Abstract

Purpose

The effect of the routine use of a stylet during tracheal intubation on first-attempt intubation success is unclear. We hypothesised that the first-attempt intubation success rate would be higher with tracheal tube + stylet than with tracheal tube alone.

Methods

In this multicentre randomised controlled trial, conducted in 32 intensive care units, we randomly assigned patients to tracheal tube + stylet or tracheal tube alone (i.e. without stylet). The primary outcome was the proportion of patients with first-attempt intubation success. The secondary outcome was the proportion of patients with complications related to tracheal intubation. Serious adverse events, i.e., traumatic injuries related to tracheal intubation, were evaluated.

Results

A total of 999 patients were included in the modified intention-to-treat analysis: 501 (50%) to tracheal tube + stylet and 498 (50%) to tracheal tube alone. First-attempt intubation success occurred in 392 patients (78.2%) in the tracheal tube + stylet group and in 356 (71.5%) in the tracheal tube alone group (absolute risk difference, 6.7; 95%CI 1.4–12.1; relative risk, 1.10; 95%CI 1.02–1.18; P = 0.01). A total of 194 patients (38.7%) in the tracheal tube + stylet group had complications related to tracheal intubation, as compared with 200 patients (40.2%) in the tracheal tube alone group (absolute risk difference, − 1.5; 95%CI − 7.5 to 4.6; relative risk, 0.96; 95%CI 0.83–1.12; P = 0.64). The incidence of serious adverse events was 4.0% and 3.6%, respectively (absolute risk difference, 0.4; 95%CI, − 2.0 to 2.8; relative risk, 1.10; 95%CI 0.59–2.06. P = 0.76).

Conclusions

Among critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation, using a stylet improves first-attempt intubation success.

Similar content being viewed by others

In this randomized clinical trial that included 999 patients, the use of a stylet for tracheal intubation in critically ill adult patients resulted in significantly higher first-attempt intubation success than the use of tracheal tube alone. The incidence of serious adverse events evaluated by the rate of traumatic injuries related to tracheal intubation was similar in the two groups. |

Introduction

Acute respiratory failure is among the leading causes of intensive care unit (ICU) admission and tracheal intubation for invasive mechanical ventilation in adult patients [1]. The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has further highlighted the importance of understanding the best approach to providing tracheal intubation for critically ill patients [2, 3].

Complications related to tracheal intubation are higher in ICU than in operating room [4, 5] because of anatomical difficulty, physiological difficulty such as pre-existing hypoxia and haemodynamic instability and logistical difficulty. First-attempt intubation success [6, 7] is associated with reduced likelihood of complications related to tracheal intubation [1, 6] and reduce the time needed for intubation, thus reducing exposure time of the healthcare worker to potential pathogens. Various devices and strategies aiming at increasing first-attempt intubation success in critically ill patients and at decreasing the complications related to tracheal intubation have been assessed in recent times [6,7,8,9]. In 2019, a multicentre randomised trial [10] suggested that bag-mask ventilation during tracheal intubation of critically ill adults prevented hypoxemia and reported a first-attempt intubation success rate of 81%. A 60–85% of first-attempt intubation success rate and a 30– 60% complications rate observed across studies [1, 8, 10,11,12] highlight the importance of improving the safety and efficiency of tracheal intubation [13, 14].

The most widely used method for tracheal intubation in critically ill patients involves using an endotracheal tube alone [15]. Alternatively, an endotracheal tube with an intubating stylet has been proposed to facilitate tracheal tube insertion, when difficulty is encountered in the passage of the endotracheal tube, with the aim of reducing complications [16]. Some authors suggested that using a preshaped tracheal tube with stylet may increase first-attempt intubation success [16]. However, some traumatic injuries with stylets have been reported including mucosal bleeding, perforation of the trachea or oesophagus and sore throat [16,17,18]. While intubation stylets have been used for decades in emergency airway management, the effect of the routine use of a stylet during tracheal intubation on first-attempt intubation success is unclear [19,20,21]. Therefore, whether the systematic use of a stylet for first-attempt intubation in the ICU is of greater benefits to patients deserves investigation.

To determine the effect of using an intubating stylet on first-attempt intubation success during tracheal intubation of critically ill adults, we conducted the STYLET for Orotracheal intubation (STYLETO) trial. We hypothesized that, as compared with tracheal tube alone, the use of a stylet would significantly increase the first-attempt intubation success rate.

