Abstract

Background

The increased prevalence of overweight in Canadian children has stimulated interest in their lifestyle behaviours. The purpose of this research was to investigate dietary intake and food behaviours of Ontario students in grades six, seven, and eight.

Methods

Males and females from grades six to eight were recruited from a stratified random selection of schools from Ontario. Data were collected using the web-based “Food Behaviour Questionnaire”, which included a 24-hour diet recall and food frequency questionnaire. Nutrients were analyzed using ESHA Food Processor and the 2001 Canadian Nutrient File database. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated based on self-reported weight and height, and classified according to the Centers for Disease Control BMI for age percentiles.

Results

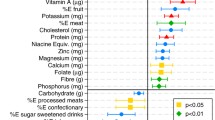

The sample included males (n=315) and females (n=346) in grades 6, 7, and 8 from 15 schools in Ontario. According to Canada’s Food Guide to Healthy Eating (CFGHE), median intakes were below recommendations for all participants, with the exception of meat and alternatives. Participants consumed a median of 54%, 15%, 31%, 11%, and 8% of total energy from carbohydrates, protein, total fat, saturated fat, and added sugars, respectively. Participants consumed 25% of total energy from foods from the “other” food group (CFGHE). Males had higher intakes of energy, carbohydrates, fat, saturated fat, monounsaturated fat, protein, thiamine, niacin, iron, and zinc than females (all p<0.05), and consumed more grain products servings (p<0.05).

Conclusion

The high consumption of “other” foods, at the expense of nutrient-dense food groups, may ultimately be contributing to the increased weights in childhood and adolescence.

Résumé

Contexte

La prévalence accrue du surpoids chez les enfants canadiens ravive l’intérêt pour les comportements liés au mode de vie des enfants. Notre étude portait sur les apports et les comportements alimentaires d’élèves ontariens de 6e, 7e et 8e année.

Méthode

Nous avons recruté des garçons et des filles de la 6e à la 8e année à partir d’un échantillon aléatoire stratifié d’écoles de l’Ontario. Les données ont été recueillies à l’aide d’un questionnaire en ligne sur les comportements alimentaires, incluant une feuille de rappel des aliments ingérés pendant les 24 dernières heures et un questionnaire sur la fréquence de consommation des produits alimentaires. Les nutriments ont été analysés avec le logiciel Food Processor d’ESHA Research et la version 2001 du Fichier canadien sur les éléments nutritifs. L’indice de masse corporelle (IMC) a été calculé d’après le poids et la taille déclarés par les répondants, puis classé selon les centiles d’IMC selon l’âge publiés par les Centres américains de contrôle des maladies.

Résultats

L’échantillon comportait des garçons (n=315) et des filles (n=346) des classes de 6e, 7e et 8e année de 15 écoles de l’Ontario. Selon le Guide alimentaire canadien pour manger sainement (GACMS), les apports médians étaient inférieurs aux recommandations chez tous les participants, sauf les apports en viandes et substituts. Les participants consommaient en moyenne 54 %, 15 %, 31 %, 11 % et 8 % de leur apport énergétique total sous forme de glucides, de protéines, de matières grasses en général, de graisses saturées et de sucres ajoutés, respectivement. Le quart (25 %) de l’apport énergétique alimentaire total provenait du groupe « autres aliments » (GACMS). Les garçons avaient des apports plus élevés en calories, en glucides, en matières grasses, en graisses saturées, en graisses monoinsaturées, en protéines, en thiamine, en niacine, en fer et en zinc que les filles (p<0,05 dans tous les cas), et ils consommaient plus de portions de produits céréaliers (p<0,05).

Conclusion

La consommation élevée des « autres aliments » aux dépens des groupes riches en éléments nutritifs pourrait en bout de ligne contribuer aux gains de poids observés durant l’enfance et l’adolescence.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Hirsh J. Obesity. N Engl J Med 1997;337(6):396–407.

Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Boyce WF, Vereecken C, Mulvihill C, Roberts C, et al. Comparison of overweight and obesity prevalence in school-aged youth from 34 countries and their relationships with physical activity and dietary patterns. Obes Rev 2005;6(2):123–32.

Tjepkema M. Adult obesity in Canada: Measured height and weight (Statistics Canada). Available online at: https://doi.org/www.statcan.ca/english/research/ 82-620-MIE/2005001/pdf/aobesity.pdf (Accessed December 2006).

Shields M. Overweight Canadian children and adolescents (Statistics Canada). Available online at: https://doi.org/www.statcan.ca/english/research/ 82-620-MIE/2005001/pdf/cobesity.pdf (Accessed December 2006).

Nicklas TA, Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Berenson G. Eating patterns, dietary quality, and obesity. J Am Coll Nutr 2001;20(6):599–608.

Freedman DS, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson, GS. The relation of overweight to cardiovascular risk factors among children and adolescents: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics 1999;103:1175–82.

Ball GD, McCargar, LJ. Childhood obesity in Canada: A review of prevalence estimates and risk factors for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Can J Appl Physiol 2003;28(1):117–40.

Fagot-Campagna A, Pettitt DJ, Engelgau MM, Burrows NR, Geiss LS, Valdez R, et al. Type 2 diabetes among North American children and adolescents: An epidemiology review and a public health perspective. J Pediatr 2000;136(5):664–72.

Wiegand S, Maikowski U, Blankenstein O, Biebermann H, Tarnow P, Gruters A. Type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in European children and adolescents with obesity - A problem that is no longer restricted to minority groups. Eur J Endocrinol 2004;151(2):199–206.

Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute (CFLRI): 2002 Physical Activity Monitor. Available online at: https://doi.org/www.cflri.ca/cflri/ pa/surveys/2002survey/2002survey.html#kids (Accessed August 2004).

Bar-Or O, Foreyt J, Bouchard C, Brownell KD, Dietz WH, Ravussin E, et al. Physical activity, genetic, and nutritional considerations in childhood weight management. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998;30:2–10.

Lowry R, Wechsler H, Galuska DA, Fulton JE, Kann L. Television viewing and its associations with overweight, sedentary lifestyle, and insufficient consumption of fruits and vegetables among US high school students: Differences by race, ethnicity, and gender. J Sch Health 2002;72(10):413–21.

Cohen B, Evers S, Manske S, Bercovitz K, Edward, HG. Smoking, physical activity and breakfast consumption among secondary school students in a Southwestern Ontario community. Can J Public Health 2003;94(1):41–44.

Phillips S, Jacobs-Starkey L, Gray-Donald K. Food habits of Canadians: Food sources of nutrients for the adolescent sample. Can J Diet Pract Res 2004;65(2):81–84.

Garriguet D. Overview of Canadians’ Eating Habits 2004 (Statistics Canada). 2006. Available online at: https://doi.org/www.statcan.ca/english/research/ 82-620-MIE/82-620-MIE2006002.pdf (Accessed December 2006).

Briefel RR, Johnson, CL. Secular trends in dietary intake in the United States. Annu Rev Nutr 2004;24:401–31.

Gibson EL, Wardle J, Watts, CJ. Fruit and vegetable consumption, nutritional knowledge and beliefs in mothers and children. Appetite 1998;31(2):205–28.

Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker, SL. Relation between consumption of sugarsweetened drinks and childhood obesity: A prospective, observational analysis. Lancet 2001;357(9255):505–8.

Troiano RP, Briefel RR, Carroll MD, Bialostosky K. Energy and fat intakes of children and adolescents in the United States: Data from the national health and nutrition examination surveys. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72(5 suppl):1343s-53s.

Hanning RM, Jessup L, Lambraki I, MacDonald C, McCargar L. A web-based approach to assessment of food intake and behaviour of school children and adolescents [Abstract]. Can J Diet Pract Res 2003;64(2);s110.

Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada. Canada’s Food Guide to Healthy Eating. Cat No H39-252/1992E. ISBN 0-662-19648-1.

