Abstract

The purpose of this study was to look into how Information and Communication Technology (ICT) is used in teaching English language from the point-of-view of English language teachers in Palestine. A quantitative approach was employed to collect data from 780 language school teachers from 260 schools who participated in a course project utilizing ICT in English as a Foreign Language teaching (TEFL). These participants responded to a questionnaire survey about the effects of the Covid-19 epidemic on language education and how they dealt with these. We statistically analysed the responses through four domains: the use of ICT in students’ lives; the use of ICT in education generally; the use of ICT to support learning and teaching in EFL; and teachers’ perceived skills for using ICT in education. Results indicated that English language teachers in Palestinian public schools believed that ICT has clear potential to support the learning of English, but that there remain barriers to its implementation. Teachers feel equipped to use ICT but would like to see a greater emphasis on training in order to maximise their teaching.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Information and Communication Technology (ICT) is generally defined as the implementation of different applications and devices so as to help in the support of the educational aims that appeal to the needs of students (Kinsella et al., 2021). The proliferation of ICT in language education has evoked a lot of research studies in the field examining its effectiveness for students and teachers (Comi et al., 2017; Ghavifekr & Rosdy, 2015). It is clear that “the last decade has witnessed increasing integration of various forms of technology in schools” (Qaddumi et al., 2021:1), and this is showing no signs of stopping. It might be argued that this development has impacted every part of our educational system, including language instruction. Its success was ultimately dependent on instructors’ confidence in its classroom, despite its primary purpose of serving as a tool for teachers and textbook designers (Bashir, 1988). These days, the use of ICT in the service of language education in schools cannot be avoided. Schools need teachers who are able to keep up with the latest developments in teaching and learning, highlighting the growing need for a skilled workforce. There is a growing worldwide trend of, and interest in, the integration of digital skills into language education (see, e.g., Reinders, Lai & Sundqvist, 2022). International and regional conferences have highlighted the need for the continual advancement of the employment of ICT in the educational curricula at all levels ( Cakici, 2016; Haldoraiet al.,2020 Qaddumi et al., 2021). The need for changes in educational curriculum that use ICT in the service of education was emphasized at the First International Conference on Technical and Vocational Education, which UNESCO convened in Berlin, Germany in 1987 (Qaddumi et al., 2021). In recent years, ICT has increasingly been used in schools and colleges to help teaching and learning, but during the pandemic, ICT tools were the easiest and most available solutions in many contexts to cope with the lockdowns of schools and universities (Ayoub & Ahmad, 2020; Traxler et al., 2020; Smith & Traxler, 2022).

One of the key elements that enable the quick transfer of knowledge to students at large is the use of ICT in English education. This study adds to and supports the empirical research that has been done thus far on the effective use of ICT in English language instruction, which aims to help the Ministry of Education achieve its objectives. Anecdotal evidence from across Palestine and the personal experience of the researchers indicates that, whilst Palestinian language teachers espouse the widening use of ICT to support language learning, there is only sporadic evidence of this taking place, and that this is based on personal competence and confidence in ICT usage rather than the outcome of institutional or governmental initiatives.

Digging into English language teachers’ actual ideas on the use of ICT and integration in English language teaching was a crucial step in this research that set it apart from earlier studies. In relation to our first specific goal, which is to explain teachers’ viewpoints and beliefs about the use of technology to enhance language teaching and learning, we sought to discover English language teachers’ beliefs about the significance of ICT in the teaching-learning environment: for example, whether English language teachers consider technological mastery to be an essential or inessential skill for success in both the professional and personal realms.

The following research questions served as the basis for our inquiry, leading the researchers to investigate the reality of teachers’ perceptions about the integration of ICT in language instruction:

-

(1)

What are Palestinian English language in-service teachers’ beliefs about the uses of ICT and its integration in English language teaching?

-

(2)

Do Palestinian English language in-service teachers’ gender or professional experiences influence their beliefs about ICT integration in English language teaching?

There are six sections in the article. The first is an introduction, followed by a review of the literature on the use of ICT in teaching EFL and the variables that motivate teachers to use it, and then the questions are presented. The later sections present the research methodology, an analysis and discussion of the results and the study’s conclusions and recommendations are then given.

