Abstract

Dynamic capabilities (DCs) are a growing field of research within the scope of theoretical structures based on resource and strategic management. Given the demonstrated impact of DCs on company performance, it is important to study the effects of DCs on small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, this research evaluates the role of DCs during the pandemic and its impact on the performance levels of SMEs. Analysing the responses of 209 SMEs using a structural equations model, we report that DCs positively affect company performance both prior to and during the pandemic. However, we also verify that while prior to the pandemic companies placed greater emphasis on the search for new opportunities, following the onset of the pandemic the focus shifted to getting their products to the market. These results contribute to the literature on strategic management and the DC based approach during periods of turbulence and pandemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Between 2007 and 2013, the world experienced one of the most severe economic recessions since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The peripheral countries of Europe—Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain—ranked among those most severely affected. Sharp increases in unemployment, limited access to financing, and shrinkage in GDP rates were some of the perceivable consequences of the crisis (Mishkin, 2011; Papaoikonomou et al, 2012). Irrespective of the economic recovery that came about, with the difficulties inherent to each respective country, 2020 brought another major crisis, entirely unprecedented and unpredictable, namely the COVID-19 pandemic (Clark et al., 2020; Clauss et al, 2021; Breier et al, 2021).

The economic and social restrictions implemented to contain global crises inevitably caused major disruptions for companies. Within such an environment, the secret to untying this gordian knot arises from the development of dynamic capabilities (DCs) (Fainshmidt et al, 2017). Thus, deploying DCs serves to enhance the likelihood of organisational success within the currently prevailing context (Bailey and Breslin, 2020). Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) define DCs as the organisational and strategic routines by which companies obtain new configurations of resources in keeping with how markets emerge, collide, divide, evolve and die.

Hence, DCs affect company performance to the extent that it changes the package of resources, operational routines, and competences that, in turn, shape the firm’s economic performance (Helfat and Raubitschek, 2000; Zollo and Winter, 2002). Teece et al. (1997) defend how companies need to apply specific abilities to be able to effectively integrate, create, and reconfigure the internal and external competences necessary to their adaptation to rapidly changing environments. Various authors not only point out the need to study DCs but also to understand how these affect organisational performance in both internal and external environments (Wang and Ahmed, 2007; Ambrosini and Bowman, 2009; Helfat et al., 2009; Stoyanova, 2018; Grigoriou and Rothaermel, 2017; Zhang and Wu, 2017; Teece, 2018).

This indicates that DCs are essential when engaging in substantial and significant operations in globally competitive environments (Galbreath, 2005; Ahn and York, 2011). In this context, we propose that the performance of SMEs during the different phases of global crises (like COVID-19, for example) stems from the extent to which the SMEs are able to create, expand, or deliberately modify their resource bases (Helfat et al. 2007), hence, their DCs (Eikelenboom and Jong 2018). The distribution of DCs attains a heterogeneous incidence in companies given that they require high management and operating costs as well as high levels of managerial involvement (Ambrosini and Bowman, 2009). Therefore, the existing literature recognises the sweet-and-sour nature of social capital (Gao et al., 2017), proposing it as a facilitator and/or inhibitor of DCs depending on the surrounding external environment (Yeniaras et al., 2020).

Various researchers focus on the characteristics of the behaviours that enable SMEs to deal with diverse and different challenges as well as to improve their performance vis-à-vis large companies (Brouthers et al., 2009; Oura et al., 2016; Lobo et al., 2018; Nakos et al., 2018). However, instability arises in different ways in market environments, with the meaning and relevance of DCs varying in accordance to the nature of the respective prevailing instabilities. Our study approaches the relationship between DCs and SME performance within an unstable environment of crisis; in this case, the COVID-19 pandemic.

Therefore, this study addresses the following research question: How do DCs affect SME performance during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis?

Our research seeks to cast light on the ways in which DCs shape and influence the performance of SMEs during crises. However, we are aware that companies also differ in the way they deal with crises: some suffer considerably, others avoid the worst effects, while still others detect business opportunities. Thus, this study makes various contributions to the literature.

First, it contributes to the literature by testing for the direct effects of DCs on the performance of SMEs during a pandemic. Studying the ways in which companies adapt and implement their DCs fosters a better understanding of this multidimensional construct as well as the ongoing relationships among its respective different aggregating subdimensions. Economic downturns normally trigger profound industrial changes due to the fact that demand becomes so much more volatile. DCs may help companies get through these turbulent periods and, potentially, identify new business opportunities.

Secondly, it provides new lines for future research on the role of DCs in the performance of SMEs in times of crisis. Considering how the dynamism of companies is frequently assumed to be a defining condition for the capability-performance relationship (Peteraf et al., 2013), we demonstrate that DCs perform a fundamental role in the survival and competitiveness of firms facing adverse environments (Wang and Ahmed, 2007).

Furthermore, and thirdly, there is a lack of research studying the relationship between DCs and the performance of SMEs within the framework of global crises like a global pandemic (Makkonen et al., 2014; Fainshmidt et al, 2017).

Finally, this study also provides important implications for managers of SMEs. The conclusions convey how those SMEs that deploy/apply their DCs are able to ensure higher levels of performance in periods of crisis through their greater capacity to optimise their resource utilisation and capabilities in keeping with the appropriate deployment of their distinctive competences.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: in Sect. 2, we set out the theoretical underpinnings; Sect. 3 presents hypothesis development and conceptual model; Sect. 4 details the methodology, while Sect. 5 outlines the results and Sect. 6 provides the discussion of their implications, conclusions, limitations and future lines of research.

2 Theoretical underpinnings

As an offshoot of the resource based view (RBV), DCs emerged as an approach for understanding strategic changes (Teece et al., 1997), seeking to provide a structure for how companies develop and maintain competitive advantages in turbulent environments within the scope of identifying the determinants underlining long term success (Wilden et al., 2016; Alves & Galina, 2020).

Over the years, this definition has been revised and expanded, resulting in various conceptualisations. Furthermore, the descriptions of DCs frequently define them as company processes that consume resources, specifically the processes for integrating, reconfiguring, obtaining, and releasing resources to keep up with or even to create changes in the marketplace. Hence, perceptions of DCs may also encapsulate the organisational and strategic routines and processes through which companies leverage new configurations of their resources in keeping with how markets emerge, collide, divide, evolve, and die (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Ahmed et al. 2019).

Frequently, the operational implementation of DCs involves a set of distinctive groups of activities to explain how they function and thus to operationally apply them. According to Barrales-Molina et al. (2014), these groups generally divide up into the characteristics broadly accepted for such DC processes, such as reconfiguration, leveraging, learning, integration and coordination (Teece et al., 1997; Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000; Dabić, et al. 2019).