Material and methods

Study design

From October 1, 2019, to March 17, 2020, we conducted a multicentre, parallel-group, unblinded, pragmatic, randomised trial comparing tracheal tube plus stylet with tracheal tube alone (i.e. without stylet) during tracheal intubation of critically ill adults. The trial was approved for all centres by a central Ethics Committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Nord-Ouest, France, 2019-A01180-57) according to French law. An informed consent was required. The STYLETO trial was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov with trial identification number NCT04079387 before the first inclusion in the trial. The protocol and statistical analysis plan were published before the conclusion of enrolment [22].

Patients

The trial was conducted in 32 ICUs in 30 university and 2 non-university French hospitals, without any selection criteria. Patients were eligible for participation in the trial if they were older than 18 years of age, covered by public health insurance, provided written informed consent from the patient or proxy (if present) before inclusion or once possible when patient has been included in a context of emergency and require mechanical ventilation in ICU through an endotracheal tube. Patients were excluded if they underwent a tracheal intubation following a cardiac arrest or during the same ICU stay with previous inclusion in the study (electronic supplementary material).

Randomisation and blinding

Patients underwent central randomisation in a 1:1 ratio to receive either tracheal tube + stylet or tracheal tube alone in blocks of variable sizes, with the use of a computer-generated and blinded assignment sequence, stratified according to trial site.

The central randomization was electronic, obtained after connexion to a website and directly communicated via the website, without any need to contact the coordinating centre. The randomisation was concealed using a method of minimisation [23]. Treatment assignments were concealed from patients, research staff and the statistician. The masking was done by asking to all the centres to collect data by the research staff not performing intubation, and therefore not aware of the group of assignment.

Procedures

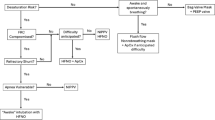

The first attempt at laryngoscopy was performed with a standard Macintosh laryngoscope. In the tracheal tube + stylet group, the trachea was intubated with a tracheal tube + stylet with a straight-to-cuff stylet with a bend angle of 25° to 35° at the distal tip within the tracheal tube [16]. In the tracheal tube alone group, the trachea was intubated with a tracheal tube alone. The use of a stylet was not permitted in the tracheal tube alone group for first-attempt intubation (Figure S1 in the electronic supplementary material). All the tracheal intubations were performed under general anaesthesia.

Decisions regarding all other aspects of patient care during and after intubation, including the types of laryngoscope blade and tracheal tube, the choice and dosing of hypnotic and neuromuscular blocking agents and bag-mask ventilation between induction and laryngoscopy, were at the discretion of attending physicians according to local expertise and clinical practice. To avoid extremes of practice, general measures during intubation were recommended. Head-up position was recommended. The Montpellier intubation protocol [24] was strongly advised to be followed for each procedure. Briefly, this includes, before intubation was performed: fluid loading in absence of cardiogenic oedema and early introduction of vasopressors, preoxygenation with noninvasive ventilation with or without high-flow nasal cannula oxygen for apnoeic oxygenation in the case of acute respiratory failure, preparation of sedation by the nursing team and the presence of two operators. During the intubation period, recommended induction was rapid sequence induction using short acting hypnotics (etomidate or ketamine or propofol in case of hemodynamic stability), and a rapid onset muscle relaxant (succinylcholine or rocuronium in case of hyperkalaemia), with application of cricoid pressure (Sellick manoeuvre). After the intubation, were performed: verification of the tube’s position by capnography, initiation of long-term sedation as soon as possible (to avoid agitation) and protective ventilation with low insufflated airway pressure [low tidal volume, initially low positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)] and low respiratory rate and a recruitment manoeuvre following intubation after hemodynamic stabilization. At any time, vasopressors were recommended to prevent or limit of severe hemodynamic collapse [24].

The type of blade (plastic or metal, size 3 or 4) for standard laryngoscopy was left to the operator discretion [25]. The availability of equipment for management of a difficult airway was checked. The difficulty of intubation was assessed using the Mallampati score III or IV, obstructive sleep Apnea syndrome, reduced mobility of Cervical spine, limited mouth Opening, Coma, severe Hypoxemia, non-Anaesthesiologist (MACOCHA) score [1]. During the procedure, after preoxygenation, the patient was ventilated in case of desaturation to less than 90%. In case of inadequate ventilation and unsuccessful intubation, emergency non-invasive airway ventilation (supraglottic airway) was used. In cases of intubation failure, the intubation algorithm of each unit was followed.

