HES must be considered, and further evaluation for HES disease variants is warranted. Neoplastic (HESN, or primary, clonal, myeloproliferative) HES is associated in approximately 80% of cases with a deletion on chromosome 4q12, creating the Fip 1-like 1 (FIP1L1)/platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) fusion gene, which encodes a constitutively active tyrosine kinase (TK) [45]. Reactive (HESR, or secondary) HES describes situations where reactive HE causes organ damage and dysfunction. Besides classical causes of secondary HE (see above), this entity encompasses lymphocytic variant HES (L-HES) where HE is caused by enhanced IL-5 production by a clonal T cell subset with an abnormal surface phenotype [46]. Finally, the term idiopathic HES (I-HES) is used when the diagnostic work-up fails to identify a known etiology for eosinophilic expansion. This last category accounts for more than half of patients presenting with HES in expert centers [47].

The biology of thymus and activation-regulated chemokine

TARC/CCL17: early discoveries, cellular expression, and mechanisms of synthesis

With the discovery of TARC/CCL17 in 1996, Imai et al. were the first to describe a CC chemokine with selective activity for lymphocytes [48]. Its name reflects the observed constitutive expression in the human thymus and its induction in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) following activation by phytohemagglutinin [48]. One year later, the same team identified CCR4 as the main receptor for TARC/CCL17 and showed that CCR4 mRNA was expressed in CD4+ T cells [49].

Human TARC/CCL17 is an 8-kDa protein composed of 71 amino acids and is encoded on chromosome 16q13 [48, 50]. Murine studies have shown that steady-state TARC/CCL17 synthesis occurs in various tissues including the thymus, lymph nodes (LNs), gut, and bronchi but not in the spleen. The cellular sources of this chemokine were mainly Langerhans cells (LCs) and mature myeloid dendritic cells (DCs) [51]. In humans, monocyte-derived DCs were shown to synthetize TARC/CCL17 in response to IL-3 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in presence of IL-4 in in vitro cultures [5]. Subsequently, several immune and non-immune cellular sources of TARC/CCL17 were identified, as detailed in Table 1.

Molecular mechanisms underlying TARC/CCL17 synthesis and secretion are variable depending on the nature of the cell and the stimuli. In immune cells, IL-4 stimulates TARC/CCL17 synthesis, synergizing with other cytokines depending on the cell type [5, 52,53,54]. STAT6 activation is a key step in IL-4-induced TARC/CCL17 synthesis by binding directly to the CCL17 gene promoter via two binding sites (Fig. 1) [55]. In keratinocytes and bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells, TARC/CCL17 synthesis is triggered by TNF-α and interferon (IFN)-γ that act synergistically in a nuclear factor-kappa B (NFκB)-dependent manner [56,57,58], consistent with the presence of a NFκB binding site in the CCL17 promoter [59]. The effect of IL-4 varies, with an inhibitory effect observed in keratinocytes [56, 60] while a co-stimulatory effect applies to other cell types (Table 1).

Identified molecular mechanisms underlying TARC/CCL17 synthesis in selected cell types. Mechanisms involved in induction of TARC/CCL17 synthesis are shown schematically for a human keratinocyte cell lines (HaCaT) and b human monocytes and murine bone marrow–derived macrophages. In HaCaT cells, TNF-α and IFN-γ induce JAK2, p38 MAPK, and Raf-1 activation by phosphorylation after ligation to their dedicated receptors [168, 170]. Subsequently, activated p38 MAPK phosphorylates STAT1 and NFκB, inducing their activation and translocation into the nucleus to trigger TARC/CCL17 synthesis [169]. b In human monocytes and murine macrophages, IL-4 and IL-13-induced phosphorylation and homodimerization of STAT6 (following engagement of both types of IL-4 receptors) triggers TARC/CCL17 expression directly by binding the TARC gene promoter [53, 206]. In addition, activated STAT6 increases transcription of IRF4 and JMJD3, and the latter induces the demethylation of repressive H3K27me3 in the IRF4 promoter region, resulting in enhanced expression of the transcription factor IRF4 that binds directly to the TARC/CCL17 promoter (*the latter mechanism is demonstrated after IL-4 but not IL-13-induction of STAT6) [53]. A similar pathway is involved in GM-CSF-induced TARC/CCL17 transcription, probably through STAT5 activation [52]. Engagement of the type 1 IL-4Rα/common-γ chain heterodimeric receptor by IL-4 also recruits IRS2, inducing its phosphorylation and activation. In turn, IRS2 phosphorylates/activates the PI3K/AKT pathway, ultimately leading to TARC/CCL17 transcription [206]. SOCS1 expression is also induced by IL-4 in healthy human monocytes and has been shown to interact directly with IRS2 and downregulate its activity, through ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [206]. This figure was created with BioRender.com. IFN interferon, IL interleukin, IRF interferon regulatory factor, IRS insulin receptor substrate, JAK Janus kinase, JMJD3 Jumonji domain-containing protein D3, MAPK mitogen-activated protein kinases, NFκB nuclear factor-kappa B, PI3K phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, STAT signal transducer and activator of transcription, SOCS suppressor of cytokine signaling protein, TNF tumor necrosis factor, TYK tyrosine kinase

TARC/CCL17 selectively binds to CCR4

CCR4 belongs to the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family and is thus composed of seven transmembrane domains [61]. In addition to TARC/CCL17, CCR4 binds macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC/CCL22) which shares 37% homology in its amino acid sequence [6]. MDC/CCL22 is also expressed in the human thymus [62] and produced by DC, macrophages, and monocytes [63,64,65]. MDC/CCL22 exhibits 2- to 3-times higher affinity for CCR4 compared with TARC/CCL17 [62] and is more potent in promoting integrin-dependent arrest of lymphocytes on VCAM-1 [66] as well as inducing CCR4 desensitization and internalization [67]. These differences may be explained by different CCR4 conformations. In human T cells, the major R1 form binds both chemokines while the minor R2 forms only bind MDC/CCL22. When all R1 receptors are occupied, MDC/CCL22 is still able to increase chemotaxis through R2 receptors whereas an additive effect of TARC/CCL17 is not possible [68]. Furthermore, GPCR-induced chemoattraction by MDC/CCL22 of in vitro differentiated murine Th2 cells was shown to rely not only on the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway (shared with TARC/CCL17) but also on beta-arrestin-2, enhancing chemotaxis [69]. Whether the activation of this pathway by MDC/CCL22 is linked to a distinct CCR4 conformation is not known.

Functional characterization of CCR4-expressing CD4+ T cells supports their Th2 differentiation as they spontaneously synthetize IL-4 and IL-5 but no IFN-γ in in vitro cultures [5]. These early discoveries suggested a potential role of TARC/CCL17 and CCR4-expressing cells in type 2 immune responses as discussed below. Besides Th2 cells, several other cell types involved in type 2 immune responses express CCR4, including ILC2s [70]. Other populations reported to be CCR4-positive are listed in Table 2.

TARC and its relevance in eosinophilic diseases

Several studies have shown that TARC/CCL17 may be increased in serum and/or tissues in various eosinophilic conditions. These findings are summarized in Table 3 and described in more detail below.

Skin disorders

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by upregulation of Th2 and Th22 cytokines in the acute phase, while a Th1 and Th17 profile has been demonstrated by gene expression studies in chronic lesions [71]. A type 2 immune response is central in the pathogenesis of AD, with production of allergen-specific IgE-type antibodies [71]. Eosinophilia is common in blood and skin in this disorder, but is not likely to play a central role in established lesions, as suggested by the lack of clear-cut efficacy of the anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody (MoAb) mepolizumab in clinical trials [72, 73].