2 Teachers’ beliefs about ICT integration in teaching EFL

Professional development is always a flexible aspect of teachers’ teaching and learning process in order to support teachers to engage and teach effectively (Lan & Lam, 2020; Maasepp & Bobis, 2014) note that CPD for teachers should include the developmental evaluation of teachers’ beliefs. They categorise teachers’ beliefs as either transmissive or constructivist beliefs, and report that teachers who are described with transmissive beliefs tend to dominate their classrooms; they are the centre of their class activities so as to deliver the content and transmit knowledge. However, teachers who are constructivist in their beliefs are guides, friends and facilitators: they help and support the learners to construct their knowledge (Garrison, 1993; Fraser & Ikoma, 2015; Smith, 2016, 2017). Further studies indicate that educators have mainly positive beliefs about the integration of ICT into teaching and learning (Laumer & Maier, 2021).

Teachers must have a clear personal epistemology and think that certain teaching methods are effective before they can engage in any pedagogical practice (Brownlee et al., 2011; Smith, 2016). However, it is crucial to remember that attitudes and behaviors are not always in line with one another. Teachers are capable of engaging in instructional practices that are at odds with their professed epistemologies (Many et al., 2002; cf. Vacc and Bright, 1999; Wilson and Cooney, 2002). Feiman-Nemser et al. (1987) and Fosnot (1989) pointed out that teachers’ intents and desired teaching methods may not be appropriate for a setting that bears little to no similarity to the envisioned circumstance and professional experience for which the original intentions were established (Liljedahl, 2008).

There have been numerous studies on teachers’ beliefs around the integration of ICT into language education systems (see, e.g., Qaddumi et al.,, 2021). For instance, Rababah (2020) investigated the difficulties and problems faced by English language learners when utilizing online learning resources when schools were closed. Some of these obstacles and challenges include teachers’ competence and ICT skills et, their confidence in using ICT tools, the training of teachers, poor or missing software, teacher attitudes, digital (and actual) poverty, poor infrastructure, and traditional education systems that favour in-class over online teaching, and inflexible curricula (Khatoony & Nezhadmehr, 2020; Nugroho & Mutiaraningrum, 2020; Supriadi et al., , 2020; Tandon, 2020). Despite these challenges, a host of studies have revealed that language teachers have positive perceptions towards integrating ICT because of its effectiveness in education and language teaching (Adarkwah, 2021; Bazimaziki, 2020; Ferdig et al., 2020; Fitri & Putro, 2021; Gandhi, Hethesia & Monica, 2020; Kundu & Dey, 2020; Ntshwarang, Malinga & Losike-Sedimo, 2021; van der Spoel et al., 2020). Ali (2020) found that there has been a near-global adoption of ICT into teaching at schools and universities. It is clear that Language teachers need to follow suit.

Numerous research projects have been carried out abroad on EFL university lecturers and schoolteachers and the integration of ICT into their teaching (e.g. Cahyadi, 2020; Hismanoglu, 2012; Rahiem, 2020).Researchers examining EFL teachers’ perceptions of using and integrating CALL and ICT into their classrooms at schools and higher education institutions report that this integration has positive effects and improves motivation in learners (Abduh, 2021; Bond, 2020; Cicha et al., 2021; Rahim & Chandran, 2021; Rakıcıoğlu-Söylemez & Akayoğlu, 2019). Researching teaching a writing skills class online in Indonesia, Aniq et al. (2021) found that utilizing different ICT and methodological tools such as familiar smartphone apps, engaging content-based curriculum and applying student-oriented teaching method were of a great positive impact on students. Similarly, Mokh et al. (2021) studied Palestinian language teachers’ beliefs around technostress when teaching online, and found that teachers seem to be comfortable with both styles of teaching: face to face and virtual. According to Subekti (2021), who looked into pre-service English teachers’ opinions on the application and integration of ICT in online learning, they believed that synchronous and asynchronous teaching methods should be used in conjunction was important for best practice, as using both eased the burden on learners and boosted their learning effectiveness.

3 Factors influencing teachers’ beliefs about using ICT

The public schools, institutions and universities governed by the Palestinian Ministry of Education and Higher Education have not ignored these developments in the use of ICT. The use of ICT in the service of language education has been of great interest (Qaddumi et al., 2021; Lepp et al., 2021) studied factors related to teaching beliefs around ICT integration and found these beliefs were influenced by many factors such as the availability of digital tools, personal ability to use ICT, teachers’ and students’ attitudes, ICT competences, teachers’ self-efficacy, teaching professional experiences, teaching load and demographic variables (cf. Almanthari, Maulina & Bruce, 2020).According to Adarkwah (2021) and Lepp et al. (2021), teachers in low-income countries are hesitant to integrate ICT in their teaching as a result of poor infrastructure, network challenges and electricity. A lack of appropriate e-materials, learners’ distraction while learning online, and learners’ demotivation are also cited as factors that influence teachers’ beliefs as to the benefits of integrating ICT in teaching by Khatoony & Nezhadmehr (2020). Carvalho, Casado & Delgado (2020) further found that teachers’ competence in ICT is considered as an important indicator to integrate ICT in teaching.