A trained nurse or physician who was not involved in the performance of the procedure collected data for periprocedural outcomes, including first-attempt intubation success and complications related to tracheal intubation during the interval between induction and 1 h after tracheal intubation. Immediately after each tracheal intubation, the operator reported the subjective difficulty of tracheal intubation, traumatic injuries during the procedure and the level of operator experience. Trial personnel collected data related to baseline characteristics, management before and after laryngoscopy and clinical outcomes from the medical record.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients with first-attempt intubation success [7,8,9]. The prespecified secondary outcome was the proportion of patients who presented at least one of the following complications related to tracheal intubation [1, 24, 26] within the hour following tracheal intubation. Complications were defined as severe hypoxemia (decrease in oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry < 80% during intubation attempts), severe collapse (defined as systolic blood pressure less than 65 mm Hg recorded at least one time or less than 90 mm Hg that lasted 30 min despite 500–1000 ml of fluid loading (crystalloids or colloids solutions) or requiring introduction of vasoactive support), cardiac arrest, death, operator-assessed difficult intubation, oesophageal intubation, operator-reported aspiration, arrhythmia (supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmia with a pulse rhythm that required therapy), agitation [24, 26].

The main safety outcomes were the serious adverse events evaluated by the proportion of patients with traumatic injuries related to the tracheal intubation: mucosal bleeding, laryngeal, tracheal, mediastinal or oesophageal injuries [7, 17] and the lowest peripheral oxygen saturation, highest fraction of inspired oxygen, highest PEEP in the time period of 6–24 h post-intubation [10].

The exploratory clinical outcomes were as follows: severe hypoxemia, severe collapse, cardiac arrest, death, operator-assessed difficult intubation, oesophageal intubation, operator-reported aspiration, arrhythmia, agitation, ICU length of stay, ICU-free days within the first 28-days since intubation, invasive ventilator-free days within the first 28-days since intubation, 28-day mortality and 90-day mortality [10]. Additional details regarding trial outcomes are provided in the electronic supplementary material.

Statistical analysis

Details regarding the determination of the sample size have been reported previously [22]. Assuming a first-attempt intubation success rate during tracheal intubation of 70% in the tracheal tube alone group and 80% in the tracheal tube + stylet group [8], and less than 10% missing data, we determined that the enrolment of 1040 patients would provide a power of 95% at a two-sided alpha level of 0.05 to detect an absolute between-group difference of 10 percentage points in the first-attempt intubation success.

Statistical analysis was performed in a modified to-treat population, including all the randomised patients except patients who withdraw their consent, patients who were excluded post-randomization because they were found not to meet the inclusion criteria or because they improved after randomization and were not intubated.

The baseline features of the overall population and of each group were described. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages and continuous variables as means with standard deviations (SDs).

First-attempt intubation success rate among patients in the two trial groups was compared with the use of the uncorrected Chi square test. Absolute difference and relative risk with 95% confidence interval (CI) were computed. Subgroups derived from categorical variables were displayed as a forest plot [10] (electronic supplementary material). Significance was determined by the p value for the interaction term, with values less than 0.10 considered suggestive of a potential interaction and values less than 0.05 considered to confirm an interaction.

For secondary, safety and exploratory outcomes, absolute differences and relative risks were reported with the use of point estimates and 95% CI. To adjust for multiple testing for the exploratory analyses (22 exploratory outcomes, electronic supplementary material), we reported the false discovery rate [27].

Missing data were presented, considered as missing completely at random (MCAR) and not imputed, as no missing data were reported for the primary outcome.

All analyses were conducted with the use of SAS software, version 9.4, or R, version 4.0.3.

Results

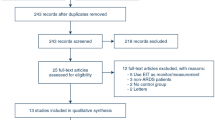

From October 1, 2019, to March 17, 2020, of the 1626 screened patients who met the inclusion criteria, 999 (61.4%) met no exclusion criteria and were enrolled in the modified intention-to-treat analysis (Fig. 1). A total of 501 patients were assigned to receive tracheal tube + stylet, and 498 were assigned to receive tracheal tube alone. There was no protocol deviation (stylet use in the control group or no stylet use in the tracheal tube + stylet group) during the first-attempt intubation. Nearly 50% of patients had acute respiratory failure as an indication for tracheal intubation. Details regarding the trial sites are provided in Table S1 in the electronic supplementary material. Characteristics of the patients at baseline are presented in Table 1 and in Table S2 and Table S3 in the electronic supplementary material. Drugs, characteristics of fluid loading and vasopressors, characteristics of the tracheal intubation and material used for tracheal intubation are presented in Table S4 through Table S8 in the electronic supplementary material.

A total of 392 patients (78.2%) in the tracheal tube + stylet group had first-attempt intubation success, as compared with 356 (71.5%) in the tracheal tube alone group (absolute risk difference, 6.7; 95% CI 1.4–12.1; relative risk, 1.10; 95% CI 1.02–1.18; P = 0.01; Fig. 2). In prespecified subgroup analyses, none of the prespecified characteristics, including indication for tracheal intubation and neuromuscular blocker use, appeared to modify the effect of tracheal tube + stylet on the first-attempt intubation success rate (Fig. 3).

