Abstract

In response to the euro area crisis, policymakers took a gradual, incremental approach to official lending, at first relying on the blueprint followed by the International Monetary Fund, then developing their own crisis resolution framework. We describe this process of institutional development, marked by a substantial divergence in the terms of official loans offered to. We use a unique dataset of the characteristics of the various official loans to provide key stylised facts, and use regression and event analysis techniques to study the effect of different lending terms on market borrowing costs and fiscal performance. Euro area loans, when in longer maturities and lower rates, go hand in hand with improved market access. Instead, the terms of IMF loans appear to have no significant effect on market access, but primary balances are larger when IMF maturities are longer. We discuss arguments for refocusing debt sustainability analysis and embed debt management techniques in programme design, while considering the trade-off between adjustment incentives and official lending.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Reinhart and Trebesch (2016) for a historical perspective on the IMF activities.

While there was some prior experience of IMF-EU cooperation in providing official lending to Eastern European countries through the medium-term financial assistance, this route was not available for euro area countries.

Our Online Appendix describes the mechanics of the interaction of the various institutions involved in the Troika.

This step back was the result of an internal evaluation of the IMF’s role in Europe (International Monetary Fund 2013a). The evaluation called for a review of the framework to evaluate debt sustainability analysis for market access countries.

International Monetary Fund (2016c) noted that for the DSA to remain credible, euro area and IMF needed to realignment assumptions.

Our dataset Official Loans to Euro Area Countries is available for researchers to use (see Online Appendix).

A non-exhaustive list of institutions using DSA frameworks includes International Monetary Fund, World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, European Commission, European Central Bank or European Stability Mechanism.

For example, the 2007 euro area Article IV consultation stated that the outlook was the best in years.

Not only Article 143 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union excluded Euro area countries from accessing this facility, in addition, Article 125 prevented cross-country fiscal financing (no bail-out clause).

Ardagna and Caselli (2014) review the events that led to the May 2010 and July 2011 bailout agreements, and interpret them as outcomes of political-economy equilibria.

The programme did not include a bank creditors’ bail-in, as desired by the authorities.

Moschella (2016) explains why the European Central Bank and the European Commission relaxed their opposition to debt restructuring and fiscal accommodation for Greece in the shift from the first to second adjustment program.

Given its originally larger interest charges, the Irish spread reduction was also larger.

Lending is conditional on a country’s debt being sustainable, conditional on: (a) reforms and policy measures able to redress fundamental weaknesses, and (b) the mobilisation of enough financial resources.

In 2016, the IMF revised the pricing of its lending facilities (International Monetary Fund 2016a). It increased the cost of loans by reducing the size above which they are considered large, while making it cheaper to borrow for longer periods.

Seniority was waived in the case of the Spanish programme because the programme was agreed under the EFSF and loan conditions were grandfathered. Seniority applies to the programmes in Cyprus and Greece.

Differences exist also in terms of funding structures. While IMF loans are financed using the Fund’s quotas, euro area official lenders behave like financial intermediaries: they finance programmes by issuing debt in capital markets. For a comparative discussion of governance and decision-making structures, see Henning (2017).

As the focus is on whether a programme was in place or not, these regressions allow us to use more observations than the specifications in Columns 5 to 10, where we study the terms of the loans.

Column 1 reports OLS results, column 2 includes country fixed effects, and column 3 adds time fixed effects.

Judson and Owen (1999) note that the Nickel bias generated by the inclusion of the lagged dependent variable can be large when T is smaller than 20. Our size of T is above that threshold, which makes us confident that the potential bias may not be large.

The Deauville declaration should have pushed rates higher. Instead, we document a negative correlation.

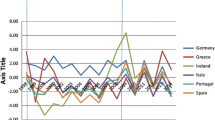

The programme changes are detailed above. We summarise them here for convenience. Ireland received 40.2 billion euros from the euro area in December 2010, with a margin over funding costs of 250 bps and a maturity of 7.5 years. In July 2011, the authorities eliminated the margin and an extended the maturity to 15 years. In May 2013, a further 7-year maturity extension was agreed. Portugal received its programme in May 2011, with 52 billion disbursed by the euro area with a 210 bps margin and maturity of 7.5 years. In July 2011, the maturity was extended to 15 years and the margin reduced to 0 bps. In May 2013, maturities were extended to 22 years.

The numbers correspond to the average of the daily observations in the corresponding month.

