Abstract

The characteristics of neighbourhoods, their physical and social environment, have been shown to have profound effects on the individual well-being and happiness of their residents. In an effort to help design policies and action plans that enhance well-being in the district, our study seeks to understand how happiness levels among residents in a low-income neighbourhood in Spain are linked to their socio-demographic traits, individual health, relationships with the area, and community, as well as with the physical environment of the neighbourhood. The study is part of a project called "Educa-Pajarillos Sostenible". The project aims to improve the quality of life of the area’s citizens by carrying out a series of actions. One of these actions is an eco-social map of happiness, which involves designing and applying a survey and which serves as a source of analysis for our research. An Ordered Choice Logit econometric model was applied to measure the effect of the happiness of demographic, neighbourhood environment, social capital, and socio-demographic characteristics. Results confirm the importance of variables related to the neighbourhood’s social capital and physical environment as key elements in local residents’ happiness. The findings also indicate that traditional indicators used to measure well-being, such as education or difficulty making ends meet, are not significant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Determining what actions can be taken in neighbourhoods to increase the subjective well-being of their citizens is a fundamental issue for social policy. Understanding the mechanisms through which neighbourhood environments affect people’s lives proves crucial to decision-makers when designing plans, policies or project actions. The topic becomes even more interesting when analysing subjective well-being in a low-income neighbourhood, as it can provide useful information for policy decisions vis-à-vis improving the quality of life of the residents in such areas, who live in very disadvantaged situations.

Wenz (1977) states that the non-verbal behaviours of social and psychological disequilibrium and economic status features of neighbourhoods can be considered as indices of relative happiness. The same author says that the experience of living in a poor neighbourhood can affect a person’s psychological well-being.

Neighbourhoods have received much research attention in terms of social cohesion and related concepts of interpersonal relationships, civic participation and feelings of reciprocity. Specifically, good relations in neighbourhoods appear to positively affect happiness and life satisfaction (Taniguchi & Potter, 2016). The neighbourhood community is a form of social environment that has evidenced profound effects on individual well-being and happiness (Mcmillan, 2011; Ross & Mirowsky, 2001). Neighbourhood environment characteristics that seem most directly related to residents’ happiness include access to open, natural and green spaces, which are design features that allow for social interaction.

When addressing research into happiness in neighbourhoods that have a low economic status, we must take into account that subjective well-being is configured differently to the rest of the population, which may mean that traditional socio-economic indicators are not significant. As pointed out by Rojas (2005), there are major differences between people in the perception of what appear to be objectively identical circumstances. This seems to be because people have different conceptual referents in the subjective evaluation of their well-being, and is clearly manifested when studying happiness in neighbourhoods that face conditions of vulnerability. As highlighted by Wenz (1977), the neighbourhood attribute of economic status is more important for differences in happiness than individual economic status. This is because the conceptual referent in vulnerable neighbourhoods differs to the referents in the rest of society.

Our study seeks to understand how happiness levels among residents in one particular low-income neighbourhood in Spain are linked to socio-demographic characteristics, individual health, relationships with the neighbourhood and the community, as well as with the neighbourhood’s physical environment. The study is framed within a project called “Educa-Sustainable Pajarillos” in which different agents and political institutions are involved. The project aims to improve the quality of life of citizens in the area by undertaking a series of initiatives. One of these initiatives is to develop an eco-social map of happiness that involves designing and implementing a survey that serves as a source of analysis for our research.

The research seeks to determine which factors are significant in explaining the happiness of citizens in order to then design policies and action plans aimed at increasing the well-being of a neighbourhood which, because of its economic situation, historical characteristics and the presence of architectural barriers, is vulnerable in social and economic terms. The study explores the possibility that social capital (at both an individual and a community level), health behaviour, and the physical environment of the neighbourhood may increase local residents’ happiness. We also expect certain individual factors such as gender, age, education, income and/or labour status to have little or only an insignificant effect on local residents’ happiness due to these traditional socioeconomic indicators losing significance in situations of vulnerability and because of the role played by the previously cited referents.

The paper is organized as follows. The first section provides a literature review of studies that address what impact the neighbourhood where people live has on individual happiness outcomes. In the following section, we briefly describe the Educa-Sustainable Pajarillos project in an effort to understand the motivation underlying this research. The method section describes the survey and the measures used in the econometric analysis. In the fifth section, we present the results of our econometric model and the principal factors that explain happiness. Finally, a discussion of the results and some proposals for action conclude the paper.

2 Background

The question concerning which factors affect individuals’ subjective well-being has generated a vast amount of literature, and there are many models and theories that attempt to provide an answer to this question. Depending on the discipline from which the study is approached, the historical moment and the cultural context, different answers emerge.

This research does not seek to offer a detailed description of the many studies that in one way or another have explored which factors can affect our happiness. We confine ourselves to citing two papers that attempt to show the most common factors to emerge when addressing this question. Dolan et al. (2008) considered that the potential influences on well-being identified in the literature are income, personal characteristics, socially developed characteristics (education, health, work), how we spend our time (community enrolment and volunteering, exercise…), attitudes and beliefs towards self/others/life (trust, religion…), relationships (marriage and intimate relationships, seeing family and friends…) and the wider economic, social and political environment (nature, environment, urbanization…). Another very interesting article is The Big Seven Factors for Explaining Happiness by Layard (2005), which offers an excellent summary of these factors. In his work, the author identifies the ‘Big Seven’, or the most important factors that affect subjective well-being. These have been used effectively to explain how happiness is generated in diverse contexts (Leyden et al., 2011). These seven factors are family relationships, financial situation, work, community relations (social capital), health, personal freedom, personal values or perspective on life, where the first five are given in order of importance, according to the author. Both studies show that we face a concept—subjective well-being—which is endowed with a multidimensional nature and which depends on a wide variety of factors. Although the two works organize the components of subjective well-being in different ways, there are similarities between them.

It should be remembered that this research aims to study which factors affect happiness in a particular neighbourhood that displays a very specific character. Furthermore, the main intention of this paper is to facilitate decision-making or to propose initiatives to improve local residents’ quality of life. Therefore, when addressing which factors individuals’ subjective well-being depend on, we must take into account the perspective of the neighbourhood, and how both it and the policies adopted in its context can help to increase well-being.

2.1 Economic, Social and Political Environment

Some authors have sought to measure what effect the place we live in (social, economic and physical environment) has on our reported subjective welfare. For example, Lora et al. (2010) study the impact of public goods on life satisfaction as a whole, and other life domains such as leisure, social life, family, health, economic situation, and work. Gandelman et al. (2012) suggest that differences in overall happiness and in domain satisfaction can be partly explained by different levels of access to public goods. Other authors, such as Kwon, Pickett, Lee, & Lee (2019), have found that perceived walkability and neighbourhood appearance play a significant role in increasing residents’ well-being. In general, highly walkable communities foster social inclusion and the development of social capital, as pointed out by these authors. A more walkable environment and street network design has been found to promote neighbourly interactions and the development of social capital (Leyden, 2003). Moreover, walkability is connected with the safety of the neighbourhood, as reported by Wood et al. (2010) and Wood et al., (2008) “the more people out walking, the safer the neighbourhood is for those who walk”. People’s physical and social activities are influenced by the physical environment of the neighbourhood based on the social ecological model (Sallis et al., 2010; Wood et al., 2008). In this sense, other authors study the impact of third places on community quality of life (Jeffres et al., 2009). These third places are the great and good places that foster community and communication among people outside their home and work (Oldenburg, 1989). These third places include public spaces where people meet, congregate, and communicate. The presence of such places in neighbourhoods, which facilitate social contact, has been addressed by certain authors who explore the relationships between social capital, neighbourhood, and happiness.

