Abstract

This study examines two questions relating to the banking market structure. First, does the banking market structure influence banks’ decisions to originate new single-family home mortgages? Second, does the banking market concentration affect mortgage default risks? Using a two-stage approach with the inputs from two data sources on the banking market in the US and mortgages in non-agency securitization pools for the period from 1999 to 2008, we find that banks operating in the markets with a low entry barrier (efficient banks) increase credit supply, while banks possessing market power restrict credit supply to the mortgage markets. Banks with market power originate loans that have lower default risk compared to loans originated by banks in the competitive markets. Efficient banks use mortgage technology indiscriminately to increase credit supply even at the expense of lowering credit quality (increasing default risks). We show that the effects of banking market structure are not correlated with legislation risks and population size in the markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The passage of the Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act (IBBEA) of 1994 has mandatorily removed geographical branching restrictions in all MSAs in the US.

Mian and Sufi (2009) define the subprime zip-codes as counties that have a high concentration of high risk loans with a FICO score of below 660.

Please refer to the Appendix for the technical details for the derivations of the HHI and the PR H-statistics.

For sample mortgages with a foreclosure record earlier, and the earlier date was not recorded in the 24-month window, the first date of the 24-month window is used as the truncated foreclosure date. This approach biases downward the foreclosure duration measure, and we need stronger statistical power to reject the hypotheses.

The 25th percentile of the distribution of the FICO score in our total sample is cut off at 634. However, we adopt a lower FICO of 620 as the cutoff for high risk mortgages, which is more consistent with the definition used by researchers (Agarwal et al. 2012a; Keys et al. 2010). The lower cutoff sets a higher upper bound for us to reject the hypothesis.

The economic theory of monopoly holds on the assumptions that there is no substitute of credit supply, no barriers of entry and exit, and a single credit product is provided.

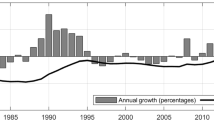

The relative house price variable is represented by the housing price growth rate computed from the state-level Housing Price Index of the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), [Pt / Po].

The fixed zip-code effect was suggested by the anonymous referees to control for possible error clustering at the zip-code level, and other unobserved variations in local market behavior across different zip-code counties. The models with zip-code locational fixed effect significantly improve the model R2. The R2 for models without the fixed zip-code effects range between 0.5706 and 0.5714.

The above results that explain the effects of banking market structure on credit supply are independent of interest rate effects, because the average yearly correlations between interest rate and HHI and PR-H are relatively low at 0.015 and – 0.058, respectively.

In judicial foreclosure states, court orders are required to start foreclosure proceedings. It usually begins by a lender filing a notice (complaint) in public land records to seek a foreclosure claim on a subject property against non-payments. However, in non-judicial foreclosures states, there is no court intervention in the foreclosure proceedings. The lender’s attorney will mail default letters directly to delinquent borrowers.

If state laws provide for deficiency judgments against recourse loans, lenders could hold individual borrowers liable for short-fall in debt, if the value of a property is insufficient to cover the loan balance at the point when a foreclosure proceeding is initiated.

References

Agarwal S, Chang Y, Yavas A (2012a) Adverse selection in mortgage securization. J Financ Econ 105(3):640–660

Agarwal S, Ambrose B, Chomsisengphet S, Sanders A (2012b) The neighbor's mortgage: does living in a subprime neighborhood impact your probability of default? Real Estate Econ 40(1):1–22

Ambrose B, Pennington-Cross A (2000) Local economic risk factors and the primary and secondary mortgage markets. Reg Sci Urban Econ 30:683–701

Bailey EE, Baumol WJ (1983) Deregulation and the theory of contestable markets. Yale J on Reg 1:111–137

Beck T, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Levine R (2006) Bank concentration, competition and crises: first results. J Bank Financ 30:1581–1603

Beck T, Levine R, Levkov A (2010) Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J Financ 65(5):1637–1667

Behr P, Schmidt RH, Xie R (2010) Market structure, capital regulation and bank risk taking. J Financ Serv Res 37:131–158

Berger AN (1995) The profit-structure relationship in banking - tests of market-power and efficient-structure hypotheses. J Money Credit Bank 27(2):404–431

Bresnahan TF (1982) The oligopoly solution concept is identified. Econ Lett 10:87-92.

Calhoun C, Deng Y (2002) A dynamic analysis of adjustable- and fixed-rate mortgage termination. J Real Estate Financ Econ 24(1):9–33

Calice G, Ioannidis C, Williams J (2012) Credit derivatives and the default risk of large complex financial insitutions. J Financ Serv Res 42:85–107

Claessens S, Laeven L (2004) What drives bank competition? Some international evidence. J Money, Credit, Bank 36(3):563–583

Dell'Ariccia G, Igan D, Laeven L (2008) Credit booms and lending standards: evidence from the subprime mortgage market. International Monetary Fund, Working Paper

Deng Y (1997) Mortgage termination: an empirical hazard model with a stochastic term structure. J Real Estate Financ Econ 14:309–331

Deng Y, Quigley J, Van Order R (2000) Mortgage terminations, heterogeneity and the exercise of mortgage options. Econometrica 68:275–307

DeYoung R, Klier T, McMillen DP (2004) The changing geography of the U.S. banking industry. Ind Geogr 2(1):29–48

Dick AA, Lehnert A (2010) Personal bankruptcy and credit market competition. J Financ 65(2):655–686

Düllmann K, Masschelein N (2007) A tractable model to measure sector concentration risk in credit portfolios. J Financ Serv Res 32:55–79

