Abstract

In coastal dunes, shrub encroachment disrupts natural disturbance, and reduces habitat heterogeneity and species composition. In this paper, we implemented a pilot scale trial aimed at restoring coastal dunes affected by the encroachment by the shrub Retama monosperma (hereinafter Retama) as well as strengthening the populations of Thymus carnosus (regionally cataloged as ‘Critically Endangered’). A total 3 ha of Retama shrub was clearcut in two sites with different Retama cover (54 and 72%). The effect of rabbits on vegetation recovery was assessed by placing exclosures both in treated and untreated plots in Spring, 2015. Plant composition, species richness and diversity were evaluated two years after treatments (with and without Retama clearing, and with and without rabbit exclusion). Retama clearing alone did not allow the recovery of plant composition typical of gray dunes two-years after treatments, but resulted in a biodiversity loss within the Retama understorey when rabbits were present. However, Retama clearing resulted in a significant vigor improvement of T. carnosus in the site with the highest density of Retama. Rabbit exclusion significantly increased species richness and Shannon-Wiener diversity index, and allowed the recovery of plant composition typical of gray dunes. The results suggest that shrub encroachment caused by Retama has a long-lasting negative impact on dune vegetation and that periodic clearing should be combined with rabbit exclusion at least during early restoration stages of dune vegetation. To recover the population of T. carnosus, Retama should be prevented from reaching high cover and periodic clearing without rabbit exclusion is suggested.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In coastal dunes, shrub encroachment disrupts natural disturbance, and reduces habitat heterogeneity and species composition. The coastal dunes are ecosystems of great interest for conservation due to their high ecological diversity (Martínez et al. 2004; Van der Maarel 2003) and the provision of important ecosystem services such as coastal protection, freshwater supply, recreation and biodiversity conservation (Everard et al. 2010). Coastal dunes are also the ecosystems where degradation is greatest due to human activity (Martínez et al. 2013; Nordstrom et al. 2000). Fixation or stabilization (generally through the planting of herbaceous or woody species) have been often promoted to reduce dune erosion and to slow down the advance of blowing transgressive sand sheets (Pye 1983). However, stabilization and encroachment disrupts environmental heterogeneity, biodiversity and natural disturbance (Avis 1995; Isermann et al. 2007; Muñoz-Vallés et al. 2014; Wouters et al. 2012) thus outcompeting the community adapted to naturally disturbed habitats (Martínez et al. 2013). Moreover, the competitive displacement of threatened species by common species poses a conservation dilemma: should natural habitats be managed to prioritize the conservation of threatened species or should they be allowed to evolve with minimal human intervention, even if this leads to the extinction of an endangered species? In an increasingly fragmented territory, environmental management is posed to conserve as much biodiversity as possible.

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, Pinus pinea and R. monosperma (hereinafter ‘Retama’) have been planted extensively in the coastal dunes of southwestern Spain (Kith-Tasara 1946; Martínez and Montero 2004; Muñoz-Vallés et al. 2014; Muñoz-Reinoso 2021). Both species are native in the region but have been deliberately introduced outside their original forest areas (Martínez and Montero 2004; Talavera 1999). Once introduced, Retama is dispersed by rabbits and cattle (goats) (Dellafiore et al. 2006; Zunzunegui et al. 2012). The areas initially planted and the adjacent areas where these species have expanded have severely reduced the habitat dominated by fixed, stable sand dunes that are covered by herbaceous vegetation (hereinafter, ‘gray’ dunes) (Muñoz-Vallés et al. 2013; Gallego-Fernández et al. 2015), as occurred in other European coastal areas (Houston 2008). Gray dunes are a priority habitat type of the European Union that demand conservation and management actions (Gracia and Muñoz 2009). Furthermore, Retama has drastically affected the populations of Thymus carnosus (herainafter ‘Thymus’) (Zunzunegui et al. 2012), which is currently protected by European (EU Directive 92/43/CEE), National (Royal Decree 139/2011) and Regional (Decree 23/2012) regulations.

Retama monosperma is a species native to the southwestern Iberian Peninsula and northwestern Morocco (Talaver a 1999). Retama formations constitute a European natural habitat type (Thermo-Mediterranean and pre-desert scrub; European Commission 2013). However, in certain sites where this species was artificially planted, Retama encroachment may pose a threat to coastal dune ecosystems. This encroachment is the result of plantings made in the early 1920s, when tree plantations aimed at stabilizing ‘non-productive’ coastal sand dunes (Martínez and Montero 2004). Moreover, gray dunes are considered habitats of priority community interest and often contain rare species (Isermann 2011), as shown by the presence of Thymus carnosus in the present study. Thus, management actions on this growing problem are required to preserve mobile and gray dunes and the endangered, protected Thymus. The growth of Retama reduces both the light penetration and air temperature and increases both the relative humidity under its canopy. In addition, this N-fixing species increases nutrient concentration in the soil (Muñoz-Vallés et al. 2011, 2013; Esquivias et al. 2015), thus entailing an important disruption of nutrient-poor habitats. This way Retama expansion outcompetes psammophilous species typical of gray dunes (including Thymus) (Muñoz-Vallés et al. 2011; Muñoz-Vallés and Cambrollé 2015). The further expansion of Retama mediated by rabbits (Dellafiore et al. 2006) would also compromise the future colonization of Thymus in the new expanding dunes.