According to the 2012 Eurogroup agreement, reaching a debt-to-GDP ratio of 124% in 2020, and remaining substantially lower than 110% in 2022, would ensure Greece’s debt sustainability.

The Euro group statement agreeing to monitor GFN while evaluating debt sustainability can be found here

According to the IMF, in advanced economies, GFN should not be consistently below 20% of GDP.

Following European Stability Mechanism (2015), a cap of 6.4% is applied to the market rate.

The comparison does not consider SDR hedging costs, nor IMF fees, but includes fees charged by the EFSF/ESM. Thus, our numbers are a lower bound on savings. We should note that the figure does not.

In another paper included in this special volume, Konstantinidis and Karagiannis (2020) argue that after accessing the European Union countries show reform fatigue.

Dell'Ariccia et al. (2006) test for moral hazard effect attributable to official crisis lending by analysing the evolution of sovereign bond spreads in emerging markets before and after the Russian crisis.

Bulow and Geanakoplos (2017) argue that more back loaded loans incentivise rebuilding fiscal capacity.

Corsetti et al. (2006) emphasise that polices that eliminate self-fulfilling crises strengthen effort.

Redeker and Walter (2020), also part of this volume, discuss another interesting aspect of moral hazard by focusing on the redistribution aspects of the euro area response to the imbalances underlying the crisis. According to Redeker and Walter (2020), Germany does not rebalance its persistence current account surplus, despite pressure from other countries, because the policies that would lead to adjustment would have strong distributional consequences within Germany. In this situation, Germany opts for policies such as bailouts or debt haircuts as they face least opposition.

The seniority of EFSM and GLF is unclear. Bilateral lenders are the least senior creditors (Schlegl et al. 2019).

Mody and Saravia (2006) find that larger loans are more catalytic.

If the government is expected to tax to reduce the debt, investment will be discouraged (Nikiforos et al. 2016).

We thank Nikos Ventouris for his help in preparing this summary.

The new programme included a debt restructuring that brought 100 billion of NPV relief (Gulati et al. 2013).

We thank Daragh Clancy and Carmine Gabriele for their help in preparing this summary.

The programme also included an Irish contribution of 17.5 billion euro.

We thank Ricardo Santos for his help in preparing this summary.

This lower spread likely reflected that the Greek and Irish programmes were both performing below expectations.

We thank Saioa Armendariz for her help in preparing this summary.

We thank Lorenzo Ricci for his help in preparing this summary.

As a consequence, the banking sector grew until its assets reached 7.5 times GDP in 2010.

References

Abraham, A., Carceles-Poveda, E., Liu, Y., & Marimon, R. (2019). On the Optimal Design of a Financial Stability Fund. ADEMU Working Paper 105.

Alesina, A., Furceri, D., Ostry, J., Papageorgiou, C., & Quinn, D. (forthcoming). Structural reforms and election: Evidence from a world-wide new dataset. Journal of Economic Literature

Ardagna, S., & Caselli, F. (2014). The political economy of the Greek debt crisis: A tale of two bailouts. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 6(4), 291–323.

Balassone, F., & Committeri, M. (2015). Europe and the IMF: nec sine te, nec tecum. LUISS School of European Political Economy Working Paper No. 6/2015

Ban, C., & Gallagher, K. (2015). Recalibrating policy orthodoxy: The IMF since the great recession. Governance, 28(2), 131–146.

Bassanetti, A., Cottarelli, C., & Presbitero, A. (2019). Market access and public debt dynamics. Oxford economic papers, 71(2), 445–471.

Bird, G., & Rowlands, D. (2003). Political economy influences within the life-cycle of IMF Programmes. The World Economy, 26, 1255–1278.

Bolton, P., & Jeanne, O. (2007). Structuring and restructuring sovereign debt: The role of a bankruptcy regime. Journal of Political Economy, 115(6), 901–924.

Buchheit, L., & Gulati, M. (2018). Sovereign debt restructuring in Europe. Global policy 9(1), 65–69.

Bulow, J., & Geanakoplos, J. (2017). Greece’s sovereign debt and economic realism. CEPR Policy Insights No. 90.

Caraway, T., Rickard, S., & Anner, M. (2012). International negotiations and domestic politics: The case of IMF labor market conditionality. International Organization, 66, 27–61.

Cheng, G. (2016). The Global Financial Safety Net through the Prism of G20 Summits. ESM Working Paper No. 13.

