Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is thought to develop as a result of chronic exposure to cigarette smoke, occupational or other environmental hazards, and it comprises both airways and parenchyma. Acute infections or chronic colonization of airways with bacteria may also contribute to development and/or progression of COPD lung disease. Airway epithelium is the primary target for the inhaled environmental factors and pathogens. The repetitive injury as a result of chronic exposure to environmental factors may result in persistent activation of pathways involved in airway epithelial repair, such as epithelial to mesenchymal transition, altered migration and proliferation of progenitor cells, and abnormal redifferentiation leading to airway remodeling. Development of model systems that mimic chronic airways disease as observed in COPD is required to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the abnormal airway epithelial repair that are specific to COPD, and to also develop novel therapies focused on airway epithelial repair.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a multifactorial disease and is primarily characterized by airflow limitation that is progressive and often not reversible. Structural and functional changes in both airway and alveolar epithelium contribute to airflow limitation. Cigarette smoke, one of the major risk factors for development of COPD, induces structural and functional changes in airway epithelium in vitro and in vivo [1•, 2••, 3, 4••, 5]. Airway epithelium that lines the respiratory tract protects the lungs from external environmental insults, and therefore alteration in structure and function can have a profound impact on host defense against invading pathogens and particulates, and also repair process following an injury. Mounting evidence in recent years has suggested that airway epithelium is indeed both a site of disease initiation and a driver of disease progression [6, 7]. This is due to the understanding of various mechanisms by which epithelium maintains homeostasis after injury and how repeated injury leads to disproportionate activation of repair signals promoting airway disease.

Altered structure and function of airway epithelium in COPD

Epithelium lining the trachea and bronchi (proximal airways) is pseudostratified and is made up of three major cell types: ciliated cells, non-ciliated secretory cells, and basal cells. As the bronchi branches into bronchioles and to terminal bronchioles, the epithelium gradually changes from pseudostratified to simple cuboidal epithelium, and the number of ciliated, goblet, and basal cells gradually decline and non-ciliated cells called Clara cells becomes the major cell type [8]. In the proximal airway and cartilaginous bronchioles, the invagination of epithelium forms submucosal glands, which are characterized by a variable proportion of ciliated cells, goblet cells, and serous cells. Other minor cell types that are present in conducting airways are: 1.) chemosensory or brush cells that contain apical tufts of microvilli and are thought to play a role in regulation of both airway surface fluid secretion and breathing [9, 10]; and 2.) pulmonary neuroendocrine cells, which are typically tall and pyramidal in shape and extend from the basal lamina of the epithelium and possess microvilli [11, 12].

Ciliated cells and secretory cells are the major cell types that contribute to mucociliary clearance function of airway epithelium. Mucociliary clearance depends on the cilia and composition of the airway surface liquid (ASL) lining the airway surface. ASL is made up of two layers, an upper viscoelastic layer of mucins secreted by the goblet cells and submucosal glands, and a lower periciliary layer containing large membrane-bound glyocproteins, as well as tethered mucins (muc-1, muc-4 and muc-16) [13, 14]. The periciliary layer is relatively less viscous, and acts as a lubricating layer for cilia to beat. Hydration of ASL is regulated by the coordinated activity of Chloride secretion (Cl-) and Sodium (Na+) absorption channels. The combination of Cl- secretion and reduced reabsorption of Na+ favors normal ASL hydration and efficient mucociliary clearance. In normal airways, the coordinated functioning of ATP-activated cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), calcium-activated Cl- channel (CaCC), outwardly rectifying Cl- channel (ORCC), Cl- channel 2 (CLC2), and epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) regulate ASL hydration [15]. CFTR negatively regulates ENac, and therefore absent or dsyfunctional CFTR increases ENaC activity leading to hyperabsorption of Na+, an increased driving force for fluid reabsorption resulting in reduced ASL depth and impaired mucociliary clearance, as observed in the chronic airway disease, cystic fibrosis [15]. In addition, aquaporins that regulate transcellular water transport may also a play a role in mucociliary clearance. Aquaporin 3 and 4 are expressed in the basolateral plasmamembrane and their role in hydration of mucus is not established. In contrast, acquaporin 5 is expressed in submucosal glands and has been shown to regulate mucus secretion and hydration [16]. In COPD patients, the impaired mucociliary function may be due to a combination of excessive mucus production, increased viscosity of mucus due to acquired dysfunction of CFTR, reduced acquaporin 5 expression and reduced ciliary beating. Reduced CFTR function has been demonstrated in healthy smokers and in COPD patients and treatment with ivacaftor (a CFTR potentiator) modulated CFTR activity and increased ASL depth in differentiated COPD cells in vitro [17•]. Increased mucus secretion due to mucous metaplasia and hyperplasia has been reported in COPD patients [18]. In addition, Wang et al. showed that increased mucus secretion in COPD patients correlated with reduced expression of acquaporin 5 and cigarette smoke decreased the expression of aquaporin 5 [16]. Furthermore, airway epithelial cells isolated from COPD patients retain the phenotype of goblet cell hyperplasia and show increased mucus secretion in vitro [19], suggesting that airway epithelial cells may acquire epigenetic changes that could contribute negatively to the repair process in COPD patients. Additionally, it has been shown that respiratory epithelial cells exposed to cigarette smoke extract or condensate showed shorter and 70 % fewer cilia compared to control cells [20]. Although mice exposed to cigarette smoke showed slight increases in ciliary beat frequencies at 6 weeks and 3 months, it was significantly reduced at 6 months, and post-mortem examination revealed significant loss of tracheal ciliated cells [21]. Recently, Yaghi et al. provided direct evidence of suppressed ciliary beating in nasal epithelium from COPD patients [22•]. Such changes in the number and function of cilia combined with excessive mucus production and increased viscosity of mucus can significantly impair the mucociliary clearance function of airway epithelium.