In this paper, we show the first results of management actions aimed at restoring the gray dunes affected by Retama encroachment and at preserving Thymus. The effects of Retama clearing and rabbit exclusion on coastal dune vegetation and the endangered Thymus were assessed in the short term (two years). Specifically, we aimed at answering the following questions: 1) What is the response of plant community typical of fixed (gray) dunes after Retama clearing; 2) Do rabbits have a positive or a negative role in the recovery of plant community?; 3) How Retama and rabbits should be managed to promote Thymus conservation? These results can serve as a basis for the management and restoration of coastal habitats affected by shrub encroachment.

Methods

Area of study

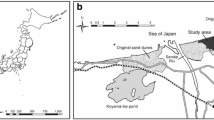

The study was carried out in a coastal dune system located at El Rompido spit (N 37° 12′, W 7° 07′, SW Spain, Fig. 1). It is a sandy formation associated with the mouth of the Piedras River, which has evolved from a barrier island system (active in the eighteenth century), its width varying from 300 to 700 m, and steadily growing to East at mean annual rate of ca. 40 m per year (1.5 ha/year) (Muñoz-Vallés et al. 2009, 2011). The climate is Mediterranean, with an influence from the Atlantic Ocean. Mean annual temperature is 18.2 °C and mean annual rainfall is 583 mm (AEMET 2019). The outstanding conservation value of this site is recognized in its designation as Regional Protected Area, Site of Scientific Interest and Special Area of Conservation under the EC Habitats and Species Directive 1992. The spit stretches eastwards for 12 km running parallel to the coastline, and currently covers an area about 500 ha. The xeroseries starts with embryonic shifting dunes covered with sparse vegetation, dominated by Elytrigia juncea subsp. boreoatlantica. This is followed by mobile, active dunes or foredunes (hereinafter referred as ‘yellow’ dunes) usually with one single ridge (ca. 5 m high). Both the sea side and downwind of yellow dunes is dominated by Ammophila arenaria subsp. australis, Achillea maritima, Artemisia campestris subsp. maritima, Lotus creticus and Pancratium maritimum (Muñoz-Vallés et al. 2015). The yellow dunes give way landwards to fixed, stable sand dunes that are covered by herbaceous vegetation and small shrubs under less disturbed conditions, with a lower sand accumulation and a flatter relief. Gray dune include a grass community dominated by Malcolmia littorea, Echium gaditanum, Polycarpon alsinifolium, L. creticus and Carduus meonanthus and, in more mature stages, Helichrysum italicum subsp. picardii, Euphorbia terracina and Anthemis maritima. These gray dune xeroseries contain the endangered Thymus carnosus. Thymus has a distribution range restricted to the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula, with two main nuclei, one located between Lisbon and Sines (Portugal), and the other from Faro (Portugal) to Huelva (Spain). Thus, the area of study houses the easternmost population of this species globally (Muñoz-Vallés et al. 2009). Gray dunes and even the downwind of the yellow dunes are being colonized by a Retama shrubland (Muñoz-Vallés et al. 2014). Retama extends to the transition zone with the upper saltmarsh (which is marked by the presence of Salsola spp.). The study area was partially planted with Retama in the 1920s (Gallego-Fernández et al. 2006). Since then, Retama has spreaded extensively, and currently occupies 96% of the dunes. This expansion has considerably modified the composition of dune plants since just some nitrophilous annuals grow in the Retama understorey (Muñoz-Vallés et al. 2011, 2015).

a-b Area of study showing the distribution of clearcut sites and local patches of Thymus carnosus throughout the Site of Community Importance and Special Protection Area ‘Marismas del Río Piedras and Flecha del Rompido’ (diagonal-hatch pattern); Detail of sites 1 (c) and 2 (d), showing clearcut areas (white line), control (untreated) areas (diagonal-hatch) and rabbit exclosures (cross-hatch pattern)

Clearing of Retama and rabbit exclusion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the response of native plant community after a drastic reduction of Retama cover and to assess the role of rabbits in gray dune restoration. Two 1.5 ha sites with different Retama cover were selected: site 1 had a mean (± SD) Retama cover of 56 ± 27%, whereas site 2 had a cover of 72 ± 24% (data obtained in n = 30 transects of 25 m for each site) (Fig. 1). Also, sites 1 and 2 differed in the composition of the plant community as shown in Tables S1, S2 and S3. The treatment, carried out in April 2015, consisted of cutting the stems directly at the ground of most of the Retama individuals to decrease its cover to ca. 10%. The roots were not removed because the heavy machinery could have damaged numerous individuals of Thymus, which were often intermingled with Retama. Preferentially, young and medium-sized individuals (diameter < 3.5 m) that showed lower shading and litter accumulation compared to senescent individuals were left unfelled. Felling was carried out with portable gasoline chainsaws. The felled biomass was burned in situ over areas previously covered by the canopy of Retama but leaf litter was not removed. After clearing Retama, rabbit exclosures were placed in site 1 (Fig. 1c). Exclosures had a mesh size of 2.5 cm, a height of 1 m, and a distance between piles of 3 m. The fence was buried 0.3 m below ground to prevent rabbits from entering the exclosures by digging. The size and shape of rabbit exclosures (500-4000 m2) were adapted to the spatial distribution of Thymus. Each exclosure included at least 30 Thymus individuals. To have an estimate of rabbit density in the study area, the number of warrens and used entrances for each warren were counted in 20-m belt transects (total length = 2.36 km) (Fig. 1b), according to Palomares (2001). Rabbit density was then estimated following Fernández-de-Simon et al. (2011) using the equation y = 0.025x, where y is the number of rabbits ha−1 and x is the number of warren entrances km−1.

