Abstract

Purpose of Review

This paper will systemically review the risk of infections associated with current disease-modifying treatments and will discuss pre-treatment testing recommendations, infection monitoring strategies, and patient education.

Recent Findings

Aside from glatiramer acetate and interferon-beta therapies, all other multiple sclerosis treatments to various degrees impair immune surveillance and may predispose patients to the development of both community-acquired and opportunistic infections. Some of these infections are rarely seen in neurologic practice, and neurologists should be aware of how to monitor for these infections and how to educate patients about medication-specific risks. Of particular interest in this discussion is the risk of PML in association with the recently approved B cell depleting therapy, ocrelizumab, particularly when switching from natalizumab.

Summary

The risk of infection in association with MS treatments has become one of the most important factors in the choice of therapy. Balance of the overall risk versus benefit should be continuously re-evaluated during treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Paper of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Neuhaus O, Farina C, Yassouridis A, Wiendl H, Then Bergh F, Dose T, et al. Multiple sclerosis: comparison of copolymer-1 reactive T cell lines from treated and untreated subjects reveals cytokine shift from T helper 1 to T helper 2 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7452–7.

Duda PW, Schmied MC, Cook SL, Krieger JI, Hafler DA. Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) induces degenerate, TH2-polarized immune responses in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:967–76.

Haas J, Korporal M, Balint B, Fritzsching B, Schwarz A, Wildemann B. Glatiramer acetate improves regulatory T-cell function by expansion of naive CD4(+)CD25(+)FOXP3(+)CD31(+) T-cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;216(1-2):113–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.06.011.

Aharoni R, Eilam R, Stock A, Vainshtein A, Shezen E, Gal H, et al. Glatiramer acetate reduces Th-17 inflammation and induces regulatory T-cells in the CNS of mice with relapsing-remitting or chronic EAE. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;225(1-2):100–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.04.022.

Spadaro M, Montarolo F, Perga S, Martire S, Brescia F, Malucchi S, et al. Biological activity of glatiramer acetate on Treg and anti-inflammatory monocytes persists for more than 10years in responder multiple sclerosis patients. Clin Immunol. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2017.06.006.

Copaxone ®. [Package insert]. Teva; November 2016.

Ford CC, Johnson KP, Lisak RP, Panitch HS, Shifronis G, Wolinsky JS, et al., Copaxone Study Group. A prospective open-label study of glatiramer acetate: over a decade of continuous use in multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2006;12(3):309–20.

Pestka S, Langer JA, Zoon KC, Samuel CE. Interferons and their actions. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:317–33.

Samuel CE. Mechanisms of the Antiviral Actions of IFN. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1988;35:27–72.

McNab F, Mayer-Barber K, Sher A, Wack A, O'Garra A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(2):87–103. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3787.

Durelli L, Conti L, Clerico M, Boselli D, Contessa G, Ripellino P, et al. T-helper 17 cells expand in multiple sclerosis and are inhibited by interferon-β. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:499–509.

Noronha A, Toscas A, Jensen M. Contrasting effects of alpha, beta, and gamma interferons on nonspecific suppressor function in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1992;31:103–6.

Venken K, Hellings N, Thewissen M, Somers V, Hensen K, Rummens JL, et al. Compromised CD4+ CD25high regulatory T-cell function in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis is correlated with a reduced frequency of FOXP3-positive cells and reduced FOXP3 expression at the single-cell level. Immunology. 2008;123:79–8.

Chen M, Chen G, Deng S, Liu X, Hutton GJ, Hong J. IFN-β induces the proliferation of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells through upregulation of GITRL on dendritic cells in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2012;242:39–46.

Ahn J, Feng X, Patel N, Dhawan N, Reder AT. Abnormal levels of interferon-gamma receptors in active multiple sclerosis are normalized by IFN-β therapy: implications for control of apoptosis. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1547–55.

Kieseier BC. The mechanism of action of interferon-beta in relapsing multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:491–502. https://doi.org/10.2165/11591110-000000000-00000.

Mirandola SR, Hallal DE, Farias AS, et al. Interferon-beta modifies the peripheral blood cell cytokine secretion in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9:824–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2009.03.004.

Rieckmann P, O'Connor P, Francis GS, Wetherill G, Alteri E. Haematological effects of interferon-beta-1a (Rebif) therapy in multiple sclerosis. Drug Saf. 2004;27(10):745–56.

Gold R, Wolinsky JS. Pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis and the place of teriflunomide. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;124(2):75–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01444.x.

Comi G, Freedman MS, Kappos L, Olsson TP, Miller AE, Wolinsky JS, et al. Pooled safety and tolerability data from four placebo-controlled teriflunomide studies and extensions. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;5:97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2015.11.006.