Abnormally repaired or remodeled epithelium may also affect the composition of ASL, due to dysregulated activity of secretory cells. ASL contains potent antibacterial peptides and proteins, such as β-defensin, cathelicidin, lactoferrin, secretory IgA, and glycosaminoglycans. Surfactant proteins A, B and D that are present in ASL have also been shown to participate in bacterial clearance by professional phagocytes. Recently, LL-37, which belongs to the cathelicidin family was found to be decreased in COPD patients with advanced lung disease (gold III – IV) [23]. Decreased levels of β-defensin were noted in central airways, but not in distal airways, of COPD patients [24]. Degradation of antimicrobial peptides was also observed in COPD patients after experimental infection with rhinovirus, but not in similarly infected normal subjects [25]. Surfactant protein D, which promotes uptake of bacteria by macrophages, was shown to be reduced in COPD patients [26]. Airway epithelial cells also generate oxidants such as nitric oxide (NO) and hydrogen peroxide, both of which have been shown to play a role in pathogen clearance. Defective NO generation by airway epithelial cells due to reduced nitric oxide synthase (NOS)2 is thought to be responsible for increased viral replication in cystic fibrosis, and overexpression of NOS2 provides protection against viral infection [27, 28]. Hydrogen peroxide generated by dual oxidase, a member of NADPH oxidase in combination with thiocyanate and lactoperoxidase generates the microbicidal oxidant hypothiocyanite, which effectively kills both gram positive and gram negative bacteria, and this innate defense mechanism is defective in cystic fibrosis airway epithelium due to impaired transport of thiocyanate [29]. We showed that COPD airway epithelial cells show a trend in decreased expression of NOS2 and Duox oxidases and this was associated with impaired clearance of rhinovirus [19]. In addition to these defenses, airway epithelial cells also express chemokines and cytokines in response to infection or other environmental stimulus. If this response is not tightly regulated, it could lead to impaired clearance of pathogens and excessive lung inflammation. COPD airway epithelial cells show heightened chemokine responses to rhinovirus infection [19], and COPD patients experimentally infected with rhinovirus showed increased chemokines and more lower respiratory symptoms compared to healthy smokers [30], indicating that dysregulated cytokine responses to viral infection may partly be due to remodeled airway epithelium in COPD.

The barrier function of airway epithelium is regulated by the apical junctional complex, which includes both tight and adherence junctions. Adherence junctions mediate cell-to-cell contact and promote formation of tight junctions, which in turn regulate transportation of solutes and ions across epithelia [31, 32]. Under homeostasis, these intercellular apical junctional complexes prevent inhaled pathogens and other environmental insults from injuring the airways, and also serve as signaling platforms that regulate gene expression, cell proliferation, and differentiation [33, 34]. Therefore sustained insults that affect junctional complexes will disrupt not only barrier function, but may also interfere with normal repair and differentiation of airway epithelium. Airway epithelium is leaky, hyperproliferative, and abnormally differentiated in smokers and in patients with COPD compared to airway epithelium in healthy subjects, due to decreased expression of genes that encode proteins which regulate formation of the apical junctional complex [1•, 35–38]. Infection with viruses or bacteria can also cause transient disruption of tight or adherence junctions [39–41] and the sustained host innate immune responses may further prolong barrier dysfunction. For instance, host factors, such as interferons and TNF-α expressed in response to infection may prolong tight junction disruption long after infection is cleared, enabling the passage of inhaled allergens and pollutants [42, 43]. Interestingly, our on-going studies show that COPD cells show more prolonged (up to 14 days post-infection) interferons and IL-8 responses, and this is associated with barrier dysfunction and mucus hyperplasia and increased mucus production (Ganesan and Sajjan, unpublished results). Bacterial infection is also a frequent cause of COPD exacerbations and these bacteria release virulence factors that can potentially injure and also impede repair of airway epithelium. Incomplete restoration or barrier function of airway epithelium following injury combined with dysregulated antimicrobial defenses and defective mucociliary clearance may increase the risk for recurrence of infections in COPD.

At least three distinct progenitor/stem cells responsible for maintenance of the airway epithelium have been identified in tracheobronchial epithelium. These include Clara cell secretory protein (CCSP)-expressing (CE) cells, a rare population of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)-expressing cells, and basal cells [44–46]. Of these bronchiolar airway progenitor pools, CE cells represent a multipotent progenitor population and CGRP-expressing progenitor cells serve as tissue specific progenitor cells [45, 47, 48]. The significant contribution of basal cells in the regeneration of bronchial epithelium in vivo was highlighted in studies, in which isolated basal cell population was demonstrated to have the capacity for multipotent differentiation [49, 50]. Later, Hong et al. showed that basal cells are multipotent progenitor cells of bronchial airway epithelium and these cells function in concert with non-ciliated Clara cells [44, 51]. Abnormality in number and function of these progenitor/stem cells may significantly affect the repair of the injured airway epithelium. For instance, in patients with chronic lung disease experiencing repetitive injury, limited reservoir of stem/progenitor cells combined with diminished regenerative capacity and/or impaired migration could lead to abnormal wound healing.