TARC/CCL17 is expressed in both acute and chronic lesions of AD by epidermal keratinocytes, dermal-infiltrating cells (CD3+ T cells and CD1a+ DC), and endothelial cells, while it is absent in normal skin [74]. Consequently, higher levels of serum (s)TARC/CCL17 are observed in AD compared to healthy controls (HC) [74]. Their levels correlate with AEC and weakly with sIL-2R-alpha (sCD25) levels, a known biomarker of T cell activation in vivo [75, 76]. T cells expressing CCR4 are detectable in lesional skin at the dermoepidermal junction, and the proportion of circulating CD4+CD45RO+ cells expressing CCR4 is higher in patients with AD compared to HC [75]. Of note, in AD, most of the circulating CCR4+ T cells were also positive for cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA) in two other studies [77, 78].

The contribution of the TARC/CCL17-CCR4 axis to AD pathogenesis involves several mechanisms. We previously mentioned the importance of TNF-α and IFN-γ in TARC/CCL17 synthesis by the keratinocyte cell line HaCaT and its repression by IL-4. Furthermore, in vitro cultured peripheral T cells from HC produce IL-22, TNF-α, and IFN-γ in response to HDM extracts, whereas HaCaT cells upregulate IL-22Rα at their surface. Activation of the IL-22/IL-22Rα axis leads to production of TARC/CCL17, IL-1α, and IL-6 by HaCaT cells and recruitment of CCR4+ T cells [79]. Finally, regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells (Treg) are known to express CCR4 and display higher expression levels in patients with severe AD compared to HC combined with a reduced ability to secrete transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and IL-10 and to suppress autologous effector T cells in vitro, indicating the probable recruitment of functionally impaired Tregs into AD skin [80].

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) is a severe drug reaction associating a disseminated rash, fever, eosinophilia, atypical circulating lymphocytes, lymphadenopathy, and organ dysfunction [81]. Serum TARC/CCL17 levels may be extremely elevated in this disorder, and CD11c+ DC have been shown to be the main source in lesional skin [82]. The level of sTARC/CCL17 correlates positively with the severity of skin manifestations as well as AEC and sCD25 [82] and is significantly higher in patients with demonstrated HHV-6 reactivation [83], although the causal link between viral reactivation and TARC/CCL17 over-expression remains elusive. Some argue that increased TARC/CCL17 could attract Tregs and alter antiviral responses leading to HHV-6 reactivation or, alternatively, TARC/CCL17 could directly induce HHV-6 activation through the chemokine receptor homologues of HHV-6 [83, 84].

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune blistering disease characterized by autoantibodies targeting hemidesmosomes and is often accompanied by blood eosinophilia, elevated serum IgE levels, and a dermal infiltrate mainly composed of lymphocytes and eosinophils [1]. Several lymphocyte subsets seem implicated in BP including Th2 and Th17 cells [1]. Eosinophils are thought to play a pathogenic role since their degranulation is induced by FcεRI engagement by anti-basement membrane IgE, leading to blister formation in a humanized mouse model of BP [85]. Elevated TARC/CCL17 levels have been found in blister fluid and serum from patients with BP, and this chemokine was detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in basal epidermal keratinocytes from lesional skin of BP patients while CCR4 was expressed by dermal CD4+ and peripheral blood CD4+CD45RO+ T cells [86].

Senile erythroderma

Erythroderma is a debilitating skin disease defined as more than 90% of skin surface affected by erythema and scaling. More than a quarter of patients with erythroderma have peripheral eosinophilia [87]. Erythroderma may be idiopathic or secondary, occurring in the setting of disorders such as psoriasis, atopy, drug hypersensitivity (including DRESS), MF, or SS, most of which are associated with elevated sTARC/CCL17. In one series of 68 patients with erythroderma aged 65 years or older, of which 53% had a detectable secondary cause, sTARC/CCL17, serum IgE, and the level of blood and tissue eosinophilia did not differ between idiopathic and secondary subgroups [88]. Interestingly, patients with senile erythroderma (predominantly male in this study) had lower IgE levels and a lower ratio of antigen-specific IgE/total IgE but higher levels of sTARC/CCL17 than patients with AD suggesting that IgE synthesis in this disorder is the consequence of a Th2 shift independent of specific allergens [88, 89].

Other skin disorders

Elevated sTARC/CCL17 levels have been reported sporadically in several other dermatological disorders, namely, eosinophilic pustular folliculitis [90], chronic spontaneous urticaria [91], maculopapular exanthema [92], and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (although levels are significantly lower than in DRESS) [93]. Patients with non-episodic angioedema with eosinophilia were shown to have elevated sTARC/CCL17 levels at presentation that regressed in parallel with AEC in response to corticosteroid (CS) therapy in one study [94]. In episodic angioedema, serum TARC levels are also elevated and cycle with disease activity as discussed below [95].

Pulmonary disorders

Allergic asthma (AA) is a chronic respiratory disease often characterized by eosinophilic inflammation of the airways together with increased mucus secretion and bronchial hyperreactivity. The underlying type 2 immune response combines ILC2s that represent an early source of type 2 cytokines after allergen challenge and Th2 cells [96]. Consistent with the key role of eosinophils in a subgroup of patients, biologics targeting IL-5 and its receptor reduce exacerbations and improve lung function in severe eosinophilic asthma and have been approved as add-on therapies in this indication [97].

The TARC/CCL17-CCR4 axis has been well studied in asthma, since it contributes at least partially to Th2 cell recruitment to the lung. Ex vivo allergen challenge of human bronchial explants has been shown to induce synthesis of functionally active TARC/CCL17 in patients with asthma but not HC [98]. Furthermore, several studies in asthmatic patients have reported induction of TARC/CCL17 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) after allergen challenge [99, 100]. Cellular sources of TARC/CCL17 in this context include not only bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells [57, 58, 101] but also CD11c+ DCs [102], M2 macrophages [103], and CD4+CD45RA+ T cells [104]. Eosinophils themselves are a potential source of TARC/CCL17 and MDC/CCL22 as demonstrated in a mouse model of allergic airway inflammation [105] and after in vitro stimulation with different cytokines in humans [106]. Altogether, these data indicate that TARC/CCL17 may contribute to effector T cell chemotaxis to lungs in asthma. Although it has been shown that CCR4+ T cells are the main source of type 2 cytokines in asthmatic patients [98], the functional relevance of the TARC/CCL17-CCR4 axis in AA remains to be elucidated, as targeting this pathway in animal models has produced conflicting results with regard to the consequences on airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation [102, 107,108,109,110].

Other airway disorders

Patients with allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) were reported to have higher TARC/CCL17 levels in nasal secretions than patients with non-allergic, non-infectious rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps, and higher sTARC/CCL17 than HC [111]. Elevated sTARC/CCL17 levels have also been observed in patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) both in the setting of cystic fibrosis (CF) and AA [112]. In patients with CF, a positive correlation was observed with A. fumigatus-specific IgE [112].

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, formerly Churg-Strauss syndrome) is a rare granulomatous, eosinophil-rich, necrotizing vasculitis affecting small- and medium-sized vessels and associated with late-onset asthma and eosinophilia [113]. In 30–40% of cases, EGPA is associated with antineutrophil-cytoplasmic-antibodies (ANCAs) [114]. The pathogenesis of EGPA is complex, involving type 2 immunity, B cell activation with antibody production, and Th17 cells [114]. Patients with EGPA often have a history of allergic disease and high serum IgE levels [114]. TARC/CCL17 is expressed in active EGPA lesions in association with eosinophilic infiltrates, colocalizes with CRTH2+ T cells, and elevated serum levels have been reported in several studies [115,116,117]. sTARC/CCL17 has been shown to correlate with disease activity, AEC, and serum IgE levels in this disease [115].