First-attempt intubation success and Complications related to Intubation. The percentages of patients who had the primary outcome, i.e., first-attempt intubation success, and the main secondary outcome, i.e., complications related to intubation are shown in each group. The T bars represent the upper limit of the 95% confidence intervals for the event rate

Subgroup Analyses of the Primary Outcome. Shown is the absolute difference risk in the first-attempt intubation success rate between patients receiving tracheal tube + Stylet and those receiving tracheal tube alone in prespecified subgroups. The horizontal bars represent the 95% confidence intervals around the absolute difference. The number of patients in each group is shown. SAPS Simplified Acute Physiologic Score; BIPAP Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure; MACOCHA Mallampati score III or IV, obstructive sleep Apnea syndrome, reduced mobility of Cervical spine, limited mouth Opening, severe Hypoxemia, Coma, non-Anesthesiologist

The number needed to treat with Stylet to prevent one intubation failure was 14.8 (95% CI 8.3–71.7).

A total of 194 patients (38.7%) in the tracheal tube + stylet group had at least one complication related to tracheal intubation, as compared with 200 patients (40.2%) in the tracheal tube alone group (absolute risk difference, − 1.5; 95%CI − 7.5 to 4.6; relative risk, 0.96; 95% CI 0.83–1.12; P = 0.64) (Table 2, Fig. 2).

The tracheal tube + stylet group and the tracheal tube alone group did not significantly differ regarding the incidence of serious adverse events (4.0% vs. 3.6%; absolute risk difference, 0.4; 95%CI − 2.0 to 2.8; relative risk, 1.10; 95% CI 0.59 to 2.06. P = 0.76) (Table 2). In addition, there was no significant between-group difference in lowest peripheral oxygen saturation, higher PEEP and highest fraction of inspired oxygen in the 24 h after tracheal intubation (Table 2), nor in the separate analysis of each complication, the number of invasive ventilatory-free days and mortality (Table 2). Additional details on outcomes are provided in Table S9 in the electronic supplementary material.

Discussion

In this multicentre, randomised trial, performed in critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation, the use of stylet for tracheal intubation resulted in significantly higher first-attempt intubation success than the use of tracheal tube alone. The results suggest that for every fifteen critically ill patients undergoing tracheal intubation, using tracheal tube + stylet would prevent failure of first-attempt intubation in one patient.

Airway interventions are the procedures most commonly associated with mortality and serious morbidity in the ICU [11]. Physiological disturbances such as hypoxemia and hypotension [11] add to the degree of difficulty, shortening the safe apnea time and cognitively overloading the operator. Added to this, ICU is not designed for airway management in the same way as the operating room is, creating logistical challenges to achieve first-attempt intubation success.

Ten to 15% of patients admitted to the ICU will undergo tracheal intubations [1]. A large number of tracheal intubation are likely to be performed each year worldwide in the ICU [28]. As the most common and severe complication in patients with COVID-19 is acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, the current COVID-19 pandemic has further increased the number of patients requiring tracheal intubation for invasive mechanical ventilation [2].

The stylet presents some advantages for airway management. Its cost is low, it is easily available worldwide and does not require experience of the operator to be used, contrary to other devices like a videolaryngoscope [14]. It has been suggested that the use of a stylet could increase the risk of mucosal bleeding, laryngeal, tracheal, mediastinal or oesophageal injuries [7, 17] during tracheal intubation. However, our trial reported that the rate of traumatic injuries was similar in the two groups (Table 2). Added to its low cost and to its efficacy to increase first-attempt intubation success (Fig. 2) in all subgroups of patients (Fig. 3), the benefit ratio assessment is largely in favour of using a stylet when performing a tracheal intubation. However, subgroup analyses can only generate hypotheses and need to be confirmed by further studies [29]. Moreover, while first-attempt intubation success was higher in the tracheal tube + Stylet group, no difference regarding the main secondary outcome, complications related to intubation, was highlighted between groups. The current trial was not designed to show a difference in this prespecified secondary outcome, which may explain the lack of difference in complications related to intubation.

It is worth noting that a large randomised controlled trial performed in emergency patients compared bougie versus tracheal tube plus stylet [7]. The authors found that use of a bougie compared with an endotracheal tube + stylet resulted in significantly higher first-attempt intubation success. However, the setting differed from our study, as the patients were included in the emergency department and not in the ICUs.