Airway epithelial injury and repair

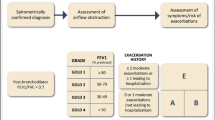

Irrespective of source of the injury, a common sequence for epithelial regeneration following injury has been described, based on in vivo and in vitro studies. Although the precise mechanisms by which the epithelium regenerates by itself are controversial, it can be loosely divided into four steps: dedifferentiation, migration, proliferation and redifferentiation (Fig. 1). In an in vivo study, following mechanical injury (800 μM wide wound) to guinea pig tracheal epithelium, ciliated and secretory cells (possibly basal cells) near the edge of wound were found to dedifferentiate, flatten and migrate over the denuded area within 15 minutes of injury [52]. This was followed by coverage of the wounded site by a tight layer of undifferentiated flattened cells to serve as a temporary patch and provide efficient barrier. After complete migration, which is approximately 30 hours after the injury, mitotic cells were observed, an indication of cell proliferation in the wounded area. Five days after the injury, the wounded area showed fully redifferentiated airway epithelium, suggesting that airway epithelium has the ability to regenerate very quickly post-injury. Other in vivo models for studying regeneration of airway epithelium involved subcutaneous transplantation of denuded human bronchi or denuded rat trachea co-transplanted with human bronchial cells into SCID mice [53, 54]. These studies identified a profile of integrins that are expressed during wound repair, and also demonstrated that repairing or regenerating epithelium is more susceptible than fully differentiated epithelium to transfection with viral vectors [55, 56]. Additionally, the repaired airway epithelium showed integrins and the ratio of ciliated to goblet cells comparable to normal uninjured airway epithelium [53]. These early studies suggest that the regeneration of epithelium is a dynamic process and alteration or interruption at any given step of dedifferentiation, migration, proliferation or redifferentiation due to an abnormal response of epithelial or other cell types, such as fibroblasts and inflammatory cells, may affect the normal repair and regeneration of airway epithelium.

Under normal conditions, acute injury induces EMT in adjacent cells of injured area, which then migrate and cover the injured area to provide temporary patch. In the second step of repair, basal cells migrate to and proliferate in the injured area. In the third step of repair, the proliferated basal cells polarize and undergo redifferentiation to form intact airway epithelium with normal structure and function. C Ciliated cells; Cl Clara cells; G goblet cells; B basal cells; M mesenchymal cells

Molecular mechanisms involved in normal and dysregulated airway epithelial repair and regeneration

-

1.

Epithelial to mesenchymal transition: Normal repair and regeneration of airway epithelium involves numerous closely interacting cells and molecules. Following injury, the first step is dedifferentiation of epithelial cells to form flattened cells, a process which is called epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT). During this step, cell polarity and cell-to-cell contact of epithelial cells are lost and cell-matrix adhesion contacts are remodeled. In addition, markers of epithelial cells such as cytokeratins and E-cadherin are lost and markers of mesenchymal cells or myofibroblasts such as vimentin, N-cadherin, S100A4 and matrix metallo protease (MMP)-9, and alpha smooth muscle actin are acquired [57, 58]. The epithelial cells transdifferentiated into mesenchymal cells are motile and play a key role in both degradation and de novo synthesis of the extracellular matrix, which is essential for migration of cells along the basement membrane. By the secretion of ECM components such as fibronectin and collagen IV, epithelial cells are able to self-regulate their rate of migration. Further fibronectin also acts as a regulator of directional migration of bronchial epithelial cells [59]. As the cells migrate, MMP-9 and/or stromelysin 1 and 3 (MMP-3 and MMP-11 respectively) secreted by transdifferentiated cells or basal cells degrade focal adhesion at the rear of the cell [58, 60, 61]. In bronchial epithelial cells, inactivation of MMP-9 was shown to decrease the migration of cells [62]. MMP-7, which is expressed by uninjured airway epithelial cells has also been shown to play a role in the migration of cells after injury as marked inhibition of tracheal reepithelialization was observed in MMP-7 knockout mice [63]. Depending on the size of the wound, the migration phase lasts about 8 to 15 hours, after which the wound is covered with a layer of flattened undifferentiated cells [52]. These observations suggest that EMT is an important biological process that is required for normal epithelial repair following injury. However, dysregulated EMT may lead to chronic diseases, such as fibrosis, metastasis and cancer progression [64, 65]. In asthma, airway remodeling is also thought to be due to persistent activation of EMT as a result of chronic mucosal injury [66, 67], but there is no data demonstrating loss of adhesion proteins or colocalization of mesenchymal markers within asthmatic airway tissue. In COPD patients, however, there is direct evidence suggesting persistent activation of EMT in airway epithelium. Using bronchial biopsies or explant lung tissue, it was demonstrated that compared to non-smokers, healthy smokers and COPD patients showed decreased expression of epithelial markers such as zona occludence (ZO-)-1, E-cadherin and cytokeratins, and increased expression of markers of mesenchymal cells including vimentin, collagen type I and α-smooth muscle actin, MMP-9 and S100A4 [4••, 68, 69]. This may be due to abnormal repair resulting from repeated injury from exposure to cigarette smoke combined with episodes of recurrent infection leading to imbalance in MMPs and their inhibitors or excessive expression of extracellular matrix proteins.