Acute and chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP and CEP) are characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of the lung parenchyma, and the former may progress to an acute respiratory distress syndrome in some cases [118]. Blood eosinophil counts are generally within normal ranges at diagnosis of AEP while they are increased in 80% of patients with CEP [118]. Elevated levels of type 2 cytokines and TARC/CCL17 in BALF have been reported in both disorders [119]. There was a tendency toward higher TARC/CCL17 levels in AEP, and a positive correlation was observed with IL-5 and IL-13 in this disorder [119]. Similarly, sTARC/CCL17 levels were significantly higher in AEP than in sarcoidosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and interstitial pulmonary fibrosis [119]. A challenge with the suspected trigger of AEP in two patients was followed by a rise in sTARC/CCL17 within 16 h after provocation [120]. Cellular sources of TARC/CCL17 identified in AEP comprise alveolar DC and macrophages [121]. CCR4-positive CD4+ T cells were significantly higher in BALF than in blood in patients with AEP and CEP and were not observed in BALF from HC or patients with sarcoidosis [122]; their numbers correlated positively with BALF TARC/CCL17, MDC/CCL22, and IL-5 [122]. Ultimately, transendothelial migration of eosinophils in response to BALF from patients with AEP, assessed in vitro using human pulmonary microvascular cells, was not abrogated by a CCR4 antagonist in vitro [123]. Together, these findings highlight the increased presence and probable role of the CCR4/CCL17 axis in T cell chemotaxis to the lungs in AEP, but other factors may contribute to eosinophil accumulation.

Lymphoproliferative malignancies

Mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sezary syndrome (SS) belong to the spectrum of cutaneous T cell lymphoma and are characterized by clonal proliferation of mature T cells in the skin [124]. Disease course in MF is progressive while SS is more aggressive and generally combines circulating neoplastic T cells, erythroderma, and lymphadenopathy [125]. As disease progresses, the cytokine profile in MF evolves from type 1 to type 2, while SS typically displays only a type 2 profile where cytokine levels correlate with blood eosinophilia and serum IgE [125]. The atypical lymphoid cells that characterize this disease spectrum have hyperchromatic cerebriform nuclei, they can be detected in peripheral blood, and their distribution within tissue depends on the disease stage [125, 126]. These cells typically express CLA and CCR4 at their surface, while TARC/CCL17 is present within keratinocytes in affected skin [74]. sTARC/CCL17 levels are elevated in all disease stages but are significantly higher in advanced (tumor) stage MF and in SS [127, 128].

Expression of CCR4 may be observed in other T cell malignancies as well, such as angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma (AITL), unspecified peripheral T cell lymphoma (PTCL-U), and adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) [129]. TARC/CCL17 was detected by IHC in lymph nodes from patients with AITL and PTCL-U within cells with dendritic morphology, and its expression level correlated with eosinophilic infiltration in lymphomatous tissue [130]. Elevated TARC/CCL17, MDC/CCL22, and CCR4 mRNA expression was reported in skin from patients with ATLL compared with HC [131]. In vitro chemotaxis assays showing that the CCR4+ malignant T cells isolated from peripheral blood of ATL patients respond strongly to TARC/CCL17 and MDC/CCL22 indicate that this axis plays a functional role in pathogenesis of this disorder [131].

Hypereosinophilic syndromes

Lymphocytic variant HES (L-HES) is an indolent T cell lymphoproliferative disorder in which the clonal cells display an abnormal surface phenotype (most often CD3-CD4+TCRα/β-) and produce type 2 cytokines including IL-5 [132], explaining its classification as HESR. Common clinical manifestations include skin lesions, angioedema, lymphadenopathy, and rheumatological involvement [133, 134]. In a study investigating chemokine receptor expression on these naturally occurring human Th2 cells, our group showed that CD3−CD4+ cells expressed CCR5, CXCR4, and CCR4, although the latter was observed only when cells were left in autologous serum-free milieu suggesting that CCR4 was internalized in vivo [135]. Measurement of its ligands TARC/CCL17 and MDC/CCL22 in serum from subjects with CD3-CD4+ L-HES confirmed that sTARC/CCL17, but not sMDC/CCL22, levels were markedly elevated compared to controls, a finding that was subsequently observed in L-HES patients with other phenotypically aberrant T cell subsets as well [135, 136]. Cellular sources of TARC/CCL17 have not yet been explored in vivo, but it was shown in vitro that IL-4 issued from CD3−CD4+ cells can stimulate its production by DC, but not by eosinophils or T cells [135]. A subset of patients with CD3-CD4+ L-HES present clinically with Gleich’s syndrome, also known as episodic angioedema with eosinophilia. One study has shown that serum IL-5 and sTARC/CCL17 peak prior to blood eosinophilia and symptoms in such patients, suggesting an early role for this chemokine in the cascade of events leading to a flare [95].

Besides those with well-documented L-HES, a subset of patients with I-HES have higher sTARC/CCL17 levels than HC. One study showed that PBMC isolated from these patients display some degree of spontaneous IL-5 production in vitro, contrasting with I-HES patients with normal sTARC/CCL17 levels [136]. The proportion of I-HES patients with above-normal sTARC/CCL17 levels reached 36% in a large retrospective multicentric study, although the geometric mean was lower than in patients with L-HES (3406 vs 12,979 pg/mL respectively, p=0.02) [137].

Clinical implications

Activation of the TARC/CCL17-CCR4 axis, as reflected by elevated sTARC/CCL17 levels, may provide clues to the differential diagnosis of certain inflammatory disorders, predict disease severity, and/or help monitor disease activity (Table 3). In certain instances, this axis plays a pathogenic role, either because TARC/CCL17 is a key factor eliciting inflammation or because aberrant cells that drive pathogenesis express CCR4, and therefore represents a potential therapeutic target.

TARC as a biomarker for diagnosis, disease activity, and prediction of disease severity and treatment responses

Atopic dermatitis

In AD patients, an early study showed that sTARC/CCL17 correlated with disease activity (assessed by Scoring AD index, SCORAD) and AEC [75]. A prospective study conducted on a large cohort (n=320) of adults with AD highlighted the accuracy of sTARC/CCL17 to monitor disease severity given the positive relationship between this chemokine and clinical skin scores [7]. Moreover, elevated sTARC/CCL17 at presentation could also predict a more severe course, although this remains to be firmly established given some observed heterogeneity in results so far [7].

DRESS

In patients with severe drug reactions, elevated sTARC/CCL17 has been shown to be a discriminating factor for diagnosis of DRESS rather than Steven-Johnson syndrome and maculopapular erythema [83]. In patients with DRESS, sTARC/CCL17 correlates with the severity of skin manifestations at onset and decreases together with skin healing and normalization of serum IL-5 [82].

Bullous pemphigoid

A positive correlation has been observed between AEC and sTARC/CCL17 as well as disease activity, indirectly suggesting that sTARC/CCL17 could also correlate with disease activity [86]. In this line, sTARC/CCL17 levels were shown to correlate with the BP Disease Area Index score as well as urticaria/erythema scores in a series of 20 BP patients [138]. Serum TARC/CCL17 may actually be a better marker of disease activity than anti-BP180 autoantibodies, as fluctuations occurred earlier in patients experiencing disease flares in a recent study [138].

Senile erythroderma

Although a positive correlation has been observed between IgE and sTARC/CCL17 in patients with both idiopathic and secondary senile erythroderma [88], sTARC/CCL17 was more markedly elevated in patients with chronic idiopathic erythroderma (predominantly male) in one study, leading the authors to propose the use of a sTARC/IgE ratio to distinguish this patient sub-group from elderly patients with AD, showing a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 95% when the ratio is superior to 7.24 [89].

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

TARC/CCL17 was an independent predictive biomarker for the rapid decline in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) in stable patients with COPD [139].

EGPA

sTARC/CCL17 is elevated in EGPA and correlates with disease activity [115]. Unfortunately, neither eotaxin-3/CCL26 nor TARC/CCL17 had sufficient accuracy for relapse-prediction in previously treated patients [116]. In addition, neither chemokine was useful to distinguish patients with ANCA-negative EGPA from those with HES presenting with a history of asthma and sinusitis [117].

ABPA

sTARC/CCL17 was shown to be more reliable than total IgE and A. fumigatus-specific IgE in serum for the diagnosis of ABPA in patients with CF and helped discriminate this condition from simple colonization or sensitization to A. fumigatus where levels are normal [112]. In addition, the rise in sTARC/CCL17 precedes that of IgE during disease development, offering the potential for early detection and management of this debilitating condition [140]. Higher sTARC/CCL17 levels may predict more severe disease as the levels of this chemokine correlated negatively with lung function in CF patients with ABPA [112].

