Abstract

This paper tries to identify a chronology for the Portuguese business cycle and test for the presence of duration dependence in the respective phases of expansion and contraction. A duration-dependent Markov-switching vector autoregressive model is employed in that task. This model is estimated over year-on-year growth rates of a set of relevant economic indicators, namely industrial production, a composite leading indicator and, additionally, civilian employment. The estimated specifications allow us to identify four main periods of contraction during the last three decades and some evidence of positive duration dependence in contractions, but not in expansions, especially when employment is added to the model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For further details contact the NBER at http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html.

For further details contact the ECRI at http://www.businesscycle.com/resources/cycles/ and the CEPR at http://www.cepr.org/data/Dating/.

Another basic procedure to date the business cycle is the algorithm proposed by Bry and Boschan (1971) to pin-point the relevant turning points in a data series. However, it presents an important drawback: it is only applicable to a single monthly series. Harding and Pagan (2002) solves part of the problem extending the algorithm to quarterly data, but its application remains restricted to a single series. An even simpler procedure is the GDP growth rule, which defines a recession as a period of negative growth of real GDP that lasts two or more consecutive quarters. But, once again, it only relies on a single series which means that not all relevant information is considered. Hence, these two procedures may not be able to capture the true underlying business cycle.

For a detailed explanation on how the Gibbs sampler is implemented to the DDMSVAR model, see Pelagatti (2002, 2003). To estimate the unknown MSVAR parameters, Durland and McCurdy (1994) use a quasi-maximum likelihood estimator, while Kim and Nelson (1998) and Pelagatti (2002, 2003) employ the Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method. An interesting analysis of several specifications and estimations of the MS model can be found in Kim and Nelson (1999).

We would like to thank Matteo Pelagatti for making his DDMSVAR code for Ox publicly available in his website: http://www.statistica.unimib.it/utenti/p_matteo/.

See also the extension to the Turkish economy provided by Ozun and Turk (2009).

Monthly data are also available for sales, but this series starts only in the mid-1990s.

For further details on the components of the \(CLI\) and on the methodology to compute it, contact the OECD directly at http://www.oecd.org/std/cli. The source for the data used in this analysis is OECD, Main Economic Indicators, February 2011.

An alternative would be to rely on the fluctuation of GNP or GDP series—like Pelagatti (2001) and Chen and Shen (2006)—but the available quarterly data for these series for Portugal start only in 1996. Despite the small sample period, some attempts were made, but the model did not work well: expansions and contractions were not clearly identifiable. The same happened when \(IP\) was the only series used in the model.

There, we also find information for the annual growth rate of civilian employment. Monthly data for employment were obtained by linear interpolation of the available quarterly data for the period 1983–2010.

The OECD calls to \(dlCLI\) the year-on-year growth rate of the \(CLI\) and considers it as the preferred pointer to identify turning points because it is less volatile and provides earlier and clearer signals for their identification than the \(CLI\) itself.

As in Pelagatti (2003, p. 15), we argue that this is probably due to the fact that the DDMS model is a stationary process, which can then be approximated with an autoregressive model. Hence, the duration-dependent switching part and the VAR part try to explain almost the same features of the series and the model is not too well identified.

The Gibbs sampler always reached convergence to its stationary distribution. To save space, their graphs are not presented here, but they are available upon request. The same applies to the kernel density estimates/distributions of \(\varvec{\mu }\) and \(\varvec{\beta }\).

For a 90 %-confidence interval that is no longer the case.

However, we will see below that the additional information contained in the (annual growth rate of the) employment variable will be helpful in unveiling the presence of positive duration dependence in contractions.

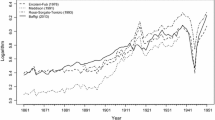

Note that, in Fig. 1, the mean of the transition probability of moving into a contraction after a period of expansion, i.e. \(Pr(S_{t}=0|S_{t-1}=1,D_{t-1}=d)\), is flat.

For details on how these probabilities are computed, please see Pelagatti’s (2003) code.

Note that our chronology also identifies reasonably well the two periods of low growth pointed out by Dias (2003) for the first half of the 1980s and 1990s.

The Golf War, the German reunification and the problems with the European Exchange Rate Mechanisms also contributed, in some degree, to the international recession.

See Table 1 for descriptive statistics.

Other priors were tried but results were quite similar. Those results are available upon request. This specification also considers \(\tau =60\) and \( p=0 \), and the Gibbs sampler was run for the same number of interactions as the other estimations presented above.

Several combinations of annual and monthly growth rates of \(IP\), \(CLI\) and \( Emp\) were also tried, but results and conclusions regarding the presence of duration dependence and the respective business cycle chronology remained practically the same. In particular, when only monthly growth rates of those three variables are used, results are quite similar to the ones presented, in first place, in this section. The problem is that the time period is shorter, which means that the contraction in 1983 is missed. All those estimations and results are not reported here due to space limitations, but they are available upon request.