Canadian Nutrient File 2001b. Health Canada. Available online at: https://doi.org/www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fooda liment/ns-sc/nr-rn/surveillance/cnf-fcen/e_index.html (Accessed August 2004).

Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data 2000;314(4):1–27.

ESHA Research. The Food Processor, Nutrition Analysis and Fitness Software (Version 7.9) [Computer software]. 1987–2002: Salem, OR.

The Canadian nutrient data system. Health Canada. Available online at: https://doi.org/www.hcsc.gc.ca/fn-an/nutrition/fiche-nutri-data/ cnds_vision_scdn_e.html (Accessed February 2006).

Millns H, Woodward M, Bolton-Smith C. Is it necessary to transform nutrient variables prior to statistical analysis? Am J Epidemiol 1995;141(3):251–62.

Horton NJ, Lipsitz, SR. Review of software to fit generalized estimating equation regression models. The American Statistician 1999;53:160–69.

SAS Institute Inc. SAS Statistical Software Package (Version 9) [Computer software]. Cary, NC.

Tremblay MS, Willms, JD. Secular trends in the body mass index of Canadian children. CMAJ 2000;163(11):1429–33.

Carter LM, Whiting SJ, Drinkwater DT, Zello GA, Faulkner RA, Bailey, DA. Self-reported calcium intake and bone mineral content in children and adolescents. J Am Coll Nutr 2001;20(5):502–9.

Veugelers PJ, Fitzgerald AL, Johnston E. Dietary intake and risk factors for poor diet quality among children in Nova Scotia. Can J Public Health 2005;96(3):212–16.

Bandini LG, Must A, Cyr H, Anderson SE, Spadano JL, Dietz, WH. Longitudinal changes in the accuracy of reported energy intake in girls 10–15 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78(3):480–84.

Johansson L, Solvoll K, Bjorneboe GE, Drevon CA. Under- and overreporting of energy intake related to weight status and lifestyle in a nationwide sample. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;68(2):266–74.

Champagne CM, Baker NB, DeLany JP, Harsha DW, Bray, GA. Assessment of energy intake underreporting by doubly labeled water and observations on reported nutrient intakes in children. J Am Diet Assoc 1998;98(4):426–33.

Johnson-Down L, O’Loughlin J, Koski K, Gray- Donald K. High prevalence of obesity in low income and multiethnic schoolchildren: A diet and physical activity assessment. J Nutr 1997;187(12):2310–15.

Lissner L. Measuring food intake in studies of obesity. Public Health Nutr 2002;5(6A):889–92.

Gibson, RS. Principles of Nutrition Assessment, 2nd Ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Bowman, SA. Diets of individuals based on energy intakes from added sugars. Family Eco Nutr Rev 1999;12(2):31–38.

Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Dietary reference intakes: Energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids (Prepublication copy, unedited proofs). Washington, DC, 2002.

Epstein LH, Gordy CC, Raynor HA, Beddome M, Kilanowski CK, Paluch R. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat and sugar intake in families at risk for childhood obesity. Obes Res 2001;9(3):171–78.

Position Statement by the Canadian Diabetes Association. Guidelines for the nutritional management of diabetes mellitus in the new millenium. Can J Diabetes Care 1999;23(3):56–69.

Taylor JP, Evers S, McKenna M. Determinants of healthy eating in children and youth. Can J Public Health 2005;96(Suppl. 3):S20–S26.

Ontario Society of Nutrition Professionals in Public Health School Nutrition Workgroup Steering Committee. Call to action: Creating a healthy school nutrition environment. 2004; March. Available online at: https://doi.org/www.osnpph.on.ca/pdfs/call_to_action.pdf (Accessed December 2006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hanning, R.M., Woodruff, S.J., Lambraki, I. et al. Nutrient Intakes and Food Consumption Patterns Among Ontario Students in Grades Six, Seven, and Eight. Can J Public Health 98, 12–16 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405377

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405377