Acute eosinophilic pneumonia

In patients with acute lung injury (ALI), sTARC/CCL17 levels accurately differentiate patients with severe forms of AEP from those with acute interstitial pneumonia, pneumonia-associated ALI/ARDS, and patients with alveolar hemorrhage. In fact, among several candidate biomarkers (including eotaxin-1/CCL11, Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6) and surfactant protein-D), sTARC/CCL17 had the largest AUC (1.00, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.00) with a concentration threshold from 6259 to 7040 pg/mL [120]. Furthermore, sTARC/CCL17 levels correlated with those in BALF during active disease and decreased in parallel with regression of symptoms [120].

T cell lymphoma

In MF and SS, CCR4+ cell numbers increase in parallel with disease progression [128], and higher expression of CCR3 and CCR4 by lymphomatous cells in skin samples is associated with poor survival [141]. In MF, sTARC/CCL17 were significantly higher in tumor stage than in patch or plaque stage [127]. CCR4 expression by malignant cells is also associated with a poor prognosis in patients with ATLL and PTCL-U [129, 142].

Hypereosinophilic syndrome

In patients presenting with persistent unexplained HE, markedly elevated sTARC/CCL17 levels are associated with L-HES whereas normal values are observed in patients with no evidence for underlying Th2-driven pathogenesis [136]. In a recent study on a large cohort of HES patients, our group determined that a threshold value of 3000 pg/ml should raise suspicion of L-HES [143] although similarly elevated levels were also observed in patients with I-HES presenting clinically as eosinophilic dermatitis. A rise in sTARC/CCL17 could also be an early marker heralding a disease flare in patients with episodic angioedema with eosinophilia associated with CD3-CD4+ T cells [95].

Furthermore, sTARC/CCL17 levels may help predict treatment responses in HES. In a large multi-center retrospective study, the geometric mean sTARC/CCL17 level was significantly higher in CS-responsive patients compared to non-responders (979 vs 242 pg/mL, p=0.01) [137]. In another study evaluating the efficacy of mepolizumab in patients with FIP1L1-PDGFRA-negative HES, a suboptimal hematological response to mepolizumab was observed in patients with elevated sTARC/CCL17 levels, whether or not they had L-HES [144].

The TARC/CCL17-CCR4 pathway as a therapeutic target in eosinophil-associated disorders

To date, two main approaches have been employed to target CCR4-positive cells and/or antagonize the actions of TARC/CCL17 and MDC/CCL22. The first one is represented by a MoAb specifically targeting the extracellular portion of CCR4, namely, mogamulizumab (KW0761). It is a defucosylated humanized IgG1 kappa MoAb that destroys CCR4-positive cells through ADCC and is approved for the treatment of certain T cell neoplasms [8, 145]. Of note, mogamulizumab administration can be associated with occurrence of severe skin reactions (e.g., SJS), probably as a consequence of CCR4+ Treg depletion [146]. Other MoAbs targeting different regions and presumably different conformations of CCR4 have also been designed with the potential to specifically interfere with TARC/CCL17 or MDC/CCL22 activities [68]. The second approach consists in small-molecule CCR4 antagonists [61]. Despite encouraging data from pre-clinical models, none of these small molecules have been registered to date [145].

Studies investigating the functional and clinical impact of targeting the TARC/CCL17-CCR4 axis have been conducted in murine models and in humans for several of the aforementioned eosinophil-associated diseases (Table 4).

Atopic dermatitis

In an ovalbumin-sensitized mouse model, the CCR4 antagonist compound 22 reduced AD-like lesions as well as CCR4+ T cell infiltrates in the skin [147]. In a canine model of AD however, another antagonist (AZ445) was unable to significantly reduce skin lesions compared to CS, although CCR4+ T cell numbers were locally reduced [148]. Similar antagonists are in development for humans [149]. Of note, the histamine H4 receptor antagonist (ZPL-3893787) which allegedly reduces TARC/CCL17 synthesis [150] was tested in subjects with AD in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial and was shown to reduce the SCORAD score and eczema area and severity index (EASI), but not pruritus [151].

Allergic asthma

To date, no therapy targeting TARC/CCL17 or CCR4 has been reported effective in human AA. In fact, among CCR4 antagonists shown to reduce allergic inflammation in mice, the only one tested in a phase I study in humans (GSK2239633) failed to induce sufficient CCR4 blockade at the highest dosing regimen [145]. Another phase I trial (NCT01514981) conducted with mogamulizumab was terminated prematurely due to drug-related adverse events. Finally, concerns have been raised regarding CCR4 blockade in asthma, as Tregs also express this receptor and are reported to colonize lung tissue and to be functional in the effector phase (“recall”) of allergic inflammation in murine models and in humans following segmental allergen challenge [152, 153].

T cell lymphoma

Mogamulizumab was evaluated in a phase III randomized controlled trial in comparison with vorinostat in relapsed/refractory MF and SS. Patients in the mogamulizumab arm had significantly longer progression-free survival (PFS) compared to vorinostat (median PFS of 7.7 months versus 3.1 months respectively, HR 0.53 with 95% CI 0.41–0.59) [154]. Mogamulizumab has also shown efficacy in ATLL when combined with intensive chemotherapy [155]. Indeed, its addition to background treatment resulted in improved PFS and overall survival, and it is now approved by Japanese authorities in newly diagnosed aggressive ATLL in combination with intensive chemotherapy [156].

L-HES

Ledoult and colleagues recently reported that circulating CD3-CD4+ cells bear a Th2 chemokine receptor phenotype ex vivo defined as CCR4+CCR6− in twenty patients with L-HES [157]. This phenotype was also expressed by 6 to 35% of CD3+CD4+ T cells from these patients and was not altered by CS therapy. These results have potential therapeutic implications as mogamulizumab could destroy the clonal IL-5-producing T cells that drive the disease.

Conclusion and perspectives

Both pre-clinical data and the clinical observations described herein firmly establish the intimate link between the TARC/CCL17-CCR4 axis, type 2 immunity, and eosinophilic inflammation. As such, TARC/CCL17 represents a useful biomarker for diagnosis and assessment of disease activity for several allegedly T cell-driven eosinophilic disorders and may also help predict more severe disease forms and/or treatment responses. Furthermore, overexpression/activation of this axis in these disorders makes it an appealing therapeutic target, as illustrated by the successful use of anti-CCR4 MoAb in certain T cell malignancies. Unfortunately, this approach has not yet produced results in the more common type 2 disorders such as AD and AA, and the potential impact on CCR4-expressing Tregs is a subject of concern. Future studies focusing on the precise role played by TARC/CCL17 in various eosinophilic conditions, mechanisms involved in its overexpression, CCR4 isoforms, and downstream signaling pathways will help determine whether the TARC/CCL17-CCR4 axis represents an interesting therapeutic target in non-malignant disorders.