Thus, the DC approach appears to be one of the most popular in the field of strategic management (Arend, 2014). Teece et al. (1997) put forward the first comprehensive approach to DCs in the scientific literature. Subsequently, hundreds of articles and studies conceptually approach this topic (Di Stefano et al., 2014; Fernandes et al., 2017; Vlačić, et al. 2019).

The swift growth of the DCs literature includes a broad theoretical variety and considerable methodological scope, thus rendering it difficult, but not impossible, to maintain close control over the directions this research field takes. Various studies establish the intellectual foundations of the DC approach, not just summarising the definitions, but also discussing the respective components, determinants, obstacles, key empirical results, as well as identifying the conceptual shortcomings and the difficulties arising from its empirical applications (Zahra et al., 2006; Schreyögg and Kliesch-Eberl, 2007; Wang and Ahmed, 2007; Ambrosini and Bowman, 2009; Helfat and Peteraf, 2009; Barreto 2010; Fernandes et al., 2017; Hock-Doepgen, et al. 2021). An additional problem stems from the increasing proliferation of relevant publications. This is reflected in the considerable differences across the multiple perspectives regarding the perceptions and applications of DCs as well as on their varying influences on the development of strategic management. Arend (2014) concludes that this only somewhat vague or inconsistent theoretical justification places the DC approach at a disadvantage to other strategic management approaches. The same author is also critical of how this concept generally underutilises organisational theory and, more specifically, organisational change concepts like "absorption capacity", "organisational learning", and "change management".

In contrast, Helfat and Peteraf (2009) respond by arguing that the terminological and conceptual variety simply reflect the complexity of the phenomena under study and that it inherently requires multiple theoretical visions. These authors maintain that the continued exploration of fundamental research issues and the lack of empirical validation are characteristics of any field of research in its adolescent phase of development. Thus, the relevance of research focusing on DCs remains.

DCs enable prospecting for new opportunities in business environments and converting organisational resources into assets as well as tangible and intangible capacities (Easterby-Smith et al., 2009; Lucianetti, et al. 2018; Lövingsson, et al. 2000). The value creation processes explore these opportunities through the efficient and effective development of new products and services. Consequently, these dynamic resources reflect the capacities of organisations to create, extend, and intentionally modify their existing resource base. Thus, these resources facilitate change and renewal, ultimately fostering innovation that achieves a better adaptation to the surrounding environment (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000; Zollo and Winter, 2002; Winter, 2003; Zahra et al., 2006; Helfat et al., 2007; Dabić et al. 2013).

Hence, there are different conceptions regarding whether dynamic capabilities may inherently represent a source of increased performance (Baia et al., 2020; Wilden et al., 2016; Vrontis, et al. 2020). An initial phase in the approach to dynamic capabilities postulated a direct relationship between company DCs and their later performance (Makadok, 2001; Teece et al., 1997; Maley et al. 2020). Teece et al. (1997) share assumptions with the RBV that stipulates how resources are valuable, rare, difficult to imitate, and organisational (the VRIO model). Therefore, whenever DCs attain such characteristics, they may become a direct source of sustainable competitive advantages and, therefore, drivers of better performance (Barney, 1991; Ferreira and Fernandes, 2017; Singh et al. 2019).

Not every company experiences the consequences of a crisis in the same fashion (understandable, as companies are financially and intangibly differently endowed); companies also benefit differently from the government policies designed to recover from a crisis. Should we adopt the theories of cognitive behaviour and planning from the mid-1990s, then entrepreneurship becomes conceived as a process involving both perceptions of opportunities and the subsequent actions leading to the launching of new companies (Krueger, 1993; Busenitz et al., 2000).

During turbulent periods, sporadic shocks in the business cycle affect not only labour markets but also individuals launching new companies (Audretsch and Acs, 1994; Highfield and Smiley, 1987). Hence, theories on company life cycles maintain that economic shocks may produce ambiguous effects (Parker, 2011; Fairlie, 2013). Such shocks may enable individuals to detect and explore new entrepreneurial opportunities arising from the recessionary context or, alternatively, such uncertainties may dissuade individuals from searching for and detecting new business opportunities due to their innate pessimistic growth expectations (González-Pernía et al., 2018).

Correspondingly, the interrelationship between the organisation and its operational environment, in conjunction with the respective impact on company performance, make up central research themes and remain a focus of debate among management theoretical specialists (Makkonen et al., 2014; Santos et al., 2020).

This has led to the identification of certain processes and organisational capacities as more specific DCs, including dynamic marketing resources, dynamic management resources, specific supply chain resources, and alliances. The discussion on the nature of the relationship between the DCs and company performance emerged at roughly the same time as the concept itself. The question of how DCs really shape and affect company performance remains unknown, very much at the centre of debate (Pezeshkan et al., 2016). Furthermore, other authors express less confidence in any necessary and direct interrelationships (Barreto, 2010). Eisenhardt and Martin (2000), for example, reinforce the idea that DCs are, in fact, necessary, but insufficient, for generating competitive advantage. Within the framework of this vision, competitive advantage and long term performance do not depend on the DCs themselves but rather on their configurations and the effects of change (Barreto, 2010).

3 Hypothesis development and conceptual model

As of 2022, the world is in crisis, experiencing unprecedented economic disruption, because COVID-19 not just affects societies but also companies, especially if not handled appropriately (Pedersen et al., 2020; Cortez and Johnston, 2020; Obal and Gao, 2020; Zafari et al., 2020; Wenzel et al., 2021; Harms et al. 2021). Despite unprecedented levels of state support, estimates of the global economic contractions range from 6.1% in the United States, 9.1% in the Eurozone, and 7.2% in Latin America and the Caribbean to low growth of 0.5% in East Asia and the Pacific (World Bank, 2020). SMEs appear to be more vulnerable to external shocks due to their limited safety networks, access to credit, and social capital (Menguc and Dayan, 2020; Yeniaras et al. 2020). Furthermore, although a United Nations for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR, 2019) report identifies a growing number of global high risk events, the dynamic capacities literature has not noticeably focused on crisis management. Capacities involve the abilities of organisations to deploy their specific and idiosyncratic permutations of resources in conjunction with processes to modify, integrate, and renew their existing organisational skills and competences. Thus, DCs may represent a means of surviving this pandemic period (Kaur, 2020a).

Several authors use dimensions like sensing, conceptualizing, coproducing, orchestrating, scaling, and stretching to measure the impact of DC on company performance (Leifer et al., 2000; O'Connor, 2008; Jansen et al., 2015; Vahlne and Jonsson, 2017; Baden-Fuller and Teece, 2020).

3.1 Sensing

Sensing is related to the scope for producing a new range of products or services. This category breaks down into two (sub)capabilities related to supply and demand, corresponding to the orientation toward the client and the orientation toward the competition.