4 ICT in the service of teaching EFL

Utilizing ICT to aid in the teaching of English as a foreign language is one way of developing in-service teachers’ abilities and teaching performance (Kimav & Aydin, 2020; Rizkiani, 2021). New technical implications and opportunities for teaching English are growing globally and at all levels of school with the advent of the digital era and the pandemic-enforced lockdowns (Kimav & Aydin, 2020; Beardsley et al., 2021). In order to improve the teaching of all school and university subjects across the curriculum stages, the Palestinian Ministry of Education and Higher Education has thus decided to incorporate modern technology into its curricula and educational plans (Qaddumi et al., 2021). This attitude is the driving force behind the Ministry’s new strategic planning and new policy to develop pre-service and in-service teachers to effectively interact with the digital environment ( Khatoony & Nezhadmehr, 2020) and to meet the challenges (Qaddumi et al., 2021; Ryn & Sandaran, 2020). Tamah, Triwidayati & Utami, (2020) and Habibi, Yusop & Razak (2020) found that ICT used in the service of language learning and teaching can bring wide-ranging benefits. According to Ryn & Sandaran (2020) and Wen & Kim Hua (2020), these could include access to online resources; providing immediate feedback to the language learners; better retention; and achievement in language learning (Marchlik et al., 2021);language learners’ acquisition of language skills and computer literacy(Moorhouse & Beaumont, 2020);keeping language learning process progressing (Al-Shammari, 2020); learning online innovative positive digital skills (Maican & Cocoradă, 2021; Arono et al., 2021); developing problem-solving skills (Korkmaz et al., 2020); and reducing the burden on the teachers (Qaddumi et al., 2021). Particularly in higher education, where it has created ICT initiatives to help teachers in their homes, the Palestinian Ministry of Education and Higher Education has been successful in reviving and deploying ICT in the service of education across the many educational stages (Affouneh et al., 2021; Nabulsi et al., 2021; Subekti, 2021), which was of material benefit during the enforced lockdowns of Covid(Mustafa & Abbas, 2021; Samara, 2021; Subaih, 0221).

The above works adequately demonstrate the significance of determining teachers’ attitudes on the incorporation of ICT in language teaching and the variables affecting such perspectives. This interest was piqued by our own professional experiences in Palestinian classrooms. Conversations with teachers over time suggested that they hoped to incorporate ICT into language instruction during the pandemic’s transitional phase, but day-to-day interactions and observations revealed little evidence of this being actualised. This research sought to assess teachers’ attitudes toward ICT integration in language teaching and comprehending EFL teachers’ viewpoints around what this would look like in practice.

5 Method

We concluded that a descriptive approach was most suitable for such a large-scale sample to uncover the beliefs of English language teachers about the integration of ICT in their language teaching and what factors contribute to influence their beliefs. This approach is appropriate because the problem of teachers’ integration of ICT in language teaching has been neither determined by the researchers in Palestine nor yet clearly identified.

The researchers therefore used a descriptive approach for data collection. To get the necessary data from the sampled English language teachers, questionnaire surveys were used. Table 1 displays the sample’s specifics. Following the pandemic shutdown, teachers were asked to share their opinions by completing online survey forms.

5.1 Participants

According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (2019/2020), there are 899 schools in the north of Palestine. During the academic year in which the survey was done, 2020–21, 185,804 students attended these schools online and were instructed by 2,697 English language teachers. The study’s sample therefore draws on a purposive sampling to select 780 participants (21%) of the region’s language school teacher population.

5.2 Data collection

5.2.1 Survey questionnaire

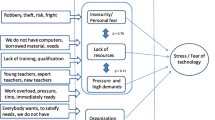

To get the needed information from the sampled English language teachers, the researchers employed an online questionnaire with questions of the Likert Scale variety. This was brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic-related closures. The questionnaire, which measured teachers’ opinions on the use of ICT in language instruction, had 32 items spread across four areas. The researchers drew on previous studies to form the survey questionnaire. Figure 1 (below) gives a list of the literature we drew on.

