Abstract

Purpose of Review

This systematic review aims to collect evidence regarding the impact of the SarsCov-2 pandemic on people affected by eating disorders (EDs) targeting the following variables: psychopathology changes, mechanisms of vulnerability or resilience, and perception of treatment modifications during the pandemic.

Recent Findings

Since the beginning of the pandemic, a mental health deterioration has been detected in the general population and especially in people affected by pre-existing psychiatric conditions. Furthermore, mental healthcare has moved toward online treatment.

Summary

ED people showed a trend toward worsening of ED-specific psychopathology and impairment in general psychopathology. The most common vulnerability mechanisms were social isolation and feelings of uncertainty, while heightened self-care and reduced social pressure were resilience factors. The online treatment, although raising many concerns related to its quality, was considered the best alternative to the face-to-face approach. These findings may support the idea that stressful events contribute to the exacerbation of ED psychopathology and highlight the relevance of internalizing symptoms in EDs. The identification of putative risk and resilience variables as well as of subjective factors affecting online treatment perception may inform healthcare professionals and may promote more personalized approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has worldwide affected human physical and mental health [1, 2]. Several studies have detected negative effects of the pandemic on mental health in the general population [3], and the WHO declared that addressing mental health during the pandemic is a priority [4••, 5]. People affected by pre-existing psychiatric conditions were even more vulnerable to the COVID-19 infection and to develop psychiatric sequelae [6••, 7]. Previous studies from past similar outbreaks revealed that psychiatric sequelae persisted after the acute event in people at risk [8].

The COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic event, which encompasses several types of stressors, including fear of contagion, worries for relatives’ health, social distancing and isolation, disruption in routine activities and in everyday life, and change in the economic status [9,10,11]. It could be conceived as a huge psycho-social stressor with multifaceted components, and Vinkers et al. [12] suggested the opportunity for researchers to examine strategies to successfully deal with stress and adapt to the new circumstances.

People affected by eating disorders (EDs) have been considered at high risk during the COVID-19 pandemic [13•]. Indeed, since the beginning of this event, researchers have raised many concerns regarding the possible negative effects of the pandemic on ED individuals [14], since people with EDs are highly sensitive to social stress [15] and uncertainty [16] and have high need of control and difficulties in regulating emotions [17]. Rodgers et al. [18•] hypothesized that these individuals would have been vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic because of their sensitivity to disruption in daily activities and restrictions, the heightened exposure to ED-specific media messages, and their difficulty to manage fear of contagion. In the light of previous data related to people who had been quarantined in the SARS outbreak occurring in 2003 [19], an increase not only in ED-specific symptoms but also in post-traumatic stress symptoms may be hypothesized in this population. In addition to the putative psychopathology exacerbation, the researchers have also hypothesized several changes in the routine diagnostic and care strategies, including the management of medical problems resulting from their abnormal eating behaviors, discontinuation of day-hospital programs, and limitations in the access to face-to-face or group treatments with the consequent urgent need to adapt at and transit to online delivered treatments [13•, 14, 20,21,22]. Further concerns have been added regarding the accessibility of e-health services and the quality of therapeutic alliance through telemedicine [13•]. It is also worth considering that the COVID-19 pandemic has posed an increased burden on healthcare professionals [23•, 24], who need evidence-based recommendations in addition to those adapted from the pre-pandemic evidence [13•]. However, no study to date has collected literature evidence regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychopathology and treatment of people with EDs.

This systematic review aims to gather evidence from studies regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people affected by EDs exploring (1) changes in ED-specific and general psychopathology; (2) mechanisms of vulnerability and resilience to the COVID-19 pandemic exposure; and (3) change in treatment delivery service, in terms of the patients’ perception of online treatment, potential barriers and/or advantages of this method, and its effectiveness.

Methods

Information Sources and Searches

The PRISMA guidelines were followed to select and assess published articles [25].

In order to perform a systematic review of the literature, the following search keys were used in PubMed: “(COVID) AND (((eating) AND (disord*)) OR (anorexia) OR (bulimi*) OR (bing*))”. Bibliographies from relevant papers were inspected to identify studies not yielded by the initial search.

Eligibility Criteria

Articles were selected according to the following inclusion criteria: the paper (1) was a peer-reviewed research article published in English; (2) included samples of people with a current or lifetime diagnosis of any ED; and (3) was published between January 1st, 2020, and April 30th, 2021. Review papers, meta-analyses, commentary, study protocols, and case reports were excluded.