Aubagio tablets [US Package insert]. Genzyme Corporation, a Sanofi Company, Cambridge, Mass (2014)

O’Connor P, Comi G, Freedman MS, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of teriflunomide: Nine-year follow-up of the randomized TEMSO study. Neurology. 2016;86(10):920–30. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000002441.

Bua A, Ruggeri M, Zanetti S, Molicotti P. Effect of teriflunomide on QuantiFERON-TB Gold results. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2017;206(1):73–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00430-016-0482-x.

Albrecht P, Bouchachia I, Goebels N, Henke N, et al. Effects of dimethyl fumarate on neuroprotection and immunomodulation. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:163. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-9-163.

Scannevin RH, Chollate S, Jung MY, Shackett M, et al. Fumarates promote cytoprotection of central nervous system cells against oxidative stress via the nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;341(1):274–84. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.111.190132.

Treumer F, Zhu K, Gläser R, et al. Dimethylfumarate is a potent inducer of apoptosis in human T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121(6):1383–8.

Ghadiri M, Rezk A, Li R, Evans A, Luessi F, Zipp F, et al. Dimethyl fumarate-induced lymphopenia in MS due to differential T-cell subset apoptosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4(3):e340. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000000340.

Fleischer V, Friedrich M, Rezk A, Bühler U, Witsch E, Uphaus T, et al. Treatment response to dimethyl fumarate is characterized by disproportionate CD8+ T cell reduction in MS. Mult Scler. 2017;1:1352458517703799. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517703799.

Tecfidera [Package Insert]. Biogen. January 2017

Fox RJ, Miller DH, Phillips JT, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 or glatiramer in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1087–97.

Longbrake EE, Naismith RT, Parks BJ, Wu GF, Cross AH. Dimethyl fumarate-associated lymphopenia: Risk factors and clinical significance. Multiple sclerosis journal - experimental, translational and clinical. 2015;1:2055217315596994. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055217315596994.

Fox RJ, Chan A, Gold R, et al. Characterizing absolute lymphocyte count profiles in dimethyl fumarate–treated patients with MS: Patient management considerations. Neurology: Clinical Practice. 2016;6(3):220–9. https://doi.org/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000238.

Rosenkranz T, Novas M, Terborg C. PML in a patient with lymphocytopenia treated with dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1476–8.

Baharnoori M, Lyons J, Dastagir A, Koralnik I, Stankiewicz JM. Nonfatal PML in a patient with multiple sclerosis treated with dimethyl fumarate. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2016;3(5):e274. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000000274.

Nieuwkamp DJ, Murk JL, Cremers CH, et al. PML in a patient without severe lymphocytopenia receiving dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1474–6.

Lehmann-Horn K, Penkert H, Grein P, Leppmeier U, Teuber-Hanselmann S, Hemmer B, et al. PML during dimethyl fumarate treatment of multiple sclerosis: how does lymphopenia matter? Neurology. 2016;87(4):440–1. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000002900.

Bellizzi A, Nardis C, Anzivino E, et al. Human polyomavirus JC reactivation and pathogenetic mechanisms of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and cancer in the era of monoclonal antibody therapies. J Neurovirol. 2012;18:1–11.

Khatri BO, Garland J, Berger J, et al. The effect of dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera) on lymphocyte counts: a potential contributor to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy risk. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4:377–9.

Rubant SA, Ludwig RJ, Diehl S, Hardt K, Kaufmann R, Pfeilschifter JM, et al. Dimethylfumarate reduces leukocyte rolling in vivo through modulation of adhesion molecule expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(2):326–31.

Ulyanova T, Scott LM, Priestley GV, et al. VCAM-1 expression in adult hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells is controlled by tissue-inductive signals and reflects their developmental origin. Blood. 2005;106(1):86–94. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-09-3417.

Frohman EM, Monaco MC, Remington G, Ryschkewitsch C, Jensen PN, Johnson K, et al. JC virus in CD34+ and CD19+ cells in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(5):596–602. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.63.

Chun J, Hartung HP. Mechanism of action of oral fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(2):91–101. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181cbf825.

Cohen JA, et al. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:402–15. The first Phase III clinical study comparing fingolimod with IFN-β1a in relapsing MS.

Kappos L, Radue EW, O'Connor P, Polman C, Hohlfeld R, Calabresi P, et al., FREEDOMS Study Group. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(5):387–401. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0909494.

Tyler KL. Fingolimod and risk of varicella-zoster virus infection: back to the future with an old infection and a new drug. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(1):10–3. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3390.

Arvin AM, Wolinsky JS, Kappos L, Morris MI, Reder AT, Tornatore C, et al. Varicella-zoster virus infections in patients treated with fingolimod: risk assessment and consensus recommendations for management. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(1):31–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3065.

Issa NP, Hentati A. VZV encephalitis that developed in an immunized patient during fingolimod therapy. Neurology. 2015;84(1):99–100. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001109.