Our trial has certain strengths. The trial design included randomisation to balance baseline confounders and the conduct of the trial at multiple centres to increase generalizability. Operators were not selected according to previous experience. It was a pragmatic trial, designed to set out a simple question, which gives evidence about the efficacy of stylet use under real-world conditions. Moreover, rates of missing data were low, which contributes to a good internal validity of the results.

Our trial has a few limitations. First, the nature of the trial intervention did not allow blinding of the operators. The research staff that collected the data was present at the time of intubation and, therefore, it is difficult to assume that they really achieve a "real masking" of the procedure, even if the research staff tried as much as possible to be blinded of the group of intubation. Since our trial involved only ICU patients, it is unclear whether these results can be generalized to patients undergoing tracheal intubation in the hospital wards, emergency department or in a prehospital setting. Moreover, the full sample size was not reached because a few patients randomized did not complete the trial for reasons detailed in Fig. 1. However, the number of patients who did not complete the trial was similar between groups, as the reasons for not completing the trial. Second, the Macintosh laryngoscope was the device used for the first attempt at laryngoscopy, in line with the ICU airway management recommendations [15, 19,20,21, 30]. Concerns were recently raised in the context of COVID-19 pandemic regarding the risk of transmission to healthcare workers using a Macintosh laryngoscope rather than a videolaryngoscope [3, 31,32,33]. However, to our knowledge, no evidence of increased risk of transmission using a Macintosh laryngoscope in comparison with a videolaryngoscope was demonstrated. Moreover, contrary to the stylet use, there is a risk of increase of complications related to intubation when the videolaryngoscope device is used in the hands of inexperienced operators [8]. Using a stylet is already recommended for use with a videolaryngoscope, especially those with a hyperangulated blade, therefore making these findings potentially relevant even with videolaryngoscope use, though not tested [3]. Third, no difference of first-attempt intubation success was highlighted in the subgroups of patients with predicted difficult intubation or with obesity, probably due to the limited size of these subgroups (40 patients and 200 patients respectively, Fig. 3), resulting in inadequate power to conclude. Similarly, no difference was highlighted according to indication for tracheal intubation suggesting that the stylet can be used both in patients with and without acute respiratory failure. The group without neuromuscular blocker use had a very low sample size to be able to draw any conclusion. Fourth, we did not report and compare the position of the patients, especially the position of the patients' head and neck, which can significantly affect performance of direct laryngoscopy. The starting time of endotracheal intubation after use of relaxants was not described. However, because of the large sample size and the randomised design, we can speculate that these important potential confounding factors are balanced between groups. Fifth, the time taken for tracheal intubation was measured (Table S6) and there was no statistical difference between the two groups. Therefore, the use of a stylet was not associated with reduced time for tracheal intubation, despite a higher first-attempt intubation success rate in the tracheal tube + stylet group.

Conclusions

In this multicentre, randomised trial involving critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation, the use of a stylet for tracheal intubation was safe and resulted in significantly higher first-attempt intubation success than the use of a tracheal tube alone. The results of this study have the potential to change airway management practice in critically ill patients.

Data sharing

Research data and other material (eg, study protocol and statistical analysis plan) will be made available to the scientific community, immediately on publication, with as few restrictions as possible. All requests should be submitted to the corresponding author who will review with the other investigators for consideration. A data use agreement will be required before the release of participant data and institutional review board approval as appropriate.

References

De Jong A, Molinari N, Terzi N, Mongardon N, Arnal JM, Guitton C, Allaouchiche B, Paugam-Burtz C, Constantin JM, Lefrant JY, Leone M, Papazian L, Asehnoune K, Maziers N, Azoulay E, Pradel G, Jung B, Jaber S (2013) Early identification of patients at risk for difficult intubation in the intensive care unit: development and validation of the MACOCHA score in a multicenter cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187:832–839

Cook TM, El-Boghdadly K, McGuire B, McNarry AF, Patel A, Higgs A (2020) Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19: Guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the Association of Anaesthetists the Intensive Care Society, the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia 75:785–799

Patwa A, Shah A, Garg R, Divatia JV, Kundra P, Doctor JR, Shetty SR, Ahmed SM, Das S, Myatra SN (2020) All India difficult airway association (AIDAA) consensus guidelines for airway management in the operating room during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Anaesth 64:S107-s115

De Jong A, Molinari N, Pouzeratte Y, Verzilli D, Chanques G, Jung B, Futier E, Perrigault PF, Colson P, Capdevila X, Jaber S (2015) Difficult intubation in obese patients: incidence, risk factors, and complications in the operating theatre and in intensive care units. Br J Anaesth 114:297–306