Experimental design

The effect of Retama clearing on dune vegetation was evaluated two years after treatment. In site 1, we also assessed the effect of rabbits on the plant community. A total of 750 1 × 1 m plots were established at sites 1 and 2 in April 2017. Plots were established both within the Retama understorey (i.e., shaded habitat beneath the Retama canopy, hereinafter ‘under’) and in areas located ≥2 m away from the understorey (i.e., sun-exposed dunes, hereinafter ‘sun’). The following treatments were set and compared (n = 50–100 plots per treatment; Fig. 2):

-

In site 1 (Retama cover = 56%): treatment 1 (control, 1 T1): with rabbits and Retama; treatment 2 (T2): with rabbits and clearcut Retama; treatment 3 (T3): without rabbits and Retama; treatment 4 (T4): without rabbits and cleacut Retama. In each treatment, vegetation features were analyzed both in sun-exposed dunes (hereinafter identified with the subscript ‘sun’), and within the Retama understorey (hereinafter identified with the subscript ‘under’). As a result, in site 1 we analyzed the following treatments: T1sun, T2sun, T3sun, T4sun, C1under, T2under, T3under and T4under (Fig. 2).

-

In site 2 (Retama cover = 72%): treatment 5 (control, T5): with rabbits and Retama (understorey); treatment 6 (T6): with rabbits and clearcut Retama (sun-exposed dunes and Retama understorey). As a result, in site 2 we analyzed treatments T5under, T6sun and T6under. The absence of sun-exposed dunes with (untreated) Retama in this site made unfeasible to analyze a control T5sun.

All treatments shared similar slope and substrate characteristics. The frequency of each plant species was calculated from presence data obtained in n = 50 to 100 1 × 1 m quadrats (depending on the size of each treatment, we measured the presence of each species in a minimum of 50 quadrats and a maximum of 100 quadrats). Samplings were done in spring (April, 2017) to record spring ephemerals and woody, perennial plants. Plant determinations followed Flora Iberica (Castroviejo 1986-2012) except for families Gramineae and Compositae (not included in Flora Iberica) for which a different guide was used (Valdés et al. 1987). Nomenclature was checked using the Plantlist database (http://www.theplantlist.org/). From community composition data obtained we calculated the species richness (S), the Shannon-Weaver’s diversity index (H´), the dominance index (D) and the Buzas and Gibson’s evenness index (eH´/S, where H´ is the Shannon’s diversity index) corresponding to each treatment. The former indices value all species equally and do not evidence shifts in composition. Thus, multivariate tests SIMPER and one-way ANOSIM were applied to get complementary information of plant community composition. The SIMPER test calculates the percentage of dissimilarity between pairs of treatments, as well as the contribution of each species to overall dissimilarity. ANOSIM is a non-parametric test that assesses the overall significance of the difference between predefined groups (treatments) by reporting significance (p) and R values. The R statistic compares average similarities within groups and between groups. R values theoretically varies between −1 and 1. R values close to 1 indicate high dissimilarity between groups while close to 0 values indicate no differences in community composition between treatments (Clarke and Warwick 2001).

Response of Thymus to Retama clearing and rabbits

All Thymus individuals included in sites 1 and 2 were numbered before treatments with an aluminum plate attached to the main stalk. Since Thymus is a long-living perennial plant, significant changes in its abundance were not expected within the duration of the experiment. Thus, the vigor of Thymus individuals was measured and compared before (May, 2015) and two years after treatments (May 2017) in different treatments. In this case, no distinction was made between sub-environments (sun-exposed or understorey) since Thymus normally appeared in sun-exposed dunes but also in close proximity to Retama. Five vigor categories were established based on the percentage of green stems in plant: totally dry (0); proportion of green stems = 1-20% (1), 21-40% (2), 41-60% (3), 61-80% (4), and > 81% (5). For comparison, the variation of vigor (ΔV) was obtained by subtracting the vigor category measured in 2017 (V2017) from the vigor category in 2015 (V2015) (Eq. 1). Thus, ΔV < 0 indicates that Thymus underwent a vigor decrease, while ΔV > 0 indicates an improvement in the plant vigor. ΔV = 0 means that the plant did not show any vigor change between 2017 and 2015.