Figure 1 demonstrates the literature on which the items and domains were designed. We particularly drew on the literature and studies conducted by Chamorro & Rey (2013), Ryn & Sandaran (2020); and Zhang (2020) to solicit teachers’ beliefs about the integration of ICT into English language teaching and the factors which influence these beliefs. SPSS software was used to analyze the quantitative data. The validity check of the survey questionnaire was carried out in two ways. The survey questionnaire was sent to referees, a number of experts in the field, who revised it. Internal consistency validity, which shows the relationship between each item’s degree and the sum of the domains’ degrees, was used to establish a second level of validity. Clearly, each item and the sum of the domains’ degrees are correlated in a statistically meaningful way. The entire degree of the scale is statistically significant at the level of 0.01 and all domains are interrelated. The degree of each domain and the scale’s overall degree were strongly correlated with one another. Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficient for the questionnaire was determined as 0.85 to further illustrate its reliability.

6 Results and discussion

6.1 In-Service Teachers’ beliefs about ICT integration in EFL

In order to get a sense of what EFL teachers thought about ICT integration in EFL instruction, a survey of EFL teachers was conducted. Table 1 shows the results.

The following section answers question one of this study. The question states what are the English language teachers’ beliefs about the use of ICT and integration in English language teaching?

The information in Table 1 shows that English language instructors’ attitudes about the use and integration of technology in language instruction were moderate across all categories (M = 3.61). The highest domain is the Use of Information and Communications Technology in Students’ Lives (M = 4.20).This domain was the highest in rank which means that teachers believe that technological advancements have a major influenced on students. Teachers believed that ICT can help students succeed in their future jobs. They also believe that technology was not given enough attention as a skill to allow students to succeed in professional fields. A part of this could be cultural barriers to the integration of technology in people’s daily life although, as teachers believed, It has assisted in redefining conventional ideas about participation, communication, and human engagement, and the development of ideas, although they also reported that students relied too much on technology to get information and that it was being used more in business than in any other field. The majority of respondents (84%) believed that ICT was used in students’ lives. Then, the second domain was The use of ICT in Education Today (M = 3.61) where a moderate percentage (72.2%) of teachers believed that they felt innovation was crucial to be included in EFL classes; they thought ICT required educators to start teaching in a different way; it is essential to integrate ICT into teaching EFL as it us currently only superficial; and that EFL teachers only conceptualise the use of ICT as using search engines and commercial websites. However, 52% believed ICT did not adequately support learning in EFL classes. The third was The Use of ICT and My Learning and Teaching Goals in EFL Class (M = 3.32) where its percentage was 66.4%. Teachers believed they would be good designers of their materials and EFL activities with ICT; the fact that the Ministry of Education in Palestine consistently offers ICT courses for teachers meant that they had to have a lot of skills in order to adapt the new ICT scales to their demands for learning and teaching. Teachers gained skills more through professional development training than by themselves. They became high-level users of ICT in EFL class as the classes nowadays are a part of the global education. Finally came the domain My Skills for Using ICT in Education (M = 3.29) and a percentage of 65.8%. As for the beliefs of English language teachers towards the use and integration of technology in language teaching for each domain of study, the mathematical averages, we break down each domain in more detail below.

The total score of this domain was high. Table 2 indicates that the degree English teachers believe about the implementation of ICT in students’ lives was high (M = 4.20, 84.0%). It was very obvious that the highest degree of responses on this domain was ICT abilities can help students succeed in their future jobs (M = 4.39, 87.8%). Teachers believed that ICT skills were very critical to succeed in future workplace. So ICT, they believed, should be given much attention. However, the item I feel ICT is being used more in business than in any other field received the lowest degree of responses in this domain compared with other items in the domain (M = 4.06, 81.2%). This showed that the teachers were convinced that ICT could be implemented in other fields rather than business. Teachers believed that ICT redefined conventional notions of social interaction, communication, participation, and idea generation. They felt that people used technology for information far too much. These results are consistent with Alismail & McGuire (2015), Aničićet al. (2016), Ayat et al. (2020), Bakkum et al. (2022), Barlott et al. (2020), Cesco et al. (2021), Gómez et al. (2021), Hussin (2018), and Lucas et al. (2022) amongst others.

