Abstract

Purpose

Mental health trajectories during the COVID-19 pandemic have been examined in Veterans with tenuous social connections, i.e., those with recent homelessness (RHV) or a psychotic disorder (PSY), and in control Veterans (CTL). We test potential moderating effects on these trajectories by psychological factors that may help individuals weather the socio-emotional challenges associated with the pandemic (i.e., ‘psychological strengths’).

Methods

We assessed 81 PSY, 76 RHV, and 74 CTL over 5 periods between 05/2020 and 07/2021. Mental health outcomes (i.e., symptoms of depression, anxiety, contamination concerns, loneliness) were assessed at each period, and psychological strengths (i.e., a composite score based on tolerance of uncertainty, performance beliefs, coping style, resilience, perceived stress) were assessed at the initial assessment. Generalized models tested fixed and time-varying effects of a composite psychological strengths score on clinical trajectories across samples and within each group.

Results

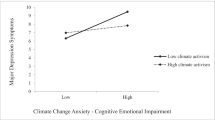

Psychological strengths had a significant effect on trajectories for each outcome (ps < 0.05), serving to ameliorate changes in mental health symptoms. The timing of this effect varied across outcomes, with early effects for depression and anxiety, later effects for loneliness, and sustained effects for contamination concerns. A significant time-varying effect of psychological strengths on depressive symptoms was evident in RHV and CTL, anxious symptoms in RHV, contamination concerns in PSY and CTL, and loneliness in CTL (ps < 0.05).

Conclusion

Across vulnerable and non-vulnerable Veterans, presence of psychological strengths buffered against exacerbations in clinical symptoms. The timing of the effect varied across outcomes and by group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Deidentified data are available upon request.

References

Green MF, Wynn JK, Gabrielian S, Hellemann G, Horan WP, Kern RS, Lee J, Marder SR, Sugar CA (2020) Motivational and cognitive factors linked to community integration in homeless veterans: study 1 - individuals with psychotic disorders. Psychol Med 52(1):169–177. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720001889

Tsai J, Mares AS, Rosenheck RA (2012) Does housing chronically homeless adults lead to social integration? Psychiatr Serv 63(5):427–434

Tsai J, Rosenheck RA (2015) Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev 37(1):177–195

Wynn JK, McCleery A, Novacek D, Reavis EA, Tsai J, Green MF (2021) Clinical and functional effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing on vulnerable veterans with psychosis or recent homelessness. J Psychiatr Res 138:42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.051

Wynn JK, McCleery A, Novacek DM, Reavis EA, Senturk D, Sugar CA, Tsai J, Green MF (2022) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and functional outcomes in Veterans with psychosis or recent homelessness: a 15-month longitudinal study. PLOS One 17(8):e0273579. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273579

Kato T (2015) Frequently used coping scales: a meta-analysis. Stress Health 31(4):315–323. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2557

Cristóbal-Narváez P, Haro JM, Koyanagi A (2020) Perceived stress and depression in 45 low- and middle-income countries. J Affect Disord 274:799–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.04.020

Carleton RN (2016) Into the unknown: a review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. J Anxiety Disord 39:30–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.02.007

Shihata S, McEvoy PM, Mullan BA, Carleton RN (2016) Intolerance of uncertainty in emotional disorders: what uncertainties remain? J Anxiety Disord 41:115–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.05.001

Campellone TR, Sanchez AH, Kring AM (2016) Defeatist performance beliefs, negative symptoms, and functional outcome in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Schizophr Bull 42(6):1343–1352. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbw026

Grant PM, Beck AT (2009) Defeatist beliefs as a mediator of cognitive impairment, negative symptoms, and functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 35(4):798–806. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbn008

Green MF, Hellemann G, Horan WP, Lee J, Wynn JK (2012) From perception to functional outcome in schizophrenia: modeling the role of ability and motivation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69(12):1216–1224. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.652

Wood SN (2011) Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Statistical Methodology) 73(1):3–36

Team RC, R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2021: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