Study Selection and Data Collection Process

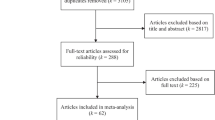

The literature search identified 696 papers, which were screened against the inclusion criteria. Fifty-two full-texts were assessed. Thirty studies were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria: fifteen were editorial/commentary/letter, six were interview of healthcare providers or caregivers, three were study protocols, three were case series, and three were conducted on general population. This resulted in the inclusion of 22 studies in the qualitative synthesis. Figure 1 reports the flow diagram of study inclusion.

Results

General Characteristics of Selected Studies

All the studies were conducted during the first wave of SarsCov-2 pandemic.

Most studies (14 of 22) were quantitative studies, 4 showed a quantitative–qualitative design, and 4 were qualitative studies. The main characteristics (diagnosis, sample size of each patients’ group, and diagnosis), the assessed outcomes, and the main findings of quantitative studies are reported in Table 1. The main qualitative findings studies are reported in Table 2.

All the selected studies, except those by Schlegl et al. [26•, 27•], Leenaerts et al. [28], and Frayn et al. [29], were conducted in mixed ED samples. Fifteen studies were conducted in patients with a current ED, 4 were in mixed samples with a current or a past ED, and 3 studies were conducted in samples with a self-reported diagnosis of an ED (1 current diagnosis, 2 current or past diagnosis). Five studies conducted a longitudinal assessment, although four of these [28, 30••, 31, 32] compared levels of symptomatology during the pandemic with those in the pre-pandemic period. The remaining studies adopted a cross-sectional design (e.g., asking participants if their symptoms had changed during the pandemic period), with the exception of 2 studies [33•, 34•] which conducted a retrospective evaluation of psychopathology. Only two studies [30••, 35] compared symptomatology levels between patients and healthy controls. Twelve studies reported that patients with EDs were in treatment, 5 did not report this data, and 3 studies were conducted in both treated and untreated patients and 2 in recently discharged patients. Three studies included outpatients, and 3 study included both inpatients and outpatients.

Seven studies reported the prevalence of SarsCov-2 infection among patients with EDs ranging from 0 to 5%.

COVID-19 Related Eating Disorder Psychopathology Effects

Most studies [14, 26•, 27•, 30••, 31, 33•, 36, 37•, 38•] identified a significant impairment in ED core symptoms (i.e., food restriction, binge-purging behaviors, and physical exercise). Considering the studies adopting a descriptive procedure, we identified a worsening of ED symptomatology occurring in a range from 38 [14] to 83% [38•] of the assessed samples. However, no change in the severity of symptomatology was found in other two studies adopting a longitudinal design [28, 32], while an improvement in eating symptoms was observed by Fernandez-Aranda et al. [39]. Worsening in the severity of symptomatology did not differ between patients with a current ED diagnosis and those with a lifetime diagnosis in two studies [37•, 40] but not in Branley-Bell and Talbot [41] who reported greater impairment in those currently ill. The studies [26•, 27•] conducted in people with a single diagnosis (AN or BN) found that almost 50% of the recruited samples reported ED symptom worsening. These studies [26•, 27•] also highlighted that when ED-related cognitions were evaluated, the impairment was even more common than that of behavioral ED symptoms, occurring in 70%, 80%, and 87% of samples with AN [27•], with BN [26•], or with mixed ED diagnoses [41], respectively. A general worsening of ED-related cognitions was also found in other studies [33•, 35]. Across ED-related aberrant behaviors, physical exercise is worth of a specific mention. Indeed, the possibility to do physical activity was reduced as result of pandemic restrictions: this promoted a widespread increase of anxiety related to inactivity effects [30••, 33•, 37•, 42] with high variability [41] in the amount of physical exercise performed by the patients.

When differences between the main ED diagnoses were investigated, a greater concern about food restriction was found in AN individuals, while more frequent binge eating was detected in the BN ones, suggesting that differences between the ED diagnoses are consistent with diagnostic characteristics [37•]. Differences between people with AN and those with BN were identified also by Castellini et al. [30••] who found that the latter group was more vulnerable to the pandemic restrictions because of their interference with the recovery process. On the other hand, three different research groups [33•, 36, 38•] failed to identify an effect of the diagnosis on the ED symptom trajectory during and after the pandemic lockdown, although the comparisons were conducted between AN individuals and mixed ED groups.

Only two studies [30••, 35] compared ED symptom impairment between people with EDs and healthy controls by employing a longitudinal approach. Castellini et al. [30••] found that the intensity of symptom (i.e., objective binge eating and physical exercise) worsening was significantly greater in patients than in controls. Nisticò et al. [35] found that the severity of ED symptom decreased in the re-opening period following the first lockdown (March to May 2020). This was consistent with the results of another study [33•] adopting a retrospective design and highlighting that in the re-opening period, the ED symptoms returned to the levels seen before the lockdown.