Jansen et al. (2015) intend to analyse the detection capacity of companies in this construct, trying to understand if companies systematically observe and assess customer needs as well as the actual use of their services or products. The key problem facing most organisations is not economic, in the sense of more or diverse resources and capabilities, or even more loyal customers; rather, it is cognitive, perhaps even emotional (Porac, 1989).

The cognitive side of competitive dynamics is completely omitted from traditional neoclassical economics, also given scant attention in the resource-based view. It is the capacity of established firms (and new ones too) to see possibilities that others have not seen and the capacity to inspire and mobilise both employees and strategic partners to commit resources in an effort to exploit the perceived opportunities that are the core of competitive dynamics (Baden-Fuller and Teece, 2020).

H1

Sensing (dynamic capability) has a positive effect on performance.

3.2 Conceptualizing

Within DCs, conceptualizing is the essential capability to select and develop an idea. In this construct, Jansen et al. (2015) intend to assess the greater or lesser ease of conceptualising their services or products. They assess whether companies are innovative in presenting or experimenting with new concepts or ideas for new service or product concepts. The innovation literature explores radical innovation (Leifer et al., 2000), breakthrough innovation (O'Connor, 2008), discontinuous innovation (Kaplan et al., 2003), and disruptive innovation (Christensen, 1997), offering both theoretical and practical pointers for transforming strategies in large corporations to advance technologies and create new markets. Kodama (2017) argues that the ability to conceptualize and develop new ideas, turning them into innovations, is a dynamic capability crucial for the performance of companies.

H2

Conceptualizing (dynamic capability) has a positive effect on performance.

3.3 Coproducing and orchestrating

The coproducing and orchestrating construct is interrelated with the partnerships established to retail the new products/services. With this construct, Jansen et al. (2015) want to assess the firm's ability to maintain partnerships and initiate new ones; they also want to check whether cooperation with other organizations allows them to improve or introduce new services or products. Thus, this identifies if they have an organization that can help them coordinate innovation activities that involve multiple parties.

To build dynamic capability for coping with global marketing turbulence, the companies must flexibly reconfigure their organizational structure, hiring employees with a wide variety of skills. These employees then, based on the company’s vision and goals, cooperate with upstream companies and downstream partners to seek compatible goals that promote flexible strategic actions (Vahlne and Jonsson, 2017). Organizational goals that guide strategies and activities provide the basis of goal interdependence that affects the interaction patterns between organizations and, in turn, determines companies’ outcomes, including business development, organizational competence, and performance (Wong et al., 2012; Yang and Gan, 2021).

H3

Coproducing and orchestrating (dynamic capabilities) have a positive effect on performance.

3.4 Scaling and stretching

Scaling and stretching incorporate those efforts required to get a new product/service to the market. With this construct, authors intend that in the case of a successful product or service, companies will be able to extend it to the entire organization (Jansen et al., 2015). A spearhead for communicating, embodying, and orchestrating new market values (Conejo and Wooliscroft 2015), brands can influence and reflect not just societal values (Berthon and Pitt 2018) but also sociocultural and political views (Vredenburg et al. 2020). Brands also can address cultural anxieties and contradictions (Kadirov et al., 2016), which may entail institutional change for social issues unrelated to direct business operations (Kemper and Ballantine 2019).

Although brands may participate in efforts toward the betterment of society due to a perceived responsibility to do so (Moorman 2020), an understanding of how branding may orchestrate social change needs greater attention (Conejo and Wooliscroft 2015; Spry et al., 2021). Realizing whether branding strategies are considered in developing new products or services as well as the existence of a marketing plan is also an object of analysis in this dimension. Finally, the authors intend to understand if companies are actively involved in promoting their new products or services (Jansen et al., 2015).

H4

Scaling and stretching (dynamic capabilities) have a positive effect on performance.

DCs may play crucial roles during the crisis, especially for SMEs that are particularly exposed. Global crisis are difficult for SMEs (Eggers, 2020), in particular, COVID-19. Crises may bring opportunities within the scope of pre-crisis normality, the occurrence of the emergency, the post-crisis period, and the post-crisis normality (Pedersen et al. 2020; Wendt et al. 2021). But, taking into account the limitations of SMEs (Freeman et al., 1983), they may not always hold the resources necessary to identify market opportunities and threats, whether for exploring or for neutralising (Ambrosini and Bowman, 2009; Hoskisson et al., 2011).

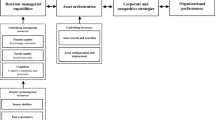

In Fig. 1, we set out our conceptual model.

4 Methodology

4.1 Data and sample

To examine the conceptual research model and test the respective relationships, we drafted a questionnaire as the means of data collection. This questionnaire contained two sections, the first for characterising the companies and the second containing measurement scales for items depicting the attitudes and opinions of the respondents about the DCs of their companies. To provide an empirical context within which a market oriented economy renders DCs relevant for organisational success, the survey targeted Portuguese SMEs.

This study highlights the benefits of applying partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) to empirical research on strategic management, which commonly requires the modelling of latent constructs, in this case the DCs, and testing for complex relationships in small samples (Hair et al., 2019; Hulland, 1999). Furthermore, our study demonstrates the worth of applying PLS-SEM to the model’s latent, second order construct (Sarstedt et al., 2019). In addition, we present a procedure for applying PLS-SEM to analyse the effects before and during the pandemic as well as the stability of the construct with respect to the DCs.

Data collection took place over two stages. First, we carried out a pilot study with ten SMEs selected randomly from the database supplied by the Agency for Investment and External Trade of Portugal (AICEP).Footnote 1 We contacted the managers by means of telephone. Based on their answers and the subsequent interviews with the pre-test participants, we made certain small changes to the questionnaire. The responses of the companies taking part in the pilot study were not subject to inclusion in the final sample.

In the second phase, we distributed the questionnaires via e-mail to 500 SMEs selected randomly from the database but representative in terms of their geographic location, company size, and sectors of activity. Responses to this questionnaire came from senior or intermediate managers with responsibilities for company strategic activities. The final sample contained a total 209 SMEs, corresponding to a response rate of 41.8%. The survey was answered during the months of September and October 2020, before the second wave of COVID-19 in Portugal.

We examined the data for non-response bias and compared the characteristics of early and late questionnaire respondents. The results of this comparison demonstrate that non-response bias does not represent a threat to either the viability of the results obtained or their respective interpretation. In terms of characterising the companies, we gathered variables relating to their business economic activities, the location of their headquarters, company size, financial performance in 2019, and the variations in the expected financial performance for 2020.

Table 1 details the sample company characteristics.

4.2 Measurement

To measure company DCs, we applied the 18-item scale proposed by Janssen et al. (2015). These items spanned the dimensions of Sensing (six items), Conceptualizing (four items), Coproducing and orchestrating (three items), as well as Scaling and stretching (five items). The data collection instrument asked managers to respond according to their level of agreement using a seven point Likert scale (1 = total disagreement; 7 = total agreement), with the statements about their DCs before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Table 3 reports on the items comprising the DC constructs.