Olatunji BO, Williams BJ, Haslam N, Abramowitz JS, Tolin DF (2008) The latent structure of obsessive-compulsive symptoms: a taxometric study. Depress Anxiety 25(11):956–968. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20387

Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Gloster AT, Lieb R (2012) Obsessive–compulsive disorder in the community: 12-month prevalence, comorbidity and impairment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47(3):339–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0337-5

Kim MK, Lee KS, Kim B, Choi TK, Lee SH (2016) Impact of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on intolerance of uncertainty in patients with panic disorder. Psychiatry Investig 13(2):196–202. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2016.13.2.196

Ladouceur R, Dugas MJ, Freeston MH, Léger E, Gagnon F, Thibodeau N (2000) Efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: evaluation in a controlled clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 68(6):957–964

Granholm E, Holden J, Link PC, McQuaid JR, Jeste DV (2013) Randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral social skills training for older consumers with schizophrenia: defeatist performance attitudes and functional outcome. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 21(3):251–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2012.10.014

Granholm E, Holden J, Worley M (2018) Improvement in negative symptoms and functioning in cognitive-behavioral social skills training for schizophrenia: mediation by defeatist performance attitudes and asocial beliefs. Schizophr Bull 44(3):653–661. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx099

Stächele T, Domes G, Wekenborg M, Penz M, Kirschbaum C, Heinrichs M (2020) Effects of a 6-week internet-based stress management program on perceived stress, subjective coping skills, and sleep quality. Front Psych 11:463

Antoni MH, Ironson G, Schneiderman N (2007) Cognitive-behavioral stress management. Oxford University Press

Pietrzak RH, Tsai J, Southwick SM (2021) Association of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder with posttraumatic psychological growth among US veterans during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 4(4):e214972–e214972. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4972

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001) The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16(9):606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166(10):1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Abramowitz JS, Deacon BJ, Olatunji BO, Wheaton MG, Berman NC, Losardo D, Timpano KR, McGrath PB, Riemann BC, Adams T, Björgvinsson T, Storch EA, Hale LR (2010) Assessment of obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions: development and evaluation of the dimensional obsessive-compulsive scale. Psychol Assess 22(1):180–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018260

Russell D, Peplau LA, Ferguson ML (1978) Developing a measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess 42(3):290–294. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11

Freeston MH, Rhéaume J, Letarte H, Dugas MJ, Ladouceur R (1994) Why do people worry? Personality Individ Differ 17(6):791–802

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983) A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 24(4):385–396

Weissman AN, Beck AT (1978) Development and validation of the dysfunctional attitude scale: a preliminary investigation. In: Proceedings of the meeting of the American Educational Research Association. Toronto, ON

Carver CS (1997) You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med 4(1):92–100. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to our recruiters and interviewers without whom this work would not have been possible: Lauren Catalano, PhD, Gerard De Vera, Arpi Hasratian, Julio Iglesias, Brian Ilagan, Mark McGee, Jessica McGovern, PhD, Ana Ceci Myers, Megan Olsen, and Michelle Torreliza. Finally, we thank our Veteran volunteers for taking the time to participate in this research. This study was funded by the Research Enhancement Award Program to Enhance Community Integration in Homeless Veterans (MFG) Rehabilitation Research and Development grant D1875-F from the Department of Veteran Affairs, https://www.research.va.gov/, and by the VA National Center on Homelessness among Veterans (MFG), https://www.va.gov/homeless/nchav/index.asp. Amanda McCleery, PhD, is supported by a career development award from National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH108829). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM, JKW, CS, JT, EAR, and MFG: contributed to the conception of the study and the research design. AM, JKW, and DMN: contributed to data acquisition and project management. AM, JKW, EAR, DS, CS, and MFG: contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data. AM: wrote the main manuscript text, and JKW: prepared the figures. All authors contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

McCleery, A., Wynn, J.K., Novacek, D.M. et al. The impact of psychological strengths on Veteran populations’ mental health trajectories during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 59, 111–120 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02518-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02518-9