Limitations of these studies need to be acknowledged. First, except for Schlegl et al.’s study [27•], differences between adults and adolescents were not assessed: this precludes the possibility to predict age-related vulnerability to EDs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, only two studies adopted a prospective design and included a comparison group, and a few studies included patients with a clinically defined diagnosis. Third, most of the studies did not assess differences across the main ED diagnoses: this limits the possibility to draw transdiagnostic conclusions.

COVID-19-Related General Psychopathology and Quality of Life Effects

Changes in general psychopathology during the lockdown were assessed in 11 studies. Three of them focused on specific psychopathology variables and revealed an increase in anxiety [14, 37•] and post-traumatic stress symptoms [30••] during the lockdown period. A more comprehensive evaluation of several internalizing symptoms was conducted in the remaining studies [26•, 27•, 28, 29, 33•, 35, 42]. Overall, these studies agreed that people with EDs experienced heightened anxious and depressive symptoms during the lockdown. Schlegl et al. [26•, 27•] identified loneliness, sadness, and inner restlessness as the most pronounced general symptoms in AN and BN people with 70–75% of the assessed patients reporting a deterioration of these symptoms. Remarkably, a longitudinal design was employed in three of these studies [28, 30••, 35]. Furthermore, Monteleone et al. [33•] and Nisticò et al. [35] found that the worsening of internalizing symptoms persisted in the re-opening period that followed the first lockdown in Italy. Furthermore, an increased rate of comorbidity, affective disorders, and suicide risk was observed in children and adolescents recovered for their ED in the first months of the 2020 in comparison to those hospitalized in the same period of the previous year [31]. However, it is worth to outline that only two studies [30••, 35] adopted a prospective design and a comparison with a control group, while only Monteleone et al. [33•] included a large sample of people with EDs.

The quality of life perception was evaluated in three studies through a quantitative assessment [26•, 27•, 32]. Reduced satisfaction was observed in 62% of BN individuals and in 50% of AN people discharged from previous hospital admission [26•, 27•], while no significant change was reported by Machado et al. [32] who evaluated the ED-induced clinical impairment.

Predictors and Correlates of COVID-19-Related Psychopathology Changes

Predictors of symptom change during the COVID-19 lockdown period were evaluated in three studies adopting a quantitative design [30••, 34•, 43]. Two of these studies [30••, 43] pointed to low self-directedness, childhood traumatic experiences, and insecure attachment as predictors of the COVID-19-related ED symptoms deterioration [43] and post-traumatic stress symptoms onset [30]. In a large population with mixed ED diagnoses, the path analysis [34•] showed that heightened isolation and fear of contagion predicted ED and general symptom worsening as well as reduced satisfaction with family and with friends’ relationships and reduced perceived social support were associated with ED and general symptoms deterioration, respectively. The quality of the therapeutic relationship was a resilient factor for people with EDs [34•].

The factors related to the COVID-19 psychopathology worsening were assessed in 8 qualitative studies [29, 31, 37•, 38•, 40,41,42, 44]. Social restrictions, negative emotions, changes in routine, and thin-related social media messages were described as possible factors contributing to mental health deterioration in most of those studies. Heightened social isolation was reported in all the qualitative studies. Negative emotions included heightened rumination and anxiety [29, 38•, 40]; changes in routine activities encompassed disruption in living situation, which promoted hiding their ED from others and increased pressure from relatives to eat more [40, 41, 44], more free time with boredom and lack of distraction [38•, 40, 41], reduced opportunities to exercise [38•, 41], change in food availability at home [37•, 38•, 41], and increased intentionality and responsibility in planning their own actions [44]. These studies pointed to perceived uncertainty and lack of control as the common mechanisms by which the disruption in routine activities promoted psychopathology deterioration in ED people during the COVID-19 lockdown. However, routine changes [29, 44] and social isolation [29] were sometimes associated with symptom improvement. In this line, useful strategies helping patients to face with COVID-19-related distress were detected and can be divided in two groups: heightened self-care and reduced pressure to engage in social activities or reduced social/work pressure [29, 38•, 40, 41, 44]. The former included increased focus and responsibility for recovery [37•, 44], creating boundaries to look after self [38•], time spent in enjoyable activities/hobbies, or mild physical exercise [26•, 27•, 38•, 42].