To measure performance, we used the variable related to turnover (euros) in 2019 (< 100,000; 100,000–500,000; 500,000–1,000,000; 1,000,000–2,000,000; 2,000,000–10,000,000; 10,000,000–50,000,000; > 50,000,000), which is an objective indicator. The variation in performance was measured based on the increase or decrease in turnover (%) in 2020 compared to 2019 (Decrease more than 75%; Decrease between 50 and 75%; Decrease between 25 and 50%; Decrease less than 25%; Maintain; Increase less than 25%; Increase between 25 and 50%; Increase between 50 and 75%; Increase more than 75%); this variable represents the perception of the responding manager in September/October 2020.

4.3 Statistical methods

The estimation approach uses Partial Least Squares (PLS-SEM), a method widely used in the field of business sciences and deployed with the objective of estimating models such that the squared deviation between the values observed and those estimated are the minimum (Dijkstra and Henseler, 2015; Hair et al., 2011, 2012a, b, 2014; Hulland, 1999).

The application of PLS-SEM as an alternative to covariance based SEMs (CB-SEM) arises from the items not following normal distribution, an assumption for the data distribution in CB-SEM, and alongside some variables included in the model being ordinal qualitative variables (Hair et al., 2019, 2020).

To confirm the factorial structure of the instrument, there is a need to examine the reliability and validity of the indicators deployed to represent and measure the theoretical concepts (Hair et al., 2019, 2020; Sarstedt et al., 2019).

As there is no single test that best evaluates the reliability and validity of the constructs, various measures serve to evaluate the quality of the adjustment. Composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s Alpha (Alpha) serve to estimate the internal consistency and reliability of the reflexive items of the factor or construct (CR and Alpha ≥ 0.7). As regards the validity of the instrument, there are three measures for application: (1) factorial validity; (2) convergent validity; and (3) discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2019, 2020; Sarstedt et al., 2019). Factorial validity derives from evaluating the standardised factorial weightings of each item in relation to the construct (Hair et al., 2010). In turn, the evaluation of convergent validity takes place through the average variance extracted (AVE) of the construct (Hair et al., 2010) while analysis of discriminant validity follows the criteria stipulated by Fornell and Larcker (1981).

Table 2 contains a summary of the criteria applied to analyse the validity and reliability of the data collection instrument.

As there are no measurements for the overall appropriate level of adjustment reliability for PLS-SEM, as there are for CB-SEM, the evaluation of PLS-SEM incorporates analysis of the determinant coefficient values (R2 greater than 25%) for the endogenous constructs and the standardised residual median squared root value (SRMR below 0.08) (Bagozzi and Yi, 2011; Hair et al., 2011). In order to calculate the structural models and to determine the t statistics and their respective statistical significance, we deployed the bootstrapping procedure (with a total of 1000 bootstrap samples and 209 bootstrap cases).

With the data available in a panel format, the evolution model defined by Roemer (2016) provides an appropriate modelling type. With panel data, the alterations in the dynamic capabilities may be subject to analysis over time. For the interpretation of the transition effects, we apply auto-regressive effects with these interrelating with the stability of a point in time construct (before the COVID-19 pandemic) toward the next point in time (during the COVID-19 pandemic). A significant effect means that the construct calculation remains stable over the course of time (Little and Card, 2013).

All of the calculations use SmartPLS version 3.3.2 (Ringle et al., 2015) and IBM SPSS version 27.0 for Windows (IBM Corporation, New York, USA) software programs.

5 Results

5.1 Construct validity and reliability

For all the constructs, Cronbach’s Alpha and the factorial weightings report values above the levels required: 0.7 and 0.5, respectively. The composite reliability is also above the necessary limit of 0.7. For all the constructs, with the exception of that for second order dynamic resources, the AVE result is also above the limit of 0.5. In order to test whether the constructs mutually differ to a sufficient extent, we ascertained the discriminant validity in accordance with the Fornell and Larcker criteria (1981), which require the AVE of a construct to be greater than the squared value of its greatest correlation with any construct.

Table 3 displays the results returned by the descriptive statistics, the reliability and validity of the latent constructs. This observes how the different constructs (Sensing, Conceptualizing, Coproducing and orchestrating, and Scaling and stretching) encapsulating the DCs report high levels of reliability in conjunction with factorial validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Hence, we may deem the results of the DC measurement instrument as valid and reliable for application.

5.2 Structural model

To validate the study hypotheses, we apply the SEM model, which also enables the evaluation of whether the DC factorial structure underwent any alterations (Fig. 2).

The standardised structural equation estimates resulted from the PLS method based on the second order constructs. The structural model displays a good quality of adjustment (SRMR = 0.068; R2 of Performance = 59.2%; R2 of Performance Variation = 31.6%). The standardised solution estimated serves as the basis for interpreting the results of the structural relationships and as summarised in Table 3.

As set out in Table 4, the DC dimensions existing prior to the pandemic report a statistically significant impact on those dimensions during the pandemic. These results convey how the conceptual structure of SME DCs did not undergo any alterations throughout this period of COVID-19 pandemic.

Our results highlight the importance of DC both before and during the pandemic. We highlight some important differences. Regarding H1: Sensing (dynamic capability) has a positive effect on performance, we find that this dimension has a positive effect before the pandemic (β = 0.251; p < 0.043), but it loses significance during the pandemic (β = 0.205; p < 0.058). These results lead us to consider that during troubled periods companies are more focused on putting products on the market than on the possibility of producing something new.

Concerning H2: Conceptualizing (dynamic capability) has a positive effect on performance, our results show that this dimension plays an important role before (β = 0.322; p < 0.009) and during the pandemic (β = 0.300; p < 0.014). In this way, the importance of conceptualizing new ideas in products or services is present, both in relatively quiet times and in troubled times, in the performance of companies.

As for H3: Coproducing and orchestrating (dynamic capabilities) have a positive effect on performance. This dimension, which is related to efforts to bring a new product or service to market, significantly affects performance during the pandemic (β = 0.498; p < 0.000), but not before the pandemic. These results lead us to consider that during troubled periods companies are more focused on putting products on the market than on the possibility of producing something new.

Finally, for H4: Scaling and stretching (dynamic capabilities) have a positive effect on performance: it has a positive effect both before (β = 0.249; p < 0.049) and during (β = 0.224; p < 0.007) the pandemic. These results show us that when organizations are successful in a product or service, they extend it to the entire organization. This is especially important in times of greater volatility.