Consiglio, A., & Zenios, S. (2015). Risk management optimization for sovereign debt restructuring. Journal of Globalization and Development, 6(2), 181–213.

Corsetti, G., Guimaraes, B., & Roubini, N. (2006). International lending of last resort and moral hazard: A model of IMF's catalytic finance. Journal of Monetary Economics, 53(3), 441–471.

Corsetti, G., Erce, A., & Uy T. (2018). Debt Sustainability and the Terms of Official Support. CEPR Discussion Paper 13292

De Ferra, S., & Mallucci, E. (2020). Avoiding Sovereign Default Contagion: A Normative Analysys (p. 1275). International Financial Discussion papers.

Dell'Ariccia, G., Schnabel, I., & Zettelmeyer, J. (2006). How do official bailouts affect the risk of investing in emerging markets? Journal of money. Credit and Banking, 38(7), 1689–1714.

Dias, D., Richmond, C., & Wright, M. (2014). The stock of external sovereign debt: Can we take the data at face value? Journal of International Economics, 94(1), 1–17.

Diaz-Cassou, J., & Erce, A. (2011). IMF interventions in sovereign debt restructurings. In In “Sovereign Debt: From Safety to Default”. Wiley.

Dreher, A. (2004). Does the IMF cause moral hazard? A critical review of the evidence. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=505782.

Dür, A., Moser, C. and G. Spilker (2020). Introduction to special volume “The Political Economy of the European Union”. Review of International Organizations.

European Commission. (2016). Evaluation of the financial sector assistance Programme. Spain, 2012-2014 (p. 019). Institutional Paper.

European Commission, IMF, ECB, & ESM. (2014). Impact of early repayment of IMF credit on Irish public debt sustainability. Joint note for the Economic and Financial Committee.

European Financial Stability Facility (2010), Master Financial Assistance Facility Agreement between EFSF and Ireland.

European Financial Stability Facility (2011), Master Financial Assistance Facility Agreement between EFSF and Portugal.

European Stability Mechanism (2015), Annual Report.

European Stability Mechanism (2017), ESM/EFSF Financial Assistance. Evaluation Report.

Foley-Fisher, N., Ramcharan, R., & Yu, E. (2016). The impact of unconventional monetary policy on firm financing constraints: Evidence from the maturity extension programme. Journal of Financial Economics, 122(2), 409–429.

G-20 (2016), Final Report by the International Financial Architecture Working Group.

Ghezzi, P. (2012). Official lending: Dispelling the lower recovery value myth. Vox EU (June).

Gourinchas, P. O., & Rey, H. (2017). Real interest rates, Imbalances and the Curse of Regional Safe Asset Providers at the Zero Lower Bound. Prepared for the ECB Forum on Central Banking.

Greek Public Debt Management Agency. Hellenic Republic Debt Bulletin: 2010–2015 (all issues).

Gros, D. (2010). The seniority conundrum: Bail-out countries but bail in private short-term creditors? Vox EU Column (December).

Grund, S., & Stenstrom, M. (2019). A Sovereign Debt Restructuring Framework the Euro Area. A Framework for Sovereign Debt Restructuring in the Euro Area. Fordham Journal of International Law journal, 42(3), 795.

Gulati, M., Trebesch, C., & Zettelmeyer, J. (2013). The Greek debt restructuring: An autopsy. Economic Policy, 28(75), 513–569.

Hagan, S., Obstfeld, M., & Thomsen P. (2017). Dealing with Sovereign Debt - The IMF Perspective. IMF Blog (February, 2017).

Henning, R. (2011). Coordinating Regional and Multilateral Financial Institutions. Peterson Institute for International Economics (pp. 11–19). Working Paper.

Henning, R. (2017). tangled governance: International regime complexity, the troika, and the euro crisis (New York: Oxfod University press). The Review of International Organizations, Springer, 13(3), 483–485.

International Monetary Fund (2007). Euro area policies: Staff Report for the 2007 Article IV Consultation with Member Countries. IMF Country Report No. 07/260.

International Monetary Fund (2013a). Greece: Ex-post Evaluation of Exceptional Access under the 2010 Stand-By Arrangement. IMF Country Report No.13/156.

International Monetary Fund. (2013b). Staff guidance note for public debt sustainability analysis in market-access countries. In IMF Policy Papers.