The role of growth factors such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, insulin-like growth factor 2, fibroblast growth factor 2, epidermal growth factor (EGF), and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in inducing EMT has been extensively studied. Among these, TGF-β1 has been shown to induce EMT in several cell types including primary bronchial epithelial cells [70, 71], and also has a well-established role in airway remodeling. Moreover, expression of TGF-β1 is upregulated in the airways of patients with asthma [38, 72], COPD [73, 74] and pulmonary fibrosis [75]. In airway epithelial cells, TGF-β1-induced EMT is mediated by several downstream mechanisms, such as via reactive oxygen species (ROS), generation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and Smad signaling [4••, 76, 77]. In mucociliary-differentiated airway epithelial cells, TGF-β1 was shown to induce EMT through Smad2/3-dependent mechanisms, which involved upregulation of transcription factors SNAI1 and SNAI2, which represses expression of adherence and tight junction proteins [67]. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) 4, which belongs to the TGF-β1 family, was also found to induce EMT in airway epithelial cells [78]. In the context of COPD, exposure of airway epithelial cells to cigarette smoke or nicotine increases release of the active form of TGF-β1, which is dependent on ROS generation [4••]. Furthermore, the neutralizing antibody to TGF-β1, or chemical inhibitors of ERK1/2 (PD98058) and Smad3 (SIS3) completely inhibits cigarette smoke-induced EMT in mucociliary-differentiated airway epithelial cells. On the other hand, nicotine, a component of cigarette smoke, induces EMT by aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling independent of TGF-β1 [79]. Additionally, pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, whose expression is upregulated in COPD patients, synergize with TGF-β1 to enhance EMT in bronchial epithelial cells [70, 71, 80]. EMT can also be induced by bacterial or viral infections. Recently, Pseudomonas aeruginosa was shown to induce TGF-β1 driven EMT in airway epithelial cells via the activation of monocytes [81•]. In our on-going studies, we found that rhinovirus infection induces EMT in COPD, but not in normal airway epithelial cells grown at the air/liquid interface, indicating that COPD cells may respond excessively to rhinovirus infection leading to EMT (Ganesan and Sajjan, unpublished observations). Since 50–70 % of COPD exacerbations are associated with respiratory bacteria and or viruses [82, 83], it is possible that these infectious agents can accentuate EMT activity and airway remodeling in these patients.

-

2.

Epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation: Under normal conditions, following EMT, basal cells present at the edge of the wound proliferate filling the voids left by the migrating cells [59]. Proliferation of cells requires factors secreted by both resident cells and infiltrating inflammatory cells that come into the airway following injury [52]. Of the many soluble factors, members of the EGF and TGF family play a key role in proliferation of cells via activation of EGF receptor (EGFR). Activation of EGFR by exogenously added EGF ligands accelerates repair of airway epithelium in vitro [84] and similarly, inhibition of EGFR worsens acute lung injury in mice with repairing airway epithelium [85]. In normal airway epithelium, EGFR expression is low and is sequestered at the apical junctional complex by E-cadherin [86]. Following injury, the process of EMT, which is associated with decreased expression of E-cadherin, promotes uncoupling and redistribution of EGFR from the apicolateral junctional complexes to the apical cell surface [87], where EGF ligands secreted by either resident epithelial or infiltrated inflammatory cells activates EGFR readily. During normal airway epithelial repair, the activation of EGFR occurs over a very tight temporal period, with a subsequent decrease in activation. Dysregulated or persistent EGFR activation could potentially lead to abnormal repair of airway epithelium. Persistent activation of EGFR is observed in association with metaplastic or hyperplastic airway epithelium in both asthma and COPD patients [37, 88]. Recently, we demonstrated that compared to normal, COPD airway epithelial cells show aberrant activation of EGFR which contributes to increased IL-8 secretion [89••].

MMPs play a critical role in the activation of EGFR by processing EGF and EGF-like ligands to their active forms. In COPD lungs, elevated expression of MMP1, 2, 8, 9, 12 and 14 has been reported [90]. MMP9 is the predominant form in the airway epithelium and increased MMP9 activity is noted in sputum of COPD patients [91]. Both acrolein (one of the most prevailing components of cigarette smoke) and LPS (present in abundant amounts in cigarette smoke and other environmental hazards), increase the expression and activity of MMP9 in airway epithelial cells [92, 93]. Persistent exposure to cigarette smoke during injury and repair process may therefore increase EGFR activity via MMP9 leading to abnormal repair of airway epithelium.

The final stage in the regeneration of airway epithelium is the redifferentiation of proliferated cells. The generation of diversity of epithelial cells from proliferated progenitor cells are dictated in part by cell-cell interactions mediated by Notch signaling [94] and the expression of other transcription factors such as Sry-related HMG box (SOX)2 forkhead orthologue box (FOX)A2, FOXJ1, thyroid transcription factor (TTF)-1, and Sam pointed domain Ets-like factor (SPDEF) [95, 96]. SOXA2 expression, which increases after injury, promotes cell-cell contact by interacting with β-catenin, a regulator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and also positively regulates expression of cell differentiation markers Scgb1a1, FoxJ1, and Agr2 in mice [95]. Differentiation of the ciliated cells is marked by the expression of FOXJ1, which is required for the assembly of the ciliary apparatus in airway epithelial cells [95]. On the other hand, differentiation of airway goblet cells from basal or secretory progenitors requires expression of SPDEF, which regulates the expression of a network of genes associated with mucin biosynthesis and packaging of mucin granules [97, 98]. Loss of TTF1 is accompanied by increased expression of SPDEF and goblet cell hyperplasia, indicating that TTF1 may negatively regulate SPDEF expression [97]. FOXA2 is required for maintenance of normal differentiation of airway epithelial cells, as FOXA2 deletion causes goblet cell hyperplasia in vivo. In addition, overexpression of SPDEF inhibits FOXA2 and TTF1 expression indicating a complex interdependent regulation of these transcription factors that may occur during airway epithelial cell differentiation [98].