One possible definition of social capital is the following; social capital consists of the stocks of active connections among people, trust, mutual understanding, shared values and behaviours that bind the members of human networks and communities and that make cooperation possible (Cohen & Prusak, 2001). People are happier if they feel that the people in their community can be trusted. This public or social trust is a primary indicator of social capital (Putnam, 2000). This concept includes key components such as reciprocity (e.g. number and type of favour exchanges with neighbours) or civic engagement (e.g. participation in voluntary work) (Wood et al., 2010), amongst others. Trust and relationships with others and their community are influenced by neighbourhood design and aesthetics, perceptions of local safety and opportunities to forge local support and social networks (Wood, 2006). People are happier when living in a community which they believe can be trusted (Leyden et al., 2011, p. 865).

Earlier research found a positive association between participation in neighbourhood organizations and happiness. Helliwell and Putnam (2004) showed that happiness is significantly related to spending time with friends and neighbours, civic participation, and trust in neighbourhoods and the local police. As regards civic participation (membership in organizations), Dolan et al. (2008) found that belonging to organizations and engaging in volunteer work was correlated with higher levels of happiness in some studies but not others. For example, Bjørnskov (2006) found a negative association or Leung et al. (2011) reported that people who engaged in civic participation were no happier than people who did not. In relation to trust, Paldam (2000) argued that trust involves two dimensions: generalized (trust in people as a whole) and special trust (trust in known people or particular institutions). Trust is one of the defining elements of social capital. Authors such as Coleman (1988), Leung et al. (2011), Putnam, (2000) and Bjørnskov (2006) reached the same conclusion that trust is an essential element of social capital.

In their analysis, Leung et al. (2011) showed that only trust in people within one’s family was significant in happiness, but that trust in neighbours and strangers does not play a significant role. The inclusion of families in social networks can create feelings of safety and increase the availability of social support (Rözer et al., 2016). According to the literature, social networks and sense of safety support each other and positively affect perceptions of happiness (Gür et al., 2020, p.682). Layard (2005) found that married people are happier than those who are divorced, separated, widowed or who have never been married. In this line, other authors suggest the same results as Martikainen (2009), Koopmans et al. (2010) for older adults. This fact has frequently been documented by many authors who concur regarding the importance of family relationships in terms of generating happiness. Most papers state that divorced or widowed people score low on the happiness scale, regardless of neighbourhood type (Wenz, 1977).

Another fundamental aspect in determining happiness is the help received and given. In this sense, help received showed a significant negative relationship with happiness (Leung et al., 2011, p.457). In contrast, some research in public economics suggests that acts of charity and gift-giving generate a sense of warmth and help those who give to feel good about themselves (Allgood, 2011), although other works such as Leung et al. (2011) found that help given is not significant in terms of happiness.

In connection with the economic, social, and political environment other factors are personal freedom and personal values. Personal freedom refers to governance and individual rights. It is a measure of the quality of social systems (Veenhoven, 2008) that stimulate happiness. With regard to personal values, such as religion, Layard (2005) finds that the belief in a higher power is associated with happiness. Frey and Stutzer (2002) support Layard’s (2005) finding: people with religious values may be better able to cope with life’s difficulties. Moreover, certain behaviours among the religious may promote a healthier life style, thereby indirectly promoting happiness through health.

Another aspect related to the place where we live is the number of years in the neighbourhood. People who live in a particular neighbourhood for a longer time are more likely to be better connected to others in their neighbourhood (French et al., 2014; A. Ross et al., 2019). In this respect, Wenz (1977) concludes that in the case of poor neighbourhoods, people who have lived there for an intermediate number of years (2–9 years) display significantly higher happiness scores than those who have lived there for either a short or long period (p.193).

2.2 Health, Income, Work, Education

The effects of the neighbourhood on health have been studied by several authors in recent decades. For example Pérez et al. (2020) conducted a systematic review of papers exploring the impact of neighbourhood on health, and obtained evidence of the correlation between neighbourhood community life and population health. Other studies, such as those by Pickett & Wilkinson (2014) and Roy et al. (2012), find that the racial-ethnic composition and socioeconomic status of the neighbourhood predict the physical health of adults. A similar result for the younger population is obtained by Benninger et al. (2021).

Feldman and Steptoe (2004) study how neighbourhood socioeconomic status and perceptions thereof are associated with individuals' physical well-being. Other authors focus on how the physical environment of the neighbourhood (walkability, neighbourhood appearance, promoting recreational well-being…) impacts the physical well-being of residents (Know et al., 2019) or the relationship between access, quantity and types of parks and mental well-being (Wood et al. (2017). The neighbourhood’s social capital has a major impact on residents’ health and has been studied amongst the general population by authors such as Mohnen et al. (2010) or Santosa et al. (2020).

Other studies examine the neighbourhood’s effect on health from the point of view of neighbourhood health planning (Odoi et al. (2005)) and find that a knowledge of the socioeconomic characteristics of neighbourhoods is required to pinpoint their unique health needs and to help identify socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.

Self-assessed health is significantly associated with self-assessed happiness (Leyden et al., 2011), and the link between health and happiness has consistently been evidenced in the literature (Marks & Shah, 2005), whether measured subjectively or objectively. There is, however, no consensus in the literature about whether to include self-rated health as an indicator or as a predictor of subjective welfare (Lindert et al., 2015). When analysing the relationship between health and happiness, we should take into account that causality is likely to run in both directions (Crivelli & Lucchini, 2017), such that there might be a problem of reverse causality. However, many works introduce the health variable as a predictor: for example, Gerdtham and Johannesson (2001); Ross et al. (2019); Taniguchi and Potter (2016) and Weech-Maldonado et al. (2017), among others. In all cases, the authors find a positive association between happiness and health. In other works, perceived health has been seen to mediate in the relationship between perceived sufficient income and happiness. Individuals with sufficient income are more likely to have better perceived health and, as a result, are more likely to be happy (Weech-Maldonado et al., 2017).

Income, or perceived income, is an important factor when examining happiness and well-being (Dynan & Ravina, 2007). The positive association between income and happiness is one of the most robust findings in happiness research (Easterlin, 1974). The Easterlin Paradox says that happiness in a society does not increase as income rises, because the satisfaction of higher incomes is derived from having relative and not absolute incomes that are greater than those of one’s peers. For example, people in poor countries tend to be happier, net of their own income. This relates to the theory of the reference-income hypothesis, which suggests that individuals care more about how they are perceived by others, rather than the absolute level of income they have (Boyce et al., 2010). Beyond the role of income in happiness, the relationship between basic needs and happiness must be taken into account when studying the determinants of happiness in low-income settings (Camfield & Guillen-Royo, 2010; Fuentes & Rojas, 2001; Guillen-Royo et al., 2017).

