Abstract

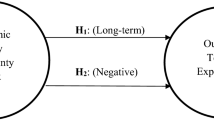

This paper analyses the effects of the shadow economy on the total tourism spending of citizens for 84 countries from 1995 to 2017. The empirical framework is that of panel quantile regression with fixed effects. We also analyse the simultaneous effects of the shadow economy on domestic and outbound tourism spending using seemingly unrelated regressions. We first show that increases in the shadow economy appear to reduce total tourism spending: the increases are less dominant in countries with higher levels of travel activities. Moreover, the shadow economy negatively affects domestic and outbound tourism spending in the global sample, while different effects exist in subsamples. Lastly, we show that for the two sub-periods (1995–2007 and 2008–2017), the effects of the shadow economy on total tourism spending are mostly consistent in both periods except for statistically insignificant effects in the case of low- and lower-middle-income countries. The effects of the shadow economy on domestic and outbound tourism are also consistent in the two periods. However, the shadow economy exerted a significant positive impact on outbound tourism for upper-middle-income countries after the 2008 global financial crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data can be provided upon reasonable requests.

Code availability

Code can be provided upon reasonable request.

Notes

Results were calculated by the author(s) from the tourism spending data of every economy from the World Travel and Tourism Council (real values). Tourism consumption in 2020 dropped severely due to the COVID-pandemic and may not fully reflect the size of tourism markets for the period 1995–2019; thus, we do not present this here.

More detail about the structural quantile functions (or the instrumental variable quantile regression) can be found on page 17 and in Table 10, Appendix.

It is worth noting that these databases contain some of the most reliable data on the shadow economy.

We are thankful to an anonymous reviewer for their helpful comment.

The price level in the destination country is more important for decision-making by tourists undertaking outbound travel. However, this study focuses on the aggregate data for outbound tourism spending rather than bilateral tourism spending. Therefore, we use domestic price levels in the function of outbound tourism spending with the implication that an increase in domestic price levels would raise the relative price of domestic tourism services in comparison with outbound travel. The increase in relative price would then motivate tourists to choose outbound travel in exchange for domestic travel. We appreciate a helpful comment from an anonymous reviewer on this point.

Tourists’ travel decisions are linked strongly to their income (in an aggregate manner, GDP); and the literature of the shadow economy indicates that informal economic activities are a pervasive sector in the process of economic development (Medina and Schneider 2019).

This study performed the panel Granger non-causality test by Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012) to examine statistical causality between the shadow economy and tourism spending. The results can be provided upon request. The results imply that there may be statistical evidence of mutual causality between the shadow economy and tourism spending.

We ran 20 bootstrap replications.

It is important to note that the data for tax complexity were only available for 2016, 2018, and 2020, while data on the percentages of the population who borrowed from a formal financial institution were also missing for several countries. Therefore, we only included these analyses for robustness checks. We appreciate the thoughtful comment from an anonymous reviewer.

Total tourism spending is the sum of domestic and outbound tourism spending.

Since international travel also uses the services of domestic tourism businesses.

References

Adams KM, Choe J, Mostafanezhad M, Phi GT (2021) (Post-) pandemic tourism resiliency: Southeast Asian lives and livelihoods in limbo. Tour Geogr. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2021.1916584

Adriana D (2014) Revisiting the relationship between unemployment rates and shadow economy. a Toda-Yamamoto approach for the case of Romania. Procedia Econ Financ 10:227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00297-4

Agbola FW, Dogru T, Gunter U (2020) Tourism demand: emerging theoretical and empirical issues. Tour Econ 26(8):1307–1310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816620956747

Aguiló E, Rosselló J, Vila M (2017) Length of stay and daily tourist expenditure: a joint analysis. Tour Manag Perspect 21:10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2016.10.008

Aradhyula S, Tronstad R (2003) Does tourism promote cross-border trade? Am J Agr Econ 85(3):569–579

Arlt WG (2013) The second wave of chinese outbound tourism. Tour Plan Dev 10(2):126–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2013.800350

Athanasopoulos G, Deng M, Li G, Song H (2014) Modelling substitution between domestic and outbound tourism in Australia: a system-of-equations approach. Tour Manage 45:159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.03.018

Awasthi R, Engelschalk M (2018) Taxation and the shadow economy: how the tax system can stimulate and enforce the formalization of business activities. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. Washigton, D.C., US: World Bank

Barham BL, Melo AP, Hertz T (2020) Earnings, wages, and poverty outcomes of US farm and low-skill workers. Appl Econ Perspect Policy 42(2):307–334

