Abstract

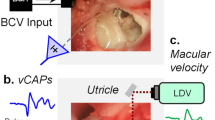

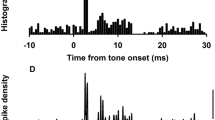

Previous studies have shown that the vestibular short-latency-evoked potential (VsEP) in response to the brief head acceleration stimulus is a compound action potential of neurons innervating the otolith organs. However, due to the lack of direct evidence, it is currently unclear whether the VsEP is primarily generated by the activity of utricular or saccular afferent neurons, or some mixture of the two. Here, we investigated the origin of the VsEP evoked by brief bone-conducted vibration pulses in guinea pigs, using selective destruction of the cochlea, semicircular canals (SCCs), saccule, or utricle, along with neural blockade with tetrodotoxin (TTX) application, and mechanical displacements of the surgically exposed utricular macula. To access each end organ, either a dorsal or a ventral surgical approach was used. TTX application abolished the VsEP, supporting the neurogenic origin of the response. Selective cochlear, SCCs, or saccular destruction had no significant effect on VsEP amplitude, whereas utricular destruction abolished the VsEP completely. Displacement of the utricular membrane changed the VsEP amplitude in a non-monotonic fashion. These results suggest that the VsEP evoked by BCV in guinea pigs represents almost entirely a utricular response. Furthermore, it suggests that displacements of the utricular macula may alter its response to bone-conduction stimuli.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- VsEP:

-

Vestibular short-latency-evoked response

- RW:

-

Round window

- SCC:

-

Semicircular canal

- CAP:

-

Compound action potential

- MD:

-

Ménière’s disease

- BCV:

-

Bone-conducted vibration

References

Bohmer A (1995) Short latency vestibular evoked responses to linear acceleration stimuli in small mammals: masking effects and experimental applications. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 520(Pt 1):120–123

Bohmer A, Hoffman LF, Honrubia V (1995) Characterization of vestibular potentials evoked by linear acceleration pulses in the chinchilla. Am J Otol 16:498–504

Brantberg K, Lofqvist L, Westin M, Tribukait A (2008) Skull tap induced vestibular evoked myogenic potentials: an ipsilateral vibration response and a bilateral head acceleration response? Clin Neurophysiol 119:2363–2369

Bremer HG, de Groot JC, Versnel H, Klis SF (2012) Combined administration of kanamycin and furosemide does not result in loss of vestibular function in Guinea pigs. Audiol Neurootol 17:25–38

Chiappa K (1997) Evoked potentials in clinical medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Colebatch JG, Halmagyi GM (1992) Vestibular evoked potentials in human neck muscles before and after unilateral vestibular deafferentation. Neurology 42:1635–1636

Colebatch JG, Halmagyi GM, Skuse NF (1994) Myogenic potentials generated by a click-evoked vestibulocollic reflex. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 57:190–197

Curthoys IS (2012) The interpretation of clinical tests of peripheral vestibular function. Laryngoscope 122:1342–1352

Curthoys IS, Vulovic V (2011) Vestibular primary afferent responses to sound and vibration in the guinea pig. Exp Brain Res 210:347–352. doi:10.1007/s00221-010-2499-5

Curthoys IS, Kim J, McPhedran SK, Camp AJ (2006) Bone conducted vibration selectively activates irregular primary otolithic vestibular neurons in the guinea pig. Exp Brain Res 175:256–267

Curthoys IS, Uzun-Coruhlu H, Wong CC, Jones AS, Bradshaw AP (2009) The configuration and attachment of the utricular and saccular maculae to the temporal bone. New evidence from microtomography-CT studies of the membranous labyrinth. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1164:13–18

Curthoys IS, Vulovic V, Sokolic L, Pogson J, Burgess AM (2012) Irregular primary otolith afferents from the guinea pig utricular and saccular maculae respond to both bone conducted vibration and to air conducted sound. Brain Res Bull 89:16–21

Elidan J, Langhofer L, Honrubia V (1987a) The neural generators of the vestibular evoked response. Brain Res 423:385–390

Elidan J, Langhofer L, Honrubia V (1987b) Recording of short-latency vestibular evoked potentials induced by acceleration impulses in experimental animals: current status of the method and its applications. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 68:58–69

Freeman S, Plotnik M, Elidan J, Rosen LJ, Sohmer H (1999) Effect of white noise “masking” on vestibular evoked potentials recorded using different stimulus modalities. Acta Otolaryngol 119:311–315