5.3 Dynamic capabilities and performance according to firm size and economic activity

To identify the relationships between some control variables and responses related with DCs and firm performance, we compute descriptive statistics, which are presented in Tables 5 and 6. Regarding DCs, there are no notable differences between industry and services regarding the mean scores of the different constructs. As for firm size, companies with at least 10 employees present higher mean scores of the different constructs than do micro-firms (Table 5).

As for the perception of performance variation, in industry 57.8% of respondents perceived a reduction in turnover in 2020, with this proportion being 51.4% in services, 56.5% in micro-firms, and 52.4% in companies with at least 10 employees (Table 6).

6 Discussion and conclusion

The ways in which companies are able to maintain their levels of performance and innovation during a global crisis, specifically throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, is a question requiring the application of new concepts and structures that may differ from more traditional concepts. While theoretical research on the impact of the dynamic capabilities of companies on performance and innovation provide alternative conceptual structures, empirical research returns only dispersed and frequently difficult to compare results (Beliaeva et al, 2020; Kraus et al, 2020; Wenzel et al, 2021).

Our research contributes to overcoming this shortcoming in the literature by providing a basis for empirically measuring the strength of the DC effect on assisting SMEs to maintain their performance. While the pandemic difficulties are generalised in scope, by developing their DCs, companies gain a greater likelihood of being able to cope with their impact (Obal and Gao, 2020; Zafari et al., 2020). Thus, we demonstrate how the means for untying this gordian knot stem precisely from the DCs (Fainshmidt et al, 2017). These greater competences boost the likelihood of organisational success in the current period (Bailey and Breslin, 2020). This emerges through the relevance of the Conceptualizing construct conveying the essential capabilities of companies to select and develop an idea, and the Coproducing and Orchestrating construct that encapsulates efforts to get new products to market; these jointly enable companies to maintain their performance levels.

Therefore, DCs represent the abilities of organisations to apply their idiosyncratic permutations of resources effectively as processes for modifying, integrating, and renewing their existing organisational competences (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000; Teece et al., 1997). Organisations worldwide need to undergo a paradigm shift, not only to survive the current crisis but also to prosper in a post-Covid-19 recessionary environment—a totally new world in which clients concerned with costs continually seek greater value for less expenditure (Pedersen et al., 2020; Cortez and Johnston, 2020). Within this framework, we verify the changes that companies are able to process in terms of their dynamic capabilities. If, before the pandemic broke out, Sensing constituted a priority, thus the search for opportunities to come up with new products and services with a client oriented focus, when companies are in the “eye of the hurricane”, they engage in a transition to Coproducing and orchestrating. This becomes possible in keeping with how companies have already been able to develop, and continue to maintain, their focus on Conceptualizing.

The coronavirus pandemic wreaked havoc on the business environment, not only in terms of the availability of certain resources but also due to the general scarcity of many other resources. Even in such times, we still must note that having less does not necessarily mean doing less. In situations when organisations need flexibility in their existing resources, members of staff face the challenge of moving on from a shortage focused mentality in order to take advantage of the resources existing to thereby guarantee the optimal application of the organisation’s respective resources (Zafari et al., 2020).

In this context, the development of creative attitudes to overcome the prevailing challenges may drive industry toward untying this gordian knot (Conceptualizing and Coproducing and orchestrating). Indeed, in times of frugality, organisations compensate for the lack of resources by turning strongly toward their internal and external stocks of knowledge as well as their respective learning capacities (Hossain, 2021; Kaur, 2020b). During the Covid-19 pandemic, these problems essentially all deepen, hence the utilisation of DCs emerged as a solution to the pandemic while simultaneously equipping organisations with the capabilities of ensuring instantaneous responses to the ongoing dynamism in the surrounding environment (Yeniaras et al. 2020).

In fact, the DC may flourish as it remains necessary to be at the top, even during the pandemic. This ambidextrous approach contains the scope for producing synergies, thereby methodically transforming them into a magic formula that grants frugal organisations some advantages. Such advantages may help organisations not only coping with the COVID-19 crisis but also with building a COVID-19 legacy deeply sustained by the dynamic resources based on internal knowledge (Eggers, 2020; Meyer et al, 2022).

Our research brings has important implications for research into dynamic capabilities. The first relates to strategic management theory. In approaching the resilience of companies through recourse to their DCs in periods of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Obal and Gao, 2020; Zafari et al., 2020), we demonstrate the importance of this tool to company performance and their overcoming such adverse periods.

Furthermore, because we analyse the impact of DC before and during the pandemic, our results may facilitate understanding the impacts of pre-crisis DCs and the consequences of their application during the pandemic. According to our results, we may state that the strong management of these assets, especially of capacities, may represent the secret to the survival of organisations during such turbulent periods. The environments surrounding dynamic tasks lead companies to develop the capabilities essential for dealing with change even though preparations for one type of change may not necessarily generalize to those required for other types.

According to Linnenluecke et al. (2011), organisations that are highly optimised to deal with certain surrounding conditions are more prone to experience a lack of resilience against unexpected shocks. Hence, we provide new conceptual insights into the resilience of SMEs, highlighting the importance of DCs for their performance.

Secondly, we generate new knowledge for the dynamic resource vision. The evolutionary nature and DC dependent approach, as management capability assets, may make them less effective whenever SMEs encounter unforeseen events (Schilke, 2014), which managers have difficulty in identifying and creating packages of productive resources (Ambrosini and Bowman, 2009). DCs do not always represent the most appropriate means of change even if there is a significant need for resource configuration.

Our research demonstrates that the surrounding environment within which DCs evolve may determine the effectiveness of their approaches to less typical types of change, like a global economic recession triggered by a global public health issue. Thus, DCs stand out as potential proxies for resilience. These capabilities may contribute to the resilience of SMEs, depending on the context prevailing around these capabilities. Thus, we may infer how the general efficiency and effectiveness of DCs is influence by the ways in which SMEs interact with their surrounding environments over the course of time. This process deserves far greater attention within the framework of DC research to better understand the performance results of such capabilities.

Finally, we contribute to research on the fungibility of resources. Within this scope, while organisations may boost their fungibility, thereby gaining a greater range of strategic options, fungibility inherently depends on the context just as resilience may take on various forms, holding different requirements in different environments. In environments displaying a shortage of resources, for example, earlier research indicates that resilience to crises may deepen through the development of close networks and personalised strategies.

In face of the COVID-19 pandemic and its serious health consequences, manifesting in high death rates and high risk of infection, the authorities stipulated strict isolation and social distancing measures, negatively impacting economic activities and, consequently, on the financial positions of companies (Ataguba and Ataguba, 2020).