Durkin TA, Elliehausen GE (1998) The cost structure of the consumer finance industry. J Financ Serv Res 13(1):71–86

Gan J (2004) Banking market structure and financial stability: evidence from the Texas real estate crisis in the 1980s. J Financ Econ 73:567–601

Gan J, Riddiough T (2008) Monopoly and information advantage in the residential mortgage market. Rev Financ Stud 21:2677–2703

Gerardi KS, Rosen HS, Willen PS (2010). The Impact of Derugulation and Financial Innovation on Consumers: The Case of the Mortgage Market. J Finance 65:333-360

Gilbert RA (1984) Bank market structure and competition: a survey. J Money Credit Bank 16(4/2):617–645

Hakenes H, Schnabel I (2010) Credit risk transfer and bank competition. J Financ Intermed 19:308–332

Herring RJ, Santomero AM (1990) The corporate structure of financial conglomerates. J Financ Serv Res 4(4):471–497

Keys B, Mukherjee T, Seru A, Vig V (2010) Did securitization lead to lax screening? Evidence from subprime loans. Q J Econ 125:307–362

Lau LJ (1982) On identifying the degree of competitiveness from industry price and output data. Econ Lett 10:93–99

McMillan DG, McMillan FJ (2016) US bank market structure: evolving nature and implications. J Financ Serv Res

Mercieca S, Shaeck K, Wolfe S (2009) Bank market structure, competition, and SME financing relationships in European regions. J Financ Serv Res 36:137–155

Mian A, Sufi A (2009) The consequences of mortgage credit expansion: evidence from the US mortgage default crisis. Q J Econ 124:1449–1496 50:187–210

Mocetti S, Pagnini M, Sette E (2017) Information technology and banking organiztion. J Financ Serv Res 51:313–338

Neuberger D, Padergnana M, Räthke-Döppner S (2008) Concentration of banking relationships in Switzerland: the result of firm structure or banking market structure? J Financ Serv Res 33:101–126

Ogura Y (2010) Interbank competition and information production: evidence from the interest rate difference. J Financ Intermed 19:279–304

Panzar J, Rosse J (1982) Structure, conduct, and comparative statistics. Bell Laboratories Economic Discussion Paper, Bell Telephone Laboratories, Inc.

Panzar J, Rosse J (1987) Testing for "monopoly" equilibrium. J Ind Econ 35:443–456

Pilloff SJ (1999) Does the presence of big banks influence competition in local markets? J Financ Serv Res 15:159–177

Rothschild M, Stiglitz J (1976) Equilibrium in competitive insurance markets: an essay on the economics of imperfect information. Q J Econ 90:629–649

Scharfstein DS, Sunderam A (2015) Market Power in Mortgage Lending and the Transmission of Monetary Policy. Harvard University, Mimeo

Stiglitz J, Weiss A (1981) Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. Am Econ Rev 71:393–410

Whalen G (2000) Trends in organizational form and their relationship to performance: the case of foreign securities subsidiaries of U.S. banking organization. J Financ Serv Res 17(1):181–218

Yildirim HS, Mohanty SK (2010) Geographic deregulation and competition in the us banking industry. Financ Markets Institutions Instruments 19:63–94

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Brent W. Ambrose, Yongheng Deng, Yuming Fu, David C. Ling, Wenlan Qian, Timothy Riddiough, Anthony B. Sanders, Geoffrey K. Turnbull, Nancy Wallace and others for their valuable comments and suggestions. Appreciations are also given to other participants and discussants in 2011-NUS-IRES Research Symposium on Information Institutions and Governance in Real Estate Markets, Singapore and Global Chinese Real Estate Congress.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Measures of contestability and concentration of banking markets

Appendix: Measures of contestability and concentration of banking markets

1.1 Panzar and Rosse (1982, 1987) index (PR-H)

The PR-H statistics proposed by Panzar and Rosse (1982, 1987) is estimated by first regressing the logarithm of total interest income, π, against annual expense on funds, F, personal expense, PE, and physical capital expense that include furniture, fixture, equipment and auto, PCE, as follows:

The regression (7) is separately estimated (560 regressions) for the 50 US states and 6 other territories / islands (American Samoa (AS), Federated States of Micronesia (FM), Guam (GU), Puerto Rico (PR), Rhode Island (RI) and Virgin Islands (VI)), each year for the sample periods from 1999 to 2008, to derive at the (56 × 10) matrix of regression coefficients, [β1, β2, β3]. The state-year PR-H statistics are then computed as the sum of the three input factor elasticity:

A bank with a high PR-H statistic is known to operate efficiently in producing loan services at the lowest marginal costs.

1.2 Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI)

Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is a widely used measurement for market concentration. In computing HHI, we first determine the market share of each bank in a market sorted by state and by year:

where ρi is the market share of a sample bank in a state j. Ei is the total equity value of the bank. \( \sum \limits_{\mathrm{i}\in \mathrm{j}}{\mathrm{E}}_{\mathrm{i}} \) is the cumulative equity value of all bank i in a state j.

The squared market share of each banks in state j is added up to give the HHI value, which ranges from close to zero to a large number:

where n is the total number of banks in the market segment j, and the total number of banks could be limited by a ceiling of 50 banks. A small HHI value indicates that a market is less concentrated; and a large HHI value indicates that a market is highly concentrated. If there is only one bank in the market, the value would be one. When the value approaches to zero, the market is perfectly competitive.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, B., Shilling, J.D. & Sing, T.F. Large Banks and Efficient Banks: how Do they Influence Credit Supply and Default Risk?. J Financ Serv Res 57, 1–28 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-018-0300-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-018-0300-2