Statistical analysis

Normality and equality of variances were analyzed by Shapiro-Wilk and Levene tests. The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to compare the medians of S, H´, the dominance index, the Buzas and Gibson’s evenness index, and ΔV of Thymus between years (before and after treatments). Sites 1 and 2 were analyzed separately. When significant differences existed, pairwise analysis was done with the Mann-Whitney U test. Differences were considered significant when p ≤ 0.05. Multivariate analyses SIMPER and ANOSIM were used to compare plant community response to clearcutting and rabbit grazing based on the identity of all plant species present in the treatments. Both multivariate analyses were based on the Bray-Curtis similarity measure. Bonferroni corrected p values and R statistic values were obtained by Anosim test. The software Past3 was used (Hammer 2001).

Results

The clearcut of Retama scrub increased the percentage of bare sand areas notably (from a Retama cover of 54% in site 1 and 72% in site 2 to ca. 10% after treatments) (Figs. 1c-d). Retama showed massive resprouting (89% of felled Retama individuals). Consequently, additional clearings were implemented 12, 30 and 48 months after initial felling. These clearings were considered part of the treatment to maintain the reduction of Retama cover initially established. Based on active warrens counts, rabbit density in the study area was 0.9 rabbits ha−1.

In site 1, Retama clearing and rabbit exclusion significantly increased S and H´, both in sun-exposed dunes and within the Retama understorey. Accordingly, dominance showed a significant decrease and a significant increase of evenness. In contrast, when rabbits were present, Retama clearing significantly reduced S and H´ in the Retama understorey (Figs. 3a, b). The absence of rabbits alone (in treatments with Retama) significantly increased H´ in sun-exposed dunes (Fig. 3b). Curiously, Retama clearing resulted in a significant decrease of both S and H´ within the understorey (Figs. 3a-b). Table 1 shows an overview of the effect of the different treatments in species richness, the diversity index and Thymus vigor.

Effect of Retama clearcutting and rabbit exclusion on species richness (S) and Shannon-Weaver diversity index (H´). The different treatments compared were: In site 1: T1: untreated Retama with rabbits; T2: clearcut Retama with rabbits; T3: untreated Retama without rabbits; and T4: clearcut Retama without rabbits. Plant community of sun-exposed dunes (‘sun’) and Retama understorey (‘under’) in the different treatments were analysed separately. In site 2: T5: untreated Retama with rabbits, understorey; T6: clearcut Retama with rabbits (sun-exposed dunes and Retama understorey). Significant differences between plot pairs are indicated: *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01. Each box plot represents the median (Q2), Q1 and Q3 of n = 50 to 100 quadrats (N = 750)

Retama clearing (with rabbits) resulted in significant differences in plant composition, either in sun-exposed dunes (T1sun vs. T2sun; Anosim test) or within the Retama understorey (T1under vs. T2under; ANOSIM test), however, R values <0.5 suggested that these differences were rather poor (Table 1). Similarly, in cleared Retama treatments, rabbit exclusion caused significant differences in plant composition in both sub-environments (T2sun vs. T4sun and T2under vs. T4under, respectively; ANOSIM test). In this case, R values close to 1 suggested that rabbits were a strong factor explaining such differences (Table 1). However, rabbit exclusion alone (without Retama clearing) did not caused significant differences in plant composition either in sun-exposed dunes (T1sun vs T3sun) or within Retama understorey (T1under vs T3under) (Table 1). Similarly, in absence of rabbits, Retama clearing did not show significant changes in plant composition, whatever the subenvironment considered (see T3sun vs T4sun and T3under vs T4under in Table 1). Rabbits showed a clear food selection for annual non-spiny plant species. In treatments with rabbits (T1sun, T1under, T2sun and T2under), plant community was dominated by spiny species such as Carduus meonanthus and Echium gaditanum (Tables S1, S2). In fact, E. gaditanum showed a sharp increase after Retama clearing (T2sun, T2under, T4sun and T4under) whereas rabbit exclosures (T3sun, T3under, T4sun and T4under) were colonized by a diverse plant community including L. creticus, Erodium cicutarium, Malcolmia littorea and Medicago littoralis (Tables S1, S2; Fig. 4).

In site 2, sun-exposed dunes (T6sun) were dominated by Helichrysum italicum subsp. picardii, whereas the Retama understorey was dominated by annuals such as Carduus meonanthus, Sonchus oleraceus and Centranthus calcitrapa (Table S3). As in site 1, Retama clearing resulted in a significant decrease of both S and H´ within the Retama understorey (T5under vs T6under in Fig. 3c-d, Table 1), however, plant composition was very similar (dissimilarity percentage = 35%, SIMPER test) and no significant differences were apparent (Table 1), besides a slight increase in the abundance of the therophyte S. oleraceus. P6under showed significantly lower S and H´ than P6sun (Fig. 3c-d). Untreated Retama understorey (P5under) and P6sun showed similar S and H´ values, however, their plant community composition showed high dissimilarity percentages (89%), as well as significant differences and R values close to 1 (Anosim test).

Finally, we observed a significant increase in Thymus vigor after two years only in clearcut areas previously colonized by a high density of Retama (T5 vs T6, Fig. 5). In contrast, Thymus showed a significant vigor loss inside rabbit exclosures with untreated Retama with respect to control Retama plots with rabbits (T1 vs T3; Fig. 3).