International Monetary Fund. (2013c). Sovereign debt restructuring – Recent developments and implications for the Fund’s legal and policy framework. In IMF Policy Papers.

International Monetary Fund. (2014). The Fund’s lending framework and sovereign debt – Preliminary considerations. In IMF Policy Papers.

International Monetary Fund. (2016a). Review of access limits and surcharge policies. In IMF Policy Papers.

International Monetary Fund. (2016b). IMF reforms policy for exceptional access lending. In IMF Survey.

International Monetary Fund (2016c). Greece: Preliminary debt sustainability analysis—Updated estimates and further considerations, May 2016. IMF Country Report No. 16/130.

International Monetary Fund (2017). Adequacy of the Global Financial Safety Net – Considerations for Fund Toolkit Reform. Policy Document SM/16/285.

International Monetary Fund. (2019). The 2018 Review of Programme Design and Conditionality. In IMF Policy Paper No. 19/012.

Jost, T., & Seitz, F. (2012). The Role of the IMF in the euro area Debt Crisis. In Weidener Discussion Paper No. 32.

Judson, R., & Owen, A. (1999). Estimating dynamic panel data models: a guide for macroeconomists. Economics Letters, 65(1), 9–15.

Konstantinidis, N., & Karagiannis, Y. (2020). Intrinsic vs. extrinsic incentives for reform: An informational mechanism of E(M) U conditionality. Review of International Organizations, 15(3).

Lane, P. R., & Milesi-Ferreti, G. M. (2018). The external wealth of nations revisited: International financial integration in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. IMF Economic Review, 66, 189–222.

Lane, T., & Phillips, S. (2002). Moral Hazard: Does IMF financing encourage imprudence by borrowers and lenders? In International Monetary Fund, Economic Issues No. 28.

Lee, J., & Shin, K. (2008). IMF bailouts and moral hazard. Journal of International Money and Finance, 27(5), 816–830.

Lipscy, P., & Lee, H. (2019). The IMF as a biased global insurance Mechanism: Asymmetrical moral Hazard, reserve accumulation, and financial crises. International Organizations, 73(1), 35–64.

Meltzer, A. H. (1998). Asian problems and the IMF. The Cato Journal, 17(3), 267–274.

Mody, A., & Saravia, D. (2006). Catalysing private capital flows: Do IMF-supported programmes work as commitment devices? The economic journal, 116. Issue, 513, 843–867.

Moreno, P. (2014). The IMF getting what it needs in (as) the aftermath of the crisis. Estudios de Economia Aplicada, 32(3), 935–962.

Morris, S., & Shin, H. (2006). Catalytic finance: When does it work? Journal of international economics, 70(1), 161–177.

Moschella, M. (2016). Negotiating Greece: Layering, insulation, and the design of adjustment programmes in the Eurozone. Review of International Political Economy, 23(5), 799–824.

Müller, A., Storesletten, K., & Zilibotti, F. (2016). The political color of fiscal responsibility. Journal of the European Economic Association, 14(1), 252–302.

Nikiforos, M., Papadimitrou, D. B., & Zezza, G. (2016). The Greek public debt problem. In Levy Economics Institute of Bard College Working Paper N°.867.

Nunnenkampp, P. (1999). The moral hazard of IMF lending: Making a fuss about a minor problem? In Kiel discussion papers, No. 332.

Pagoulatos, G. (2018). Greece after the Bailouts: Assessment of a Qualified Failure. In GreeSE Paper No.130. Hellenic Observatory Papers on Greece and Southest Europe. European Institute.

Pisani-Ferry, J., Sapir, A., & Wolff, G. (2013). EU-IMF assistance to euro area countries: an early assessment. In Bruegel Blueprint 19 Policy Paper.

Redeker, N. & Walter, S. (2020). We’d rather pay than change – The politics of German non-adjustment in the Eurozone crisis. Review of International Organizations, 15(3).

Reinhart, C. M., & Trebesch, C. (2016). The International Monetary Fund: Seventy years of reinvention. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(1), 3–28.

Reinhart, C. M., Reinhart, V. R., & Rogoff, K. S. (2012). Public debt overhangs: Advanced-economy episodes since 1800. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(3), 69–86.

Roch, F., & Uhlig, H. (2018). The dynamics of sovereign debt crises and bailouts. Journal of International Economics, Volume, 114, 1–13.