Schwanitz N., Boldt A., Stoppe M., Orthgiess J., Borte S., Sack U., and Bergh, FT. Treatment, Safety, and Tolerance: Longterm Fingolimod Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis Induces Phenotypical Immunsenescence (P2.082). April 5, 2016, 86:16 Supplement P2.082; published ahead of print April 8, 2015, 1526-632X

Veillet-Lemay GM, Sawchuk MA, Kanigsberg ND. Primary cutaneous histoplasma capsulatum infection in a patient treated with fingolimod: a case report. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;1:1203475417719043. https://doi.org/10.1177/1203475417719043.

Grebenciucova E, Reder AT, Bernard JT. Immunologic mechanisms of fingolimod and the role of immunosenescence in the risk of cryptococcal infection: a case report and review of literature. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;9:158–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2016.07.015.

Tagawa A, Ogawa T, Tetsuka S, Otsuka M, Hashimoto R, Kato H, et al. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) reactivation during fingolimod treatment for relapsing and remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;9:155–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2016.08.003.

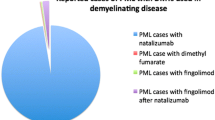

•• Berger JR, Classifying PML. risk with disease modifying therapies. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;12:59–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2017.01.006. This article reviews the most recent data of the risk of PML in association with current disease modifying treatments and establishes a classification system.

• Grebenciucova E, Berger JR. Immunosenescence: the role of aging in the predisposition to neuro-infectious complications arising from the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017;17(8):61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0771-9. This paper describes the changes that occur in the immune system with aging and suggests that clinicians should consider patient’s age when assessing patient’s risk of infection in association with specific disease modifying therapies.

Elices MJ, Osborn L, Takada Y, et al. VCAM-1 on activated endothelium interacts with the leukocyte integrin VLA-4 at a site distinct from the VLA-4/fibronectin binding site. Cell. 1990;60:577–84.

Lobb RR, Hemler ME. The pathophysiologic role of α4 integrins in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1722–8.

Carotenuto A, Scalia G, Ausiello F, Moccia M, Russo CV, Saccà F, et al. CD4/CD8 ratio during natalizumab treatment in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neuroimmunol. 2017;309:47–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.05.006.

Stüve O, Marra CM, Bar-Or A, Niino M, Cravens PD, Cepok S, et al. Altered CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratios in cerebrospinal fluid of natalizumab-treated patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(10):1383–7.

Kobeleva X, Wegner F, Brunotte I, Dadak M, Dengler R, Stangel M. Varicella zoster-associated retinal and central nervous system vasculitis in a patient with multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-11-19.

Mulero P, Auger C, Parolin L, Fonseca E, Requena M, Rio J, et al. Varicella-zoster meningovasculitis in a multiple sclerosis patient treated with natalizumab. Mult Scler. 2017;1:1352458517711569. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517711569.

Yeung J, Cauquil C, Saliou G, Nasser G, Rostomashvili S, Adams D, et al. Varicella-zoster virus acute myelitis in a patient with MS treated with natalizumab. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1812–3. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182918d27.

Haggiag S, Prosperini L, Galgani S, Pozzilli C, Pinnetti C. Extratemporal herpes encephalitis during natalizumab treatment: A case report. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;10:134–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2016.10.002.

Fine AJ, Sorbello A, Kortepeter C, Scarazzini L. Central nervous system herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus infections in natalizumab-treated patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(6):849–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit376.

•• TYSABRI® (natalizumab) Safety. Updated June 2017. Available at: https://medinfo.biogen.com/secure/download?doc=workspace%3A%2F%2FSpacesStore%2Fa22baae1-7220-416c-8c2c-28c42cdacff8&type=pmldoc&path=null&dpath=null&mimeType=null. Accessed on July 29, 2017. This is an important update relating to Tysabri safety information that clinicians should familiarize themselves with.

Antoniol C, Jilek S, Schluep M, Mercier N, Canales M, Le Goff G, et al. Impairment of JCV-specific T-cell response by corticotherapy: effect on PML-IRIS management? Neurology. 2012;79(23):2258–64. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182768983.

Lee P, Plavina T, Castro A, Berman M, Jaiswal D, Rivas S, et al. A second-generation ELISA (STRATIFY JCV™ DxSelect™) for detection of JC virus antibodies in human serum and plasma to support progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy risk stratification. J Clin Virol. 2013;57(2):141–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2013.02.002.

Subramanyam M, Plavina T, Khatri BO, Fox RJ, Goelz SE. The effect of plasma exchange on serum anti-JC virus antibodies. Mult Scler. 2013;19(7):912–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458512467502.

Plavina T, Subramanyam M, Bloomgren G, Richman S, Pace A, Lee S, et al. Anti-JC virus antibody levels in serum or plasma further define risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(6):802–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24286.