AA allergic asthma, CLA cutaneous lymphocyte antigen, DC dendritic cell

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

Allergic asthma

- ABPA:

-

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

- ADCC:

-

Antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity

- AEC:

-

Absolute eosinophil count

- AEP:

-

Acute eosinophilic pneumonia

- AITL:

-

Angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma

- ALI:

-

Acute lung injury

- ANCA:

-

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ATLL:

-

Adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BALF:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- BM:

-

Bone marrow

- BP:

-

Bullous pemphigoid

- CC:

-

CC-chemokine

- CCR:

-

CC-chemokine receptor

- CEP:

-

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia

- CF:

-

Cystic fibrosis

- CLA:

-

Cutaneous lymphocyte antigen

- CRSwNP:

-

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps

- CRTH2:

-

Chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on Th2 cells

- CS:

-

Corticosteroid

- DC:

-

Dendritic cell

- DRESS:

-

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms

- EGPA:

-

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- FEV1:

-

Forced expired volume in one second

- FIP1L1:

-

Fip 1-like 1

- GPCR:

-

G protein-coupled receptor

- HC:

-

Healthy control

- HDM:

-

House dust mite

- HE:

-

Hypereosinophilia

- hEoP:

-

Human eosinophil progenitor

- HES:

-

Hypereosinophilic syndrome

- HHV:

-

Human herpes virus

- ICOG-Eo:

-

International Cooperative Working Group on Eosinophil Disorders

- IFN:

-

Interferon

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- ILC2:

-

Type 2 innate lymphoid cell

- LC:

-

Langerhans cell

- LN:

-

Lymph node

- MDC:

-

Macrophage-derived chemokine

- MF:

-

Mycosis fungoides

- MoAb:

-

Monoclonal antibody

- NFkB:

-

Nuclear factor-kappa B

- PBMC:

-

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PDGFRA:

-

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor A

- PFS:

-

Progression free survival

- PGD2:

-

Prostaglandin D2

- PTCL:

-

Peripheral T cell lymphoma

- PI3K:

-

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- SCORAD:

-

Scoring atopic dermatitis

- SJS:

-

Stevens-Johnson syndrome

- SS:

-

Sézary syndrome

- STAT:

-

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TARC:

-

Thymus and activation-regulated chemokine

- TGF:

-

Transforming growth factor

- TK:

-

Tyrosine kinase

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- Treg:

-

Regulatory T cell

- TSLP:

-

Thymic stromal lymphopoietin

- VCAM:

-

Vascular cell adhesion molecule

References

Genovese G, Di Zenzo G, Cozzani E, Berti E, Cugno M, Marzano AV (2019) New insights into the pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid: 2019 Update. Front Immunol 10:1506

Yamada Y, Rothenberg ME, Lee AW, Akei HS, Brandt EB, Williams DA, Cancelas JA (2006) The FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene cooperates with IL-5 to induce murine hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES)/chronic eosinophilic leukemia (CEL)–like disease. Blood 107:4071–4079

Molfino NA, Gossage D, Kolbeck R, Parker JM, Geba GP (2012) Molecular and clinical rationale for therapeutic targeting of interleukin-5 and its receptor. Clin Exp Allergy 42:712–737

Islam SA, Luster AD (2012) T cell homing to epithelial barriers in allergic disease. Nat Med 18:705–715

Imai T, Nagira M, Takagi S, Kakizaki M, Nishimura M, Wang J, Gray PW, Matsushima K, Yoshie O (1999) Selective recruitment of CCR4-bearing Th2 cells toward antigen-presenting cells by the CC chemokines thymus and activation-regulated chemokine and macrophage-derived chemokine. Int Immunol 11:81–88

Yoshie O, Matsushima K (2015) CCR4 and its ligands: from bench to bedside. Int Immunol 27:11–20

Landheer J, de Bruin-Weller M, Boonacker C, Hijnen D, Bruijnzeel-Koomen C, Röckmann H (2014) Utility of serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine as a biomarker for monitoring of atopic dermatitis severity. J Am Acad Dermatol 71:1160–1166

Ollila TA, Sahin I, Olszewski AJ (2019) Mogamulizumab: a new tool for management of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. OncoTargets Ther 12:1085–1094

Abbas A, Lichtman A, Pillai S (2018) Chapter 20: allergy. In: Cell. Mol. Immunol, 9th edn. Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 437–456

Hazenberg MD, Spits H (2014) Human innate lymphoid cells. Blood 124:700–709

Gurram RK, Zhu J (2019) Orchestration between ILC2s and Th2 cells in shaping type 2 immune responses. Cell Mol Immunol 16:225–235

Paul WE, Zhu J (2010) How are TH2-type immune responses initiated and amplified? Nat Rev Immunol 10:225–235

Walker JA, McKenzie ANJ (2018) TH2 cell development and function. Nat Rev Immunol 18:121–133

Islam SA, Chang DS, Colvin RA, Byrne MH, McCully ML, Moser B, Lira SA, Charo IF, Luster AD (2011) Mouse CCL8, a CCR8 agonist, promotes atopic dermatitis by recruiting IL-5+ TH2 cells. Nat Immunol 12:167–177

Komai-Koma M, Xu D, Li Y, McKenzie ANJ, McInnes IB, Liew FY (2007) IL-33 is a chemoattractant for human Th2 cells. Eur J Immunol 37:2779–2786

Galli SJ, Tsai M, Piliponsky AM (2008) The development of allergic inflammation. Nature 454:445–454

Mori Y, Iwasaki H, Kohno K et al (2009) Identification of the human eosinophil lineage-committed progenitor: revision of phenotypic definition of the human common myeloid progenitor. J Exp Med 206:183–193

Fulkerson PC (2017) Transcription factors in eosinophil development and as therapeutic targets. Front Med 4:115

Klion AD, Ackerman SJ, Bochner BS (2020) Contributions of eosinophils to human health and disease. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis 15:179–209

Nussbaum JC, Van Dyken SJ, von Moltke J et al (2013) Type 2 innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature 502:245–248

Molofsky AB, Nussbaum JC, Liang H-E, Van Dyken SJ, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A, Chawla A, Locksley RM (2013) Innate lymphoid type 2 cells sustain visceral adipose tissue eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages. J Exp Med 210:535–549

Kopf M, Brombacher F, Hodgkin PD et al (1996) IL-5-deficient mice have a developmental defect in CD5+ B-1 cells and lack eosinophilia but have normal antibody and cytotoxic T cell responses. Immunity 4:15–24

Marichal T, Mesnil C, Bureau F (2017) Homeostatic eosinophils: characteristics and functions. Front Med. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2017.00101

Ravensberg AJ, Ricciardolo FLM, van Schadewijk A, Rabe KF, Sterk PJ, Hiemstra PS, Mauad T (2005) Eotaxin-2 and eotaxin-3 expression is associated with persistent eosinophilic bronchial inflammation in patients with asthma after allergen challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol 115:779–785

Conroy DM, Williams TJ (2001) Eotaxin and the attraction of eosinophils to the asthmatic lung. Respir Res 2:150–156

Alblowi J, Tian C, Siqueira MF, Kayal RA, McKenzie E, Behl Y, Gerstenfeld L, Einhorn TA, Graves DT (2013) Chemokine expression is upregulated in chondrocytes in diabetic fracture healing. Bone 53:294–300

Cheng LE, Sullivan BM, Retana LE, Allen CDC, Liang H-E, Locksley RM (2015) IgE-activated basophils regulate eosinophil tissue entry by modulating endothelial function. J Exp Med 212:513–524

Singh D, Ravi A, Southworth T (2017) CRTH2 antagonists in asthma: current perspectives. Clin Pharmacol Adv Appl 9:165–173

Peinhaupt M, Sturm EM, Heinemann A (2017) Prostaglandins and their receptors in eosinophil function and as therapeutic Targets. Front Med 4:104

Fujishima H, Fukagawa K, Okada N, Takano Y, Tsubota K, Hirai H, Nagata K, Matsumoto K, Saito H (2005) Prostaglandin D2 induces chemotaxis in eosinophils via its receptor CRTH2 and eosinophils may cause severe ocular inflammation in patients with allergic conjunctivitis. Cornea 24:S66–S70

Wong CK, Hu S, Cheung PFY, Lam CWK (2010) Thymic stromal lymphopoietin induces chemotactic and prosurvival effects in eosinophils: implications in allergic inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 43:305–315

Liu LY, Jarjour NN, Busse WW, Kelly EAB (2003) Chemokine receptor expression on human eosinophils from peripheral blood and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after segmental antigen challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol 112:556–562

Yi S, Zhai J, Niu R et al (2018) Eosinophil recruitment is dynamically regulated by interplay among lung dendritic cell subsets after allergen challenge. Nat Commun 9:3879

Nagase H, Kudo K, Izumi S, Ohta K, Kobayashi N, Yamaguchi M, Matsushima K, Morita Y, Yamamoto K, Hirai K (2001) Chemokine receptor expression profile of eosinophils at inflamed tissue sites: decreased CCR3 and increased CXCR4 expression by lung eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol 108:563–569