The degree of English instructors’ beliefs is shown in Table 3 about the use of ICT in education today was moderate (M = 3.61, 72.2%). Item 9 (M = 4.50, 90.0%) in this domain shows the clear belief that creativity is an important part of integrating ICT in language class. However, item 10 (M = 2.68, 53.6%) clarified that teachers only believed ICT promoted learning in EFL class to a low extent, as this item received the lowest degree. It can be inferred from Table 3 above that teachers encouraged the use of ICT in their classes and they were confident that ICT help them feel creative. Accordingly, ICT should not be integrated superficially and should not be just related to searching information and commercial web pages.

Table 4 shows that the degree of the beliefs of English teachers about their skills for using ICT in education was moderate (M = 3.29, 65.8%). Item 18 scored the highest degree (M = 4.18, 83.6%). Teachers believed that the use ICT can help students learn English language well. This was very clear in their responses to item 18 which implies that they did not use technology integrated activities just because they were established in their course guidelines. This item received the lowest degree (M = 2.17, 43.4%). Teachers felt they can deal with materials and EFL activities with ICT. They believe they have gained a lot of abilities in order to modify the new ICT scales to fit their demands for teaching and learning. They were confident they use ICT a lot as they received training provided by The Ministry of Education and Higher Education. Such training courses on ICT integration in the teaching process helped them a lot to gain self-confidence (Aydin, 2013; Mirzajani et al., 2016).

Table 5 demonstrates that English instructors’ attitudes on the use of ICT and my educational objectives in EFL classes were moderate (M = 3.32, 66.4%). The highest response was on item 32 where the mean was (M = 4.39) and its percentage was 87.8%. This indicated that teachers’ use of technology was mainly to reinforce any or all of the four skills of students’ language. Teachers believe that the use of ICT was to promote collaborative learning in class as well as learning the language as they feel technology was useful to comprehend topics and develop the four skills more easily. Teachers believed that ICT implementation in teaching des not only help motivate students in the classes but also facilitates teaching and learning processes. Very few teachers believed that using ICT in their classes would help students improve their language skills. A fair proportion of teachers believed that employing technology-based activities in the classroom was difficult for students to develop some abilities and took a lot of time.

The results of the above tables demonstrate that the majority of teachers believed that mastering ICT abilities can help students succeed in their future jobs; and that there should be more focus on teachers’ professional development. A large number of teachers suggested that ICT integration in students’ lives improves their social interaction, means of communication and participation. This may be because expressing feelings and social engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic breakout may have been difficult for some people. As results suggested, teachers indicated students use ICT for their personal use, especially social matters and business. When asked about the role of ICT in language education today, they indicated that creativity is an important part to integrate ICT in EFL class today. Teachers showed the importance of ICT requirements in today’s language education as it facilitates language learning during schools’ closure. Results also demonstrated that a low number of teachers’ report that they are integrating technology in EFL activities simply because this is established in the course guidelines rather than they believe it has intrinsic benefits. Whilst this is a minority view, it does confirm some responses given in e.g. Chang (2020), Jácome et al. (2020), Khlaif et al. (2020), Koskela et al. (2020), Lee et al. (2021), Mokh et al. (2021), Nashruddin et al. (2020), and Sherwani & Kilic (2017).

6.2 Beliefs of English language in-service teachers on the use and support of technology in language teaching due to the gender variable

The overall level of significance is 0.000 in Table 6, and the total value of responses from both male and female in-service teachers on the usage and support of technology in their teaching was 3.878. The high levels of agreement teachers expressed in relation to the first and second domains, as shown above, are indicative of their perception that ICT has a positive impact on people’s lives and the use of ICT in education today. Teachers’ responses on the first domain are *M = 4.29, the significance level is 0.000, and on the second domain are M = 3.68, the significance level is 0.007 in favor of males. According to earlier research, female teachers are less likely than their male counterparts to use computers personally. They also indicated that there were no statistically significant differences in the domains (My Skills for Using ICT in Education; and The Use of ICT and My Learning and Teaching Goals in EFL Class) due to the gender variable. In terms of how much ICT is used to support teaching, male and female in-service teachers did not seem to have a significant difference. These results confirm with previous results provided by Gebhardt et al. (2019), Islahi et al. (2019) and Yuen & Ma (2002).

6.3 Beliefs of English Language teachers towards the use and support of technology in language teaching due to their professional experience

In order to gain an impression of their beliefs on the use and support of technology in language teaching due to the professional experience variable, a survey questionnaire was distributed to English language teachers. We ran ANOVA tests and the scores indicate a high level of significance.

Due to various levels of professional experience, that there are disparities in the ways of English in-service language instructors’ opinions towards the use of ICT in English language teaching . The second test which was needed to identify the significance of the differences is One-Way ANOVA.