As with other subjective measures, perceptions of inadequate income can offer a meaningful psychological measure of financial adequacy more than the absolute total sum (Sun et al., 2009). In general, findings concerning the impact of income in relation to neighbourhoods suggest that in the case of low-income neighbourhoods the neighbourhood attribute of economic status is more important for differences in happiness than individual economic status (Wenz, 1977). On some occasions, low mean scores in happiness for people living in low economic status neighbourhoods may be indicative of people who have been frustrated in their efforts to reach certain goals. However, living in low-income neighbourhoods has negative consequences, not only due to the presence of poverty but also because of the presence of crime, school dropout rates as well as high rates of teenage pregnancy (Firebaugh & Schroeder, 2014).

As regards work, people are reported to be a lot happier when they have secure jobs. People who have a secure job are happier than those who are unemployed or whose job is not secure (Leyden et al., 2011). The unemployed have lower scores in life satisfaction than those in employment. According to Di Tella et al. (2001), when other factors are controlled for, unemployed people are less happy than employed people. Other authors who report similar results include Dolan and Peasgood (2008) and Frey and Stutzer (2002). However, there are some exceptions to this relationship, such as Graham and Pettinato (2001) or Winkelmann (2009). This latter author found that losing a job has a negative effect on subjective welfare, although this finding is not valid for all population subgroups. For example, women and people over the age of 45 are not as negatively affected as others by the loss of their job (Winkelmann, 2009). In addition, civil status can affect what impact unemployment has on happiness (Martikainen, 2009). Furthermore, the effect of unemployment on happiness is neutralized in areas with high employment deprivation (Clark, 2003; Shields & Wheatley, 2005).

Empirical studies usually find a positive effect of education on happiness, even after controlling for level of income (Di Tella et al., 2001). However, other authors, such as Frey and Stutzer (2002, p. 5), find the effect of education on happiness to be small. Education may indirectly contribute to happiness by allowing a better adaptation to changing environments, but it also tends to raise aspiration levels. For example, Clark and Oswald (1994) said that the highly educated are more distressed than the less well educated when they are hit by unemployment. Education also has a positive effect on health, since more highly-educated people are assumed to have less unhealthy habits (Grossman, 1972). Other studies find the opposite results. After controlling for income, Clark and Oswald (1996) found that more highly-educated individuals report a lower level of satisfaction. This may be due to situations in which the individual is overqualified or has the expectation of a better job due to their qualifications.

2.3 Individual Factors

Individual factors, such as gender or age, do not appear to be significantly associated with being happy or having higher perceived health. On some occasions, these factors only explain a very small percentage of the variance of happiness. For example, Weech-Maldonado et al. (2017) found that individual factors such as gender, age and race were not significantly associated with being happy. Gender is a socio-demographic variable that has yielded inconsistent findings as it relates to happiness and well-being. A meta-analysis by Wood and Giles-Corti (2008) found a small but significant gender difference in happiness, with women being happier that men. Other studies addressing neighbourhoods, such as Taniguchi and Potter (2016), reported that the effects of neighbourhood relationships on life satisfaction and happiness are significantly greater for men in Japan. However, other studies suggest that these gender differences may have disappeared and that they may even have inverted (Stevenson & Wolfers, 2013). Wenz (1977) found that in lower income neighbourhoods the relation between gender and happiness is significant, and that men are happier than women, although the author insists that it is not just a question of roles: the neighbourhood and economic status factors affect the relationship between gender and happiness.

The effect of age on happiness is unclear. In many cases, quality of life increases with age (Gove et al., 1990), because individuals gain more insight and self-esteem. Moreover, older adults have more realistic expectations and, as a result, may cope better with life’s setbacks than younger adults are able to do (Argyle, 2001). At other times, there are many other factors related to age, such as income, work, religion, marriage or children, which can affect the feeling of well-being (Easterlin, 2003; Ellison, 1991). In the case of neighbourhoods with a low economic status, Wenz (1977) found that age is not significantly associated with happiness, except for those over 65 who tend to be less happy due to health problems and having fewer expectations. In others works, the youngest age category has significantly higher happiness scores than the older age category. For example, Gerdtham and Johannesson, (2001) found that the relation between age and happiness is U-shaped, with happiness being lowest in the 45–64 year-old age group.

3 The Educa-Sustainability Pajarillos project: Map of Happiness

The survey presented in this article forms part of the Pajarillos Educa subproject, which is part of the Pajarillos network community-based participatory project. Pajarillos Educa is a platform which brings together 12 educational communities in the district of Pajarillos (where 40 communities live together), in Valladolid, the capital of the autonomous region of Castilla y León (Spain). The various actions in the project pursue two main goals: to foster socio-educational success and local resident participation; and to merge learning and local service processes in which participants learn to work on the area’s real needs in an effort to improve the neighbourhood. The network is, therefore, collaborative and reflects social capital.

The project has three axes: Pajarillos learns (new inclusive methods and support for pupils when studying; mediation; family school and training initiatives for pupils); sustainable Pajarillos (exhibitions related to birds—ExpoAves –; the course “education for sustainability and a happy life”, map of happiness, environmental volunteering, sustainable patios -re naturalization of patios and the environment-), and Pajarillos acts (recovering disused areas next to one of the district’s primary schools where, in the evenings and at weekends, open activities are undertaken). This is the context in which the survey we now analyse was carried out (conducted between February and May 2019), in an effort to draw up a district map of happiness so as to move towards actions aimed at integration and quality of life in the area.

The Pajarillos network draws on the support of various social agents: public administrations, social organizations, cultural organizations, university and private citizens, who cooperate in the project. Such a large and varied number of members in the cooperative-platform-network evidences three things: the important social capital that exists, reflected in the survey’s results; the area’s comprehensive vision, addressing the whole of the district from the field of education, and the holistic group approach which merges knowledge, reflection, and action. The key results provided by this initial survey are being taken into consideration for action in the area and in the social environment in an attempt to improve the emotional well-being of local residents.

4 Data and Measures

4.1 Sample

The sample is made up of participants who responded to the Pajarillos Neighbourhood Sustainable Survey—Happy neighbourhood, which was carried out in 2019, as previously mentioned. The neighbourhood sample was generated using a chain referral or snowball sampling technique; that is non-probability sampling. The decision to adopt this type of sampling was taken for two reasons. The first aims to capture within the sample a hidden and hard to reach population (Atkinson and Flint (2001)). This type of sampling allowed us to access more vulnerable population groups who would not otherwise have participated in the sample. Secondly, this type of chain sampling reflects the spirit of the project in which this research is framed, wherein local resident cooperation is sought.

Furthermore, in the exploratory study carried out for one of the participating entities, no major discrepancies were found between the sample obtained in terms of marital status, level of studies, and main activity in relation to the population profile provided by the Municipal Register for the Pajarillos neighbourhood, which is the administrative register where the residents of the municipality are registered. This reports that the total number of residents in the neighbourhood in 2020 was about 18,226.

The total sample in our study compromised 594 individuals aged between 8 and 87 years old, of whom 50% were 38 years old or younger. The percentage of women in the sample is 62%. There is a greater presence of women than men in the higher age groups, and 82% of the population are under 60 years of age. The sample reflects the data on the municipal register.

As regards marital status, 48.5% stated that they lived with a partner. As for the main activity, only 30% of the sample are employed, and of the total that are employed, 30% have part-time employment. A large percentage of the population take care of household duties or of other people, and there is also a significant percentage of retirees, specifically 15% of the sample. The unemployment rate in the district is 14.83% above the average of the city in which the area is located, which has an average of 13.03% for the year in question. Furthermore, 51.5% of the population have no formal qualifications or only completed primary school studies. Surveys such as the European Quality of Life Survey carried out by Eurofound in 2016 (Ahrendt et al., 2017) show that in the case of Spain, 18% of the population have difficulty or great difficulty making ends meet. In the case of the Pajarillos district, this percentage rises to 35.81%, a figure far above the Spanish average. Given the characteristics of this neighbourhood, it is considered to have a low socio-economic profile and to display a situation of vulnerability.