Goblet cell metaplasia and hyperplasia, which is often observed in COPD patients, may be due to dysregulated expression and/or interactions of transcription factors that play a role in cell differentiation in addition to excessive EMT. Consistent with this notion, increased expression of NOTCH1 and its upstream regulator HEY2 were observed in COPD [99•]. Increased activity of NOTCH1 signaling has been shown to promote goblet cell metaplasia via both FOXA2-dependent and independent manner [100, 101]. In patients with COPD and asthma, expression of SPDEF is increased in airway epithelial goblet cells, and this is thought to be due to increased expression of IL-13, which is a positive regulator of SPDEF [98]. Decreased expression of TTF-1 and FOXA2 was also observed in asthma, but not in COPD airways [95]. Such changes in the expression and activity of transcription factors in addition to excessive EMT are likely to alter redifferentiation of airway epithelium after injury in patients with COPD and other chronic lung disorders.

Approaches for airway epithelial repair and regeneration in COPD

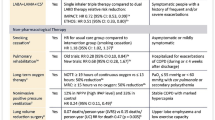

Exposure to repetitive inflammatory stimuli, which leads to exaggerated and persistent activation of repair process, is probably one of the primary causes of the airway remodeling in COPD (Fig. 2). Therefore, therapeutic interventions targeting epithelial repair and regeneration may be beneficial in these patients, and to date, no therapy has been specifically developed with the intent of repairing injured airway epithelium. Although the current therapies, which include corticosteroids and anti-inflammatory agents, provide temporary relief from respiratory symptoms and slow progression of disease minimally, they do not appear to inhibit airway remodeling in these patients. Another promising treatment strategy for correcting airway epithelial repair in COPD is stem cell therapy. In a model of acute airway epithelial injury using naphthalene, which targets non-ciliated Clara cells, bronchial progenitor/stem cells were shown migrate to the site of injury and completely repair the inured airway epithelium by 14 days [102]. In contrast, mice exposed to cigarette smoke for 5 days prior to naphthalene injury were impaired in repairing injured bronchial epithelium, indicating that cigarette smoke may either reduce the number of bronchial progenitor/stem cells or inhibit the capacity of these cells to migrate and regenerate. Therefore, treatment with competent lung progenitor/stem cells to induce a local paracrine effect through an anti-inflammatory action or by the administration of small molecules to stimulate the endogenous regenerative ability of lung cells may be beneficial in COPD [103]. Recently, a population of c-Kit positive cells with fundamental properties of stem cells was isolated from human adult lungs [104]. These cells are capable of self-renewing, clonogenic and multipotent in vitro and in vivo, indicating that these human lung stem cells may have a critical role in regeneration of lung after injury and maintaining homeostasis. However, more studies are needed to confirm the pluripotency of these cells and their capacity to regenerate the whole lungs and/or in repairing injured epithelium in chronic lung disease.

In patients with COPD, airway epithelium is constantly exposed to inflammatory stimuli such as cigarette smoke, bacteria, virus, or other environmental factors. This results in persistence of EMT, reduced number and/or migration and proliferation of basal cells and abnormal differentiation leading to remodeled airway epithelium. C Ciliated cells; Cl Clara cells; G goblet cells; B basal cells; M mesenchymal cells

Conclusions

Normal repair of airway epithelium after injury is critical for the maintenance of the airway epithelial structure and function. In patients with COPD, airway epithelium is extensively remodeled and also impaired in its function. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the airway remodeling is not completely understood, since most studies addressing airway epithelial repair have used acute injury models. Although these models provide insight into mechanisms of airway epithelial repair during acute injury, they will not address the mechanisms that are specific to chronic airway disease, such as COPD. Further, the current COPD animal models only show emphysema but not small airway remodeling, which occurs as a result of repetitive airway epithelial injury. This may be due to the fact that other host and/or environmental factors in addition to cigarette smoke may be required to induce small airway remodeling. Future studies focusing on appropriate animal model that mimics airway disease in COPD is required to identify the deregulated signaling molecules and transcription factors, and to determine the underlying cause of dysfunctional bronchial progenitor/stem cells that leads to remodeled airway epithelium with altered structure and function in COPD. Such studies may accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic targets to modulate the responses of airway epithelial cells to the inhaled environment and improve repair, as opposed to focusing on anti-inflammatory products.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

• Shaykhiev R, Otaki F, Bonsu P, et al. Cigarette smoking reprograms apical junctional complex molecular architecture in the human airway epithelium in vivo. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:877–92. This study is the first to demonstrate differences in expression of genes that encode proteins of ahderence juncitonal complexes.

•• Proud D, Hudy MH, Wiehler S, et al. Cigarette smoke modulates expression of human rhinovirus-induced airway epithelial host defense genes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40762. In this study, authors demonstrate that primary bronchial epithelial cells exposed to cigarette smoke differ from normal epithelial cells in their responses to rhinovirus infection.

Noah TL, Zhou H, Monaco J, et al. Tobacco smoke exposure and altered nasal responses to live attenuated influenza virus. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:78–83.