Borchers MT, Ansay T, DeSalle R, Daugherty BL, Shen H, Metzger M, Lee NA, Lee JJ (2002) In vitro assessment of chemokine receptor-ligand interactions mediating mouse eosinophil migration. J Leukoc Biol 71:1033–1041

Bochner BS, Bickel CA, Taylor ML, MacGlashan DW, Gray PW, Raport CJ, Godiska R (1999) Macrophage-derived chemokine induces human eosinophil chemotaxis in a CC chemokine receptor 3– and CC chemokine receptor 4–independent manner. J Allergy Clin Immunol 103:527–532

Wilkerson EM, Johansson MW, Hebert AS, Westphall MS, Mathur SK, Jarjour NN, Schwantes EA, Mosher DF, Coon JJ (2016) The peripheral blood eosinophil proteome. J Proteome Res 15:1524–1533

Larose M-C, Archambault A-S, Provost V, Laviolette M, Flamand N (2017) Regulation of eosinophil and group 2 innate lymphoid cell trafficking in asthma. Front Med 4:136

Lee J, Rosenberg H (2013) Eosinophil secretory functions. In: Eosinophils Health Dis. Elsevier, pp 229–275

Ramirez GA, Yacoub M-R, Ripa M, Mannina D, Cariddi A, Saporiti N, Ciceri F, Castagna A, Colombo G, Dagna L (2018) Eosinophils from physiology to disease: a comprehensive review. Biomed Res Int 2018:1–28

Curtis C, Ogbogu P (2016) Hypereosinophilic syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 50:240–251

Valent P, Klion AD, Horny H-P et al (2012) Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 130:607–612.e9

Chusid M, Dale D, West B, Wolff S (1975) The hypereosinophilic syndrome: analysis of fourteen cases with review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 54(1):1–27

Roufosse F, Weller PF (2010) Practical approach to the patient with hypereosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol 126:39–44

Cools J, DeAngelo DJ, Gotlib J et al (2003) A tyrosine kinase created by fusion of the PDGFRA and FIP1L1 genes as a therapeutic target of imatinib in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. N Engl J Med 348:1201–1214

Cogan E, Schandené L, Crusiaux A, Cochaux P, Velu T, Goldman M (1994) Brief report: clonal proliferation of type 2 helper T cells in a man with the hypereosinophilic syndrome. N Engl J Med 330:535–538

Klion AD (2015) How I treat hypereosinophilic syndromes. Blood 126:1069–1077

Imai T, Yoshida T, Baba M, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Yoshie O (1996) Molecular cloning of a novel T cell-directed CC chemokine expressed in thymus by signal sequence trap using Epstein-Barr virus vector. J Biol Chem 271:21514–21521

Imai T, Baba M, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Takagi S, Yoshie O (1997) The T cell-directed CC chemokine TARC is a highly specific biological ligand for CC chemokine receptor 4. J Biol Chem 272:15036–15042

Nomiyama H, Imai T, Kusuda J, Miura R, Callen DF, Yoshie O (1997) Assignment of the human CC chemokine gene TARC (SCYA17) to chromosome 16q13. Genomics 40:211–213

Alferink J, Lieberam I, Reindl W et al (2003) Compartmentalized production of CCL17 in vivo. J Exp Med 197:585–599

Achuthan A, Cook AD, Lee M-C et al (2016) Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces CCL17 production via IRF4 to mediate inflammation. J Clin Invest 126:3453–3466

Hsu AT, Lupancu TJ, Lee M-C, Fleetwood AJ, Cook AD, Hamilton JA, Achuthan A (2018) Epigenetic and transcriptional regulation of IL4-induced CCL17 production in human monocytes and murine macrophages. J Biol Chem 293:11415–11423

Medoff BD, Seung E, Hong S, Thomas SY, Sandall BP, Duffield JS, Kuperman DA, Erle DJ, Luster AD (2009) CD11b+ myeloid cells are the key mediators of Th2 cell homing into the airway in allergic inflammation. J Immunol 182:623–635

Wirnsberger G, Hebenstreit D, Posselt G, Horejs-Hoeck J, Duschl A (2006) IL-4 induces expression of TARC/CCL17via two STAT6 binding sites. Eur J Immunol 36:1882–1891

Kakinuma T, Nakamura K, Wakugawa M, Yano S, Saeki H, Torii H, Komine M, Asahina A, Tamaki K (2002) IL-4, but not IL-13, modulates TARC (thymus and activation-regulated chemokine)/CCL17 and IP-10 (interferon-induced protein of 10kDa)/CXCL10 release by TNF-α and IFN-γ in HaCaT cell line. Cytokine 20:1–6

Sekiya T, Miyamasu M, Imanishi M et al (2000) Inducible expression of a Th2-type CC chemokine thymus- and activation-regulated chemokine by human bronchial epithelial cells. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950 165:2205–2213

Berin MC, Eckmann L, Broide DH, Kagnoff MF (2001) Regulated production of the T helper 2–Type T-cell chemoattractant TARC by human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro and in human lung xenografts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 24:382–389

Nakayama T, Hieshima K, Nagakubo D, Sato E, Nakayama M, Kawa K, Yoshie O (2004) Selective induction of Th2-attracting chemokines CCL17 and CCL22 in human B cells by latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol 78:1665–1674

Fujii-Maeda S, Kajiwara K, Ikizawa K, Shinazawa M, Yu B, Koga T, Furue M, Yanagihara Y (2004) Reciprocal regulation of thymus and activation-regulated chemokine/macrophage-derived chemokine production by interleukin (IL)-4/IL-13 and interferon-γ in HaCaT keratinocytes is mediated by alternations in E-cadherin distribution. J Invest Dermatol 122:20–28

Solari R, Pease JE (2015) Targeting chemokine receptors in disease – a case study of CCR4. Eur J Pharmacol 763:169–177

Imai T, Chantry D, Raport CJ, Wood CL, Nishimura M, Godiska R, Yoshie O, Gray PW (1998) Macrophage-derived chemokine is a functional ligand for the cc chemokine receptor 4. J Biol Chem 273:1764–1768

Vulcano M, Albanesi C, Stoppacciaro A et al (2001) Dendritic cells as a major source of macrophage-derived chemokine/CCL22 in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Immunol 31:812–822

Yamashita U, Kuroda E (2002) Regulation of macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC, CCL22) production. Crit Rev Immunol 22:105–114

Hashimoto S, Nakamura K, Oyama N, Kaneko F, Tsunemi Y, Saeki H, Tamaki K (2006) Macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC)/CCL22 produced by monocyte derived dendritic cells reflects the disease activity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci 44:93–99

D’Ambrosio D, Albanesi C, Lang R, Girolomoni G, Sinigaglia F, Laudanna C (2002) Quantitative differences in chemokine receptor engagement generate diversity in integrin-dependent lymphocyte adhesion. J Immunol 169:2303–2312

Mariani M, Lang R, Binda E, Panina-Bordignon P, D’Ambrosio D (2004) Dominance of CCL22 over CCL17 in induction of chemokine receptor CCR4 desensitization and internalization on human Th2 cells. Eur J Immunol 34:231–240

Viney JM, Andrew DP, Phillips RM, Meiser A, Patel P, Lennartz-Walker M, Cousins DJ, Barton NP, Hall DA, Pease JE (2014) Distinct conformations of the chemokine receptor CCR4 with implications for its targeting in allergy. J Immunol 192:3419–3427

Lin R, Choi Y, Zidar DA, Walker JKL (2018) β-arrestin-2–dependent signaling promotes CCR4–mediated chemotaxis of murine T-helper type 2 cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 58:745–755

Weston CA, Rana BMJ, Cousins DJ (2019) Differential expression of functional chemokine receptors on human blood and lung group 2 innate lymphoid cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 143:410–413.e9

Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD (2018) Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primer 4:1