Goldberg JM (2000) Afferent diversity and the organization of central vestibular pathways. Exp Brain Res 130:277–297

Halmagyi GM, Yavor RA, Colebatch JG (1995) Tapping the head activates the vestibular system: a new use for the clinical reflex hammer. Neurology 45:1927–1929

Hara M, Kimura RS (1993) Morphology of the membrana limitans. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 102:625–630

Jones TA (1992) Vestibular short latency responses to pulsed linear acceleration in unanesthetized animals. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 82:377–386

Jones TA, Jones SM (1999) Short latency compound action potentials from mammalian gravity receptor organs. Hear Res 136:75–85

Jones TA, Jones SM (2007) Vestibular evoked potentials. In: Burkard RF, Eggermont JJ, Don M (eds) Auditory evoked potentials: basic principles and clinical application. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, pp 622–650

Jones TA, Pedersen TL (1989) Short latency vestibular responses to pulsed linear acceleration. Am J Otolaryngol 10:327–335

Jones TA, Jones SM, Colbert S (1998) The adequate stimulus for avian short latency vestibular responses to linear translation. J Vestib Res 8:253–272

Jones SM, Erway LC, Bergstrom RA, Schimenti JC, Jones TA (1999) Vestibular responses to linear acceleration are absent in otoconia-deficient C57BL/6JEi-het mice. Hear Res 135:56–60

Jones SM, Jones TA, Bell PL, Taylor MJ (2001) Compound gravity receptor polarization vectors evidenced by linear vestibular evoked potentials. Hear Res 154:54–61

Jones TA, Jones SM, Vijayakumar S, Brugeaud A, Bothwell M, Chabbert C (2011) The adequate stimulus for mammalian linear vestibular evoked potentials (VsEPs). Hear Res 280:133–140

Kato T, Shiraishi K, Eura Y, Shibata K, Sakata T, Morizono T, Soda T (1998) A ‘neural’ response with 3-ms latency evoked by loud sound in profoundly deaf patients. Audiol Neurootol 3:253–264

Kingma CM, Wit HP (2010) The effect of changes in perilymphatic K+ on the vestibular evoked potential in the guinea pig. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 267:1679–1684

Koyama H, Lewis ER, Leverenz EL, Baird RA (1982) Acute seismic sensitivity in the bullfrog ear. Brain Res 250:168–172

Lewis ER, Parnas BR (1994) Theoretical bases of short-latency spike volleys in the peripheral vestibular system. J Vestib Res 4:189–202

Murofushi T, Kaga K (2009) Vestibular evoked myogenic potential-its basics and clinical applications. Springer, Berlin

Murofushi T, Iwasaki S, Takai Y, Takegoshi H (2005) Sound-evoked neurogenic responses with short latency of vestibular origin. Clin Neurophysiol 116:401–405

Naganawa S, Sone M, Yamazaki M, Kawai H, Nakashima T (2011) Visualization of endolymphatic hydrops after intratympanic injection of Gd-DTPA: comparison of 2D and 3D real inversion recovery imaging. Magn Reson Med Sci 10:101–106

Ochi K, Ohashi T (2001) Sound-evoked myogenic potentials and responses with 3-ms latency in auditory brainstem response. Laryngoscope 111:1818–1821

Oei ML, Segenhout JM, Wit HP, Albers FW (2001) The vestibular evoked response to linear, alternating, acceleration pulses without acoustic masking as a parameter of vestibular function. Acta Otolaryngol 121:62–67

Papathanasiou ES, Lemesiou A, Hadjiloizou S, Myrianthopoulou P, Pantzaris M, Papacostas SS (2010) A new neurogenic vestibular evoked potential (N6) recorded with the use of air-conducted sound. Otol Neurotol 31:528–535

Plotnik M, Sichel JY, Elidan J, Honrubia V, Sohmer H (1999) Origins of the short latency vestibular evoked potentials (VsEPs) to linear acceleration impulses. Am J Otol 20:238–243

Rosengren SM, Welgampola MS, Colebatch JG (2010) Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials: past, present and future. Clin Neurophysiol 121:636–651

Rosengren SM, Govender S, Colebatch JG (2011) Ocular and cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potentials produced by air- and bone-conducted stimuli: comparative properties and effects of age. Clin Neurophysiol 122:2282–2289

Sakakura K, Miyashita M, Chikamatsu K, Takahashi K, Furuya N (2003) Tone burst-evoked myogenic potentials in rat neck extensor and flexor muscles. Hear Res 185:57–64