In this context, one hope arises from developing DCs (Fainshmidt et al., 2017); and so doing, boosting the likelihood of company survival and success (Bailey and Breslin, 2020). In keeping with the set research question—What role do DCs play in SMEs performance during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis?—we note that DCs effectively perform a fundamental role in the SME response to the emergency circumstances of the pandemic. However, and through the application of the constructs incorporated into the research model, we may verify that not all DCs contain the same influence before and during the pandemic. In this pandemic period, companies focus greater efforts on getting their products to the market than in the eventual production of something new. Company DCs associated with decision-making that involve a combination of abilities, processes, and routines foster growth in organisational knowledge, thus enabling an appropriate response to the crisis situation.

Within this framework, our study further demonstrates how DCs facilitate company performance during periods of crisis. Through developing their DCs, companies gain a greater probability of overcoming their impacts through deploying higher levels of competences and skills. These distinctive capacities endow the organisation with a greater capability to optimise the application of its resources and capacities, not just guaranteeing greater efficiency in the development of new processes but also for optimising those processes that require adaptation to the new contexts emerging in the surrounding environment.

Our research displays certain limitations that may themselves provide fruitful avenues for future research. Our research took place during a crisis, focusing on the implications of the effects of DCs on company performance standards. In periods of great turbulence, the results may be subject to extreme volatility. Our sample contained only SMEs: examination of a different company sample, for example made up of born global firms, which can emerge from within such crisis contexts, may provide different and additional perceptions. Another issue can be identified in that DCs and performance variation are self-report metrics.

There are also recommendations for other future lines of research, targeting SMEs with operations ongoing in international markets, their network capability, and establishing terms of comparison for their performance levels in periods of pandemic crisis against other SMEs without such international operations.

Despite the proposition of DCs as able to generate sustainable competitive advantages (Helfat and Martin, 2014; Teece, 2007), the study of this may require greater nuance, especially when approaching contexts of unforeseen change, like crises. There is also a need for research to identify contingencies within the ongoing dynamic relationship between resources and performance so as to advance toward the construction of a more robust and complete theory regarding the role of DCs in management.

Notes

This database contains the respective details of 15,000 SMEs.

References

Ahmed SS, Guozhu J, Mubarik S, Khan M, Khan E (2019) Intellectual capital and business performance: the role of dimensions of absorptive capacity. J Intell Cap. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-11-2018-0199

Ahn MJ, York AS (2011) Resource-based and institution-based approaches to biotechnology industry development in Malaysia. Asia Pac J Manag 28(2):257–275

Alves MF, Galina SV (2020) Measuring dynamic absorptive capacity in national innovation surveys. Manag Decis. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-05-2019-0560

Ambrosini V, Bowman C (2009) What are dynamic capabilities and are they a useful construct in strategic management? Int J Manag Rev 11(1):29–49

Arend RJ (2014) Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: How firm age and size affect the “capability enhancement-SME performance relationship. Small Bus Econ 42(1):33–57

Ataguba OA, Ataguba JE (2020) Social determinants of health: the role of effective communication in the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. Glob Health Action 13(1):1788263

Audretsch DB, Acs ZJ (1994) New-firm startups, technology, and macroeconomic fluctuations. Small Bus Econ 6(6):439–449

Baden-Fuller C, Teece DJ (2020) Market sensing, dynamic capability, and competitive dynamics. Ind Mark Manag 89:105–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.1

Bagozzi RP, Yi Y (2011) Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci 40(1):8–34

Baia E, Ferreira J, Rodrigues R (2020) Value and rareness of resources and capabilities as sources of competitive advantage and superior performance. Knowl Manag Res Pract 18(3):249–262

Bailey K, Breslin D (2020) The COVID-19 pandemic: What can we learn from past research inorganizations and management? Int J Manag Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12237

Barney J (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manag 17(1):99–120

Barrales-Molina V, Martínez-López FJ, Gázquez-Abad JC (2014) Dynamic marketing capabilities: toward an integrative framework. Int J Manag Rev 16(4):397–416

Barreto I (2010) Dynamic Capabilities: A review of past research and an agenda for the future. J Manag 36(1):256–280

Beliaeva T, Shirokova G, Wales W, Gafforova E (2020) Benefiting from economic crisis? Strategic orientation effects, trade-offs, and configurations with resource availability on SME performance. Int Entrep Manag J 16(1):165–194

Berthon PR, Pitt LF (2018) Brands, truthiness and post-fact: managing brands in a post-rational world. J Macromark 38(2):218–227

Breier M, Kallmuenzer A, Clauss T, Gast J, Kraus S, Tiberius V (2021) The role of business model innovation in the hospitality industry during the COVID-19 crisis. Int J Hosp Manag 92:102723

Brouthers L, Nakos G, Hadjimarcou J, Brouthers KD (2009) Key factors for successful export performance for small firms. J Int Mark 17(3):21–38

Busenitz L, Gómez C, Spencer J (2000) Country institutional profiles: unlocking entrepreneurial phenomena. Acad Manag J 43(5):994–1003

Christensen CM (1997) The innovator’s dilemma: when new technologiescause great firms to fail. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA

Clark C, Davila A, Regis M, Kraus S (2020) Predictors of COVID-19 voluntary compliance behaviors: an international investigation. Global Trans 2:76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glt.2020.06.003

Clauss T, Breier M, Kraus S, Durst S, Mahto RV (2021) Temporary business model innovation-SMEs’ innovation response to the Covid-19 crisis. R&D Manag. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12498

Conejo F, Wooliscroft B (2015) Brands defined as semiotic marketing systems. J Macromark 35(3):287–301

Cortez RM, Johnston WJ (2020) The Coronavirus crisis in B2B settings: Crisis uniqueness and managerial implications based on social exchange theory. Ind Mark Manage 88:125–135

Dabić M, Potocan V, Nedelko Z, Morgan TR (2013) Exploring the use of 25 leading business practices in transitioning market supply chains. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 43(10):833–851

Dabić M, Vlačić E, Ramanathan U, Egri CP (2019) Evolving absorptive capacity: the mediating role of systematic knowledge management. IEEE Trans Eng Manage 67(3):783–793

Di Stefano G, Peteraf M, Verona G (2014) The organizational drivetrain: a road to integration of dynamic capabilities research. Acad Manag Perspect 28(4):307–327

Dijkstra TK, Henseler J (2015) Consistent and asymptotically normal PLS estimators for linear structural equations. Comput Stat Data Anal 81:10–23

Easterby-Smith M, Lyles MA, Peteraf MA (2009) Dynamic capabilities: current debates and future directions. Br J Manag 20:S1–S8

Eggers F (2020) Masters of disasters? Challenges and opportunities for SMEs in times of crisis. J Bus Res 116:199–208

Winter SG (2003) Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strateg Manag J 24(10):991–995

Eikelenboom M, De Jong G (2018) The impact of dynamic capabilities on SME sustainable performance. Academy of Management Proceedings (1) 11482. Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management

Eisenhardt K, Martin J (2000) Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg Manag J 21:1105–1121