Oldhoff JM, Darsow U, Werfel T et al (2005) Anti-IL-5 recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody (mepolizumab) for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Allergy 60:693–696

Kang EG, Narayana PK, Pouliquen IJ, Lopez MC, Ferreira-Cornwell MC, Getsy JA (2020) Efficacy and safety of mepolizumab administered subcutaneously for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. Allergy 75:950–953

Saeki H, Tamaki K (2006) Thymus and activation regulated chemokine (TARC)/CCL17 and skin diseases. J Dermatol Sci 43:75–84

Kakinuma T, Nakamura K, Wakugawa M et al (2001) Thymus and activation-regulated chemokine in atopic dermatitis: serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine level is closely related with disease activity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 107:535–541

Rubin LA, Nelson DL (1990) The soluble interleukin-2 receptor: biology, function, and clinical application. Ann Intern Med 113:619–627

Vestergaard C, Bang K, Gesser B, Yoneyama H, Matsushima K, Larsen CG (2000) A Th2 chemokine, TARC, produced by keratinocytes may recruit CLA+CCR4+ lymphocytes into lesional atopic dermatitis skin. J Invest Dermatol 115:640–646

Wakugawa M, Nakamura K, Kakinuma T, Onai N, Matsushima K, Tamaki K (2001) CC chemokine receptor 4 expression on peripheral blood CD4+ T cells reflects disease activity of atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 117:188–196

Jang M, Kim H, Kim Y, Choi J, Jeon J, Hwang Y, Kang JS, Lee WJ (2016) The crucial role of IL-22 and its receptor in thymus and activation regulated chemokine production and T-cell migration by house dust mite extract. Exp Dermatol 25:598–603

Zhang Y-Y, Wang A-X, Xu L, Shen N, Zhu J, Tu C-X (2016) Characteristics of peripheral blood CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells and related cytokines in severe atopic dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol 26:240–246

Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA (2013) DRESS syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 68:693.e1–693.e14

Ogawa K, Morito H, Hasegawa A et al (2013) Identification of thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC/CCL17) as a potential marker for early indication of disease and prediction of disease activity in drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS)/drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). J Dermatol Sci 69:38–43

Ogawa K, Morito H, Hasegawa A et al (2014) Elevated serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC/CCL17) relates to reactivation of human herpesvirus 6 in drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS)/drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS). Br J Dermatol 171:425–427

Watanabe H (2018) Recent advances in drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. J Immunol Res 2018:1–10

Lin L, Hwang B-J, Culton DA et al (2018) Eosinophils mediate tissue injury in the autoimmune skin disease bullous pemphigoid. J Invest Dermatol 138:1032–1043

Kakinuma T, Wakugawa M, Nakamura K, Hino H, Matsushima K, Tamaki K (2003) High level of thymus and activation-regulated chemokine in blister fluid and sera of patients with bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol 148:203–210

Miyashiro D, Sanches JA (2020) Erythroderma: a prospective study of 309 patients followed for 12 years in a tertiary center. Sci Rep 10:9774

Nakano-Tahara M, Terao M, Nishioka M, Kitaba S, Murota H, Katayama I (2015) T Helper 2 polarization in senile erythroderma with elevated levels of TARC and IgE. Dermatology 230:62–69

Ohga Y, Bayaraa B, Imafuku S (2018) Chronic idiopathic erythroderma of elderly men is an independent entity that has a distinct TARC/IgE profile from adult atopic dermatitis. Int J Dermatol 57:670–674

Murayama T, Nakamura K, Tsuchida T (2015) Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis with extensive distribution: correlation of serum TARC levels and peripheral blood eosinophil numbers. Int J Dermatol 54:1071–1074

Zhang L, Qi R, Yang Y, Gao X, Chen H, Xiao T (2019) Serum miR-125a-5p and CCL17 upregulated in chronic spontaneous urticaria and correlated with treatment response. Acta Derm Venereol 99:571–578

Tapia B, Morel E, Martín-Díaz M-A, Díaz R, Alves-Ferreira J, Rubio P, Padial A, Bellón T (2007) Up-regulation of CCL17, CCL22 and CCR4 in drug-induced maculopapular exanthema. Clin Exp Allergy J Br Soc Allergy Clin Immunol 37:704–713

Quaglino P, Caproni M, Antiga E et al (2007) Serum levels of the Th1 promoter IL-12 and the Th2 chemokine TARC are elevated in erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and correlate with soluble Fas ligand expression. An immunoenzymatic study from the Italian Group of Immunopathology. Dermatology 214:296–304

Teraki Y, Taguchi R (2014) Serum TARC levels correlate with disease activity in patients with non-episodic angioedema with eosinophilia. J Dermatol 41:858–860

Khoury P, Herold J, Alpaugh A et al (2015) Episodic angioedema with eosinophilia (Gleich syndrome) is a multilineage cell cycling disorder. Haematologica 100:300–307

Chen R, Smith SG, Salter B, El-Gammal A, Oliveria JP, Obminski C, Watson R, O’Byrne PM, Gauvreau GM, Sehmi R (2017) Allergen-induced increases in sputum levels of group 2 innate lymphoid cells in subjects with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 196:700–712

Emma R, Morjaria JB, Fuochi V, Polosa R, Caruso M (2018) Mepolizumab in the management of severe eosinophilic asthma in adults: current evidence and practical experience. Ther Adv Respir Dis 12:1–12

Vijayanand P, Durkin K, Hartmann G et al (2010) Chemokine receptor 4 plays a key role in T cell recruitment into the airways of asthmatic patients. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950 184:4568–4574

Bochner BS, Hudson SA, Xiao HQ, Liu MC (2003) Release of both CCR4-active and CXCR3-active chemokines during human allergic pulmonary late-phase reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol 112:930–934

Pilette C, Francis JN, Till SJ, Durham SR (2004) CCR4 ligands are up-regulated in the airways of atopic asthmatics after segmental allergen challenge. Eur Respir J 23:876–884

Heijink IH, Marcel Kies P, van Oosterhout AJM, Postma DS, Kauffman HF, Vellenga E (2007) Der p, IL-4, and TGF-β cooperatively induce EGFR-dependent TARC expression in airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 36:351–359

Perros F, Hoogsteden HC, Coyle AJ, Lambrecht BN, Hammad H (2009) Blockade of CCR4 in a humanized model of asthma reveals a critical role for DC-derived CCL17 and CCL22 in attracting Th2 cells and inducing airway inflammation. Allergy 64:995–1002

Staples KJ, Hinks TSC, Ward JA, Gunn V, Smith C, Djukanović R (2012) Phenotypic characterization of lung macrophages in asthmatic patients: overexpression of CCL17. J Allergy Clin Immunol 130:1404–1412.e7

Hirata H, Arima M, Cheng G, Honda K, Fukushima F, Yoshida N, Eda F, Fukuda T (2002) Production of TARC and MDC by naive T cells in asthmatic patients. J Clin Immunol 23:12

Jacobsen EA, Ochkur SI, Pero RS, Taranova AG, Protheroe CA, Colbert DC, Lee NA, Lee JJ (2008) Allergic pulmonary inflammation in mice is dependent on eosinophil-induced recruitment of effector T cells. J Exp Med 205:699–710

Liu LY, Bates ME, Jarjour NN, Busse WW, Bertics PJ, Kelly EAB (2007) Generation of Th1 and Th2 chemokines by human eosinophils: evidence for a critical role of TNF-α. J Immunol 179:4840–4848

Chvatchko Y, Hoogewerf AJ, Meyer A, Alouani S, Juillard P, Buser R, Conquet F, Proudfoot AEI, Wells TNC, Power CA (2000) A key role for CC chemokine receptor 4 in lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxic shock. J Exp Med 191:1755–1763

Kawasaki S, Takizawa H, Yoneyama H et al (2001) Intervention of thymus and activation-regulated chemokine attenuates the development of allergic airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Immunol 166:2055–2062