•• Milara J, Peiro T, Serrano A, Cortijo J. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition is increased in patients with COPD and induced by cigarette smoke. Thorax. 2013;68:410–20. This is the first study to show evidence of EMT in COPD lungs. The authors also provide evidence to show that treatment with cigarette smoke induces EMT via TGF-β.

Heijink IH, Brandenburg SM, Postma DS, van Oosterhout AJ. Cigarette smoke impairs airway epithelial barrier function and cell-cell contact recovery. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:419–28.

Selman M, Pardo A. Role of epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: from innocent targets to serial killers. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:364–72.

Tam A, Wadsworth S, Dorscheid D, et al. The airway epithelium: more than just a structural barrier. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2011;5:255–73.

Wright NA, Alison M. The biology of epithelial cell populations. Oxford University Press; 1984.

Osculati F, Bentivoglio M, Castellucci M, et al. The solitary chemosensory cells and the diffuse chemosensory system of the airway. Eur J Histochem. 2007;51 Suppl 1:65–72.

Krasteva G, Canning BJ, Hartmann P, et al. Cholinergic chemosensory cells in the trachea regulate breathing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9478–83.

Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, Chan A, et al. Bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 2008;113:5–21.

Gosney JR, Sissons MC, Allibone RO. Neuroendocrine cell populations in normal human lungs: a quantitative study. Thorax. 1988;43:878–82.

Rubin BK. Physiology of airway mucus clearance. Respir Care. 2002;47:761–8.

Randell SH, Boucher RC. Effective mucus clearance is essential for respiratory health. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:20–8.

Zeitlin PL. Cystic fibrosis and estrogens: a perfect storm. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3841–4.

Wang K, Feng YL, Wen FQ, et al. Decreased expression of human aquaporin-5 correlated with mucus overproduction in airways of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28:1166–74.

• Sloane PA, Shastry S, Wilhelm A, et al. A pharmacologic approach to acquired cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator dysfunction in smoking related lung disease. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39809. This study shows that CFTR activity is decreased in smokers with and without COPD, and activation of CFTR by ivacaftor improves CFTR activity in smokers and increase airway surface liquid hydration.

Curran DR, Cohn L. Advances in mucous cell metaplasia: a plug for mucus as a therapeutic focus in chronic airway disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42:268–75.

Schneider D, Ganesan S, Comstock AT, et al. Increased cytokine response of rhinovirus-infected airway epithelial cells in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:332–40.

Tamashiro E, Xiong G, Anselmo-Lima WT, et al. Cigarette smoke exposure impairs respiratory epithelial ciliogenesis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23:117–22.

Simet SM, Sisson JH, Pavlik JA, et al. Long-term cigarette smoke exposure in a mouse model of ciliated epithelial cell function. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:635–40.

• Yaghi A, Zaman A, Cox G, Dolovich MB. Ciliary beating is depressed in nasal cilia from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease subjects. Respir Med. 2012;106:1139–47. For the first time, authors demonstrate that ciliary beating is reduced in patients with COPD, confirming the findings of in vitro and in vivo studies.

Golec M, Reichel C, Lemieszek M, et al. Cathelicidin LL-37 in bronchoalveolar lavage and epithelial lining fluids from COPD patients and healthy individuals. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2012;26:617–25.

Pace E, Ferraro M, Minervini MI, et al. Beta defensin-2 is reduced in central but not in distal airways of smoker COPD patients. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33601.

Mallia P, Footitt J, Sotero R et al. Rhinovirus Infection Induces Degradation of Antimicrobial Peptides and Secondary Bacterial Infection in COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012.

Hodge S, Hodge G, Jersmann H, et al. Azithromycin improves macrophage phagocytic function and expression of mannose receptor in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:139–48.

Zheng S, De BP, Choudhary S, et al. Impaired innate host defense causes susceptibility to respiratory virus infections in cystic fibrosis. Immunity. 2003;18:619–30.

Zheng S, Xu W, Bose S, et al. Impaired nitric oxide synthase-2 signaling pathway in cystic fibrosis airway epithelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L374–81.

Moskwa P, Lorentzen D, Excoffon KJ, et al. A novel host defense system of airways is defective in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:174–83.

Mallia P, Message SD, Gielen V, et al. Experimental rhinovirus infection as a human model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:734–42.

Hartsock A, Nelson WJ. Adherens and tight junctions: structure, function and connections to the actin cytoskeleton. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:660–9.

Pohl C, Hermanns MI, Uboldi C, et al. Barrier functions and paracellular integrity in human cell culture models of the proximal respiratory unit. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;72:339–49.

Balda MS, Matter K. Tight junctions and the regulation of gene expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:761–7.

Koch S, Nusrat A. Dynamic regulation of epithelial cell fate and barrier function by intercellular junctions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1165:220–7.

Hogg JC, Timens W. The pathology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:435–59.

de Boer WI, Sharma HS, Baelemans SM, et al. Altered expression of epithelial junctional proteins in atopic asthma: possible role in inflammation. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;86:105–12.

Holgate ST. The sentinel role of the airway epithelium in asthma pathogenesis. Immunol Rev. 2011;242:205–19.

Holgate ST, Davies DE, Puddicombe S, et al. Mechanisms of airway epithelial damage: epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in the pathogenesis of asthma. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;44:24s–9s.

Sajjan U, Wang Q, Zhao Y, et al. Rhinovirus disrupts the barrier function of polarized airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1271–81.

Singh D, McCann KL, Imani F. MAPK and heat shock protein 27 activation are associated with respiratory syncytial virus induction of human bronchial epithelial monolayer disruption. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L436–45.