References

Afonso A, Claeys P, Sousa R (2011) Fiscal regime shifts in Portugal. Port Econ J 10:83–108

Agnello L, Sousa R (2011) Can fiscal stimulus boost economic recovery? Revue Économique 62(6): 1045–1066

Agnello L, Sousa R (2013) Fiscal policy and asset prices. Bull Econ Res 65(2):154–177

Agnello L, Schuknecht L (2011) Booms and busts in housing markets: determinants and implications. J Hous Econ 20(3):171–190

Artis M, Krolzig H-M, Toro J (2004) The European business cycle. Oxf Econ Pap 56:1–44

Bry G, Boschan C (1971) Cyclical analysis of time series: selected procedures and computer program. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York

Burns A, Mitchell W (1946) Measuring business cycles. NBER Studies in Business Cycles, No. 2. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York

Castro V (2010) The duration of economic expansions and recessions: more than duration dependence. J Macroecon 32:347–365

Cavalcanti T (2007) Business cycle and level accounting: the case of Portugal. Port Econ J 6:47–64

Chen S, Shen C (2006) Is there a duration dependence in Taiwan’s business cycles. Int Econ J 20:109–127

Correia I, Neves J, Rebelo S (1992) Business cycles in Portugal: theory and evidence. In: Amaral JF, Lucena D, Mello AS (eds) The Portuguese economy towards 1992. Kluwer, Boston, pp 1–64

Davig T (2007) Change-points in US business cycle durations. Stud Nonlinear Dyn Econ 11(2), 1–21

Dias F (2003) Nonlinearities over the business cycle: an application of the smooth transition autoregressive model to characterize GDP dynamics for the Euro-Area and Portugal. Working Paper WP 9-03, Bank of Portugal

Dias M (1997) Analise da Evolução Ciclica da Economia Portuguesa no Periodo de 1953 a 1993. Bank of Portugal, Economic Bulletin, September 1997, pp 77–83

Diebold F, Rudebusch G, Sichel D (1990) International evidence on business cycle duration dependence. Institute for Empirical Macroeconomics, DP 31

Diebold F, Rudebusch G, Sichel D (1993) Further evidence on business cycle duration dependence. In: Stock JH, Watson MW (eds) Business cycles, indicators, and forecasting. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 87–116

Durland M, McCurdy T (1994) Duration-dependent transitions in a Markov model of US GNP growth. J Bus Econ Stat 12:279–288

Fisher I (1925) Our unstable dollar and the so-called business cycle. J Am Stat Assoc 20:179–202

Hamilton J (1989) A new approach to the economic analysis of nonstationary time series and the business cycle. Econometrica 57:357–384

Harding D, Pagan A (2002) Dissecting the cycle: a methodological investigation. J Monet Econ 49:365–381

Kim C, Nelson C (1998) Business cycle turning points, a new coincident index, and tests of duration dependence based on a dynamic factor model with regime switching. Rev Econ Stat 80:188–201

Kim C, Nelson C (1999) State space models with regime switching: classical and GIBBS-sampling approaches with applications. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Krolzig H-M (1997) Markov-switching vector autoregressions. Modelling, statistical inference and application to business cycle analysis. Springer, Berlin

Krolzig H-M (2001) Markov-switching procedures for dating the Euro-Zone business cycle. Q J Econ Res 70:339–351

Krolzig H-M, Toro J (2005) Classical and modern business cycle measurement: the European case. Span Econ Rev 7:1–21

Layton A, Smith D (2007) Business cycle dynamics with duration dependence and leading indicators. J Macroecon 29:855–875

Mallick S, Sousa R (2013) The real effects of financial stress in the Euro zone. Int Rev Financ Anal 30:1–17

Neves J (1994) The Portuguese economy: a picture in figures. Portuguese Catholic University, Lisbon

Neves P, Belo F (2002) Evolução Ciclica da Economia Portuguesa no Periodo de 1910 a 1958: uma breve analise. Bank of Portugal, Economic Bulletin, pp 57–69

Ozun A, Turk M (2009) A duration-dependent regime switching model for an open emerging economy. Rom J Econ Forecast 4:66–81

Pelagatti M (2001) Gibbs sampling for a duration dependent Markov-switching model with application to the US business cycle. Working Paper, Quaderno di Dipartimento QD2001/2 (March), Dipartimento di Statistica, Universita degli Studi di Milano Bicocca

Pelagatti M (2002) Duration-dependent Markov-switching VAR models with applications to the business cycle analysis. In: Proceedings of the XLI scientific meeting of the Italian statistics society

Pelagatti M (2003) DDMSVAR for Ox: a software for time-series modeling with duration-dependent Markov-switching autoregressions. 1st OxMetrics User Conference, London

Sichel D (1991) Business cycle duration dependence: a parametric approach. Rev Econ Stat 73:254–260

Schirwitz B (2009) A comprehensive German business cycle chronology. Empir Econ 37:287–301

Sousa R (2010) Housing wealth, financial wealth, money demand and policy rule: evidence from the euro area. N Am J Econ Financ 21(1):88–105

Zuehlke T (2003) Business cycle duration dependence reconsidered. J Bus Econ Stat 21:564–569

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the participants at the 5th Annual Meeting of the Portuguese Economic Journal, University of Aveiro, 8–9 July 2011, for their most interesting comments and suggestions. The author also thanks the financial support provided by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology under research Grant PEst-C/EGE/UI3182/2011 (partially funded by COMPTE, QREN and FEDER).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Castro, V. The Portuguese business cycle: chronology and duration dependence. Empir Econ 49, 325–342 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-014-0860-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-014-0860-4