Abstract

Summary

Antiresorptive treatment reduces the risk of fractures, but most patients remain at elevated risk. We used health registers to identify predictors of new major osteoporotic fractures in patients adhering to alendronate. Risk factors showed a different pattern than in the general population and included dementia, ulcer disease, and Parkinson’s disease.

Introduction

Antiresorptives reduce the excess risk of fractures in patients with osteoporosis, but most patients remain at elevated risk. In some countries, patients must sustain fractures while on bisphosphonate (BP) treatment to qualify for more expensive treatment. It is unclear if patients who fracture on BP can be viewed as a distinct subgroup.

Methods

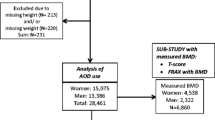

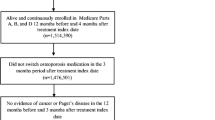

The National Prescription registry was used to identify 38,088 new alendronate users. The outcome was major osteoporotic fractures 6+ months after filling the first prescription in patients with a medication possession ratio > 80 %.

Results

One thousand and seventy-two (5.5 %) patients sustained major osteoporotic fractures. The risk increased with age and was lower in men. The most important risk factor was the number of comedications (hazard ratio (HR) 1.04, 95 % CI 1.03–1.06, for each drug). Dementia (HR 1.81, 95 % CI 1.18–2.78), prior fracture (one: HR 1.17, 95 % CI 1.02–1.34; multiple: HR 1.34, 95 % CI 1.08–1.67), and ulcer disease (HR 1.45, 95 % CI 1.04–2.03) also increased the risk. Diabetes did not influence fracture risk, nor did rheumatic disorders. The risk was lower in glucocorticoid users (HR 0.78, 95 % CI 0.65–0.93).

Conclusion

Risk factors while adhering to BP show a somewhat different pattern than that of the general population and FRAX. Ulcer disease and dementia may impair the ability to use the medications correctly. Though this is an observational study and associations may not be causal, it may be prudent to include dementia, ulcer disease, and Parkinson’s disease to capture the risk of fractures on treatment. Lower risk in patients treated with glucocorticoids and in men probably reflects a lower treatment threshold related to guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hochberg MC, Thompson DE, Black DM, Quandt SA, Cauley J, Geusens P et al (2005) Effect of alendronate on the age-specific incidence of symptomatic osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res 20:971–976

Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC et al (1996) Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Lancet 348:1535–1541

Liberman UA, Weiss SR, Broll J, Minne HW, Quan H, Bell NH et al (1995) Effect of oral alendronate on bone mineral density and the incidence of fractures in postmenopausal osteoporosis. The Alendronate Phase III Osteoporosis Treatment Study Group. N Engl J Med 333:1437–1443

Hosking D, Alonso CG, Brandi ML (2009) Management of osteoporosis with PTH: treatment and prescription patterns in Europe. Current Med Res Opin 25:263–270. doi:10.1185/03007990802645461

Clement FM, Harris A, Yong K, Lee KM, Manns BJ (2009) Using effectiveness and cost-effectiveness to make drug coverage decisions. JAMA 302:1437–1443

Leslie WD, Lix LM, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey E, Kanis JA (2012) Does osteoporosis therapy invalidate FRAX for fracture prediction? JBMR. doi:10.1002/jbmr.1582

Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, Applegate WB, Barrett-Connor E, Musliner TA et al (1998) Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA 280:2077–2082

Inderjeeth CA, Chan K, Kwan K, Lai M (2012) Time to onset of efficacy in fracture reduction with current anti-osteoporosis treatments. J Bone Miner Metab. doi:10.1007/s00774-012-0349-1

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC et al (2005) Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 43:1130–1139

Eastell R, Black DM, Boonen S, Adami S, Felsenberg D, Lippuner K et al (2009) Effect of once-yearly zoledronic acid five milligrams on fracture risk and change in femoral neck bone mineral density. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:3215–3225

Eastell R, Vrijens B, Cahall DL, Ringe JD, Garnero P, Watts NB (2011) Bone turnover markers and bone mineral density response with risedronate therapy: relationship with fracture risk and patient adherence. J Bone Min Res: Off J Am Soc Bone Min Res 26:1662–1669. doi:10.1002/jbmr.342

Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, Barrett-Connor E, Miller PD, Wehren LE et al (2004) Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med 164:1108–1112

Rejnmark L, Abrahamsen B, Ejersted C, Hyldstrup L, Jensen J-EB, Madsen OR, et al. The Danish Bone Society Osteoporosis Diagnosis and Treatment Guideline. Aarhus. 2009 Available: http://www.dkms.dk/vejledning/11_glukokort.htm. Accessed 16 Jun 2012