Baruah B (2004) Earning their keep and keeping what they earn: a critique of organizing strategies for South Asian women in the informal sector. Gend Work Organ 11(6):605–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2004.00251.x

Berdiev AN, Saunoris JW (2016) Financial development and the shadow economy: a panel VAR analysis. Econ Model 57:197–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2016.03.028

Berdiev AN, Goel RK, Saunoris JW (2018) Corruption and the shadow economy: one-way or two-way street? The World Economy 41(11):3221–3241. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12661

Bookman M (2007) Medical tourism in developing countries. Springer, Berlin, Germany

Brau R, Maria Pinna A (2013) Movements of people for movements of goods? The World Economy 36(10):1318–1332

Brida JG, Scuderi R (2013) Determinants of tourist expenditure: a review of microeconometric models. Tour Manag Perspect 6:28–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2012.10.006

Buckley R, Gretzel U, Scott D, Weaver D, Becken S (2015) Tourism megatrends. Tour Recreat Res 40(1):59–70

Buehn A, Schneider F (2012) Shadow economies around the world: novel insights, accepted knowledge, and new estimates. Int Tax Public Financ 19(1):139–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-011-9187-7

Bulut U, Kocak E, Suess C (2020) The effect of freedom on international tourism demand: empirical evidence from the top eight most visited countries. Tour Econ 26(8):1358–1373. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816619896957

Canh PN, Schinckus C, Dinh Thanh S (2021) What are the drivers of shadow economy? A further evidence of economic integration and institutional quality. J Int Trade Econ Dev 30(1):47–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2020.1799428

Chernozhukov V, Hansen C (2008) Instrumental variable quantile regression: a robust inference approach. J Econ 142(1):379–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2007.06.005

Choi JP, Thum M (2005) Corruption and the shadow economy. Int Econ Rev 46(3):817–836

Claveria O, Poluzzi A (2016) Tourism trends in the world's main destinations before and after the 2008 financial crisis using UNWTO official data. Data Brief 7:1063–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2016.03.043

Din BH, Habibullah MS, Baharom AH, Saari MD (2016) Are shadow economy and tourism related? International evidence. Procedia Econ Financ 35:173–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(16)00022-8

Dixit SK (2020) Tourism in India, vol 31. Taylor & Francis, USA, pp 177–180

Dreher A, Kotsogiannis C, McCorriston S (2009) How do institutions affect corruption and the shadow economy? Int Tax Public Financ 16(6):773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-008-9089-5

Elgin C, Oztunali O (2014) Pollution and informal economy. Econ Syst 38(3):333–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2013.11.002

Enste DH (2018) The shadow economy in OECD and EU accession countries–empirical evidence for the influence of institutions, liberalization, taxation and regulation. In: Bajada C, Schneider F (eds) Size, causes and consequences of the underground economy: an international perspective. Routledge, London, UK, pp 123–138

Eugenio-Martin JL (2003) Modelling determinants of tourism demand as a five-stage process: a discrete choice methodological approach. Tour Hosp Res 4(4):341–354

Farzanegan MR, Gholipour HF, Feizi M, Nunkoo R, Andargoli AE (2020) International tourism and outbreak of coronavirus (COVID-19): a cross-country analysis. J Travel Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520931593

Fishbein M, Ajzen E (1975) Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley

Gao J, Zeng X, Zhang C, Porananond P (2022) Understanding the young middle-class Chinese outbound tourism consumption: a social practice perspective. Tour Manag 92:104555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104555

Gillanders R, Parviainen S (2018) Corruption and the shadow economy at the regional level. Rev Dev Econ 22(4):1729–1743. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12517

Goel RK, Saunoris JW, Schneider F (2019) Growth in the shadows: effect of the shadow economy on US economic growth over more than a century. Contemp Econ Policy 37(1):50–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12288

Goel RK, Saunoris JW (2014) Global corruption and the shadow economy: spatial aspects. Public Choice 161(1):119–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0135-1

Goel RK, Saunoris JW (2019) Does variability in crimes affect other crimes? The case of international corruption and shadow economy. Appl Econ 51(3):239–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2018.1494378

Goh E, King B (2020) Four decades (1980–2020) of hospitality and tourism higher education in Australia: developments and future prospects. J Hosp Tour Educ 32(4):266–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/10963758.2019.1685892

Gómez-Déniz E, Pérez-Rodríguez JV (2019) Modelling distribution of aggregate expenditure on tourism. Econ Model 78:293–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2018.09.027

Gundelfinger-Casar J, Coto-Millán P (2018) Measuring the main determinants of tourism flows to the Canary Islands from mainland Spain. J Air Transp Manag 70:83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2018.05.002