4.2 Measures

In relation to the variables and instruments used for the present study, we first discuss our outcome measure, happiness, and then our explanatory variables, the main statistics of which are shown in Table 1.

4.2.1 Outcome

Happiness was assessed by people’s response to the question: “In general, how happy are you in your life?”, with answers ranging from 1 (not at all) to 10 (a lot) (self-perceived happiness). For our sample, average happiness shows a value of 7.99, with a standard deviation of 1.71 from a total of 583 observations. This average value is surprisingly higher than, for example, the average for Spain in the European Quality of Life Survey for 2016, which was 7.3. Although it must be said that comparing these averages should be approached with caution due to the different cultural contexts and realities of the target population in the two surveys, which may bias the results, especially in deprived areas. In this sense, one very interesting group of papers that deal with happiness in low income regions includes Biswas-Diener and Diener (2011) in India, Webb (2009) in Tibet, Graham and Pettinato (2002) and Mónica Guillen-Royo and Velazco (2012) in Peru, Graham and Pettinato (2002) in Russia, Guardiola et al. (2013) in Mexico, and García-Quero and Guardiola (2018) and Guardiola and García-Quero (2014) in Ecuador.

The happiness measure used in this study is related to an overall happiness judgment of what life is like for that individual (Veenhoven, 2005). As pointed out by Subramanian et al., (2005, 667), due to the multiplicity of meanings associated with happiness, this concept has been referred to as subjective well-being (Diener & Scollon, 2004).

4.2.2 Explanatory Variables

When addressing the study of which factors are significant in explaining happiness, in our analysis, we distinguish different dimensions: firstly, happiness depends on factors related directly to the neighbourhood, such as the physical environment (the presence of parks, nature, whether it is walkable …). A second group of factors is determined, at the community level, by social capital, and covers aspects such as trust in strangers, freedom, and establishing associations, while at the individual level the social capital it is linked to aspects such as family and friends. There is then a series of factors at the individual level, such as health, income, work, education. Finally, there are the socio-demographic factors, such as age and gender.

4.2.3 Expected Effects and/or Hypothesis

In view of the literature reviewed and the characteristics of the neighbourhood itself, the expected effects of this set of variables on happiness could be summed up in the following points:

In relation to the number of years in the neighbourhood, a positive effect is expected, as the variable is defined. It should be remembered that authors such as Wenz (1977) found that people who have been living in the district for an intermediate number of years feel happier. This is in contrast to those who have been living in the neighbourhood for only a few years, who are in a period of adaptation, or those who have been living in the neighbourhood for many years, who feel trapped in the neighbourhood, and have no expectations of being able to move to a better one.

Aspects such as highly perceived walkability, presence of enough parks and/or green areas are expected to have a positive influence on residents' subjective well-being, in view of the literature consulted. However, the variable relating to hearing a bird singing which, a priori should have a positive influence on individuals’ happiness, could be expected to have a negative impact in the case of the Pajarillos neighbourhood and might not even be significant due to the lack of environmental education on the part of the neighbourhood's residents. This is a matter of concern for the institutions that have already initiated environmental education programmes for the neighbourhood's population.

Variables related to social capital and social relations, such as trust in strangers, giving help or charity, as well as associationism, should have a positive influence on happiness. However, the existence of groups or collectives within the neighbourhood (Spaniards, non-Spaniards, gypsies…) with a high degree of polarisation and social tension, both between and amongst them, could lead to unexpected results, especially in the trust in strangers variable. One might also think that certain variables, such as trust in strangers, would show differences by gender.

In terms of help received, the studies consulted lead us to expect a negative impact. If we look at individual factors, having a partner, enjoying good health, having gainful employment, secondary education or higher, and freedom would be expected to positively influence our dependent variable. However, the effect of education on happiness in deprived areas is not clear. It is initially hypothesised that the majority of the population perceive no increase in happiness if they have more education, which is often due to a lack of knowledge of alternatives.

A priori, we would expect that having difficulties in making ends meet would have a negative influence on individual happiness. Nevertheless, as previously mentioned, this might not be significant, since if a large percentage of the population have difficulties in making ends meet, individuals would stop attaching importance to being in this situation, since it is felt to be something general. Much the same could be true for the impact of unemployment on happiness.

For their part, personal characteristics such as age, are expected to have an effect that is explained by a quadratic form (U-shaped), such that age and its quadratic form (age2) are incorporated into the model. A negative effect of age on happiness is to be expected with varying intensity across age groups. Although many studies show that gender is not a significant factor in explaining happiness, in our case we expect women to show lower levels of well-being than men, due to the cultural characteristics of the neighbourhood.

By way of a summary, the expected direction on happiness for each variable (+ ,- or ambivalent) is included in Table 1 with the description of the variables.

The principal statistics of the explanatory variables are also described in the following table (Table 1).

5 Econometric Model: Method and Results

The literature review has enabled us to pinpoint a series of factors to be taken into account in line with academic consensus. In this section, we aim to explore what influence these factors have on the self-perceived happiness of the local residents who make up our target sample.

In order to achieve our goal, we estimated an econometric model whose dependent variable is self-perceived happiness (self-perceived_happiness), which reflects the general happiness with their lives felt by local residents. As mentioned, this variable is expressed on a Likert scale with values ranging from 1 to 10, where 1 indicates not at all happy and 10 very happy. Given the nature of the dependent variable, we apply the Maximum Likelihood Ordered Choice Logit method, which is suited to qualitative variables with several ordered numerical responses that lack any cardinal meaning. We chose the logistic estimation which, in our case, provides the best overall results of the estimation, in addition to the best goodness of fit measures. Moreover, the Jarque–Bera test categorically rejects the hypothesis of normality of disturbances (Bera and Anil 1980).

The results of the chosen model are shown in Table 2. In order to reach these, we estimated a series of prior models, such that this model meets the highest statistical and econometric requirements. As can be seen, the explanatory variables are jointly significant for any level of significance (probability associated to the LR statistic equal to zero). The model suffers from a small problem of multicollinearity that might influence the lack of individual significance of certain variables. However, it proved necessary to maintain these variables so as not to incur in errors of omission, such that by acting as control variables they mean that the coefficients of the other variables are estimated with good properties.

Since the main aim of this work is to understand the mechanisms through which neighbourhood environments affect the subjective welfare of their residents, we commence by referring to the variables which are closely linked to the physical and social context of the neighbourhood.

5.1 Physical and Social Context of the Neighbourhood

We start with a variable which, although related to the environment in the district, has a more individual dimension—the number of years living in the neighbourhood—and we obtained results consistent with the literature addressing very poor areas. On the one hand, those who have only been living in the district a short time are likely to focus on issues concerning adaptation, such that they are still unsure as to whether their stay will be temporary. On the other hand, those who have been living in the district for a long time might feel trapped, and unable to reach their expectations of achieving a better life. These results are in line with those obtained by Wenz (1977). For the two groups of people (those who have not been there long and those who have) the number of years they have been living there has no clear effect on their happiness. Nevertheless, having lived in the district for between two and nine years (years_neighbourhood_2_9) did prove to be significant and to have a positive impact on happiness, as expected. In conclusion, people who have been living in the district for an intermediate number of years feel happier, which might point to the effect of social capital that appears in other works.