Rizzoli R, Cooper C, Reginster J-Y, Abrahamsen B, Adachi JD, Brandi ML et al (2012) Antidepressant medications and osteoporosis. Bone. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2012.05.018

Abrahamsen B, Brixen K (2009) Mapping the prescriptiome to fractures in men–a national analysis of prescription history and fracture risk. Osteoporos Int 20:585–597

Eom C-S, Lee H-K, Ye S, Park SM, Cho K-H (2012) Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JBMR 27:1186–1195. doi:10.1002/jbmr.1554

Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L (2008) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other antidepressants and risk of fracture. Calcif Tissue Int 82:92–101

Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L (2007) Fracture risk associated with parkinsonism and anti-Parkinson drugs. Calcif Tissue Int 81:153–161

Fink HA, Kuskowski MA, Orwoll ES, Cauley JA, Ensrud KE (2005) Association between Parkinson’s disease and low bone density and falls in older men: the osteoporotic fractures in men study. J Am Geriatr Soc 53:1559–1564

Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Eastell R (2011) Proton pump inhibitor use and the antifracture efficacy of alendronate. Arch Intern Med

Figura N, Gennari L, Merlotti D, Lenzi C, Campagna S, Franci B et al (2005) Prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection in male patients with osteoporosis and controls. Dig Dis Sci 50:847–852

Goerss JB, Kim CH, Atkinson EJ, Eastell R, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ III (1992) Risk of fractures in patients with pernicious anemia. J Bone Miner Res 7:573–579

Berry SD, Ngo L, Samelson EJ, Kiel DP (2010) Competing risk of death: an important consideration in studies of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 58:783–787. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02767.x

Rejnmark L, Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L (2005) Reduced fracture risk in users of thiazide diuretics. Calcif Tissue Int 76:167–175

Rejnmark L, Vestergaard P, Pedersen AR, Heickendorff L, Andreasen F, Mosekilde L (2003) Dose-effect relations of loop- and thiazide-diuretics on calcium homeostasis: a randomized, double-blinded Latin-square multiple cross-over study in postmenopausal osteopenic women. Eur J Clin Invest 33:41–50

Jamal SA, Hamilton CJ, Eastell R, Cummings SR (2011) Effect of nitroglycerin ointment on bone density and strength in postmenopausal women: a randomized trial. JAMA 305:800–807

Rejnmark L, Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L (2006) Decreased fracture risk in users of organic nitrates: a nationwide case-control study. J Bone Miner Res 21:1811–1817

Pouwels S, Lalmohamed A, van Staa T, Cooper C, Souverein P, Leufkens HG et al (2010) Use of organic nitrates and the risk of hip fracture: a population-based case-control study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:1924–1931. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2342

Vasikaran S, Cooper C, Eastell R, Griesmacher A, Morris HA, Trenti T et al (2011) International Osteoporosis Foundation and International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine position on bone marker standards in osteoporosis. Clin Chem Lab Med 49:1271–1274

Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, Prince R, Gaich GA, Reginster JY et al (2001) Effect of parathyroid hormone (1-34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 344:1434–1441

Laurs-van Geel TACM, Center JR, Geusens PP, Dinant G-J, Eisman JA (2010) Clinical fractures cluster in time after initial fracture. Maturitas 67:339–342. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.09.002

Conflicts of interest

B. Abrahamsen serves on advisory boards for Nycomed and Amgen and has received grant or research support from Novartis, Nycomed, Amgen, and Merck and speaker fees from Nycomed, Merck, Eli Lilly, and Amgen. KH Rubin has no disclosures. P. Eiken has received grant/research support from Nycomed, Amgen, and Novartis and is on Speakers Bureau with Nycomed, Novartis, GSK, and Eli Lilly. R. Eastell serves as a consultant, has received honoraria for speaking, and has received grant support from Amgen, AstraZeneca, California Pacific Medical Center, GlaxoSmithKline, Hologic, Kyphon Inc., Lilly Industries, Maxygen, Nastech Pharmaceuticals, Nestle Research Center, New Zealand Milk Limited, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, ONOPharma, Organon Laboratories, Osteologix, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Roche Diagnostics, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Shire, Tethys, Trans-Pharma Medical Limited, Unilever, and Unipath. This study did not receive outside funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abrahamsen, B., Rubin, K.H., Eiken, P.A. et al. Characteristics of patients who suffer major osteoporotic fractures despite adhering to alendronate treatment: a National Prescription registry study. Osteoporos Int 24, 321–328 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2184-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2184-6