Kim JY, Sajjan US, Krasan GP, LiPuma JJ. Disruption of tight junctions during traversal of the respiratory epithelium by Burkholderia cenocepacia. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7107–12.

Kampf C, Relova AJ, Sandler S, Roomans GM. Effects of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma and IL-beta on normal human bronchial epithelial cells. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:84–91.

Coyne CB, Vanhook MK, Gambling TM, et al. Regulation of airway tight junctions by proinflammatory cytokines. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3218–34.

Hong KU, Reynolds SD, Watkins S, et al. Basal cells are a multipotent progenitor capable of renewing the bronchial epithelium. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:577–88.

Engelhardt JF, Allen ED, Wilson JM. Reconstitution of tracheal grafts with a genetically modified epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:11192–6.

Borthwick DW, Shahbazian M, Krantz QT, et al. Evidence for stem-cell niches in the tracheal epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:662–70.

Reynolds SD, Hong KU, Giangreco A, et al. Conditional clara cell ablation reveals a self-renewing progenitor function of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L1256–63.

Evans MJ, Cabral-Anderson LJ, Freeman G. Role of the Clara cell in renewal of the bronchiolar epithelium. Lab Invest. 1978;38:648–53.

Liu JY, Nettesheim P, Randell SH. Growth and differentiation of tracheal epithelial progenitor cells. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:L296–307.

Randell SH, Comment CE, Ramaekers FC, Nettesheim P. Properties of rat tracheal epithelial cells separated based on expression of cell surface alpha-galactosyl end groups. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1991;4:544–54.

Hong KU, Reynolds SD, Watkins S, et al. In vivo differentiation potential of tracheal basal cells: evidence for multipotent and unipotent subpopulations. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L643–9.

Erjefalt JS, Erjefalt I, Sundler F, Persson CG. In vivo restitution of airway epithelium. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;281:305–16.

Pilewski JM, Latoche JD, Arcasoy SM, Albelda SM. Expression of integrin cell adhesion receptors during human airway epithelial repair in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L256–63.

Dupuit F, Gaillard D, Hinnrasky J, et al. Differentiated and functional human airway epithelium regeneration in tracheal xenografts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L165–76.

Goldman MJ, Wilson JM. Expression of alpha v beta 5 integrin is necessary for efficient adenovirus-mediated gene transfer in the human airway. J Virol. 1995;69:5951–8.

Goldman MJ, Litzky LA, Engelhardt JF, Wilson JM. Transfer of the CFTR gene to the lung of nonhuman primates with E1-deleted, E2a-defective recombinant adenoviruses: a preclinical toxicology study. Hum Gene Ther. 1995;6:839–51.

Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420–8.

Buisson AC, Gilles C, Polette M, et al. Wound repair-induced expression of a stromelysins is associated with the acquisition of a mesenchymal phenotype in human respiratory epithelial cells. Lab Invest. 1996;74:658–69.

Zahm JM, Kaplan H, Herard AL, et al. Cell migration and proliferation during the in vitro wound repair of the respiratory epithelium. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1997;37:33–43.

Buisson AC, Zahm JM, Polette M, et al. Gelatinase B is involved in the in vitro wound repair of human respiratory epithelium. J Cell Physiol. 1996;166:413–26.

Coraux C, Roux J, Jolly T, Birembaut P. Epithelial cell-extracellular matrix interactions and stem cells in airway epithelial regeneration. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:689–94.

Legrand C, Gilles C, Zahm JM, et al. Airway epithelial cell migration dynamics. MMP-9 role in cell-extracellular matrix remodeling. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:517–29.

McGuire JK, Li Q, Parks WC. Matrilysin (matrix metalloproteinase-7) mediates E-cadherin ectodomain shedding in injured lung epithelium. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1831–43.

Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–54.

Wilson MS, Wynn TA. Pulmonary fibrosis: pathogenesis, etiology and regulation. Mucosal Immunol. 2009;2:103–21.

Johnson JR, Roos A, Berg T, et al. Chronic respiratory aeroallergen exposure in mice induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the large airways. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16175.

Hackett TL, Warner SM, Stefanowicz D, et al. Induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in primary airway epithelial cells from patients with asthma by transforming growth factor-beta1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:122–33.

Sohal SS, Reid D, Soltani A, et al. Reticular basement membrane fragmentation and potential epithelial mesenchymal transition is exaggerated in the airways of smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology. 2010;15:930–8.

Sohal SS, Reid D, Soltani A, et al. Evaluation of epithelial mesenchymal transition in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2011;12:130.

Camara J, Jarai G. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in primary human bronchial epithelial cells is Smad-dependent and enhanced by fibronectin and TNF-alpha. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2010;3:2.

Kamitani S, Yamauchi Y, Kawasaki S, et al. Simultaneous stimulation with TGF-beta1 and TNF-alpha induces epithelial mesenchymal transition in bronchial epithelial cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;155:119–28.

Boxall C, Holgate ST, Davies DE. The contribution of transforming growth factor-beta and epidermal growth factor signalling to airway remodelling in chronic asthma. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:208–29.

Takizawa H, Tanaka M, Takami K, et al. Increased expression of transforming growth factor-beta1 in small airway epithelium from tobacco smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1476–83.

Gao J, Zhan B. The effects of Ang-1, IL-8 and TGF-beta1 on the pathogenesis of COPD. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:1155–9.