The main limitation of the qualitative studies is their small sample sizes. Furthermore, a few studies have evaluated the effects of personality-related characteristics and of theoretically suggested variables (i.e., early abuse) that may contribute to explain the observed variation in psychopathology trajectories.

COVID-19-Related Treatment Effects

The main COVID-19-induced treatment change was a reduced access to in-person treatment [26•, 27•, 41, 42, 45]. Schlegl et al. [26•] found that the rate of BN patients receiving face-to-face treatment decreased from 82 to 36% during the lockdown. The parallel increase of online treatment was often perceived as characterized by impairment in the quality of the therapy [26•, 27•, 37•, 38•, 41, 42, 44,45,46]. In this line, Lewis et al. [45] also reported that 54% of the ED sample would not recommend the online treatment and 68% would not choose to continue the online therapy. Positive predictors of a good perception of the online therapy were longer illness duration, higher COVID-19-related anxiety, and stronger therapeutic relationship [45]. Fernández-Aranda et al. [39] found that the patients with AN were those reporting lower satisfaction with the online transition. On the other hand, a positive perception of the online therapy was reported in some other studies [29, 44, 46], and there is evidence that patients who interrupted all kinds of treatment were those showing the highest symptom worsening during the lockdown [37•]. In this line, the online treatment allowed patients to maintain a strong and safe therapeutic relationship [38•] and made treatment more accessible for some patients [29, 38•, 46]. In another study, no effect of the treatment delivery strategy (i.e., direct access or telehealth) was found on the psychopathology worsening experienced during the lockdown [34•]. The main barriers identified by the patients regarding the online treatment were perceiving a detached connection with the therapist [38•, 39, 46]; technological difficulties (e.g., low quality of Internet connection or lack of private space) [38•, 46]; and concerning about self-monitoring due to reduction of the therapist’s pressure that patients need to resist the demands of the illness [41, 46]. Overall, the online treatment was described as the best alternative when face-to-face therapy was not available [38•, 41, 46]. Finally, a few studies found that individuals with EDs described their need for mental care as less important than that for physical care related to the COVID-19 infection and perceived themselves as an unjustified burden on the health system [38•, 41, 44, 46]. It is worth mentioning that the comparison between face-to-face and telehealth therapies as well as the treatment successful rates during the pandemic has been not sufficiently explored. Although previously recommended [13•], no evaluation of self-help treatment effectiveness has been provided.

Discussion

This systematic review assessed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with EDs. A trend toward worsening of ED-specific psychopathology with respect to the pre-pandemic period was observed as well as an impairment in general psychopathology. Feeling of uncertainty was the putative common mechanism promoting mental health deterioration in individuals with EDs, although resilience mechanisms such as supporting interpersonal relationships and heightened self-care emerged. The treatment has largely moved toward online delivering strategies that, despite being considered by patients as the best alternative to the face-to-face approach, were affected by concerns about the quality of the online therapy. A wide variation in both psychopathology changes and perception of the quality of treatments has been observed among individuals with EDs.

Regarding the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychopathology, it is worth noting that ED-specific symptoms deterioration was often observed, although data were even more consistent when referring to the general psychopathology (e.g., anxiety or depressive symptoms) worsening. No differences across the main ED diagnoses were identified, although they were not deeply investigated. These data are corroborated by the increase in urgent and routine referrals of individuals with EDs and their relatives [47] as well as by the increase of in-patient admissions for EDs especially observed in adolescents [48,49,50]. This evidence may support the hypothesized post-traumatic nature of ED symptomatology, as previously suggested in experimental [51, 52] and review studies [53]. Indeed, the data collected during the pandemic have been replicated across different samples exposed to the same stressful condition, providing novel and reliable evidence of a transdiagnostic vulnerability to acute stress. More severe internalizing symptoms, primarily anxiety and depressive symptoms, were also found during the pandemic in people with EDs. Interestingly, there is some evidence [33•, 35] that their worsening persisted even in the re-opening period which followed the first lockdown, while ED-specific symptoms returned to the pre-pandemic levels. Heightened anxiety during this period may reflect the sensitivity to societal pressures which characterizes people with EDs [54]. These findings are also consistent with the widespread reported onset and/or exacerbation of affective symptoms observed during the pandemic in people with pre-existing psychiatric conditions [23•, 55]. However, they also support theoretical models [16, 56,57,58] and literature [59] describing affective symptoms as core symptoms of ED psychopathology.