Russotto V, Myatra SN, Laffey JG, Tassistro E, Antolini L, Bauer P, Lascarrou JB, Szuldrzynski K, Camporota L, Pelosi P, Sorbello M, Higgs A, Greif R, Putensen C, Agvald-Öhman C, Chalkias A, Bokums K, Brewster D, Rossi E, Fumagalli R, Pesenti A, Foti G, Bellani G (2021) Intubation practices and adverse peri-intubation events in critically ill patients from 29 countries. JAMA 325:1164–1172

De Jong A, Rolle A, Pensier J, Capdevila M, Jaber S (2020) First-attempt success is associated with fewer complications related to intubation in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 46:1278–1280

Driver BE, Prekker ME, Klein LR, Reardon RF, Miner JR, Fagerstrom ET, Cleghorn MR, McGill JW, Cole JB (2018) Effect of use of a Bougie vs endotracheal tube and stylet on first-attempt intubation success among patients with difficult airways undergoing emergency intubation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 319:2179–2189

Lascarrou JB, Boisrame-Helms J, Bailly A, Le Thuaut A, Kamel T, Mercier E, Ricard JD, Lemiale V, Colin G, Mira JP, Meziani F, Messika J, Dequin PF, Boulain T, Azoulay E, Champigneulle B, Reignier J (2017) Video laryngoscopy vs direct laryngoscopy on successful first-pass orotracheal intubation among ICU patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 317:483–493

Guihard B, Chollet-Xémard C, Lakhnati P, Vivien B, Broche C, Savary D, Ricard-Hibon A, Marianne Dit Cassou PJ, Adnet F, Wiel E, Deutsch J, Tissier C, Loeb T, Bounes V, Rousseau E, Jabre P, Huiart L, Ferdynus C, Combes X (2019) Effect of rocuronium vs succinylcholine on endotracheal intubation success rate among patients undergoing out-of-hospital rapid sequence intubation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 322:2303–2312

Casey JD, Janz DR, Russell DW, Vonderhaar DJ, Joffe AM, Dischert KM, Brown RM, Zouk AN, Gulati S, Heideman BE, Lester MG, Toporek AH, Bentov I, Self WH, Rice TW, Semler MW (2019) Bag-mask ventilation during tracheal intubation of critically ill adults. N Engl J Med 380:811–821

De Jong A, Rolle A, Molinari N, Paugam-Burtz C, Constantin JM, Lefrant JY, Asehnoune K, Jung B, Futier E, Chanques G, Azoulay E, Jaber S (2018) Cardiac arrest and mortality related to intubation procedure in critically ill adult patients: a multicenter cohort study. Crit Care Med 46:532–539

Cook NW, Harper J, Benger J (2011) Major complications of airway management in the UK: results of the Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. Part 2: intensive care and emergency departments. B J Anaesth 106:632–642

Russell DW, Casey JD, Gibbs KW, Dargin JM, Vonderhaar DJ, Joffe AM, Ghamande S, Khan A, Dutta S, Landsperger JS, Robison SW, Bentov I, Wozniak JM, Stempek S, White HD, Krol OF, Prekker ME, Driver BE, Brewer JM, Wang L, Lindsell CJ, Self WH, Rice TW, Semler MW, Janz D (2020) Protocol and statistical analysis plan for the PREventing cardiovascular collaPse with Administration of fluid REsuscitation during Induction and Intubation (PREPARE II) randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open 10:e036671

Janz DR, Casey JD, Semler MW, Russell DW, Dargin J, Vonderhaar DJ, Dischert KM, West JR, Stempek S, Wozniak J, Caputo N, Heideman BE, Zouk AN, Gulati S, Stigler WS, Bentov I, Joffe AM, Rice TW (2019) Effect of a fluid bolus on cardiovascular collapse among critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation (PrePARE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 7:1039–1047

Martin M, Decamps P, Seguin A, Garret C, Crosby L, Zambon O, Miailhe AF, Canet E, Reignier J, Lascarrou JB (2020) Nationwide survey on training and device utilization during tracheal intubation in French intensive care units. Ann Intensive Care 10:2

Sorbello M, Hodzovic I (2020) Tracheal tube introducers (Bougies), stylets and airway exchange catheters. In: Kristensen MS, Cook T (eds) Core topics in airway management. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 130–139

Kotoda M, Oguchi T, Mitsui K, Hishiyama S, Ueda K, Kawakami A, Matsukawa T (2019) Removal methods of rigid stylets to minimise adverse force and tracheal tube movement: a mathematical and in-vitro analysis in manikins. Anaesthesia 74:1041–1046