Fainshmidt S, Nairb A, Mallon M (2017) MNE performance during a crisis: an evolutionary perspective on the role of dynamic managerial capabilities and industry context. Int Bus Rev 26:1088–1099

Fairlie RW (2013) Entrepreneurship, economic conditions, and the great recession. J Econ Manag Strateg 22(2):207–231

Fernandes C, Ferreira J, Raposo ML, Estevão C, Peris-Ortiz MR (2017) The dynamic capabilities perspective of strategic management: a co-citation analysis. Scientometrics 112(1):529–555

Ferreira J, Fernandes C (2017) Resources and capabilities’ effects on firm performance: What are they? J Knowl Manag 21(5):1202–1217

Wong A, Fang SS, Tjosvold D (2012) Developing business trust in government through resource exchange in China. Asia Pac J Manag 29(4):1027–1043

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50

Freeman J, Carroll GR, Hannan MT (1983) The liability of newness: age dependence in organizational death rates. Am Sociol Rev, 692–710

Galbreath J (2005) Which resources matter the most to firm success? An exploratory study of resource-based theory. Technovation 25(9):979–987

Gao Y, Shu C, Jiang X, Gao S, Page AL (2017) Managerial ties and product innovation: the moderating roles of macro-and micro-institutional environments. Long Range Plan 50(2):168–183

González-Pernía JL, Guerrero M, Jung A-L (2018) Economic recession shake-out and entrepreneurship: Evidence from Spain. BRQ Bus Res Q 21(3):153–167

Grigoriou K, Rothaermel FT (2017) Organizing for knowledge generation: internal knowledge networks and the contingent effect of external knowledge sourcing. Strateg Manag J 38(2):395–414

Hair JF, Black B, Babin B, Anderson RE, Tatham RL (2010) Multivariate data analysis, 7th edn. Pearson Prentice Hall, London, United Kingdom

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2011) PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J Mark Theor Pract 19(2):139–152

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2012a) Partial least squares: the better approach to structural equation modeling? Long Range Plan 45(2012):312–319

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Mena J (2012b) An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J Acad Mark Sci 40:414–433

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Hopkins L, Kuppelwieser VG (2014) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur Bus Rev 26(2):106–121

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24

Hair JF, Howard MC, Nitzl C (2020) Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J Bus Res 109:101–110

Harms R, Alfert C, Cheng C-F, Kraus S (2021) Effectuation and causation configurations for business model innovation: addressing COVID-19 in the gastronomy industry. Int J Hosp Manag 95:102896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102896

Helfat CE, Peteraf MA (2009) Understanding dynamic capabilities: progress along a developmental path. Strateg Organ 7(1):91–102

Helfat CE, Raubitschek RS (2000) Product sequencing: Co-evolution of knowledge, capabilities and products. Strateg Manag J 21(10/11):961–979

Helfat CE, Finkelstein S, Mitchell W, Peteraf MA, Singh H, Teece DJ, Winter SG (2007) Dynamic capabilities: understanding strategic change in organizations. Blackwell, Malden, MA

Helfat CE, Finkelstein S, Mitchell W, Peteraf MA, Singh H, Teece DJ, Winter SG (2009) Dynamic capabilities: foundations. In: Helfat CE, Finkelstein S, Mitchell W, Peteraf M, Singh H, Teece D, Winter SG (eds) Dynamic capabilities: understanding strategic change in organizations. Wiley, New York, pp 1–18

Highfield R, Smiley R (1987) New business starts and economic activity: an empirical investigation. Int J Ind Organ 5(1):51–66

Hock-Doepgen M, Clauss T, Kraus S, Cheng CF (2021) Knowledge management capabilities and organizational risk-taking for business model innovation in SMEs. J Bus Res 130:683–697

Hoskisson RE, Covin J, Volberda HW, Johnson RA (2011) Revitalizing entrepreneurship: the search for new research opportunities. J Manag Stud 48(6):1141–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00997.x

Hossain M (2021) Frugal innovation: unnveiling the unconfortable reality. Technol Soc 67:101759

Hulland J (1999) Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: a review of four recent studies. Strateg Manag J 20:195–204

Janssen MJ, Castaldi C, Alexiev A (2015) Dynamic capabilities for service innovation: conceptualization and measurement. R&D Manag 46(4):797–811

World Bank (2020) Global economic prospects. Pandemic Recess Global Econ Crisis. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1553-9

Yang L, Gan C (2021) Cooperative goals and dynamic capability: the mediating role of strategic flexibility and the moderating role of human resource flexibility. J Bus Ind Mark 36(5):782–795

Kadirov D, Varey RJ, Wolfenden S (2016) Investigating chrematistics in marketing systems: a research framework. J Macromark 36(1):54–67

Kaplan S, Murray F, Henderson R (2003) Discontinuities and seniormanagement: assessing the role of recognition in pharmaceutical firmresponse to biotechnology. Ind Corp Chang 12(4):203–233

Kaur V (2020a).Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities: the panacea for pandemic. California Management Review, Insight Note, 28

Kaur V (2020b) Frugal innovation: knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and pandemic response. California Management Review, Insight Note, 24

Kemper JA, Ballantine PW (2019) Targeting the structural environment at multiple social levels for systemic change. J Soc Mark 10(1):38–53

Kodama M (2017) Developing strategic innovation in large corporations-the dynamic capability view of the firm. Knowl Process Manag 24(4):221–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.1554

Kraus S, Clauss T, Breier M, Gast J, Zardini A, Tiberius V (2020) The economics of COVID-19: initial empirical evidence on how family firms in five European countries cope with the corona crisis. Int J Entrep Behav Res 26(5):1067–1092

Krueger N (1993) The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrep Theor Pract 18(1):5–21

Leifer R, McDermott M, O’Connor C, Peters S, Rice M, Veryzer W (2000) Radical innovation: how mature companies can outsmart upstarts. Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge, MA

Linnenluecke MK, Griffiths A, Winn M (2011) Extreme weather events and the critical importance of anticipatory adaptation and organizational resilience in responding to impacts. Bus Strateg Environ 21(1):17–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.708

Little TD, Card NA (2013) Longitudinal structural equation modeling. The Guilford Press, New York

Lobo C, Fernandes C, Ferreira J, Peris-Ortiz M (2018) Factors affecting SMEs’ strategic decisions to approach international markets. Eur J Int Manag. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2020.10018550

Lövingsson F, Dell’Orto S, Baladi P (2000) Navigating with new managerial tools. J Intellect Cap 1(2):147–154

Yeniaras V, Kaya I, Dayan M (2020) Mixed effects of business and political ties in planning flexibility: insights from Turkey. Ind Mark Manage 87:208–224

Lucianetti L, Jabbour CJC, Gunasekaran A, Latan H (2018) Contingency factors and complementary effects of adopting advanced manufacturing tools and managerial practices: Effects on organizational measurement systems and firms’ performance. Int J Prod Econ 200:318–328