Results show that there were statistically significant differences in the domain My Skills for Using ICT in Education due to professional experience variable. To find theof a future study. However, the source of the differences, the researchers used the Scheffe test for two-dimensional comparisons of the differences between averages of the Skills for Using ICT in Language Education due to professional experience.

It is discovered that those who have been teaching less than 10 years had more favourable opinions towards, and beliefs about, the use of ICT in English language teaching. A simplistic reading of this result is that younger language teachers were more used to using ICT and have a greater affinity to it. These results concur with the studies conducted by Crang et al. (2006), Mahdi and Al-Dera (2013), Saglam & Sert (2012) and Sutrisno et al. (2021). However, the idea of digital ‘natives’ or ‘residents’ has long been superseded and abandoned. That teachers believed more strongly in the uses of ICT in language learning because they have used digital tools and applications more during their formative years, or did so more during their pre-service teaching than more professional experience (and thus older) teachers is conjecture, but will be the focus of a future study. However, the results are consistent with the studies conducted by Apriani et al. (2019), Hashemi (2021), Hidalgo-Andrade et al. 2021), Lin et al. (2014), Msila (2015), Nair et al. (2012), Navarro-Espinosa et al. (2021) and Rahimi & Yadollahi (2011).

7 Summary

This study explored the use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in teaching English language from the perspective of English language teachers in Palestine. It also studied whether gender and years of teaching professional experience influence their beliefs about ICT integration into English language teaching. There is no doubt that stepping into the world of technology usage is no longer an individual choice for teachers and students especially with the outbreak of the pandemic. As indicated above, the beliefs of English language teachers towards the use and integration of technology in language teaching was moderate on all domains. The highest domain in ICT is the Use of Information and Communications Technology in Students Lives. This domain is the highest in rank which means that the technological advancements have influenced the people. Teachers believe that ICT can assist students thrive in their future careers, however technical abilities are not given enough weight to help them advance in their chosen professions. Although teachers feel that ICT has altered traditional definitions of social interaction, means of communication and involvement, and the formation of ideas, cultural hurdles to integrating technology into people’s daily lives could be a factor in this. The second domain is The use of ICT in Education Today where a moderate percentage of teachers believe that they feel creativity needs to be integrated into EFL classes and that ICT can help here. Palestinian teachers think ICT requires educators to start teaching in a different way, and that it is essential to integrate ICT into teaching EFL. However, they feel ICT does not yet promote learning in EFL class as much as it should do. The third domain was The Use of ICT and My Learning and Teaching Goals in EFL Class. Teachers feel they would be good designers of materials and EFL activities with ICT; that they developed a lot of skills in order to adopt and adapt new practices in ICT to their learning and teaching needs, but that these skills need to be deliberately taught rather than picked up on an ad-hoc basis. Teachers believe they are high-level users of ICT in EFL class as the classes nowadays are a part of the global education. Finally, the domain My Skills for Using ICT in Education showed that teachers understand and believe that ICT is vital for collaborative learning.

8 Limitations and mitigations

The major potential limitations of this study are listed below. For each, we have demonstrated how we have tried to mitigate the effects:

-

i)

Lack of generalizability: the results of our study may not be representative of the full population of Palestinian English language teachers, but we present these findings as truly representative of the views of those who participated (21%).

-

ii)

Limited statistical power: small sample sizes may not provide enough statistical power to detect meaningful differences or relationships between variables. However, the levels of significance were high for all tables in our study, giving us faith in their accuracy.

-

iii)

Limited technology access: the sample may not fully represent diverse groups of people with varying access to technology, which is particularly true in Palestine, but we believe we reached a good cross-section of language teachers.

-

iv)

Cost and time constraints: conducting a larger-scale study would be time-consuming and expensive, which was not feasible for this unfunded research, but we believe that 780 respondents is a credible figure for our study and its conclusions.