It is worth noting that studies reported that some individuals with EDs remained stable in their symptoms during the lockdown, while others even improved. The inconsistency of these findings may be the result of the heterogeneity of the study methodologies: most of them included mixed ED samples with patients at different illness phases (i.e., currently ill, recovered, or discharged from hospitalization) or different treatment conditions (i.e., face-to-face or online) and different diagnostic evaluation processes (i.e., self-reported assessment of the ED diagnosis or clinically defined diagnosis). However, these findings also highlight the variability of the patients’ response to such an acute challenge and provide interesting data regarding mechanisms of resilience or illness deterioration. Although causal interpretation may be limited by the correlation nature of most of the study results, the high number of qualitative studies included in this review contributes to overcome this issue. The lack of interpersonal relationships providing security feelings and support as well as negative emotions and uncertainty feelings was the most common mechanisms making individuals with EDs more vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic. They were promoted from the disruption in routine activities (e.g., reduced time spent with friends and more with household members, familiar conflicts, increased exposure to diet-related social media messages) associated with the COVID-19-related restrictions. Unlike other psychiatric conditions [23•] and initial expectations [13•, 60], no effect of the economic condition was found on the mental health of people with EDs. On the other hand, developing new routines and planning positive (e.g., distracting) activities and having more space and time to healing and self-care and less pressure to engage in social activities were useful strategies to face with the pandemic restrictions. These findings corroborate the hypothesis that ED-related behaviors can be conceived as maladaptive coping strategies to face with emotional distress [61,62,63] and may inform clinicians about the therapeutic need to develop adaptive emotional coping strategies to promote recovery from EDs. In line with Brown et al. [44], it is also possible to suggest that the effects of restrictions may change in the light of patients’ living and work situations. This highlights the importance to consider the subjective context surrounding patients’ illness.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were observed also on the treatment. In addition to the well-known transition to the online treatment that involved all psychiatric disorders [64], this systematic review highlights that the face-to-face treatment still represents the preferred modality for individuals with EDs and that the online therapy is considered the best alternative. These findings support previous suggestions in EDs [65, 66•]. Concerns related to the telemedicine approach were related to the perception of the therapeutic relationship as more detached and impersonal as well as to some technologic barriers. However, as for the psychopathological trajectory during the pandemic, also the perception of online treatment changed across individuals with EDs, who also described this treatment as promoting more accessibility to therapies, as an opportunity to heightened and more responsible self-management of the illness and to maintain a good therapeutic relationship. COVID-19-related findings confirm the role of the therapeutic alliance as one of the most important resilience factors for individuals with EDs [67]. Finally, treatment-related data revealed a sort of self-stigma given that many patients reported feelings of guilt or being undeserving of treatment in comparison to the need of physical healthcare due to the COVID-19 disease. This is in line with the internalized stigma seen in individuals with EDs [68] and with stigma-related data for other psychiatric conditions collected during the pandemic [69] and may contribute to worsen the renowned unmet treatment needs among people with EDs [70].

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic induced several psycho-social stressors in people with EDs. Despite exacerbation of ED-specific symptomatology and deterioration of general psychopathology have been observed during this period, great variability exists among people affected by these illnesses. In this line, the identification of factors promoting variability in psychopathological change as well as in the perception of online treatment may inform researchers and healthcare professionals. Clinicians are advised to target interpersonal and emotion regulation difficulties of people with EDs and their subjective response to stressful events as well as to consider the patient’s experience of online treatments and to identify his/her potential barriers to this approach. These findings may meet the suggested need [71,72,73] for a more targeted and individualized approach for people with EDs. Finally, they can contribute to develop protocols promoting early diagnosis, recommendations for patients and therapists, and instruments to manage such an emergency period and the phase that follows.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Unützer J, Kimmel RJ, Snowden M. Psychiatry in the age of COVID-19. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:130–1. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20766.

Marazziti D, Stahl SM. The relevance of COVID-19 pandemic to psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2020;19:261–261. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20764.

Li J, Yang Z, Qiu H, Wang Y, Jian L, Ji J, Li K. Anxiety and depression among general population in China at the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:249–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20758.

•• Adhanom GT. Addressing mental health needs: An integral part of COVID-19 response. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:129–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20768. This study describes the importance to address mental health needs during the COVID-19-related public health emergency.

De Hert M, Mazereel V, Detraux J, Van Assche K. Prioritizing COVID-19 vaccination for people with severe mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2021;20:54–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20826.

•• Taquet M, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ, Harrison PJ, et al. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: Retrospective cohort studies of 62354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:130–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4. This recent study showed that survivors of COVID-19 appear to be at increased risk of psychiatric sequelae and a psychiatric diagnosis might be an independent risk factor for COVID-19.

Wang Q, Xu R, Volkow ND. Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry. 2021:20:124–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20806.