Brodsky MB, Akst LM, Jedlanek E, Pandian V, Blackford B, Price C, Cole G, Mendez-Tellez PA, Hillel AT, Best SR, Levy MJ (2021) Laryngeal injury and upper airway symptoms after endotracheal intubation during surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 132(4):1023–1032

Quintard H, Her E, Pottecher J, Adnet F, Constantin JM, De Jong A, Diemunsch P, Fesseau R, Freynet A, Girault C, Guitton C, Hamonic Y, Maury E, Mekontso-Dessap A, Michel F, Nolent P, Perbet S, Prat G, Roquilly A, Tazarourte K, Terzi N, Thille AW, Alves M, Gayat E, Donetti L (2017) Intubation and extubation of the ICU patient. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 36:327–341

Higgs A, McGrath BA, Goddard C, Rangasami J, Suntharalingam G, Gale R, Cook TM (2018) Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. Br J Anaesth 120:323–352

Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Caplan RA, Blitt CD, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, Benumof JL, Berry FA, Bode RH, Cheney FW, Guidry OF, Ovassapian A (2013) Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology 118:251–270

Jaber S, Rolle A, Jung B, Chanques G, Bertet H, Galeazzi D, Chauveton C, Molinari N, De Jong A (2020) Effect of endotracheal tube plus stylet versus endotracheal tube alone on successful first-attempt tracheal intubation among critically ill patients: the multicentre randomised STYLETO study protocol. BMJ Open 10:e036718

Scott NW, McPherson GC, Ramsay CR, Campbell MK (2002) The method of minimization for allocation to clinical trials. a review. Control Clin Trials 23:662–674

Jaber S, Jung B, Corne P, Sebbane M, Muller L, Chanques G, Verzilli D, Jonquet O, Eledjam J-J, Lefrant J-Y (2010) An intervention to decrease complications related to endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: a prospective, multiple-center study. Intensive Care Med 36:248–255

Langeron O, Bourgain JL, Francon D, Amour J, Baillard C, Bouroche G, Chollet Rivier M, Lenfant F, Plaud B, Schoettker P, Fletcher D, Velly L, Nouette-Gaulain K (2018) Difficult intubation and extubation in adult anaesthesia. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 37:639–651

Jaber S, Amraoui J, Lefrant J-Y, Arich C, Cohendy R, Landreau L, Calvet Y, Capdevila X, Mahamat A, Eledjam J-J (2006) Clinical practice and risk factors for immediate complications of endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: a prospective, multiple-center study. Crit Care Med 34:2355–2361

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc: Ser B (Methodol) 57:289–300

Bauer J, Brüggmann D, Klingelhöfer D, Maier W, Schwettmann L, Weiss DJ, Groneberg DA (2020) Access to intensive care in 14 European countries: a spatial analysis of intensive care need and capacity in the light of COVID-19. Intensive Care Med 46:2026–2034

Assmann SF, Pocock SJ, Enos LE, Kasten LE (2000) Subgroup analysis and other (mis)uses of baseline data in clinical trials. Lancet 355:1064–1069

Myatra SN, Ahmed SM, Kundra P, Garg R, Ramkumar V, Patwa A, Shah A, Raveendra US, Shetty SR, Doctor JR, Pawar DK, Ramesh S, Das S, Divatia JV (2017) Republication: all India Difficult Airway Association 2016 guidelines for tracheal intubation in the intensive care unit. Indian J Crit Care Med 21:146–153

De Jong A, Pardo E, Rolle A, Bodin-Lario S, Pouzeratte Y, Jaber S (2020) Airway management for COVID-19: a move towards universal videolaryngoscope? Lancet Respir Med 8:555

El-Boghdadly K, Wong DJN, Owen R, Neuman MD, Pocock S, Carlisle JB, Johnstone C, Andruszkiewicz P, Baker PA, Biccard BM, Bryson GL, Chan MTV, Cheng MH, Chin KJ, Coburn M, Jonsson Fagerlund M, Myatra SN, Myles PS, O’Sullivan E, Pasin L, Shamim F, van Klei WA, Ahmad I (2020) Risks to healthcare workers following tracheal intubation of patients with COVID-19: a prospective international multicentre cohort study. Anaesthesia 75:1437–1447

De Jong A, Pouzeratte Y, Laplace A, Normanno M, Rollé A, Verzilli D, Perrigault PF, Colson P, Capdevila X, Molinari N, Jaber S (2021) Macintosh videolaryngoscope for intubation in the operating room: a comparative quality improvement project. Anesth Analg 132(2):524–535