Makadok R (2001) Toward a synthesis of the resource based and dynamic capability views of rent creation. Strateg Manag J 22(5):387–401

Makkonen H, Pohjola M, Olkkonen R, Koponen A (2014) Dynamic capabilities and firm performance in a financial crisis. J Bus Res 67:2707–2719

Maley JF, Dabic M, Moeller M (2020) Employee performance management: charting the field from 1998 to 2018. Int J Manpow 42(1):131–149

Menguc B, Dayan M (2020) The role of relational governance and dynamic capabilities for SMEs in B2B Market in Times of Crisis. Industrial Marketing Management (SI) article in press

Zafari K, Biggemann S, Garry T (2020) Mindful management of relationships during periods of crises: a model of trust, doubt and relational adjustments. Ind Mark Manage 88:278–286

Meyer N, Niemand T, Davila A, Kraus S (2022) Biting the bullet: When self-efficacy mediates the stressful effects of COVID-19 beliefs. PLoS ONE 17(1):e0263022

Mishkin FS (2011) Over the cliff: from the subprime to the global financial crisis. J Econ Perspect 25(1):49–70

Zahra SA, Sapienza HJ, Davidsson P (2006) Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: a review, model and research agenda. J Manage Stud 43(4):917–955

Moorman C (2020) Commentary: brand activism in a political world. J Public Policy Mark 39(4):388–392

Nakos G, Dimitratos P, Elbanna S (2018) The mediating role of alliances in the international market orientation-performance relationship of SMEs. Int Bus Rev 28(3):603–612

Obal M, Gao T (2020) Managing business relationships during a pandemic: conducting a relationship audit and developing a path forward. Ind Mark Manage 88:247–254

O'Connor G (2008) Major innovation as a dynamic capability: A systems approach. J Prod Innov Manag 25(2), 313–330

Zhang J, Wu WP (2017) Leveraging internal resources and external business networks for new product success: a dynamic capabilities perspective. Ind Mark Manage 61:170–181

Oura MM, Zilber SN, Lopes EL (2016) Innovation capacity, international experience and export performance of SMEs in Brazil. Int Bus Rev 25(4):921–932

Papaoikonomou E, Segarra P, Li X (2012) Entrepreneurship in the context of crisis: identifying barriers and proposing strategies. Int Adv Econ Res 18(1):111–119

Parker SC (2011) Entrepreneurship in Recession. Edward Elgar Pub., Massachusetts

Pedersen CL, Ritter T, Di Benedetto CA (2020) Managing through a crisis: managerial implications for business-to-business firms. Ind Mark Manage 88:314–322

Peteraf M, Di Stefano G, Verona G (2013) The elephant in the room of dynamic capabilities: bringing two diverging conversations together. Strateg Manag J 34(12):1389–1410

Pezeshkan A, Fainshmidt S, Nair A, Lance Frazier M, Markowski E (2016) An empirical assessment of the dynamic capabilities-performance relationship. J Bus Res 69(8):2950–2956

Porac J, Thomas H, Baden-Fuller C (1989) Competitive groups as cognitive communities: the case of Scottish Knitwear. J Manag Stud 26(4):397–416

Roemer E (2016) A tutorial on the use of PLS path modeling in longitudinal studies’. Ind Manag Data Syst 116(9):1901–1921

Ringle CM, Wende S, Becker JM (2015) SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH, https://www.smartpls.com. Access: May 2022

Zollo M, Winter S (2002) Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. ORgan Sci 13(3):339–351

Santos E, Fernandes C, Ferreira J (2020) The driving motives behind informal entrepreneurship: the effects of economic-financial crisis, recession and inequality. Int J Entrep Innov. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750320914788

Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Cheah JH, Becker JM, Ringle CM (2019) How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas Mark J 27(3):197–211

Schreyögg G, Kliesch-Eberl M (2007) How dynamic can organizational capabilities be? Towards a dual-process model of capability dynamization. Strateg Manag J 28(9):913–933

Singh SK, Del Giudice M (2019) Big data analytics, dynamic capabilities and firm performance. Manag Decis 57(8):1729–1733

Spry A, Figueiredo B, Gurrieri L, Kemper J, Vredenburg J (2021) Transformative branding: a dynamic capability to challenge the dominant social paradigm. J Macromark 41(4):531–546

Stoyanova V (2018) David J. Teece’s dynamic capabilites and strategic management: Organizing for innovation and growth. Routledge, Abingdon on Thames

Teece DJ (2018) Dynamic capabilities as (workable) management systems theory. J Manag Organ 24(3):359–368

Teece DJ, Pisano G, Shuen A (1997) Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg Manag J 18(7):509–533

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) (2019) UNDRR Annual Report 2019. Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.undrr.org/ Access: May 2022

Vahlne JE, Jonsson A (2017) Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability in the globalization of the multinational business enterprise (MBE): case studies of AB Volvo and IKEA. Int Bus Rev 26(1):57–70

Vlačić E, Dabić M, Daim T, Vlajčić D (2019) Exploring the impact of the level of absorptive capacity in technology development firms. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 138:166–177

Vredenburg J, Kapitan S, Spry A, Kemper JA (2020) Brands taking a stand: authentic brand activism or woke washing? J Public Policy Mark 39(4):444–460

Vrontis D, Basile G, Andreano MS, Mazzitelli A, Papasolomou I (2020) The profile of innovation-driven Italian SMEs and the relationship between the firms’ networking abilities and dynamic capabilities. J Bus Res 114:313–324

Wang CL, Ahmed PK (2007) Dynamic capabilities: a review and research agenda. Int J Manag Rev 9(1):31–51

Wendt C, Adam M, Benlian A, Kraus S (2021) Let’s connect to keep the distance: how SMEs leverage information and communication technologies to address the COVID-19 crisis. Inf Syst Front. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-021-10210-z

Wenzel M, Stanske S, Lieberman MB (2021) Strategic responses to crisis. Strateg Manag J 42(2):O16–O27

Wilden R, Devinney TM, Dowling GR (2016) The architecture of dynamic capability research identifying the building blocks of a configurational approach. Acad Manag Ann 10(1):997–1076

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MD: Conceptualization, and Writing—Review and Editing. MLR: Conceptualization, and Methodology. JJF: Conceptualization, and Formal analysis, CF: Conceptualization, Investigation, and Writing—Original Draft. PMV: Resources, and Data Curation. LF: Conceptualization, and Writing—Original Draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Acknowledegement This work is financed by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I. P., under the project "UIDB/04630/2020".

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dejardin, M., Raposo, M.L., Ferreira, J.J. et al. The impact of dynamic capabilities on SME performance during COVID-19. Rev Manag Sci 17, 1703–1729 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00569-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00569-x