Hajilee M, Stringer DY, Hayes LA (2021) On the link between the shadow economy and stock market development: an asymmetry analysis. Q Rev Econ Financ 80:303–316

Hajilee M, Stringer DY, Metghalchi M (2017) Financial market inclusion, shadow economy and economic growth: new evidence from emerging economies. Q Rev Econ Financ 66:149–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2017.07.015

Hao L, Naiman DQ (2007) Quantile regression. Thousand Oaks, California

Huang S, Keating BW, Kriz A, Heung V (2015) Chinese outbound tourism: an epilogue. J Travel Tour Mark 32(1–2):153–159

Johnson P, Thomas B (1990) Employment in tourism: a review. Ind Relat J 21(1):36–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2338.1990.tb00085.x

Kaosa-ard M, Bezic D, White S (2013) Domestic tourism in Thailand: supply and demand. The native tourist Routledge, USA, pp 123–155

Keum K (2010) Tourism flows and trade theory: a panel data analysis with the gravity model. Ann Reg Sci 44(3):541–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-008-0275-2

Khan H, Toh RS, Chua L (2005) Tourism and trade: cointegration and granger causality tests. J Travel Res 44(2):171–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505276607

Khoshnevis Yazdi S, Khanalizadeh B (2017) Tourism demand: a panel data approach. Curr Issue Tour 20(8):787–800. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1170772

Koenker R, Bassett G (1978) Regression quantiles. Econometrica 46(1):33–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/1913643

Kulendran N, Wilson K (2000) Is there a relationship between international trade and international travel? Appl Econ 32(8):1001–1009. https://doi.org/10.1080/000368400322057

Liverani M, Ir P, Jacobs B, Asante A, Jan S, Leang S et al (2020) Cross-border medical travels from Cambodia: pathways to care, associated costs and equity implications. Health Policy Plan 35(8):1011–1020. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czaa061

Ma JX, Buhalis D, Song H (2003) ICTs and Internet adoption in China’s tourism industry. Int J Inf Manage 23(6):451–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2003.09.002

Machado JAF, Santos Silva JMC (2019) Quantiles via moments. J Econ 213(1):145–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2019.04.009

Markina IA, Sharkova AV, Barna MY (2018) Entrepreneurship in the shadow economy: the case study of Russia and Ukraine. Int J Entrep 22(3):1–13

Martin CA, Witt SF (1987) Tourism demand forecasting models: choice of appropriate variable to represent tourists’ cost of living. Tour Manag 8(3):233–246

Martins LF, Gan Y, Ferreira-Lopes A (2017) An empirical analysis of the influence of macroeconomic determinants on world tourism demand. Tour Manage 61:248–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.01.008

McKercher B (2008) Segment transformation in urban tourism. Tour Manage 29(6):1215–1225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.03.005

Medina L, Schneider F (2018) Shadow economies around the world: what did we learn over the last 20 years? IMF working paper. Washington, D.C., US: IMF.

Medina L, Schneider F (2019) Shedding light on the shadow economy: a global database and the interaction with the official one. CESifo working papers. Munich, Germany: Munich Society for the Promotion of Economic Research -CESifo-GmbH.

Mora-Rivera J, García-Mora F (2021) International remittances as a driver of domestic tourism expenditure: evidence from Mexico. J Travel Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520962222

Mora-Rivera J, Cerón-Monroy H, García-Mora F (2019) The impact of remittances on domestic tourism in Mexico. Ann Tour Res 76:36–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.03.002

Nguyen CP (2021) Do institutions matter for tourism spending? Tour Econ. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548166211045847

Nguyen CP, Schinckus C, Su TD (2020b) Economic policy uncertainty and demand for international tourism: an empirical study. Tour Econ 26(8):1415–1430. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816619900584

Nguyen CP, Thanh SD, Nguyen B (2020c) Economic uncertainty and tourism consumption. Tour Econ. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816620981519

Nguyen CP, Su TD (2021) The vulnerability effect of international tourism on a destination’s Economy. Tour Plan Dev. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2021.1958916

Nguyen CP, Binh PT, Su TD (2020) Capital investment in tourism: a global investigation. Tour Plan Dev. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2020.1857825

Njindan Iyke B, Ho S-Y (2018) Real exchange rate volatility and domestic consumption in Ghana. J Risk Financ 19(5):513–523. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRF-01-2017-0010

Papatheodorou A (1999) The demand for international tourism in the Mediterranean region. Appl Econ 31(5):619–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/000368499324066

Park S, Woo M, Nicolau JL (2020) Determinant factors of tourist expenses. J Travel Res 59(2):267–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519829257