9 Recommendations and implications for theory and practice

Whilst there these limitations to this study exist, along with others such as it being restricted to English language teachers only, and its use of a sample rather than all language teachers in Palestine, as we have said, we believe that the findings are credible and valid in representing the views and perspectives of participants faithfully. We also deem our questionnaire to be effective, drawing as it did on a number of previous published studies (see Fig. 1). We can conclude that instructors believe ICT is essential in the teaching-learning environment with regard to our first particular purpose, which was to explain teachers’ perspectives and beliefs about the use of technology to enhance language teaching and learning. They believe that mastering technology is a crucial ability for success in both the professional and personal lives. However, it is evident that this only happens on a personal level, leaving learners at the mercy of individual educators’ confidence and competence to embed new ICT pedagogies and infrastructure into courses. As a result of this, it would make sense for a proactive e-learning policy for ICT integration in schools to be established by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education of the Palestinian National Authority. This would make it possible for both students and teachers to advance their learning. Schools should carefully think about how they could implement a more comprehensive program to overcome the difficulties teachers encounter. These proactive measures from schools and higher education institutions could potentially help students and teachers. ICT is viewed positively by instructors, therefore initiatives by the government to improve school e-learning will have an impact on their instruction. Teachers should be motivated to increase communication and share their ICT implementation in teaching experiences and education. However, the use of digital resources for education is varied throughout educational levels. Research, and evidence of possible best practice, is equally patchy, so we would call for further research that builds around local contexts. As noted in Traxler et al. (2020 p55), “without robust funding for a secure and fully accessible digital infrastructure, and a plan to achieve and sustain this, the educational, social, economic and other affordances of digital technology will struggle to develop,” lending further urgency to our call for a policy-driven approach that will help educators unlock the benefits that they have identified in this paper.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abduh, M. (2021). Full-Time Online Assessment during Covid-19 Lockdown: EFL Teacher’s Perceptions.Asian EFL Journal Research Article, 28.

Adarkwah, M. A. (2021). “I’m not against online teaching, but what about us?”: ICT in Ghana post Covid-19. Education and Information Technologies, 26(2), 1665–1685.

Affouneh, S., Khlaif, Z. N., Burgos, D., & Salha, S. (2021). Virtualization of Higher Education during COVID-19: a successful case study in Palestine. Sustainability, 13(12), 6583.

Ali, W. (2020). Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: a necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. Higher Education Studies, 10(3), 16–25.

Alismail, H. A., & McGuire, P. (2015). 21st Century Standards and Curriculum: current research and practice. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(6), 150–154. https://doi.org/10.7176/JEP.

Almanthari, A., Maulina, S., & Bruce, S. (2020). Secondary school mathematics teachers’ views on E-learning implementation barriers during the COVID-19 pandemic: the case of Indonesia. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics Science and Technology Education, 16(7), em1860.

Al-Shammari, A. H. (2020). Social Media and English Language Learning during Covid-19: KILAW Students’ Use, Attitude, and Prospective.Linguistics Journal, 14(1).

Aničić, K. P., Divjak, B., & Arbanas, K. (2016). Preparing ICT graduates for Real-World Challenges: results of a Meta-analysis. IEEE Transactions on education, 60(3), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1109/TE.2016.2633959.

Aniq, L. N., Drajati, N. A., & Fauziati, E. (2021). Unravelling Teachers’ beliefs about TPACK in Teaching writing during the Covid-19 pandemic. AL-ISHLAH: Jurnal Pendidikan, 13(1), 317–326.

Apriani, E., Supardan, D., Sartika, E., Suparjo, S., & Hakim, I. N. (2019). Utilizing ICT to develop Student’s Language Ethic at Islamic University. POTENSIA: JurnalKependidikan Islam, 5(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.24014/potensia.v5i1.6279.

Arono, A., Syahriman, S., Nadrah, N., Villia, A. S., & Susanti, E. (2021). Comparative Study of Digital literacy in Language Learning among Indonesian Language Education and English Language Education Students in the New Normal Era. https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.16-10-2020.2305230

Ayat, M., Imran, M., Ullah, A., & Kang, C. W. (2020). Current Trends Analysis and Prioritization of Success factors: a systematic literature review of ICT Projects. International journal of managing projects in business. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-02-2020-0075.

Aydin, S. (2013). Teachers’ perceptions about the use of computers in EFL teaching and learning: the case of Turkey. Computer assisted language learning, 26(3), 214–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2012.654495.

Ayoub, N., & Ahmad, A. (2020). The obstacles to integrate information and Communication Technology (ICT) in Kindergartens’ education from the Headmistresses View Point:ِA survey study in Salfeet Governorate/Palestine. Journal of Education and Human Development, 9(3), 109–121.

Bakkum, L., Schuengel, C., Sterkenburg, P. S., Frielink, N., Embregts, P. J., de Schipper, J. C., & Tharner, A. (2022). People with intellectual disabilities living in Care Facilities Engaging in virtual social contact: a systematic review of the Feasibility and Effects on Well-Being. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 35(1), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12926.