Kuesters G, Plavina T, Lee S, et al. Anti-JC virus (JCV) antibody index differentiates risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in natalizumab-treated multiple sclerosis (MS) patients with no prior immunosuppressant (IS) use: an updated analysis (P4.031). Neurology. 2015;84:suppl P4.031.

Schwab N, Schneider-Hohendorf T, Melzer N, Cutter G, Wiendl H. Natalizumab-associated PML: Challenges with incidence, resulting risk, and risk stratification. Neurology. 2017;88(12):1197-1205. doi: https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003739.

Miranda Acuña JA, Weinstock-Guttman B. Influenza vaccination increases anti-JC virus antibody levels during treatment with Natalizumab: case report. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;9:54–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2016.06.014.

Kappos L, Li D, Calabresi PA, O'Connor P, Bar-Or A, Barkhof F, et al. Ocrelizumab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9805):1779–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61649-8.

Sorensen PS, Blinkenberg M. The potential role for ocrelizumab in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: current evidence and future prospects. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2016;9(1):44–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756285615601933.

Henegar CE, Eudy AM, Kharat V, Hill DD, Bennett D, Haight B. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic literature review. Lupus. 2016;25(6):617–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203315622819.

Montalban X, Hauser SL, Kappos L, Arnold DL, et al. ORATORIO clinical investigators. Ocrelizumab versus placebo in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(3):209–20. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1606468.

Hauser SL, Bar-Or A, Comi G, Giovannoni G, et al. Ocrelizumab versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(3):221–34. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1601277.

Bouaziz JD, Yanaba K, Venturi GM, Wang Y, Tisch RM, Poe JC, et al. Therapeutic B cell depletion impairs adaptive and autoreactive CD4+ T cell activation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(52):20878–83.

Lykken JM, DiLillo DJ, Weimer ET, et al. Acute and chronic B cell depletion disrupts CD4+ and CD8+ T cell homeostasis and expansion during acute viral infection in mice. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2014;193(2):746–56. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1302848.

Cross AH, Stark JL, Lauber J, Ramsbottom MJ, Lyons J-A. Rituximab reduces B cells and T cells in cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis patients. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2006;180(1-2):63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.06.029.

Hughes S. PML Reported in Patient Receiving Ocrelizumab. Medscape. May 25, 2017. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/880654. Accessed on July 10, 2017.

• Fine AJ, Sorbello A, Kortepeter C, Scarazzini L. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab discontinuation. Ann Neurol. 2014;75(1):108–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24051. This is an important study that illustrates the carry-over risk of PML after natalizumab discontinuation.

Buch MH, Smolen JS, Betteridge N, et al. Updated consensus statement on the use of rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2011;70(6):909–20. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2010.144998.

Clifford DB, Ances B, Costello C, et al. Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Archives of neurology. 2011;68(9):1156–64. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2011.103.

Kim SH, Hyun JW, Jeong IH, Joung A, Yeon JL, Dehmel T, et al. Anti-JC virus antibodies in rituximab-treated patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. J Neurol. 2015;262(3):696–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-014-7629-8.

Tsuji H, Yoshifuji H, Fujii T, Matsuo T, Nakashima R, Imura Y, et al. Visceral disseminated varicella zoster virus infection after rituximab treatment for granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;27(1):155–61. https://doi.org/10.3109/14397595.2014.948981.

Coles A, Deans J, Compston A. Campath-1H treatment of multiple sclerosis: lessons from the bedside for the bench. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2004;106:270–4.

Lemtrada [package insert]. Cambridge, MA. Genzyme. April 2017.

Isidoro L, Pires P, Rito L, Cordeiro G. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia treated with alemtuzumab. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;8:2014. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-201781.

Keene DL, Legare C, Taylor E, Gallivan J, Cawthorn GM, Vu D. Monoclonal antibodies and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Can J Neurol Sci. 2011;38(4):565–71.

•• Centers for disease control and prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 13th edition. Appendix B-4. May 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/appendices/b/us-vaccines.pdf Last accessed on July 31, 2017. As questions of which vaccines are safe during the specific disease modifying treatments frequently arise, clinicians should familiarize themselves with an extensive table of vaccines and their inactive or attenuated/ live status.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Amy Pruitt declares no conflict of interest.

Elena Grebenciucova has received James T. Lubin Clinician Scientist Fellowship Award from the Transverse Myelitis Association dedicated to promising research and exceptional clinical care for rare neuro-immune disorders, such as transverse myelitis, including acute flaccid myelitis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, neuromyelitis optica, and optic neuritis.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Infection

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grebenciucova, E., Pruitt, A. Infections in Patients Receiving Multiple Sclerosis Disease-Modifying Therapies. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 17, 88 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0800-8

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0800-8