Sandri, D. (2015). Dealing with Systemic Sovereign Debt Crises: Fiscal Consolidation, Bail-ins or Official Transfers? In IMF Working Paper 15/233.

Saravia, D. (2010). On the role and effects of IMF seniority. Journal of International Money and Finance, 29(6), 1024–1044.

Schadler, S. (2013). Unsustainable Debt and the Political Economy of Lending: Constraining the IMF’s Role in Sovereign Debt Crises. In CIGI Papers 19.

Schadler, S. (2014). The IMF’s Preferred Creditor Status: Does it still Make Sense after the Euro Crisis? In CIGI Policy Brief 37.

Schlegl, M., Trebesch, C., & Wright, M. (2019). The Seniority Structure of Sovereign Debt. In NBER Working Papers 25793.

Schumacher, J., & di Mauro, B. W. (2015). Greek Debt Sustainability and Official Crisis Lending. In Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 279–305.

Simpson, L. (2006). The Role of the IMF in Debt Restructurings: Lending Into Arrears, Moral Hazard and Sustainability Concerns. In G-24 Discussion Paper Series 40, UNCTAD.

Steinkamp, S., & Westermann, F. (2014). The role of creditor seniority in Europe's sovereign debt crisis. Economic Policy, 29(79), 495–552.

Vaubel, R. (1983). The moral Hazard of IMF lending. The World Economy, 6(3), 291–304.

Zeng, L. (2014). Determinants of the Primary Fiscal Balance: Evidence from a Panel of Countries. In “Post-crisis Fiscal Policy” (MIT Press).

Zettelmeyer, J., Kreplin, E., & Panizza, U. (2017). Does Greece Need More Official Debt Relief? If So, How Much? In Peterson Institute for International Economics, Working Paper 17–6.

Acknowledgements

We thank Cornel Ban, Javi Diaz-Cassou, Gong Cheng, Antonio Fernandes, Jon Frost, Mitu Gulati, Christopher Kilby (discussant), Pablo Moreno, Manuela Moschella, Stathis Sofos, Tiago Tavares (discussant), Vilem Valenta, Carlos Van Hoombeck, Mark Walker, the Editors, three anonymous referees, and seminar participants at Banca d’Italia 20th Fiscal Workshop, Warwick University, University of Cagliari, Centre of European Policy Studies, Florence School of Banking Conference “Institutions and the Crisis”, ESM Workshop “Debt Sustainability: Current Practice and Future Perspectives”, PEIO Conference 2019, GIC/Drexel Conference “Sovereign Debt Distress, Restructurings and Market Access”, LUISS, and Inter-American Development Bank for their comments. Ande Erce provided superb editorial support. Part of this work was prepared while Aitor Erce was a visiting fellow at the Robert Schuman Centre of the European University Unversity. Aitor acknowledges the kind support of the Pierre Werner Chair. Corsetti’s work on this paper is part of the ADEMU project, “A Dynamic Economic and Monetary Union”, funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Programme under grant agreement N° 649396 (ADEMU). Corsetti’s work on this paper is also supported by the Keynes Fund in Cambridge, as part of the project: “The Making of the Euro-area Crisis: Lessons from Theory and History.” The views in this paper are strictly the authors’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

1.1 A summary of the euro area programmes

1.1.1 Greece

In late 2009, after recognising they had manipulated their fiscal accounts, the Greek Government approached its euro area partners asking for help, who at first asked for a significant fiscal adjustment.Footnote 38 As this strategy failed and the situation span out of control, in March 2010, euro area governments agreed to provide, together with the IMF, a 110 billion EUR financial assistance package, composed of an IMF credit and bilateral loans from euro area members (Greek Loan Facility, GLF). The GLF contributed with 80 billion euro, with a maturity of 5 years and a 3-year grace period. Its pricing, similar to IMF practice, was organised in steps. For its part, the IMF contributed a 30 billion euro Stand-by-Agreement with 3-years duration, a maturity of 5 years, the standard 200 bps for credit above 300% of the quota, and additional 100 bps for credit outstanding after 3 years.