Discussion

The present study provides the first management experiences aimed at restoring coastal dunes affected by Retama encroachment. Our results suggest that shrub encroachment caused by Retama has a long-lasting negative impact on dune vegetation. In addition, we show that the drastic reduction of the coverage of Retama and the exclusion of rabbits significantly influence the change in composition and abundance of species of the plant community and favor the growth of the threatened species Thymus, promoting the restoration of dune vegetation.

Retama clearing alone did not allow the recovery of plant composition typical of gray dunes two-years after treatments, but resulted in a biodiversity loss within the Retama understorey when rabbits were present. Several studies reported an increase of species richness and diversity, including the recovery of species specific to open dune habitats (Kutiel et al. 2000; Marchante et al. 2011a) following removal of shrubs (either native or invasive) without further rabbit exclusion, whereas other studies reported a very little effect (Bird et al. 2020). In addition, we found repeated resprouting of Retama after felling. Resprouting after fire or seawater flooding have been reported in Retama species (Muñoz-Vallés et al. 2013), but resprouting rates found in the present study for R. monosperma were higher than values reported after felling in Retama raetam from western Australia (Bettink and Brown 2011). The recovery of plant community typical of gray dunes was particularly poor within the understorey of clearcut Retama, suggesting that higher organic matter and nutrient concentrations may persist for more than two years (Marchante et al. 2011a; Muñoz-Vallés et al. 2011). Accordingly, the removal of leaf litter along with plants might promote a faster recovery of dune vegetation (Marchante et al. 2011b; Pickart et al. 1998).

Our study showed that Retama clearing alone was not enough to restore dune vegetation, but strongly depended on the presence of rabbits. Also, both S and H´ significantly increased in plots with rabbits exclusion (with or without Retama clearing) suggesting that rabbits may compromise restoration of plant community typical of gray dunes. Our results agree with Moulton et al. (2019) who found an increase in vegetation cover in southern Australia dunes (where rabbits are an invasive alien species) coinciding with a decrease of rabbit density. In general, grazing favor habitat heterogeneity (by opening patches or scrapes) (Burggraaf-van Nierop and van der Meijden 1984; Isermann et al. 2010), and slows succession (Millett and Edmondson 2013). Consequently, the increase of rabbit density has been proposed to reduce grass and shrub encroachment (Houston 2008; Kooijman and de Haan 1995; Kooijman et al. 2017). However, this apparently general trend of ‘less rabbits-more vegetation’ may not follow a linear correlation regarding species richness, diversity and composition. The highest plant richness was reached at intermediate levels of grazing pressure, in agreement with the general statement of maximum diversity with intermediate disturbance levels (Isermann et al. 2010). In the present study, rabbits outside the exclosures fed anything that doesn’t have spines or skewers and promoted the development of grasslands dominated by the spiny species Carduus meonanthus and Echium gaditanum, thus favoring the development of a species-poor community of therophytes. In sand dunes from Belgium, rabbits exclusion resulted in a dense and high vegetation with dominance of a few grass species, negatively affecting annuals such as Arenaria serpyllifolia and Phleum arenarium (Somers et al. 2005). This observation agrees with previous reports of rabbit preferences for certain species, e.g., avoiding hairy species such as Holcus lanatus or mosses (Zeevalking and Fresco 1977) or with higher water and protein content (Alves et al. 2006; Somers et al. 2008). Particularly, L. creticus seems to be very attractive for rabbits because it appeared even in unfavorable habitats such as the Retama understorey only when rabbits were excluded. In dune systems from the UK, rabbits reduced woody perennial cover, whereas rabbit exclusion increased graminoids (Millett and Edmonson 2013; Plassmann et al. 2009) but this outcome was not found in the present study likely due to the shorter experiment duration and the sampling season (spring), before the development of most annual graminoids (e.g., Vulpia spp., Bromus spp., and Lagurus ovatus, that occur in late spring and early summer).

The role of rabbits in vegetation structure and composition in coastal dunes may also depend on habitat type. On a large scale, most studies recognizing the potential role of rabbits on reducing shrub encroachment have been developed in dune grasslands from northern Europe, which are affected by higher nitrogen deposition rates (Erisman et al. 1998; Galloway et al. 2008) and rainfall than in southwestern Europe. Both conditions enhance plant growth, suggesting that the role of rabbits in coastal dune vegetation may be highly variable depending on the study region (including factors such as climate, nitrogen deposition, grazing intensity, or habitat type). Under rainfall limitations typical of the Mediterranean climate and lower nitrogen deposition rates, our results suggest that rabbits, even in lower densities than other studies (e.g., up to 45 rabbits/ha in Plassman et al. 2009), exert a strong top-down control, affecting the structure, composition and productivity of sand dune plant communities. At mesoscale (i.e., different dune communities), high rabbit densities have a differential effect between closed vegetation formations and open dunes (Isermann et al. 2010). In our study, rabbit grazing caused a significant decrease of both S and H´ either in sun-exposed dunes or the Retama understorey, with dominance of therophytes such as Carduus meonanthus and Echium gaditanum.