As regards walkability in the district, we also considered various ways of defining the variable based on interviewees’ responses to the question concerning the number of hours they spent going for a walk around the district at weekends. The variable which was significant is that of going for a walk around the district at weekends for four hours or more (walk_neighbourhood_4hours). As a result, people who engage in this type of activity state that they are happier, which is in line with our expected positive impact on happiness.

As for the physical environment, considering that the district has enough parks and green spaces (enough_parks_green_areas) is significant when explaining self-perceived happiness. Nevertheless, this does not mean that those who express this opinion feel happier. Contrary to what was expected, the results of the model indicate that those who do not see the need for more parks in the area and who think there are enough, feel less happy than those who believe there should be more parks. This latter group are the happiest since they might use green areas more and would like to see more of them.

According to our results, having heard a bird singing recently—that day or the previous day—(song_birds) is not a significant variable in terms of explaining happiness. For the people who live in this district, being aware that birds can be heard singing is irrelevant in terms of feeling happier or less happy. This result is consistent with the initial assumptions.

We now explain the results for the variables that are most directly related to social capital, seen as stocks of active connections among people. As seen in Sect. 2, the literature on the effect of trust in other people with regard to one’s own happiness is by no means unanimous. In any case, a distinction should be drawn between trust in strangers and trust in one’s family and friends. We now refer to the first kind of trust, as later we will deal with the relations with close groups. In our case, the results to emerge point to several striking conclusions. First, trust in strangers (trust_strangers) for the local residents of this district is a determining variable of their happiness, although only 21% of those interviewed stated that they trust strangers. Secondly, for men, trusting strangers reduces their happiness. In other words, men feel that it is not a good idea to trust strangers, possibly due to some negative experience or simply due to a fear of the unknown. Thirdly, for women, this negative effect does not exist, since the model indicates that for women, a priori, trusting strangers has no significant negative or positive effect on their feeling of happiness. The model shows how the variable of interaction between trust in strangers and gender (trust_strangers*woman) displays a coefficient which makes up for the variable of trust in strangers. Taking into account that the categories included in the model are trusting strangers and being female, the results of the two coefficients indicate that trust in strangers has a negative effect on the self-perceived happiness of men and has a virtually null effect on the self-perceived happiness of women. It is worth asking whether women establish a different kind of more open relation with those in their district and whether they are more easily able to weave networks of support and accompaniment. These result confirm the existence of gender differences in relation to trust in strangers.

As mentioned in the literature review, another aspect that defines social capital is linked to aspects such as civic engagement, community participation, voluntary work, membership of neighbourhood organizations and others, such as NGOs. The result obtained in the model is that hardly ever taking part in this kind of association (associations_almost_never) is statistically significant and has a negative effect on one’s own feeling of happiness. In this district, people who scarcely ever participate in this kind of association do not feel as happy as others. In this regard, our conclusion concurs with the results found in most works in the literature analysed and in our previous hypothesis.

We also examined what effect giving charity has on individuals’ happiness (charity). The studies cited in the references section fail to provide any unanimous conclusions on this issue. In our case, the variable related with giving charity or making donations did not prove to be significant. Moreover, it does not alter the econometric model’s goodness of fit. In other words, it is not a relevant variable. As a result, we did not include it in the model that was finally chosen.

We now look at the relations with the individual’s immediate personal environment. The variable measuring whether, if there are problems, help is available from the groups who are closest and with whom there are family or friendship ties did not emerge as significant in the model, contrary to what was expected. As mentioned previously, other studies into marginal districts have even reported a negative relation between the help received and happiness. On occasions, those who receive emotional support are not in fact happier. In our case, as pointed out, knowing that, should help be needed, support can be provided by family or friends (help_family_friends) was not significant. Nevertheless, when reviewing the data from our sample, it could be seen that, regardless of their perception concerning their own happiness, almost all of the local residents stated that they could count on this kind of support when needed. As indicated in the literature consulted, this entails an increase in the availability of social support. The literature also shows that good quality human relationships with family, friends and acquaintances tends to imply the existence of a strong personal and social protection network. As a result, local residents are aware that the area can offer a strong personal and social protection network. Consequently, in this district the mentioned variable does not discriminate with regard to the degree of self-perceived happiness.

As regards the various types of family unit, special mention should be made of that established with a live-in partner, regardless of civil status. Our results concur with all of the research carried out. As can be seen, living with a sentimental partner (partner) is fully significant in the model and has a positive effect on subjective happiness. In this specific case, the term "partner" covers a broad group that includes married couples, civil partnerships, living with a partner, and new families. People in this group of cohabitants with sentimental ties feel happier than people in the group of those who are single, separated, or divorced.

5.2 Individual Factors

We now interpret the results of the model for individuals factors. In our model, self-perceived health is a determining factor of happiness. Specifically, the variable (health), which takes a value of one when the interviewee’s response is that their health is "good or very good", is fully significant and has a clearly positive effect on subjective happiness, as we suspected. There is ample consensus in the literature with regard to this relation that can also be seen in the district subject to the present research.

On the basis of the literature consulted, a positive relationship may be inferred between considering that one has a high enough income and feeling happy. Nevertheless, the survey does not contain information about the level of income or about interviewees’ opinion with regard to whether they feel they have sufficient income. We do, however, have information concerning whether the individual has difficulty making ends meet (financial_difficulties). As mentioned, a very high percentage of local residents (24%) do have difficulty making ends meet.

As pointed out by Wenz (1977), the striking results obtained for deprived areas are that satisfaction with one’s own income depends not so much on the level of income but on a comparison with the income of others in the same area. In poorer districts, those who have low incomes tend to state that they are happier than those who, with the same income, live in middle-class areas. This theory, which has been borne out by many studies, might explain the result we obtained. Our model indicates that having difficulty making ends meet is not a significant variable for the happiness stated by those living in the district studied, a result which fits in with our initial assumptions. As regards employment status (employment_status), we studied the effect of the different labour categories (full-time workers, part-time workers, unemployed persons receiving no benefits, unemployed persons receiving benefits, pensioners, self-employed, students, and those dedicated to household tasks) on self-perceived happiness. Our results are in line with those observed in the literature for other deprived areas, where the effect of the variable unemployment on self-perceived happiness does not behave in the usual manner; in other words, reducing the feeling of happiness. The effect is neutralized by living in districts that have high unemployment rates, as is the case in hand. As a result, in our case, unemployment by itself is not significant in the model. Indeed, no single work category by itself is significant.

This does not mean that work has no effect on happiness, since a closer examination reveals that there are two distinct groups: one group comprises those in full-time employment, those who are out of work but who receive financial support, and those adults who are students. The other group is made up of five sub-groups; those who have a part-time job, those who are out of work and receive no financial support, retirees, those who take care of household duties full time, and the self-employed. This latter group was taken as the reference group in the model. The difference between these two groups does prove to be highly significant in the model and the result indicates that individuals in the first group feel happier than those in the reference group, indicating that having a full-time job, receiving financial support through unemployment benefit or being a student (employment_status) provides a greater feeling of happiness than being self-employed, taking care of the household, having a part-time job or not receiving unemployment benefit. This is hardly surprising since people who belong to this latter group probably feel less sure and less protected by their situation.