Willis BC, Borok Z. TGF-beta-induced EMT: mechanisms and implications for fibrotic lung disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L525–34.

Yang YC, Zhang N, Van Crombruggen K, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 in inflammatory airway disease: a key for understanding inflammation and remodeling. Allergy. 2012;67:1193–202.

Gorowiec MR, Borthwick LA, Parker SM, et al. Free radical generation induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in lung epithelium via a TGF-beta1-dependent mechanism. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:1024–32.

Masterson JC, Molloy EL, Gilbert JL, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signalling in airway epithelial cells during regeneration. Cell Signal. 2011;23:398–406.

Zou W, Zou Y, Zhao Z, et al. Nicotine-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition via Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;304:L199–209.

Doerner AM, Zuraw BL. TGF-beta1 induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) in human bronchial epithelial cells is enhanced by IL-1beta but not abrogated by corticosteroids. Respir Res. 2009;10:100.

• Borthwick LA, Sunny SS, Oliphant V, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa accentuates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in the airway. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:1237–47. This study highlights the role of TGF-β1 expressed by moncytes in bacteria-induced EMT in airway epithelial cells.

Sethi S, Muscarella K, Evans N, et al. Airway inflammation and etiology of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Chest. 2000;118:1557–65.

Papi A, Bellettato CM, Braccioni F, et al. Infections and airway inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severe exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1114–21.

Puddicombe SM, Polosa R, Richter A, et al. Involvement of the epidermal growth factor receptor in epithelial repair in asthma. FASEB J. 2000;14:1362–74.

Harada C, Kawaguchi T, Ogata-Suetsugu S, et al. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibition worsens acute lung injury in mice with repairing airway epithelium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:743–51.

Qian X, Karpova T, Sheppard AM, et al. E-cadherin-mediated adhesion inhibits ligand-dependent activation of diverse receptor tyrosine kinases. EMBO J. 2004;23:1739–48.

Wendt MK, Smith JA, Schiemann WP. Transforming growth factor-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition facilitates epidermal growth factor-dependent breast cancer progression. Oncogene. 2010;29:6485–98.

Woodruff PG. Novel outcomes and end points: biomarkers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease clinical trials. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8:350–5.

•• Ganesan S, Unger BL, Comstock AT, et al. Aberrantly activated EGFR contributes to enhanced IL-8 expression in COPD airways epithelial cells via regulation of nuclear FoxO3A. Thorax. 2013;68:131–41. Authors demonstrate that airway epithelial cells isolated from COPD show increased activity, but not expression of EGFR. This study also demonstrates that inhibition of EGFR decreases proinflammatory phenotype of COPD cells.

Elkington PT, Friedland JS. Matrix metalloproteinases in destructive pulmonary pathology. Thorax. 2006;61:259–66.

Atkinson JJ, Senior RM. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 in lung remodeling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:12–24.

Jermini C, Weber A, Grandjean E. Quantitative determination of various gas-phase components of the side-stream smoke of cigarettes in the room air as a contribution to the problem of passive-smoking (author’s transl). Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1976;36:169–81.

Wang Y, Shen Y, Li K, et al. Role of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in lipopolysaccharide-induced mucin production in human airway epithelial cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;486:111–8.

Tsao PN, Vasconcelos M, Izvolsky KI, et al. Notch signaling controls the balance of ciliated and secretory cell fates in developing airways. Development. 2009;136:2297–307.

Whitsett JA, Haitchi HM, Maeda Y. Intersections between pulmonary development and disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:401–6.

Morrisey EE, Hogan BL. Preparing for the first breath: genetic and cellular mechanisms in lung development. Dev Cell. 2010;18:8–23.

Park KS, Korfhagen TR, Bruno MD, et al. SPDEF regulates goblet cell hyperplasia in the airway epithelium. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:978–88.

Chen G, Korfhagen TR, Xu Y, et al. SPDEF is required for mouse pulmonary goblet cell differentiation and regulates a network of genes associated with mucus production. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2914–24.

• Boucherat O, Chakir J, Jeannotte L. The loss of Hoxa5 function promotes Notch-dependent goblet cell metaplasia in lung airways. Biol Open. 2012;1:677–91. Here, authors show that increased Notch signaling induces goblet cell metaplasia independent of FOXA2. In addition, the authors show increased expression of NOTCH1 in COPD, suggesting that gobelt cell metaplasia observed in COPD may be due to dysregulated NOTCH signaling.

Guseh JS, Bores SA, Stanger BZ, et al. Notch signaling promotes airway mucous metaplasia and inhibits alveolar development. Development. 2009;136:1751–9.

Rock JR, Gao X, Xue Y, et al. Notch-dependent differentiation of adult airway basal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:639–48.

Van Winkle LS, Brown CD, Shimizu JA, et al. Impaired recovery from naphthalene-induced bronchiolar epithelial injury in mice exposed to aged and diluted sidestream cigarette smoke. Toxicol Lett. 2004;154:1–9.

Hind M, Maden M. Is a regenerative approach viable for the treatment of COPD? Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:106–15.

Kajstura J, Rota M, Hall SR, et al. Evidence for human lung stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1795–806.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health, HL089772 and AT004793. We thank Ms. Rachana Murthy for editing the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

Shyamala Ganesan declares no potential conflict of interest.

Uma S. Sajjan declares no potential conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ganesan, S., Sajjan, U.S. Repair and remodeling of airway epithelium after injury in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Respir Care Rep 2, 145–154 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13665-013-0052-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13665-013-0052-2