Our results suggest that there is no obvious rule of thumb for managing shrub encroachment in sand dunes. The origin of the encroachment (natural or human-mediated), the presence of threatened species, the climate type and the general conservation goal may recommend context-specific management solutions, not always aimed at dune ‘rejuvenation’ or ‘re-mobilization’ (Delgado-Fernandez et al. 2019). In the present study, the combination of Retama clearing and rabbit exclusion allowed the recovery of dune vegetation in the short term (two years), especially in sun-exposed areas. Our results also suggest that Thymus conservation may be improved by clearing dune areas affected by a high density of Retama. In contrast, rabbits exclusion may be counter-productive for Thymus, as the combined effect of Retama and dune vegetation could act synergistically to outcompete Thymus. Thus, long-term management of gray dunes affected by shrub encroachment and high rabbit density (habitat approach) would be the most effective solution for restoration of gray dunes as a priority habitat and their endangered flora. Rabbit exclusion may be needed to recover dune vegetation, particularly in areas heavily affected by shrub encroachment with a high rabbit density and not affected by nitrogen deposition. This recommendation is also supported by the role of rabbits in Retama dispersal by endozoochory (Dellafiore et al. 2006) and their impact on the abundance of flowering individuals (Mühl 1999). Thus, too many rabbits would reduce species diversity but few rabbits would allow shrubs to resprout and succession to develop faster. Therefore, long-term management (e.g., including repeated clearings) would be needed for shrubs with resprouting ablity.

The sandy soil and high broom cover found in the study area are preferred sites for warren construction (Dellafiore et al. 2008) but data on rabbit population dynamics are unknown. Then, we can assume that population may have followed a similar trend to neighboring areas. Wild, native rabbits were historically abundant and widespread on the Iberian Peninsula, however, the introduction of myxomatosis into the wild in the 1950s and further outbreak of rabbit hemorrhagic disease in 1989 caused a significant drop in their population (Virgós et al. 2007 and references therein). Moreover, the outbreak of a new rabbit hemorrhagic disease strain in 2012-2013 provoked an additional population decline (Carro et al. 2019). Despite the absence of hunting practices and some top predators such as the Iberian lynx in the study area, the density values reported in the study area (0.9 rabbit ha−1) remain within values reported in the Doñana National Park (50 km from the study area). These values are, however, far from densities reported before the first outbreak of the hemorrhagic disease (ca. 8.6 rabbit ha−1; Moreno et al. 2007). Given current population decline and the importance of rabbits as prey for many endangered predators, no massive elimination or exclusion of rabbits from this site is justified. However, rabbit exclusion from selected areas may be promoted to support fixed dunes recovery at least during early recovery stages of dune vegetation. On the contrary, Thymus conservation would not require rabbit exclusion but should prevent Retama from reaching a high cover. These results can serve as a basis for the management and restoration of coastal habitats affected by shrub encroachment.

References

AEMET (2019) http://www.aemet.es/es/serviciosclimaticos/datosclimatologicos/valoresclimatologicos?l=4642E&k=and. Accessed 9 July 2015

Alves J, Vingada J, Rodrigues P (2006) The wild rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus L.) diet on a sand dune area in Central Portugal: a contribution towards management. Wildl Biol Pract 2:63–71. https://doi.org/10.2461/wbp.2006.2.8

Avis AM (1995) An evaluation of the vegetation developed after artificially stabilizing south African coastal dunes with indigenous species. J Coast Conserv 1:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02835561

Bettink KA, Brown KL (2011) Determining best control methods for the National Environmental Alert List species, Retama raetam (Forssk.) Webb (white weeping broom) in Western Australia. Plant Prot Q 26:36–38

Bird TLF, Bouskila A, Groner E, Kutiel PB (2020) Can vegetation removal successfully restore coastal dune biodiversity? Appl Sci 10:2310. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10072310

Burggraaf-van Nierop YD, van der Meijden E (1984) The influence of rabbit scrapes on dune vegetation. Biol Conserv 30:133–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(84)90062-4

Carro F, Ortega M, Soriguer RC (2019) Is restocking a useful tool for increasing rabbit densities? Glob Ecol Conserv 17:e00560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00560

Castroviejo S (coord) (1986-2012) Flora iberica 1-8, 10-15, 17-18, 21. Real Jardín Botánico, CSIC, Madrid

Clarke KR, Warwick RM (2001) Change in marine communities: an approach to statistical analysis and interpretation. Plymouth Marine Laboratory. Primer software, Plymouth

Delgado-Fernandez I, Davidson-Arnott RGD, Hesp PA (2019) Is ‘re-mobilisation’ nature restoration or nature destruction? A commentary. J Coast Conserv 23:1093–1103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-019-00716-9

Dellafiore C, Muñoz S, Gallego-Fernández JB (2006) Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) as dispersers of Retama monosperma (L.) bois seeds in a coastal dune system. Ecoscience 13:5–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-009-9639-7

Dellafiore CM, Gallego JB, Muñoz-Vallés S (2008) Habitat use for warren building by European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in relation to landscape structure in a sand dune system. Acta Oecol 33:372–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2008.02.002

Erisman JW, Brydges T, Bull K, Gowling E, Grennfelt P, Nordberg L et al (1998) Summary statement. Environ Pollut 102:3e12