By mid-2011, in spite of reviews of the first programme speaking of “an impressive start”, the situation took a turn for the worst. The reasons for the setback were excessively optimistic projections, initial official indecision, weak programme implementation and the excessive cost of initial funding conditions. The reaction of the authorities was to provide additional support by modifying the terms of the GLF. In spite of these additional measures, by early 2012, it became clear that Greece would not make it without a contribution from its shrinking private-sector creditor base. In March 2012, Greece signed a second programme with the official lenders.Footnote 39 The new programme, signed by the EFSF and the IMF, envisioned 130 billion euros of additional funding. From the 130 billion euros, 25 billion came from a new 4-year IMF EFF programme, and the rest was provided by the EFSF, with a 20-year maturity and 150 bps margin. The terms, of the EFSF and GLF loans were further softened in December 2012.

For a brief period, this second programme appeared to be working. The situation in Greece improved, and with it, expectations of the country being able to regain market access. Political turmoil (the country even underwent a referendum on the euro membership), however, led to the second programme also going off-track. In the final stage, in September 2015, Greece entered into a new 3-year 86 billion euro programme with the ESM.

1.1.2 Ireland

In Ireland, banks had fuelled a mortgage boom in the years prior to the global crisis.Footnote 40 As a result, the price for real estate had more than tripled in a decade. When the bubble burst, to prevent a financial collapse, the government was forced to provide support from its taxpayers (?) to the country’s financial institutions.

In December 2010, overburdened by the burst of the housing bubble and the subsequent bailout of its banking system, Ireland became the first client of the EFSF and the EFSM. The Irish programme, designed to re-establish a sound economic and financial situation and to restore its capacity to finance itself on the financial markets, provided a financing package of 85 billion euros, to be disbursed between 2010 and 2013. It included contributions by the EFSM (22.5 billion) and EFSF (17.7 billion), and bilateral loans from UK, Sweden and Denmark (3.8, 0.6 and 0.4 billion respectively).Footnote 41 The maturity of the loan was set at 7.5 years and the margin at 250 bps. Additionally, Ireland signed a 7 year EFF agreement with the IMF for 22.5 billion euro.

Despite the official support, by mid-2011, spreads had crept up to unsustainable levels. According to Pisani-Ferry et al. (2013), the bad performance was the result of the effect of excessively rapid deleveraging and the bail-out of the banks’ junior creditors on public debt. In an attempt to provide further support to Ireland, the terms of the financial agreement were modified in July 2011. In addition to fully eliminating the margin for both EFSM and EFSF loans, the maturity of both loans was extended by seven years, to a maximum of 15 years. An additional, and final, change in the financing terms occurred in April 2013, when authorities decided that EFSF and EFSM loan maturities would be further extended to 22 years.

During its 3-year assistance programme, Ireland improved its financial regulation, and major banks were closed down, while some of the remaining firms received a capital boost. A bad bank was set up to deal with non-performing loans. In addition, the country reduced its fiscal deficit and regained the competitiveness it lost during the boom. This led to a successful exit from the EFSF programme in December 2013.

1.1.3 Portugal

Portugal’s economic growth was already weak before the crisis.Footnote 42 This lack of dynamism contributed to high levels of debt, both public and private. When the global crisis hit Europe in 2010, the country had little fiscal space to support the economy or the banks, which also became the focus of investors, who were concerned that Portuguese banks were too dependent on a weak economy. Investors responded by demanding ever-higher returns on Portugal’s bonds.

In April 2011, Portugal requested support to re-establish a sound economic situation and restore its capacity to finance itself on the financial markets. In this case the financing of the 78 billion euro programme fell on equal parts on the EFSM, EFSF and IMF. While the maturity was set to 7.5 years, as in Ireland, the margin was lower, about 210 bps.Footnote 43 In turn, Portugal signed a 26 billion euro 3-year EFF programme with the IMF.

By mid-2011, the programme was at risk of going off-track. According to Pisani-Ferry et al. (2013), the programme relied on the implementation of structural reforms which did not materialise. In reaction to these negative developments, the EFSF and the EFSM granted an improvement in the conditions of the loans to the Portuguese authorities. Thus, on July 2011, the euro area governments decided to fully eliminate the margin for both EFSM and EFSF loans and to extend the maturity of EFSM and EFSF loans to a maximum of 15 years. In order to maintain identical conditions in Portugal and Ireland, identical to what was done with the Irish loan, a final change in the terms of the EFSF and EFSM programmes occurred in April 2013. On that date, authorities decided that EFSF and EFSM loan maturities would be extended by an additional 7.5 years to 22 years.