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients who participated in our research. We thank the research staff at all the sites for their help conducting the study. We thank the Montpellier University Hospital for funding and its general director, Thomas LE LUDEC, for his support. List of Styleto investigators: Montpellier University Hospital (medico-surgical ICU, trauma ICU)—Samir Jaber, Gérald Chanques, Fouad Belafia, Audrey De Jong, Séverin Ramin, Xavier Capdevila, Jonathan Charbit; Pointe à Pitre University Hospital intensive care unit, Guadeloupe—Amélie Rollé, Michel Carles ; Clermont-Ferrand University Hospital (surgical ICU, medico-surgical ICU, neuro ICU, medical ICU)—Thomas Godet, Matthieu Jabaudon, Emmanuel Futier, Raiko Blondonnet, Bertrand Souweine; Grenoble University Hospital—Nicolas Terzi, Charlotte Cordier, Florian Sigaud; Toulouse University Hospital—Béatrice Riu; Angers University Hospital (surgical ICU, medical ICU)—Pierre Asfar, Sigismond Lasocki; Marseille University Hospital (North Hospital medical ICU, North Hospital surgical ICU, La Timone Hospital medical ICU, La Timone Hospital surgical ICU)—Jeremy Bourenne, Marc Gainnier, Laurent Papazian, Eloi Prudhomme, Djamel Mokart, Marc Léone; Saint-Louis Paris APHP University Hospital—Virginie Lemiale, Elie Azoulay; Dijon University Hospital—Jean-Pierre Quenot, Pascal Andreu, Marie Labruyère, Jean-Baptiste Roudaut, Marine Jacquier ; Le Mans Hospital—Christophe Guitton; La-Pitié Salpetrière Paris APHP University Hospital—Mona Assefi, Elodie Baron, Cyril Quemeneur, Jean-Michel Constantin; Bordeaux University Hospital (medico-surgical ICU of Magellan Center, Haut Levesque surgical ICU)—Matthieu Biais, Hadrien Rozé, Alexandre Ouattara; Nimes University Hospital—Martin Mahul, Laurent Muller, Jean-Yves Lefrant, Claire Roger, Saber Barbar; Tours University Hospital—Martine Ferrandière; Valenciennes Hospital—Fabien Lambiotte, Piehr Saint-Léger; Lyon University Hospital—Thomas Rimmelé, Céline Monard, Paul Abraham; Strasbourg University Hospital—Julien Pottecher, Pierre-Olivier Ludes; Nantes University Hospital—Karim Asehnoune; Saint-Antoine Paris APHP University Hospital—Emmanuel Pardo, Marc Garnier; Lille University Hospital—Matthias Garot, Anne Bignon, Benoit Tavernier; Lariboisière Paris APHP University Hospital—Benjamin Chousterman, Etienne Gayat; Nancy University Hospital—Bruno Levy; Nice University Hospital—Jean Dellamonica

Funding

This trial is an investigator-initiated trial, funded by Montpellier University Hospital, Montpellier 34000, France. The funding source had no role in the conception, design, or conduct of the trial, nor did their representatives participate in the collection, management, analysis, interpretation, or presentation of the data or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors designed the trial, collected the data, and performed the analyses. There was no industry support or involvement in the trial. All the authors revised the manuscript, vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data, and approved the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

SJ, AR, TG, NT, BR, PA, JB, SR, VL, JPQ, CG, EP, CQ, RB, MB, LM, AO, MF, PSL, TR, JP, GC, FB, CC, KA, EF, EA and ADJ wrote the manuscript. HH and NM were the study statisticians. ADJ and SJ obtained the funding. All authors were involved in the data analysis and interpretation. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

SJ reports receiving consulting fees from Drager, Medtronic, Baxter, Fresenius-Xenios, and Fisher & Paykel. TR is a paid consultant of bioMerieux and Baxter. He has received grant support from bioMerieux, Baxter and Fresenius Medical Care and fees for lectures during industry symposia for bioMerieux, Baxter, Fresenius Medical Care, Bbraun and Nikkiso. VL reported being a member of a research group that has received grants from Alexion, Baxter, MSD, Gilead, Sanofi, Celgène. ADJ reports receiving consulting fees from Medtronic. No conflict of interests is reported for other authors.

Ethical approval

The trial was approved for all centers by a central Ethics Committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Nord-Ouest, France, 2019-A01180-57) according to French law. An informed consent was required. The STYLETO trial was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov with trial identification number NCT04079387 before the first inclusion in the trial.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A full list of the STYLETO investigators is provided in the Acknowledgement Section.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaber, S., Rollé, A., Godet, T. et al. Effect of the use of an endotracheal tube and stylet versus an endotracheal tube alone on first-attempt intubation success: a multicentre, randomised clinical trial in 999 patients. Intensive Care Med 47, 653–664 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-021-06417-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-021-06417-y