Esquivias MP, Zunzunegui M, Díaz-Barradas MC, Álvarez-Cansino L (2015) Competitive effect of a native-invasive species on a threatened shrub in a Mediterranean dune system. Oecologia 177:133–146

European Commission (2013) Interpretation manual of European Union habitats. EUR 28:1–144. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/legislation/habitatsdirective/docs/Int_Manual_EU28.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2021

Everard M, Jones L, Watts B (2010) Have we neglected the societal importance of sand dunes? An ecosystem services perspective. Aquat Conserv 20:476–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.1114

Fernández-de-Simon J, Díaz-Ruiz F, Cirilli F, Sánchez F, Villafuerte R, Delibes-Mateos M, Ferreras P (2011) Towards a standardized index of European rabbit abundance in Iberian Mediterranean habitats. Eur J Wild Res 57:1091–1100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-011-0524-z

Gallego-Fernández JB, Muñoz-Vallés S, Dellafiore C (2006) Flora and Vegetation on Nueva Umbría spit (Lepe, Huelva). Ayto, Lepe, p 134

Gallego-Fernández JB, Muñóz-Vallés S, Dellafiore CM (2015) Spatio-temporal patterns of colonization and expansion of Retama monosperma on developing coastal dunes. J Coast Conserv 19:577–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-015-0408-6

Galloway JN, Townsend AR, Erisman JW, Bekunda M, Cai Z, Freney JR et al (2008) Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Science 320:889e892

Gracia FJ, Muñoz JC (2009) 2130 Dunas costeras fijas con vegetación herbácea (dunas grises). En: VV.AA., Bases ecológicas preliminares para la conservación de los tipos de hábitat de interés comunitario en España. Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino, Madrid

Hammer Ø (2001) PAST PAleontological STatistics version 3.20. Reference manual. Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, Oslo

Houston J (2008) Management of Natura 2000 habitats. 2130 *Fixed coastal dunes with herbaceous vegetation (‘grey dunes’). Technical Report 2008 04/24. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/natura2000/management/habitats/pdf/2130_Fixed_coastal_dunes.pdf. Accessed 23 May 2021

Isermann M (2011) Patterns in species diversity during succession of coastal dunes. J Coast Res 27:661–671. https://doi.org/10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-09-00040.1

Isermann M, Diekmann M, Heemann S (2007) Effects of the expansion by Hippophaë rhamnoides on plant species richness in coastal dunes. Appl Veg Sci 10:33–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-109X.2007.tb00501.x

Isermann M, Köhler H, Mühl M (2010) Interactive effects of rabbit grazing and environmental factors on plant species-richness on dunes of Norderney. J Coast Conserv 14:103–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-009-0056-9

Kith-Tasara M (1946) El problema de las dunas del SO de España. Rev Montes 11:414–419

Kooijman AM, de Haan MWA (1995) Grazing as a measure against grass encroachment in Dutch dry dune grassland: effects on vegetation and soil. J Coast Conserv 1:127–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02905121

Kooijman AM, van Til M, Noordijk E, Remke E, Kalbitz K (2017) Nitrogen deposition and grass encroachment in calcareous and acidic Grey dunes (H2130) in NW-Europe. Biol Conserv 212:406–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.08.009

Kutiel P, Peled Y, Geffen E (2000) The effect of removing shrub cover on annual plants and small mammals in a coastal sand dune ecosystem. Biol Conserv 94:235–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(99)00172-X

Marchante H, Freitas H, Hoffmann JH (2011a) Post-clearing recovery of coastal dunes invaded by Acacia longifolia: is duration of invasion relevant for management success? J Appl Ecol 48:1295–1304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2011.02020.x

Marchante H, Freitas H, Hoffman JH (2011b) The potential role of seed banks in the recovery of dune ecosystems after removal of invasive plant species. Appl Veg Sci 14:107–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-109X.2010.01099.x

Martínez F, Montero G (2004) The Pinus pinea L. woodlands along the coast of South-Western Spain: data for a new geobotanical interpretation. Plant Ecol 175:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:VEGE.0000048087.73092.6a

Martínez ML, Psuty NP, Lubke RA (2004) A perspective on coastal dunes. In: Martínez ML, Psuty NP (eds) Coastal dunes. Ecology and conservation. Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 3–10

Martínez ML, Hesp PA, Gallego-Fernández JB (2013) Coastal dunes: human impact and need for restoration. In: Martínez ML, Gallego-Fernández JB, Hesp PA (eds) Restoration of coastal dunes. Springer, Berlin, pp 1–14

Millett J, Edmondson S (2013) The impact of 36 years of grazing management on vegetation dynamics in dune slacks. Journal of Applied Ecology 50(6):1367–1376. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12113

Moreno S, Beltrán JF, Cotilla I, Kufner MB, Laffite R, Jordan G, Ayala J, Quintero C, Jiménez A, Castro F, Cabezas S, Villafuerte R (2007) Long-term decline of the European wild rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in South-Western Spain. Wildl Res 34:652–658. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR06142

Moulton ABM, Hesp PA, Miot da Silva G, Bouchez C, Lavy M, Fernandez GB (2019) Changes in vegetation cover on the Younghusband peninsula transgressive dunefields (Australia) 1949–2017. Earth Surf Process 44:459–470. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4508