Phuc NC, Christophe S, Thanh DS (2022) The determinants of outbound tourism: a revisit of socioeconomic and environmental conditions. Tourism Analysis (in press)

Poliquin CW (2018) The Effect of the Internet on Wages. University of California working paper

Powell D (2016) Quantile regression with nonadditive fixed effects. Quantile treatment effects, http://works.bepress.com/david_powell/1/

Rogerson CM (2015) Unpacking business tourism mobilities in sub-Saharan Africa. Curr Issue Tour 18(1):44–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.898619

Roodman D (2009) How to do xtabond2: an introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. Stand Genomic Sci 9(1):86–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0900900106

Santana-Gallego M, Ledesma-Rodríguez FJ, Pérez-Rodríguez JV (2010) Exchange rate regimes and tourism. Tour Econ 16(1):25–43. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000010790872015

Santana-Gallego M, Ledesma-Rodríguez FJ, Pérez-Rodríguez JV (2016) International trade and tourism flows: an extension of the gravity model. Econ Model 52:1026–1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2015.10.043

Schneider F (2015a) Shadow economy and tax evasion in the EU. J Money Laund Control 18(1):34–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMLC-09-2014-0027

Schneider F, Enste DH (2000) Shadow economies: size, causes, and consequences. J Econ Lit 38(1):77–114. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.38.1.77

Schneider F, Kearney A (2013) The shadow economy in Europe. Johannes Kepler Universitat, Linz

Schneider F, Williams C (2013) The shadow economy. The Institute of Economic Affairs, Edward Elgar

Schneider F (2015b) Size and development of the shadow economy of 31 European and 5 Other OECD countries from 2003 to 2014: different developments?. J Self-Gov Manag Econ 3(4):7–29

Sinha A, Sengupta T, Mehta A (2021) Tourist arrivals and shadow economy: wavelet-based evidence from Thailand. Tour Anal Press. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354221X16186396395764

Smeral E (2010) Impacts of the world recession and economic crisis on tourism: forecasts and potential risks. J Travel Res 49(1):31–38

Suresh KG, Tiwari AK (2018) Does international tourism affect international trade and economic growth? Indian Exp Empir Econ 54(3):945–957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-017-1241-6

Thrane C (2015) Students’ summer tourism: an econometric analysis of trip costs and trip expenditures. Tour Manag Perspect 15:65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.03.012

Torgler B, Schneider F (2009) The impact of tax morale and institutional quality on the shadow economy. J Econ Psychol 30(2):228–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2008.08.004

Van Dao T (2011) A review of tourism in Southeast Asia: challenges and new directions. J Sustain Tour 19(6):792–795. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2010.542648

van Nuenen T, Scarles C (2021) Advancements in technology and digital media in tourism. Tour Stud 21(1):119–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797621990410

Vousinas Georgios L (2017) Shadow economy and tax evasion. the achilles heel of Greek economy. determinants, effects and policy proposals. J Money Laund Control 20(4):386–404. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMLC-11-2016-0047

Vujko A, Tretiakova TN, Petrovic MD, Radovanovic M, Gajic T, Vukovic D (2019) Women’s empowerment through self-employment in tourism. Ann Tour Res 76:328–330

Weaver A (2021) Tourism, big data, and a crisis of analysis. Ann Tour Res 88:103158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103158

WTTC (2020) Travel & tourism economic impact 2019. In: GG Manzo (Ed.). London SE1 0HR, United Kingdom: World Travel & Tourism Council

Wu T-P, Wu H-C, Wu S-T, Wu Y-Y (2020) Economic policy uncertainty and tourism Nexus dynamics in the G7 countries: further evidence from the wavelet analysis. Tour Plan Dev. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2020.1825520

Wu T-P, Wu H-C (2021) Global economic policy uncertainty and tourism of fragile five countries: evidence from time and frequency approaches. J Travel Res 60(5):1061–1073. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520921245

Zellner A (1962) An efficient method of estimating seemingly unrelated regressions and tests for aggregation bias. J Am Stat Assoc 57(298):348–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1962.10480664

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers who kindly reviewed this paper and provided valuable suggestions and comments. We also greatly appreciate the insightful comments on previous versions of this paper provided by Professor Gabriel S. Lee (University of Regensburg, Germany).

Funding

The study is funded by the University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City (UEH), Vietnam.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CPN contributed to conceptualization, methodology, data curation, validation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, and writing—reviewing and editing; BQN contributed to data curation, robustness analysis, and writing—reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, C.P., Nguyen, B.Q. Does the shadow economy matter for tourism consumption? New global evidence. Empir Econ 65, 729–773 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-022-02354-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-022-02354-x