Abstract

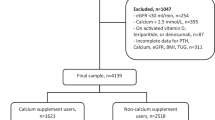

We aimed to characterize incident users of alendronate from Denmark and Spain, and investigate their eligibility for participation in the pivotal Fracture Intervention Trial (FIT). This is an international cross-sectional study, where the data were obtained from the SIDIAP database (Sistema d’Informació per al Desenvolupament de l’Investigació en Atenció Primària) from Catalonia (Spain) and the Danish Health Registries (DHR). This study included patients who were incident users of alendronate, ≥40 years old with no history of Paget’s disease. Our measurements were the proportion of incident users of alendronate who were not eligible to participate in FIT. 14,316 and 21,221 subjects initiated alendronate in 2006–2007 (SIDIAP) and 2005–2006 (DHR), respectively. SIDIAP and DHR alendronate user cohorts had 2347 (16.4 %) and 5275 (24.9 %) subjects aged >80 years old, reported 9 (0.1 %) and 91 (0.4 %) diagnoses of myocardial infarction, 423 (3 %) and 368 (1.7 %) of erosive gastro-intestinal disease, 200 (1.4 %) and 1109 (5.2 %) of dyspepsia, and 349 (2.4 %) and 149 (0.7 %) of metabolic bone disease, all of which were exclusion criteria in FIT. Men [3818 (26.7 %) in SIDIAP and 3885 (18.3 %) in DHR] and glucocorticoid users [1229 (8.6 %) in SIDIAP and 4716 (22.2 %) in DHR] were also excluded from the FIT trial. Overall, 3447 (35.4 %) SIDIAP and 6228 (44.5 %) (when not considering men and glucocorticoid users) DHR of incident alendronate users would have been excluded from FIT. One in two real-life users of alendronate exhibited one or more clinical characteristics that would have led to them being excluded from the FIT trial.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rothwell PM (2005) External validity of randomised controlled trials: “to whom do the results of this trial apply?”. Lancet 365:82–93

Taylor RS, Bethell HJN, Brodie DA (2007) Clinical trials versus the real world: the example of cardiac rehabilitation. Br J Cardiol 14:175–178

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG (2001) The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-grouprandomised trials. Lancet 357:1191–1194

Jolliffe JA, Rees K, Taylor RS, Thompson D, Oldridge N, Ebrahim S (2001) Exercise-based rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD001800

Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC, Bauer DC, Genant HK, Haskell WL, Marcus R, Ott SM, Torner JC, Quandt SA, Reiss TF, Ensrud KE (1996) Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet 348:1535–1541

Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, Applegate WB, Barrett-Connor E, Musliner TA, Palermo L, Prineas R, Rubin SM, Scott JC, Vogt T, Wallace R, Yates AJ, LaCroix AZ (1998) Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA 280:2077–2082

Cadarette SM, Katz JN, Brookhart MA, Stürmer T, Stedman MR, Solomon DH (2008) Relative effectiveness of osteoporosis drugs for preventing nonvertebral fracture. Ann Intern Med 148:637–646

Feldstein AC, Weycker D, Nichols GA, Oster G, Rosales G, Boardman DL, Perrin N (2009) Effectiveness of bisphosphonate therapy in a community setting. Bone 44:153–159

Erviti J, Alonso A, Gorricho J, López A (2013) Oral bisphosphonates may not decrease hip fracture risk in elderly Spanish women: a nested case–control study. BMJ Open 3:e002084

Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Eastell R (2010) Cumulative alendronate dose and the long-term absolute risk of subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures: a register-based national cohort analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:5258–5265

Ramos R, Balló E, Marrugat J, Elosúa R, Sala J, Grau M, Vila J, Bolíbar B, García-Gil M, Martí R, Fina F, Hermosilla E, Rosell M, Muñoz MA, Prieto-Alhambra D, Quesada M (2012) Validity for use in research on vascular diseases of the SIDIAP [Information System for the Development of Research in Primary Care]: the EMMA study. Rev EspCardiol [Engl Ed] 65:29–37

Garcia-Gil M, Hermosilla E, Prieto-Alhambra D, Fina F, Rossell M, Ramos R, Rodriguez J, Williams T, Van Staa T, Bolíbar B (2011) Construction and validation of a scoring system for selection of high quality data in a spanish population primary care database [SIDIAP]. Inform Prim Care 19:135–145

Kildemoes HW, Sørensen HT, Hallas J (2011) The Danish national prescription registry. Scand J Public Health 39:38–41

Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M (2011) The Danish national patient register. Scand J Public Health 39:30–33

Pedersen CB (2011) The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health 39:22–25

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, Saunders LD, Beck CA, Feasby TE, Ghali WA (2005) Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 43:1130–1139

Orwoll E, Ettinger M, Weiss S, Miller P, Kendler D, Graham J, Adami S, Weber K, Lorenc R, Pietschmann P, Vandormael K, Lombardi A (2000) Alendronate for the treatment of osteoporosis in men. N Engl J Med 343:604–610

Saag KG, Emkey R, Schnitzer TJ, Brown JP, Hawkins F, Goemaere S, Thamsborg G, Liberman UA, Delmas PD, Malice MP, Czachur M, Daifotis AG (1998) Alendronate for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis Intervention Study Group. N Engl J Med 339:292–299

Liberman UA, Weiss SR, Bröll J, Minne HW, Quan H, Bell NH, Rodriguez-Portales J, Downs RW Jr, Dequeker J, Favus M (1995) Effect of oral alendronate on bone mineral density and the incidence of fractures in postmenopausal osteoporosis. The Alendronate Phase III Osteoporosis Treatment Study Group. N Engl J Med 333:1437–1443

Zulman DM, Sussman JB, Chen X, Cigolle CT, Blaum CS, Hayward RA (2011) Examining the evidence: a systematic review of the inclusion and analysis of older adults in randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med 26:783–790

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E (2008) FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int 19:385–397

Fortin M, Dionne J, Pinho G, Gignac J, Almirall J, Lapointe L (2006) Randomized controlled trials: do they have external validity for patients with multiple comorbidities? Ann Fam Med 4:104–108

Coca SG, Krumholz HM, Garg AX, Parikh CR (2006) Underrepresentation of renal disease in randomized controlled trials of cardiovascular disease. JAMA 296:1377–1384

Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Lee DS, Kopp A, Austin PC, Laupacis A, Redelmeier DA (2004) Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study. N Engl J Med 351:543–551

Grapow MT, von Wattenwyl R, Guller U, Beyersdorf F, Zerkowski HR (2006) Randomized controlled trials do not reflect reality: real-world analyses are critical for treatment guidelines! J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 132:5–7

Black DM et al (1993) Design of the Fracture Intervention Trial. Osteoporos Int 3(Suppl 3):S29–S39

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the health professionals (general practitioners and nurses) responsible for the collection of these data, as well as to the patients involved. DPA receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research Clinician Scientist award scheme. ADP affirms that he has listed everyone who contributed significantly to the work. All authors had access to all the study data, take responsibility for the accuracy of the analysis, and had authority over manuscript preparation and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author’s Contributors Statement

DPA, BA, and CR: Data extraction, statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation. DPA: Study design, data analysis, and interpretation and manuscript preparation. CR: data interpretation and manuscript preparation. MKJ, CC, ADP: study design and manuscript preparation. AP, PS, and TVS: manuscript preparation. All authors revised the paper critically for intellectual content and approved the final version. All authors agree to be accountable for the work and to ensure that any questions relating to the accuracy and integrity of the paper are investigated and properly resolved.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

P. S, C. R, and A. P declare that they have no conflict of interest; D. P. A: Scientific Coordinator of the SIDIAP Database. Unrestricted research grants from Amgen and Bioiberica; A.D.P: speaker or advisor for Lilly, Amgen, UCB, Active Life Sci; C.C: received consultancy, lecture fees and honoraria from Alliance for Better Bone Health, AMGEN, Eli Lilly, GSK, Medtronic, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Servier and Takeda. (outside the submitted work); K.J: personal fees from consultancy, lecture fees and/or honoraria from AMGEN, GSK, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Servier, Medtronic and Roche outside the submitted work; B.A: research grants from or served as an investigator in studies for Novartis, Takeda, NPS Pharmaceuticals and Amgen; T.V.S: advisory boards for GSK and Boehringer and advice to Laser Rx on epidemiological and pragmatic trial methods outside the submitted work.

Human and Animal Rights

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Informed Consent

Patient consent was not required (anonymised retrospective data).

Additional information

Bo Abrahamsen and Daniel Prieto-Alhambra are Joint senior authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reyes, C., Pottegård, A., Schwarz, P. et al. Real-Life and RCT Participants: Alendronate Users Versus FITs’ Trial Eligibility Criterion. Calcif Tissue Int 99, 243–249 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-016-0141-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-016-0141-7