Shah K, Kamrai D, Mekala H, Mann B, Desai K, Patel RS. Focus on mental health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: Applying learnings from the past outbreaks. Cureus. 2020;12. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7405.

Tyrer P. COVID-19 health anxiety. World Psychiatry 2020;19:307–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20798.

Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Int Med. 2020;180:817–818. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562.

Rooksby M, Furuhashi T, McLeod HJ. Hikikomori: a hidden mental health need following the COVID-19 pandemic. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:399–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20804.

Vinkers CH, van Amelsvoort T, Bisson JI, Branchi I, Cryan JF, Domschke K, et al. Stress resilience during the coronavirus pandemic. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;35:12–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.05.003.

• Weissman RS, Bauer S, Thomas JJ. Access to evidence-based care for eating disorders during the COVID-19 crisis. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53:369–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23279. This article describes pre-pandemic literature evidence to help address the challenges arising from COVID-19-related disruptions in people with eating disorder.

Fernández-Aranda F, Casas M, Claes L, Bryan DC, Favaro A, Granero R, et al. COVID-19 and implications for eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2020a;28:239–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2738.

Monteleone AM, Treasure J, Kan C, Cardi V. Reactivity to interpersonal stress in patients with eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies using an experimental paradigm. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;87:133–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.02.002.

Treasure J, Schmidt U. The cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model of anorexia nervosa revisited: A summary of the evidence for cognitive, socio-emotional and interpersonal predisposing and perpetuating factors. J Eat Disord. 2013;13. https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-2974-1-13.

Mallorquí-Bagué N, Vintró-Alcaraz C, Sánchez I, Riesco N, Agüera Z, Granero R, et al. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic feature among eating disorders: Cross-sectional and longitudinal approach. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2018;26:53–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2570.

• Rodgers RF, Lombardo C, Cerolini S, Franko DL, Omori M, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating disorder risk and symptoms. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53:1166–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23318. This article hypothesized the pathways by which COVID-19 pandemic may exacerbate ED symptoms.

Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, Fan B, Kong J, Yao Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: Exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:302–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370905400504.

Todisco P, Donini LM. Eating disorders and obesity in the COVID-19 storm. Eat Weight Disord. 2021;26:747–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00938-z.

Touyz S, Lacey H, Hay P. Eating disorders in the time of COVID-19. J Eat Disord. 2020;8:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00295-3.

Andersson G, Titov N, Dear BF, Rozental A, Carlbring P. Internet-delivered psychological treatments: from innovation to implementation. World Psychiatry. 2019;18:20–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20610.

• Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395:912–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. This is a review on of the psychological impact of quarantine.

Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3:203976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gotzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869–c869. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c869.

• Schlegl S, Meule A, Favreau M, Voderholzer U. Bulimia nervosa in times of the COVID-19 pandemic—results from an online survey of former inpatients. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2020a;28:847–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2773. This article shows the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating and general psychiatric symptoms of patients with bulimia nervosa.

• Schlegl S, Maier J, Meule A, Voderholzer U. Eating disorders in times of the COVID-19 pandemic—results from an online survey of patients with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2020b;53:1791–800. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23374. This article shows the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating and general psychiatric symptoms of patients with anorexia nervosa.

Leenaerts N, Vaessen T, Ceccarini J, Vrieze E. How COVID-19 lockdown measures could impact patients with bulimia nervosa: Exploratory results from an ongoing experience sampling method study. Eat Behav. 2021;41:101505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101505.

Frayn M, Fojtu C, Juarascio A. COVID-19 and binge eating: Patient perceptions of eating disorder symptoms, tele-therapy, and treatment implications. Curr Psychol 2021:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01494-0.

•• Castellini G, Cassioli E, Rossi E, Innocenti M, Gironi V, Sanfilippo G, et al. The impact of COVID-19 epidemic on eating disorders: A longitudinal observation of pre versus post psychopathological features in a sample of patients with eating disorders and a group of healthy controls. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53:1855–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23368. This longitudinal study evaluated the impact of COVID-19 epidemic on people with eating disorder, considering the role of pre-existing vulnerabilities.

Graell M, Morón-Nozaleda MG, Camarneiro R, Villaseñor Á, Yáñez S, Muñoz R, et al. Children and adolescents with eating disorders during COVID-19 confinement: Difficulties and future challenges. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2020;28:864–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2763.

Machado PPP, Pinto-Bastos A, Ramos R, Rodrigues TF, Louro E, Gonçalves S, et al. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown measures on a cohort of eating disorders patients. J Eat Disord. 2020;8:57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00340-1.