Conroy DM, Jopling LA, Lloyd CM, Hodge MR, Andrew DP, Williams TJ, Pease JE, Sabroe I (2003) CCR4 blockade does not inhibit allergic airways inflammation. J Leukoc Biol 74:558–563

Honjo A, Ogawa H, Azuma M, Tezuka T, Sone S, Biragyn A, Nishioka Y (2013) Targeted reduction of CCR4+ cells is sufficient to suppress allergic airway inflammation. Respir Investig 51:241–249

Tsybikov NN, Fefelova EV (2016) Biomarker assessment in chronic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis: endothelin-1, TARC/CCL17, neopterin, and. Allergy Asthma Proc 37:35–42

Hartl D, Latzin P, Zissel G, Krane M, Krauss-Etschmann S, Griese M (2006) Chemokines indicate allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173:1370–1376

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA et al (2013) 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 65:1–11

Gioffredi A, Maritati F, Oliva E, Buzio C (2014) Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: an overview. Front Immunol 5:549

Dallos T, Heiland GR, Strehl J et al (2010) CCL17/thymus and activation-related chemokine in Churg-Strauss syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 62:3496–3503

Dejaco C, Oppl B, Monach P et al (2015) Serum biomarkers in patients with relapsing eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss). PLoS One 10:e0121737

Khoury P, Zagallo P, Talar-Williams C, Santos CS, Dinerman E, Holland NC, Klion AD (2012) Serum biomarkers are similar in Churg-Strauss syndrome and hypereosinophilic syndrome. Allergy 67:1149–1156

Suzuki Y, Suda T (2019) Eosinophilic pneumonia: a review of the previous literature, causes, diagnosis, and management. Allergol Int 68:413–419

Miyazaki E, Nureki S, Fukami T, Shigenaga T, Ando M, Ito K, Ando H, Sugisaki K, Kumamoto T, Tsuda T (2002) Elevated levels of thymus- and activation-regulated chemokine in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with eosinophilic pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165:1125–1131

Miyazaki E, Nureki S, Ono E, Ando M, Matsuno O, Fukami T, Ueno T, Kumamoto T (2007) Circulating thymus- and activation-regulated chemokine/CCL17 is a useful biomarker for discriminating acute eosinophilic pneumonia from other causes of acute lung injury. Chest 131:1726–1734

Nureki S, Miyazaki E, Ando M, Kumamoto T, Tsuda T (2005) CC chemokine receptor 4 ligand production by bronchoalveolar lavage fluid cells in cigarette-smoke-associated acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Clin Immunol 116:83–93

Katoh S, Fukushima K, Matsumoto N, Matsumoto K, Abe K, Onai N, Matsushima K, Matsukura S (2003) Accumulation of CCR4-expressing CD4+ T cells and high concentration of its ligands (TARC and MDC) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with eosinophilic pneumonia. Allergy 58:518–523

Nakagome K, Shoda H, Shirai T, Nishihara F, Soma T, Uchida Y, Sakamoto Y, Nagata M (2017) Eosinophil transendothelial migration induced by the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of acute eosinophilic pneumonia: eosinophil accumulation in AEP. Respirology 22:913–921

Hristov AC, Tejasvi T, Wilcox RA (2019) Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 94:1027–1041

Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, Moskowitz A, Querfeld C (2014) Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome). J Am Acad Dermatol 70:205.e1–205.e16

Tamaki K, Kakinuma T, Saeki H et al (2006) Serum levels of CCL17/TARC in various skin diseases. J Dermatol 33:300–302

Kakinuma T, Sugaya M, Nakamura K, Kaneko F, Wakugawa M, Matsushima K, Tamaki K (2003) Thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC/CCL17) in mycosis fungoides: serum TARC levels reflect the disease activity of mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol 48:23–30

Sugaya M, Morimura S, Suga H, Kawaguchi M, Miyagaki T, Ohmatsu H, Fujita H, Sato S (2015) CCR4 is expressed on infiltrating cells in lesional skin of early mycosis fungoides and atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol 42:613–615

Ishida T, Inagaki H, Utsunomiya A, Takatsuka Y, Komatsu H, Iida S, Takeuchi G, Eimoto T, Nakamura S, Ueda R (2004) CXC chemokine receptoR 3 and CC chemokine receptor 4 expression in T- cell and NK-cell lymphomas with special reference to clinicopathological significance for peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified. Clin Cancer Res 10:5494–5500

Thielen C, Radermacher V, Trimeche M, Roufosse F, Goldman M, Boniver J, de Leval L (2008) TARC and IL-5 expression correlates with tissue eosinophilia in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Leuk Res 32:1431–1438

Yoshie O, Fujisawa R, Nakayama T et al (2002) Frequent expression of CCR4 in adult T-cell leukemia and human T-cell leukemia virus type 1–transformed T cells. Blood 99:1505–1511

Roufosse F, Cogan E, Goldman M (2007) Lymphocytic variant hypereosinophilic syndromes. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am 27:389–413

Lefèvre G, Copin M-C, Staumont-Sallé D et al (2014) The lymphoid variant of hypereosinophilic syndrome: study of 21 patients with CD3-CD4+ aberrant T-cell phenotype. Medicine (Baltimore) 93:255–266

Carpentier C, Verbanck S, Schandené L, Heimann P, Trépant A-L, Cogan E, Roufosse F (2020) Eosinophilia associated with CD3−CD4+ T cells: characterization and outcome of a single-center cohort of 26 patients. Front Immunol 11:1765

de Lavareille A, Roufosse F, Schandené L, Stordeur P, Cogan E, Goldman M (2001) Clonal Th2 cells associated with chronic hypereosinophilia: TARC-induced CCR4 down-regulation in vivo. Eur J Immunol 31:1037–1046

de Lavareille A, Roufosse F, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Roumier A-S, Schandené L, Cogan E, Simon H-U, Goldman M (2002) High serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine levels in the lymphocytic variant of the hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 110:476–479

Ogbogu PU, Bochner BS, Butterfield JH et al (2009) Hypereosinophilic syndrome: a multicenter, retrospective analysis of clinical characteristics and response to therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 124:1319–1325.e3

Suzuki M, Yamaguchi Y, Nakamura K, Kanaoka M, Matsukura S, Takahashi K, Takahashi Y, Kambara T, Aihara M (2020) Serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC/CCL17) may be useful to predict the disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16851

Machida H, Inoue S, Shibata Y et al (2021) Thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC/CCL17) predicts decline of pulmonary function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Allergol Int 70:81–88

Latzin P, Hartl D, Regamey N, Frey U, Schoeni MH, Casaulta C (2008) Comparison of serum markers for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J 31:36–42

Shono Y, Suga H, Kamijo H, Fujii H, Oka T, Miyagaki T, Shishido-Takahashi N, Sugaya M, Sato S (2019) Expression of CCR3 and CCR4 suggests a poor prognosis in mycosis Fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol 99:809–812

Ishida T, Utsunomiya A, Iida S et al (2003) Clinical significance of CCR4 expression in adult T-cell leukemia/ lymphoma: its close association with skin involvement and unfavorable outcome. Cancer Res 9:3625–3634

Carpentier C, Schandené L, Dewispelaere L, Heimann P, Cogan E, Roufosse F (2021) CD3−CD4+ Lymphocytic variant hypereosinophilic syndrome: diagnostic tools revisited. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2021.01.030

Roufosse F, de Lavareille A, Schandené L, Cogan E, Georgelas A, Wagner L, Xi L, Raffeld M, Goldman M, Gleich GJ (2010) Mepolizumab as a corticosteroid-sparing agent in lymphocytic variant hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 126:828–835.e3

Pease JE, Horuk R (2014) Recent progress in the development of antagonists to the chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR4. Expert Opin Drug Discovery 9:467–483

Ishida T, Ito A, Sato F, Kusumoto S, Iida S, Inagaki H, Morita A, Akinaga S, Ueda R (2013) Stevens-Johnson syndrome associated with mogamulizumab treatment of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Cancer Sci 104:647–650