Mühl M (1999) The influence of rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus L.) on the vegetation of coastal sand dunes: preliminary results of exclosure experiments. Senck Marit 29:95–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03043130

Muñoz-Reinoso JC (2021) Effects of pine plantations on coastal gradients and vegetation zonation in SW Spain. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 251:107182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2021.107182

Muñoz-Vallés S, Cambrollé J (2015) The threat of native-invasive plant species to biodiversity conservation in coastal dunes. Ecol Eng 79:32–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2015.03.002

Muñoz-Vallés S, Gallego-Fernández JB, Dellafiore CM (2009) Estudio florístico de la Flecha litoral de El Rompido (Lepe, Huelva). Análisis y catálogo de la flora vascular de los sistemas de duna y marisma. Lagascalia 29:43–88

Muñoz-Vallés S, Gallego-Fernández JB, Dellafiore CM, Cambrollé J (2011) Effects on soil, microclimate and vegetation of the native-invasive Retama monosperma (L.) Boiss. in coastal dunes. Plant Ecol 212:169–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-010-9812-z

Muñoz-Vallés S, Gallego-Fernández JB, Cambrollé J (2013) The biological flora of coastal dunes and wetlands: Retama monosperma (L.) Boiss. J Coast Res 29:1101–1110. https://doi.org/10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-12-00013.1

Muñoz-Vallés S, Gallego-Fernández JB, Cambrollé J (2014) The role of the expansion of native-invasive plant species in coastal dunes: the case of Retama monosperma in SW Spain. Acta Oecol 54:82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2012.12.003

Muñoz-Vallés S, Cambrollé J, Gallego-Fernández JB (2015) Effect of soil characteristics on plant distribution in coastal ecosystems of SW Iberian Peninsula sand spits. Plant Ecol 216:1551–1570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-015-0537-x

Nordstrom KF, Lampe R, Vandemark LM (2000) Reestablishing naturally functioning dunes on developed coasts. Environ Manag 25:37–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002679910004

Palomares F (2001) Comparison of 3 methods to estimate rabbit abundance in a Mediterranean environment. Wildlife Soc B 29:578–585. https://doi.org/10.2307/3784183

Pickart AJ, Miller LM, Duebendorfer TE (1998) Yellow bush lupine invasion in northern California coastal dunes I. ecological impacts and manual restoration techniques. Restor Ecol 6:59–68. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-100x.1998.00618.x

Plassmann K, Edwards-Jones G, Laurence M, Jones M (2009) The effects of low levels of nitrogen deposition and grazing on dune grassland. Sci Total Environ 407:1391–1404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.10.012

Pye K (1983) Coastal dunes. Prog Phys Geogr 7:531–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/030913338300700403

Somers N, Bossuyt B, Hoffmann M, Lens L (2005) Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus L.) in coastal dune grasslands. In: Herrier J-L, Mees J, Salman A, Seys J, Van Nieuwenhuyse H, Dobbelaere I (eds). Proceedings ‘Dunes and Estuaries 2005’ – International Conference on Nature Restoration Practices in European Coastal Habitats, Koksijde, Belgium, 19-23 September 2005 VLIZ Special Publication 19, pp 661–663

Somers N, D’Haese B, Bossuyt B, Lens L, Hoffmann M (2008) Food quality affects diet preference of rabbits: experimental evidence. Belg J Zool 138:170–176

Talavera S (1999) Retama Raf. In: Talavera S et al (eds) Flora Ibérica, vol VII. CSIC, Madrid, pp 137–141

Valdés B, Talavera S, Fernández-Galiano E (1987) Flora Vascular de Andalucía Occidental, vol 3. Ketres editora S.A, Barcelona

Van der Maarel E (2003) Some remarks on the functions of European coastal ecosystems. Phytocoenologia 33:187–202. https://doi.org/10.1127/0340-269X/2003/0033-0187

Virgós E, Cabezas-Díaz S, Lozano J (2007) Is the wild rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) a threatened species in Spain? Sociological constraints in the conservation of species. Biodivers Conserv 16:3489–3504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-006-9054-5

Wouters B, Nijssen M, Geerling G et al (2012) The effects of shifting vegetation mosaics on habitat suitability for coastal dune fauna—a case study on sand lizards (Lacerta agilis). J Coast Conserv 16:89–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-011-0177-9

Zeevalking HJ, Fresco LFM (1977) Rabbit grazing and species diversity in a dune area. Vegetatio 35:193–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02097070

Zunzunegui M, Esquivias MP, Oppo F, Gallego-Fernández JB (2012) Interspecific competition and livestock disturbance control the spatial patterns of two coastal dune shrubs. Plant Soil 354:299–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-011-1066-6

Acknowledgements

This project has been financed with the Life Conhabit Andalucia project (LIFE13/NAT/ES/000586). The authors thank all field workers involved in the study.

Funding

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad de Cádiz/CBUA

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(ODT 32 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

García-de-Lomas, J., Fernández, L., Martín, I. et al. Management of coastal dunes affected by shrub encroachment: are rabbits an ally or an enemy of restoration?. J Coast Conserv 27, 8 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-023-00933-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-023-00933-3