• Monteleone AM, Marciello F, Cascino G, Abbate-Daga G, Anselmetti S, Baiano M, et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown and of the following “re-opening” period on specific and general psychopathology in people with eating disorders: The emergent role of internalizing symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2021a;285:77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.037. This study describes the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating and general psychiatric symptoms of people with eating disorders during the lockdown and in the following re-opening period.

• Monteleone AM, Cascino G, Marciello F, Abbate-Daga G, Baiano M, Balestrieri M, et al. Risk and resilience factors for specific and general psychopathology worsening in people with eating disorders during COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective Italian multicentre study. Eat Weight Disord. 2021a;1:3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01097-x. This study investigated which factors were associated with the worsening of eating and general psychiatric symptoms during the pandemic in people with eating disorders.

Nisticò V, Bertelli S, Tedesco R, Anselmetti S, Priori A, Gambini O, et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19-related lockdown measures among a sample of Italian patients with eating disorders: A preliminary longitudinal study. Eat Weight Disord. 2021;1:3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01137-0.

Phillipou A, Meyer D, Neill E, Tan EJ, Toh WL, Van Rheenen TE, et al. Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: initial results from the COLLATE project. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53:1158–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23317.

• Termorshuizen JD, Watson HJ, Thornton LM, Borg S, Flatt RE, MacDermod CM, et al. Early impact of COVID‐19 on individuals with self‐reported eating disorders: A survey of ~1,000 individuals in the United States and the Netherlands. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53: 1158–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23353. This study investigated the early impact of COVID-19 in a large sample with self-reported eating disorders.

• Vuillier L, May L, Greville-Harris M, Surman R, Moseley RL. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on individuals with eating disorders: The role of emotion regulation and exploration of online treatment experiences. J Eat Disord. 2021;9:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00362-9. This qualitative study describes the mechanisms associated with psychopathology change and the perception of online treatment during the pandemic.

Fernández-Aranda F, Munguía L, Mestre-Bach G, Steward T, Etxandi M, Baenas I, et al. COVID isolation eating scale (CIES): Analysis of the impact of confinement in eating disorders and obesity—a collaborative international study. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2020b;28:871–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2784.

McCombie C, Austin A, Dalton B, Lawrence V, Schmidt U. “Now it’s just old habits and misery”–understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with current or life-time eating disorders: A qualitative study. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:589225. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589225.

Branley-Bell D, Talbot CV. Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and UK lockdown on individuals with experience of eating disorders. J Eat Disord. 2020;8:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00319-y.

Clark Bryan D, Macdonald P, Ambwani S, Cardi V, Rowlands K, Willmott D, et al. Exploring the ways in which COVID-19 and lockdown has affected the lives of adult patients with anorexia nervosa and their carers. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2020;28:826–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2762.

Baenas I, Caravaca-Sanz E, Granero R, Sánchez I, Riesco N, Testa G, et al. COVID-19 and eating disorders during confinement: Analysis of factors associated with resilience and aggravation of symptoms. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2020;28:855–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2771.

Brown SM, Opitz MC, Peebles AI, Sharpe H, Duffy F, Newman E. A qualitative exploration of the impact of COVID-19 on individuals with eating disorders in the UK. Appetite. 2021;156:104977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104977.

Lewis YD, Elran-Barak R, Grundman-Shem Tov R, Zubery E. The abrupt transition from face-to-face to online treatment for eating disorders: A pilot examination of patients’ perspectives during the COVID-19 lockdown. J Eat Disord. 2021;9:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-021-00383-y.

Shaw H, Robertson S, Ranceva N. What was the impact of a global pandemic (COVID-19) lockdown period on experiences within an eating disorder service? A service evaluation of the views of patients, parents/carers and staff. J Eat Disord. 2021;9:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-021-00368-x.

Richardson C, Patton M, Phillips S, Paslakis G. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on help-seeking behaviors in individuals suffering from eating disorders and their caregivers. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;67:136–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.10.006.

Haripersad YV, Kannegiesser-Bailey M, Morton K, Skeldon S, Shipton N, Edwards K, et al. Outbreak of anorexia nervosa admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106:e15. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2020-319868.

Schwartz MD, Costello KL. Eating disorder in teens during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Heal. 2021;68:1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.02.014.

Solmi F, Downs JL, Nicholls DE. COVID-19 and eating disorders in young people. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2021;5:316–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366.

Monteleone AM, Ruzzi V, Patriciello G, Cascino G, Pellegrino F, Vece A, et al. Emotional reactivity and eating disorder related attitudes in response to the trier social stress test: An experimental study in people with anorexia nervosa and with bulimia nervosa. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.051.