The link between education and happiness undoubtedly takes on a very particular form in deprived areas. The references section offers some of the particularities and contradictory results that have been found. In our case, none of the formal educational levels emerges as significant in the model. Nor are there any educational categories that emerge as significant. We ultimately opted for a logical clustering in two groups: the reference group encompasses those without any formal qualifications together with those who only completed primary school education. The other group includes those who completed secondary school studies and those with a degree. The fit of the model improves when including formal education although, as pointed out, the education variable (education_second_univer) is not significant, such that there is no major difference between the two groups with regard to the effect on subjective happiness. Those with a higher level of education do not feel either happier or less happy than those who have no qualifications or who only completed primary education.

Satisfaction with the freedom to do what one wants with one’s own life (personal freedom) was found to be fully significant in the model and has a positive effect on subjective happiness, as we expected.

This result is interesting because the feeling of personal freedom is a measure of the quality of social systems. Through this indicator, the individual is evaluating what contribution the social system makes to individual rights and personal development. As a result, the outcome of the model indicates that a good social system enhances the happiness of those living in this deprived district.

5.3 Socio-Demographic Factors

Finally, we interpret the results obtained for socio-demographic factors, gender and age. According to the literature, in low-income areas it is possible to obtain relations in one way or the other with regard to the link between gender and happiness, and it is also possible to obtain no relation. In our model, gender did not initially emerge as a variable that was in any way significant. Being a woman neither increases nor reduces the feeling of happiness in the district. However, as pointed out earlier, we did find an interesting result in terms of the link with the interaction between gender and trusting strangers. For women, trusting strangers has an almost null effect on their feeling of happiness, such that it neither boosts it nor diminishes it. Nevertheless, for men, the trust in strangers variable is significant, although its effect on happiness is negative, such that trusting strangers corresponds to lower subjective happiness. This result indicates that, although gender is not significant a priori, it might modify the effect that other determinants have on self-perceived happiness.

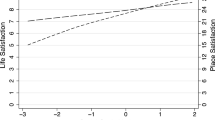

As regards the effect of age, there is no unanimity in the literature. In our case, the variable (age) was significant in its habitual quadratic form when explaining the perception of happiness. In this neighbourhood, which has a low economic status, age always has a negative effect on happiness. However, depending on the age groups, this negative effect changes in intensity. Up to the age of nearly 40, the effect is negative and worsens with each year of age; in other words, the feeling of happiness falls more sharply each year. From the age of 40 up to 60, the negative effect stabilizes: in other words, during this period, getting one year older reduces the feeling of happiness to a similar degree. Finally, after the age of 60, the negative effect gradually diminishes, such that perceived happiness worsens less each year, although it never has a positive effect.

6 Discussion and Conclusions

Certain variables (gender, formal education, difficulty making ends meet, birds’ singing, help) did not prove significant, which might be due to the homogeneity of the living conditions of the sample and to the relation with other factors that did emerge as significant, as we have seen.

Formal education is not perceived as significant, perhaps because individuals do not see any return from investing in it, or because they are unable to gain access to it. There might also be a collective belief in the theory of labelling, whereby situations of disadvantage repeat themselves and where there is enormous difficulty breaking free from these situations because of the existing structural subculture (absenteeism is seen as “normal”, there is failure at school; people do not tend to set themselves any personal educational path that leads to university, …). The school dropout rate is one of the problems the district faces and for which a solution needs to be found. The fact that this variable is not significant, as initially expected, should make us reflect on the need to design educational policies adapted to the needs of the neighbourhood and the cultural profile of its residents.

As pointed out earlier, the district evidences very high percentages of people who report difficulty making ends meet or who suffer from unemployment. As a result, designing policies aimed at reducing these rates would no doubt improve local residents’ subjective well-being. The fact that birdsong, which was included as an initial proxy to measure the level of environmental awareness and ability to observe natural phenomena, was not significant was to be expected and highlights the need to emphasise environmental education as a way of increasing local resident happiness. Fostering local resident health by providing suitable socio-health care might also be a key action in terms of enhancing their well-being. The model also clearly shows the influence of two groups of significant variables and which reinforce each other: the physical environment of the neighbourhood and social capital.

The social networks in the area (shops, bars, family, friends …) offer the possibility to interact, improve trust and also foster shared leisured. This is also consistent with the fact that the happiest people point to the need for more green spaces in the neighbourhood. Only those who really “use and inhabit public space”, not just for going to work or study but also particularly for leisure, are able to pinpoint what is missing in the urban model for a more positive experience that can lead to emotional well-being, quality of life, and happiness. Moreover, increasing trust within the neighbourhood would solve some of the problems of conflict and social polarisation suffered by its residents.

In conclusion, personal freedom, employment status, health and having a partner are strong positive predictors of happiness for local residents. Other factors, such as having lived in the neighbourhood for between two and nine years or taking a walk around the neighbourhood at weekends for four hours or more, also have a positive significant effect on happiness. We observed the negative effect of predictors such as trust in strangers, hardly ever taking part in associations, feeling there are enough parks and green areas, and age (with a changing negative effect depending on the various age groups). Surprisingly, variables such as gender, education, difficulty making ends meet and the sound of birds singing did not prove to be significant.

7 Proposals for Action, Limitations and Future Research

Many studies have evidenced how the environment can influence happiness. The way cities are designed, and in particular low socio-economic level areas, is directly linked to greater emotional well-being and everything it implies. If dwellings are not generally spacious and comfortable, if social life takes place in public spaces more than it does in other neighbourhoods, then it is essential for these spaces to provide quality of life for their residents. At present, with the disruption caused by the COVID virus, this has become even more pertinent.

This trend, both in research and in the action taken vis-à-vis public policies, can clearly be seen in the new biophilic approaches and re-connection with nature. Our findings converge with the results from approaches linked to psychology and environmental sociology. In these works, problems related to children’s health (obesity, asthma, attention deficit disorder and hyperactivity, and vitamin D deficiency) are beginning to emerge, particularly in urban areas, and which are linked to a sedentary life style and lack of contact and direct exposure to natural environments (McCurdy et al., 2010). Prominent in this regard is the importance of these neighbourhoods and specific centres (schools and the areas around them) being endowed with green public spaces as a means of creating a more appropriate level of physical, psychological and social well-being (Townsend & Weerasuriya, 2010; Wolch et al., 2014). The restorative role of nature at a psychological level (together with all of its positive impacts on observable behaviour) is clearly one of the lines to be taken into consideration in public education and urban planning policy, particularly in districts such as this one.

Aware of the need to re-naturalize our cities, the institutional framework of the European Union for the coming ten years (20–30) has made a commitment to this (Green Infrastructure Strategy; EU Green Deal and Biodiversity Strategy for 2030). Aware of all of this, the cooperation network in the Pajarillos Educa project includes an allocation of European funds from the Interreg programme for environmental improvements in schoolyards and their surrounding areas and is working on activities in the nearby nature as a key axis in formal learning.

The results of the survey support the line taken in recent years and which clearly link the four aspects of sustainability (economic, social, cultural, and environmental) and the latter’s interrelation with living well, quality of life, and subjective well-being. These approaches embrace the new conceptions of multifunctionality of happiness as a process, not a final result, based on two key axes: progress towards the concept of “One Health”, extensible from mankind and animals to the planet; and the social stratification of social well-being, pinpointing deficient areas and helping to implement policies aimed at certain underprivileged groups (Bericat., 2018; Requena Santos, 2019). Health (physical and mental) and sustainability is a strong axis which ties in with the ever-more explored and considered issue of “emotional well-being”, and with a preventive and territorialized approach pursuing greater happiness for “all”.