The funds received from the official sector were used by the authorities to finance budget deficits and recapitalise the banks. In accordance with the conditionality, Portugal embarked on policies to bring down budget deficits, resolve its banking problems and modernise its economy. The programme helped the economy to recover, and as it became more competitive, exports started to grow, the account deficit was eliminated, budget deficits were significantly reduced, and growth resumed. Portugal regained market access and exited the programme in June 2014.

1.1.4 Spain

In June 2012, Spain requested financial assistance under the terms of Financial Assistance for the Recapitalisation of Financial Institutions by the EFSF.Footnote 44 This came in response to the increasing financial stress of the Spanish economy, materialized in the accumulation of strong capital outflows, mostly from non-resident sectors. This translated into a record high spread against the 10-year Bund since the implementation of the Euro (do we need caps?). Increasing the resilience of the banking sector, in particular of the saving banks (“Cajas”) with heavy real estate-related portfolios, was essential to restore market confidence and stabilise the economy.

Initially, it was envisaged that this Financial Assistance was to be provided by the EFSF until the ESM became fully operational. Eventually, the ESM became operational in time to address the assistance from the onset. The programme created for Spain was not designed to tackle a balance of payments problem, but rather a structural problem on the banking system. Reflecting the specific focus of the programme, the attached conditionality contained in the MoU only addressed financial sector issues, but also required Spain to fully comply with its commitments under the EDP and European Semester recommendations. Unlike standard economic adjustment programmes, this did not contain new specific conditions in fiscal policies and structural reforms. As a result, the programme design and implementation deviated so much from the IMF’s programme template that the Fund could not participate financially. In this way, Spain became the first euro area country to be treated by the euro area safety net in financial solitude. The main objective of the programme was to increase the long-term resilience of the banking sector, by removing doubts about asset quality, orderly downsizing bank exposures to the real estate sector, restoring market-based funding, and enhancing risk identification and crisis management mechanism (European Commission 2016).

The ESM programme granted the authorities access to up to 100 billion euro, about 10% of GDP. Eventually, only 41.3 EUR bill were actually disbursed in two tranches, the first in December 2012 and the second in February 2013. Later, Spain made a repayment of 0.3 EUR bill related to the unused funds in 2014, which according to the terms of the ESM facility must be returned to the ESM. The loan had at its inception a 12.5 years maturity. Following the pricing guidelines of the ESM, Spain was charged a 50 bps margin. By June 2017, Spain had made five voluntary early repayments of 7.3 EUR bill, almost 20% of the borrowed funds.

1.1.5 Cyprus

Cyprus joined the euro in 2008, which allowed it to borrow cheaply to support the economy, which had weakened following the global crisis.Footnote 45 The first signs of distress in the banking sector appeared in 2010. The banks had grown too rafpidly. The ratios of deposits and liquid liabilities to GDP were the highest in Europe. The Cypriot regulatory framework contributed to the large inflows of capital into the country’s banks and property market.Footnote 46

Markets started to take a negative view. By mid-2011, Cyprus was no longer able to borrow money from investors. Cyprus addressed a request for stability support to the ESM and the IMF on June 2012. The economic adjustment programme was intended to address short and medium-term financial, fiscal and structural challenges facing Cyprus. Following a severe downturn that reduced the quality of the lending portfolio, and faced with losses on the holdings of Greek sovereign bonds, the banking system in Cyprus went into severe distress. The key programme objectives were to restore the soundness of the Cypriot banking sector and rebuild market confidence by restructuring and downsizing financial institutions.

In Cyprus, the template replicated earlier EFSF programmes, and both the ESM and the IMF contributed to the programme. The ESM contributed with EUR 9 bill and the IMF with 1 EUR 1 bill respectively. The IMF provided support under a 7-year EFF agreement with the usual pricing structure. In turn, the ESM loan to Cyprus had a 15 year maturity, extending up to 2030. The margin charged by the ESM is 10 bps.

Following programme conditionality, Cyprus restructured its banking system, improved financial regulation and supervision, and modernized its legal framework (to help deal with the nonperforming loans). Additionally, fiscal deficits shrunk, mitigating sustainability concerns. As a result, Cyprus gradually regained market access, and exited the programme in March of 2016.

Appendix 2

1.1 Econometric evidence - Market Access, Fiscal Effort and Official Loans

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Corsetti, G., Erce, A. & Uy, T. Official sector lending during the euro area crisis. Rev Int Organ 15, 667–705 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-020-09388-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-020-09388-9