Monteleone AM, Cascino G, Ruzzi V, Pellegrino F, Carfagno M, Raia M, et al. Multiple levels assessment of the RDoC “system for social process” in eating disorders: Biological, emotional and cognitive responses to the trier social stress test. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;130:160–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.039.

Trottier K, MacDonald DE. Update on psychological trauma, other severe adverse experiences and eating disorders: State of the research and future research directions. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0806-6.

Arcelus J, Haslam M, Farrow C, Meyer C. The role of interpersonal functioning in the maintenance of eating psychopathology: A systematic review and testable model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:156–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPR.2012.10.009.

Pierce M, McManus S, Hope H, Hotopf M, Ford T, Hatch SL, et al. Mental health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent class trajectory analysis using longitudinal UK data. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00151-6.

Treasure J, Willmott D, Ambwani S, Cardi V, Clark Bryan D, Rowlands K, et al. Cognitive interpersonal model for anorexia nervosa revisited: The perpetuating factors that contribute to the development of the severe and enduring illness. J Clin Med. 2020;9:630. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9030630.

Gross JJ, Uusberg H, Uusberg A. Mental illness and well-being: an affect regulation perspective. World Psychiatry. 2019;18:130–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20618.

Stanghellini, G. Embodiment and the Other's look in feeding and eating disorders. World Psychiatry. 2019;18:364–365. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20683.

Monteleone AM, Cascino G. A systematic review of network analysis studies in eating disorders: Is time to broaden the core psychopathology to non specific symptoms. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2834.

McIntyre RS, Lee Y. Preventing suicide in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:250–1. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20767.

Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Gordon KH, Kaye WH, Mitchell JE. Dimensions of emotion dysregulation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A conceptual review of the empirical literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;40:111–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPR.2015.05.010.

Oldershaw A, Startup H, Lavender T. Anorexia nervosa and a lost emotional self: A psychological formulation of the development, maintenance, and treatment of anorexia Nervosa. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1–22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00219.

Barlow DH, Harris BA, Eustis EH, Farchione TJ. The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:245–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20748.

Reay RE, Looi JCL, Keightley P. Telehealth mental health services during COVID-19: Summary of evidence and clinical practice. Australas Psychiatry. 2020;28:514–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856220943032.

Bauer S, Moessner M. Harnessing the power of technology for the treatment and prevention of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:508–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22109.

• Linardon J, Shatte A, Tepper H, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M. A survey study of attitudes toward, and preferences for, e-therapy interventions for eating disorder psychopathology. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53:907–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23268. This recent study explored attitudes toward, and preferences for, e-therapy among individuals spanning the spectrum of eating pathology.

Graves TA, Tabri N, Thompson-Brenner H, Franko DL, Eddy KT, Bourion-Bedes S, et al. A meta-analysis of the relation between therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50:323–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22672.

Griffiths S, Mitchison D, Murray SB, Mond JM, Bastian BB. How might eating disorders stigmatization worsen eating disorders symptom severity? Evaluation of a stigma internalization model. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51:1010–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22932.

Chaimowitz GA, Upfold C, Géa LP, Qureshi A, Moulden HM, Mamak M, et al. Stigmatization of psychiatric and justice-involved populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2021;106:110150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110150.

Austin A, Flynn M, Richards K, Hodsoll J, Duarte TA, Robinson P, et al. Duration of untreated eating disorder and relationship to outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2021;29:329–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2745.

Barber JP, Solomonov N. Toward a personalized approach to psychotherapy outcome and the study of therapeutic change. World Psychiatry. 2019;18:291–292. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20666.

Kan C, Cardi V, Stahl D, Treasure J. Precision psychiatry—what it means for eating disorders? Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2019;27:3–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2651.

Monteleone AM, Fernandez-Aranda F, Voderholzer U. Evidence and perspectives in eating disorders: a paradigm for a multidisciplinary approach. World Psychiatry. 2019;18:369–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.2067.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A. M. Monteleone, G. Cascino, and P. Monteleone; methodology, G. Cascino and A. M. Monteleone; literature search and data analysis, G. Cascino, E. Barone, and M. Carfagno; writing — original draft preparation, A. M. Monteleone; writing — review and editing, A. M. Monteleone, G. Cascino, and P. Monteleone.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Eating Disorders

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Monteleone, A.M., Cascino, G., Barone, E. et al. COVID-19 Pandemic and Eating Disorders: What Can We Learn About Psychopathology and Treatment? A Systematic Review. Curr Psychiatry Rep 23, 83 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-021-01294-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-021-01294-0