Improving certain aspects of the area, such as participation in organizations or creating places where people can meet and engage in social contact, and forging a walkable community, are key elements in the design of political actions since they are crucial elements in the construction of local resident well-being.

Continuing to make headway in this area is also one of the paths which may prove interesting in future lines of research. A detailed study for specific population groups, such as children or by racial groups, could certainly enrich the analysis, as would completing the quantitative study with a qualitative one.

It would also be of great interest to improve the size of the sample and the sampling system in future studies.

Change history

11 February 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00490-2

References

Ahrendt, D., Anderson, R., Dubois, H., Jungblut, J.-M., Leončikas, T., Pöntinen, L., & Sandor, E. (2017). European quality of life survey 2016: Quality of life, quality of public services, and quality of society. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2017/fourth-european-quality-of-life-survey-overview-report

Allgood, S. A. (2011). Charity, Impure Altruism, and Marginal Redistributions of Income. SSRN Electronic Journal, 0482(402). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.660181

Argyle, M. (2001). The psychology of happiness (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Atkinson, R., & Flint, J. (2001). Accessing hidden and hard-to-reach populations: Snowball research strategies. Social Research Update, 33.

Benninger, E., Schmidt-Sane, M. & Spilsbury, J.C. (2021). Conceptualizing Social Determinants of Neighborhood Health through a Youth Lens. Child Ind Res. https://doi-org.ponton.uva.es/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09849-6

Bera, J. C., & Anil, K. (1980). Efficient tests for normality, homoscedasticity and serial independence of regression residuals. Economics Letters, 6(3), 255–259.

Bericat., E. (2018). Excluidos de la felicidad La estratificación social del bienestar emocional en España. Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). Colección Monografías no 310.

Biswas-Diener, R., & Diener, E. (2011). Making the Best of a Bad Situation : Satisfaction in the Slums of Calcutta. Social Indicators Research, 55(3), 329–352.

Bjørnskov, C. (2006). The multiple facets of social capital. European Journal of Political Economy, 22(1), 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2005.05.006

Boyce, C. J., Brown, G. D. A., & Moore, S. C. (2010). Money and happiness: Rank of income, not income, affects life satisfaction. Psychological Science, 21(4), 471–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610362671

Camfield, L., & Guillen-royo, M. (2010). Wants, needs and satisfaction : A comparative study in Thailand and Bangladesh. Social Indicators Research, 96, 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9477-y

Clark, A. E. (2003). Unemployment as a social norm: Psychological evidence from panel data. Journal of Labor Economics, 21(2), 323–351. https://doi.org/10.1086/345560

Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1994). Unhappiness and unemployment. Journal of Royal Economic Society, 104(424), 648–659.

Clark, A., & Oswald, A. (1996). Satisfaction and comparison income. Journal of Public Economics, 61(3), 359–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2727(95)01564-7

Cohen, D., & Prusak, L. (2001). In Good Company: How Social Capital Makes Organizations Work, (Harvard Bu).

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95-S120.

Crivelli, L., & Lucchini, M. (2017). Health and happiness: An introduction. International Review of Economics, 64(2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-017-0279-2

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2001). Preferences over inflation and unemployment: Evidence from surveys of happiness. American Economic Review, 91(1), 335–341. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.1.335

Diener, E., & Scollon, C. N. (2004). Happiness and health. In (Ed.), : Vol. 2 (pp. 459–463). In Encyclopedia of Health and Behavior (N. B. Ande, pp. 459–463). Sage.

Dolan, P., & Peasgood, T. (2008). Measuring well-being for public policy: Preferences or experiences? In The Journal of Legal Studies. https://doi.org/10.1086/595676

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(1), 94–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2007.09.001

Dynan, K. E., & Ravina, E. (2007). Increasing income inequality, external habits, and self-reported happiness. American Economic Review, 97(2), 226–231. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.2.226

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? Some Empirical Evidence. In Nations and Households in Economic Growth (pp. 89–125). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-205050-3.50008-7

Easterlin, R. A. (2003). Explaining happiness. Series of Inaugural Articles by Members of the National Academy of Sciences Elected, 100(19), 11177–11183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-009-0125-3

Ellison, C. G. (1991). Religious involvement and subjective well-being. In Journal of Health and Social Behavior (Vol. 32, Issue 1, pp. 80–99). American Sociological Assn. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136801

Feldman, P. J., & Steptoe, A. (2004). How neighborhoods and physical functioning are related: The roles of neighborhood socioeconomic status, perceived neighborhood strain, and individual health risk factors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 27(2), 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2702_3

Firebaugh, G., & Schroeder, M. B. (2014). Does your neighbor’s income affect your happiness? NIH Public Access, 115(3), 1–25.

French, S., Wood, L., Foster, S. A., Giles-Corti, B., Frank, L., & Learnihan, V. (2014). Sense of community and its association with the neighborhood built environment. Environment and Behavior, 46(6), 677–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512469098

Frey, B., & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness and economics. Princeton University Press.

Fuentes, N., & Rojas, M. (2001). Economic theory and subjective well-being: Mexico. Social Indicators Research, 53, 289–314.

Gandelman, N., Piani, G., & Ferre, Z. (2012). Neighborhood determinants of quality of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(3), 547–563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9278-2

García-Quero, F., & Guardiola, J. (2018). Economic Poverty and Happiness in Rural Ecuador: The Importance of Buen Vivir (Living Well). Applied Research in Quality of Life, 13(4), 909–926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9566-z

Gerdtham, U. G., & Johannesson, M. (2001). The relationship between happiness, health, and socio-economic factors: Results based on Swedish microdata. Journal of Socio-Economics, 30(6), 553–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-5357(01)00118-4

Gove, W. R., Style, C. B., & Hughes, M. (1990). The Effect of Marriage on the Well-Being of Adults: A Theoretical Analysis. In Journal of Family Issues (Vol. 11, Issue 1). https://doi.org/10.1177/019251390011001002

Graham, C., & Pettinato, S. (2001). Happiness and Hardship: Opportunity and Insecurity in New Market Economies. Brookings Institution Press.

Graham, C., & Pettinato, S. (2002). Frustrated achievers: Winners, losers and subjective well-being in new market economies. Journal of Development Studies, 38(4), 100–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331322431

Grossman, M. (1972). On the Concept of Health Capital and the Demand for Health. Political Economy, 80(2), 223–255. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1830580

Guardiola, J., González-Gómez, F., García-Rubio, M. A., & Lendechy-Grajales, A. (2013). Does higher income equal higher levels of happiness in every society? The case of the Mayan people. International Journal of Social Welfare, Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00857.x

Guardiola, J., & García-Quero, F. (2014). Buen Vivir (living well) in Ecuador: Community and environmental satisfaction without household material prosperity? Ecological Economics, 107, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.07.032

Guillen-Royo, M., Guardiola, J., & Garcia-Quero, F. (2017). Sustainable development in times of economic crisis: A needs-based illustration from Granada (Spain). Journal of Cleaner Production, 150, 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.008

Guillen-Royo, Mónica., & Velazco, J. (2012). Happy villages and unhappy slums? Understanding happiness determinants in Peru. In H. Selin & S. G. Davey (Eds.), Happiness Across Cultures: Views of Happiness and Quality of Life in Non-Western Cultures (pp. 253–269). Dordrecht: Springer.