Schuknecht HF (1975) Pathophysiology of Meniere’s disease. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 8:507–514

Shojaku H, Zang RL, Tsubota M, Fujisaka M, Hori E, Nishijo H, Watanabe Y (2007) Effects of selective cochlear toxicity and vestibular deafferentation on vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in guinea pigs. Acta Otolaryngol 127:430–435

Stenfelt S, Goode RL (2005a) Bone-conducted sound: physiological and clinical aspects. Otol Neurotol 26:1245–1261

Stenfelt S, Goode RL (2005b) Transmission properties of bone conducted sound: measurements in cadaver heads. J Acoust Soc Am 118:2373–2391

Todd NP, Rosengren SM, Colebatch JG (2008) A source analysis of short-latency vestibular evoked potentials produced by air- and bone-conducted sound. Clin Neurophysiol 119:1881–1894

Uzun-Coruhlu H, Curthoys IS, Jones AS (2007) Attachment of the utricular and saccular maculae to the temporal bone. Hear Res 233:77–85

Valk WL, Wit HP, Albers FW (2006) Rupture of Reissner’s membrane during acute endolymphatic hydrops in the guinea pig: a model for Meniere’s disease? Acta Otolaryngol 126:1030–1035

Weisleder P, Jones TA, Rubel EW (1990) Peripheral generators of the vestibular evoked potentials (VsEPs) in the chick. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 76:362–369

Welgampola MS (2008) Evoked potential testing in neuro-otology. Curr Opin Neurol 21:29–35

Yang TH, Young YH (2005) Click-evoked myogenic potentials recorded on alert guinea pigs. Hear Res 205:277–283

Yang TH, Liu SH, Wang SJ, Young YH (2010) An animal model of ocular vestibular-evoked myogenic potential in guinea pigs. Exp Brain Res 205:145–152

Young ED, Fernandez C, Goldberg JM (1977) Responses of squirrel monkey vestibular neurons to audio-frequency sound and head vibration. Acta Otolaryngol 84:352–360

Acknowledgments

This study was supported through funds raised by the Ménière’s Research Fund Inc.—a charity organization, with funds maintained by The University of Sydney Medical Foundation. We would also like to acknowledge Em. Prof. Ian Curthoys’ support and advice throughout this study, in particular with issues relating to evoking and monitoring bone-conduction vibration stimulation in guinea pigs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Y. Chihara and D. J. Brown contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

221_2013_3602_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Figure S1: Example of a guinea pig skull bone. A. Surgical view of the dorsolateral approach for accessing the cochlea where the tympanic bulla has been opened just caudal to the ear canal. A recording wire has been inserted into the stylomastoid foramen leading to facial canal. B. Surgical view of dorsolateral approach exposing the semicircular canals. A small hole was made just rostral to the dorsolateral hole. C. Surgical view of the ventral approach for accessing whole cochlea and vestibule. (PDF 80 kb)

221_2013_3602_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Figure S2: Schematic representation of the technique for correcting the skull vibration. A. An initial 1 ms test impulse BCV stimulus was delivered to the B71. The acceleration of the animal’s skull was then measured in response to this impulse stimulus. By comparing the difference between the FFT of the BCV impulse and the FFT of the measured skull acceleration, we could derive a calibration curve in the frequency and time domain that could be used to correct the BCV impulse. This calibration curve could then be used to create a corrected BCV impulse-like stimulus which generated an impulse acceleration of the animal’s skull. FFT: Fast Fourier Transform, IFFT: Inverse FFT, LPF: Low-pass filter. B. Example waveforms of skull acceleration and jerk before and after the correction technique. We could get an impulse-like stimulus by using B71 bone vibrator. (PDF 275 kb)

Supplemental video 1: Cochlear destruction via a ventral approach. This procedure did not alter the VsEP waveform. (MPG 4902 kb)

Supplemental video 2: Saccular destruction via a ventral approach (after removing the cochlear and exposing the vestibule). This procedure did not alter the VsEP waveform. (MPG 3480 kb)

Supplemental video 3: Utricular destruction via a ventral approach (after destroying the cochlear and saccule). Destroying the posterior part of the utricle decreased the VsEP to the half its initial amplitude. Subsequent destruction of the anterior part of the utricle abolished VsEP completely. (MPG 6976 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chihara, Y., Wang, V. & Brown, D.J. Evidence for the utricular origin of the vestibular short-latency-evoked potential (VsEP) to bone-conducted vibration in guinea pig. Exp Brain Res 229, 157–170 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-013-3602-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-013-3602-5