Gür, M., Murat, D., & Sezer, F. Ş. (2020). The effect of housing and neighborhood satisfaction on perception of happiness in Bursa, Turkey. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 35(2), 679–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-019-09708-5

Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2004). The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 359(1449), 1435–1446. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1522

Jeffres, L. W., Bracken, C. C., Jian, G., & Casey, M. F. (2009). The impact of third places on community quality of life. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 4(4), 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-009-9084-8

Koopmans, T. A., Geleijnse, J. M., Zitman, F. G., & Giltay, E. J. (2010). Effects of happiness on all-cause mortality during 15 years of follow-up: The Arnhem elderly study. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(1), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9127-0

Kwon, M., Pickett, A. C., Lee, Y., & Lee, S. J. (2019). Neighborhood physical environments, recreational wellbeing, and psychological health. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 14(1), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9591-6

Layard, R. (2005). Happiness: Lessons from a New Science. Penguin Press.

Leung, A., Kier, C., Fung, T., Fung, L., & Sproule, R. (2011). Searching for happiness: The importance of social capital. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(3), 443–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9208-8

Leyden, K. M. (2003). Social capital and the built environment: The importance of walkable neighborhoods. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1546–1551. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1546

Leyden, K. M., Goldberg, A., & Michelbach, P. (2011). Understanding the Pursuit of happiness in ten major cities. Urban Affairs Review, 47(6), 861–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087411403120

Lindert, J., Bain, P. A., Kubzansky, L. D., & Stein, C. (2015). Well-being measurement and the WHO health policy Health 2010: Systematic review of measurement scales. European Journal of Public Health, 25(4), 731–740. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku193

Lora, E., Powell, A., Van Praag, B. M. S., & Sanguinetti, P. (2010). The quality of life in latin American cities. In the Quality of Life in Latin American Cities. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-7837-3

Marks, N., & Shah, H. (2005). A well-being manifiesto for a flourishing society. In F. A. Huppert, N. Baylis, & B. Keverne (Eds.), The science of well-being. Oxford University Press.

Martikainen, L. (2009). The many Faces of life satisfaction among finnish young adults’. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(6), 721–737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9117-2

McCurdy, L. E., Winterbottom, K. E., Mehta, S. S., & Roberts, J. R. (2010). Using nature and outdoor activity to improve children’s health. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 40(5), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2010.02.003

Mcmillan, D. W. (2011). Sense of community, a theory not a value: A response to Nowell and Boyd. Journal of Community Psychology, 39(5), 507–519. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20439

Mohnen, S. M., Groenewegen, P. P., Völker, B., & Flap, H. (2010). Neighborhood social capital and individual health. Soc Sci Med., 72(5), 660–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.004

Odoi, A., Wray, R., & Emo, M. (2005). Inequalities in neighbourhood socioeconomic characteristics: Potential evidence-base for neighbourhood health planning. International Journal of Health Geographics, 4, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-4-20

Oldenburg, R. (1989). The great good place. Marlowe.

Paldam, M. (2000). Social capital: One or many? Definition and measurement. Journal of Economic Surveys, 14(5), 629–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6419.00127

Pérez, E., Braën, C., Boyer, G., Mercille, G., Rehany, É., Deslauriers, V., Bilodeau, A., & Potvin, L. (2020). Neighbourhood community life and health: A systematic review of reviews. Health & Place, 61, 102238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102238

Pickett, K. E., & Wilkinson, R. G. (2014). Income inequality and health: a causal review. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 316–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.031

Putnam, R. D. (2000). (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster.

Requena Santos, F. (2019). Opinión pública y felicidad. Las bases sociales y políticas del bienestar subjetivo. Panorama Social, 30, 183–198.

Rojas, M. (2005). A conceptual-referent theory of happiness: Heterogeneity and its consequences. Social Indicators Research, 74(2), 261–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-4643-8

Ross, A., Talmage, C. A., & Searle, M. (2019). Toward a Flourishing Neighborhood: The Association of Happiness and Sense of Community. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 14(5), 1333–1352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9656-6

Ross, C. E., & Mirowsky, J. (2001). Neighborhood Disadvantage, Disorder, and Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(3), 258–276. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090214

Roy, A. L., Hughes, D., & Yoshikawa, H. (2012). Exploring Neighborhood Effects on Health and Life Satisfaction: Disentangling Neighborhood Racial Density and Neighborhood Income. Race and Social Problems, 4, 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-012-9079-1

Rözer, J., Mollenhorst, G., & Poortman, A. R. (2016). Family and Friends: Which Types of Personal Relationships Go Together in a Network? Social Indicators Research, 127(2), 809–826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0987-5

Sallis, J. F., Kerr, J., Carlson, J. A., Norman, G. J., Saelens, B. E., Durant, N., & Ainsworth, B. E. (2010). Evaluating a brief self-report measure of neighborhood environments for physical activity research and surveillance: Physical Activity Neighborhood Environment Scale (PANES). Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 7(4), 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.7.4.533

Santosa A, Ng N, Zetterberg L, & Eriksson M. (2020): Social Capital as a Resource for the Planning and Design of Socially Sustainable and Health Promoting Neighborhoods-A Mixed Method Study. Public Health, 8. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.581078

Shields, M., & Wheatley, S. (2005). Exploring the economic and social determinants of psychological well-being and perceived social support in England. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society), 168(3), 513–537.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2013). Subjective and Objective Indicators of Racial Progress The civil rights movement revolutionized the lives of blacks in the United. National Bureau of Economic Research, w18916(June).

Subramanian, S. V., Kim, D., & Kawachi, I. (2005). Covariation in the socioeconomic determinants of self rated health and happiness: A multivariate multilevel analysis of individuals and communities in the USA. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59(8), 664–669. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.025742

Sun, F., Hilgeman, M. M., Durkin, D. W., Allen, R. S., & Burgio, L. D. (2009). Perceived income inadequacy as a predictor of psychological distress in Alzheimer’s caregivers. In Psychology and Aging (Vol. 24, Issue 1, pp. 177–183). https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014760

Taniguchi, H., & Potter, D. A. (2016). Who are your neighbors? Neighbor relationships and subjective well-being in Japan. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 11(4), 1425–1443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-015-9445-4

Townsend, M., & Weerasuriya, R. (2010). Beyond Blue to Green: The benefits of contact with nature for mental health and well-being. Beyond Blue Limited. https://www.deakin.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/310747/Beyond-Blue-To-Green-Literature-Review.pdf

Veenhoven, R. (2005). Happiness in Nations. Subjective appreciation of life in 56 nations 1946–1992. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 351–355.

Veenhoven, R. (2008). Healthy happiness: Effects of happiness on physical health and the consequences for preventive health care. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(3), 449–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9042-1

Webb, D. (2009). Subjective wellbeing on the Tibetan plateau: An exploratory investigation. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(6), 753–768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9120-7

Weech-Maldonado, R., Miller, M. J., & Lord, J. C. (2017). The relationships among socio-demographics, perceived health, and happiness. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 12(2), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9517-8

Wenz, F. V. (1977). Neighborhood type, social disequilibrium, and happiness. Psychiatric Quarterly, 49(3), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01115314