Barlott, T., Aplin, T., Catchpole, E., Kranz, R., Le Goullon, D., Toivanen, A., & Hutchens, S. (2020). Connectedness and ICT: opening the door to possibilities for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 24(4), 503–521. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1744629519831566.

Bashir, A. (1988). Technology in learning and teaching. (Trans.) Amman, Dar Al Shoroq.

Bazimaziki, G. (2020). Challenges in using ICT gadgets to cope with effects of COVID-19 on education: a short survey of online teaching literature in English. Journal of Humanities and Education Development (JHED), 2(4), 299–307.

Beardsley, M., Albó, L., Aragón, P., & Hernández-Leo, D. (2021). Emergency education effects on teacher abilities and motivation to use digital technologies. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1455–1477.

Bond, M. (2020). Schools and emergency remote education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a living rapid systematic review. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(2), 191–247.

Brownlee, J., Schraw, G., & Berthelsen, D. (2011). Personal epistemology and teacher education. London: Routledge.

Cahyadi, A. (2020). Covid-19 outbreak and New Normal Teaching in Higher Education: empirical resolve from islamic universities in Indonesia. DinamikaIlmu, 20(2), 255–266.

Carvalho, J., Casado, I. S., & Delgado, S. C. (2020). Conditioning factors in the integration of technology in the teaching of Portuguese Non-Native Language: a Post-COVID 19 reflection for the current training of Teachers. International Journal of Learning Teaching and Educational Research, 19(9), https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.19.9.11.

Cesco, S., Zara, V., De Toni, A. F., Lugli, P., Evans, A., & Orzes, G. (2021). The Future Challenges of Scientific and Technical Higher Education. Tuning Journal for Higher Education, 8(2), 85–117. https://doi.org/10.18543/tjhe-8(2)-2021pp85-117.

Chamorro, M. G., & Rey, L. (2013). Teachers’ beliefs and the integration of technology in the EFL Class. How Journal, 20(1), 51–72.

Chang, W. J. (2020). Cyberstalking and Law Enforcement. Procedia Computer Science, 176, 1188–1194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2020.09.115.

Cicha, K., Rizun, M., Rutecka, P., & Strzelecki, A. (2021). COVID-19 and higher education: first-year students’ expectations toward distance learning. Sustainability, 13(4), 1889.

Comi, S. L., Argentin, G., Gui, M., Origo, F., & Pagani, L. (2017). Is it the way they use it? Teachers, ICT and student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 56, 24–39.

Crang, M., Crosbie, T., & Graham, S. (2006). Variable geometries of connection: urban digital divides and the uses of information technology. Urban Studies, 43(13), 2551–2570.

Feiman-Nemser, S., McDiarmid, G., Melnick, S., & Parker, M. (1987). Changing beginning teachers’ conceptions: A description of an introductory teacher education coursehttp://ncrtl.msu.edu/http/rreports/html/pdf/rr891.pdf

Ferdig, R. E., Baumgartner, E., Hartshorne, R., Kaplan-Rakowski, R., & Mouza, C. (Eds.). (2020). Teaching, technology, and teacher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: stories from the field. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education.

Fitri, Y., & Putro, N. H. P. S. (2021, March). EFL Teachers’ Perception of the Effectiveness of ICT-ELT Integration During the COVID-19 Pandemic. In International Conference on Educational Sciences and Teacher Profession (ICETeP 2020) (pp. 502–508). Atlantis Press.

Fosnot, C. (1989). Enquiring teachers, enquiring learners: a constructivist approach for teaching. New York: Teachers College Press.

Fraser, P., & Ikoma, S. (2015). Regimes of teacher beliefs from a comparative and international perspective. Promoting and sustaining a quality teacher workforce. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Gandhi, S. M. G., Hethesia, D., & Monica, J. A. (2020). Revitalizing the collegiate students with effective reading skill techniques through ict initiatives during COVID 19. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(19), 4511–4517.

Garrison, D. R. (1993). A cognitive constructivist view of distance education: an analysis of teaching-learning assumptions. Distance education, 14(2), 199–211.

Gebhardt, E., Thomson, S., Ainley, J., & Hillman, K. (2019). Teacher Gender and ICT. In: Gender Differences in Computer and Information Literacy. IEA Research for Education, 8 Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26203-7_5

Ghavifekr, S., & Rosdy, W. A. W. (2015). Teaching and learning with technology: effectiveness of ICT integration in schools. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 1(2), 175–191.

Gómez, J., Tayebi, A., & Delgado, C. (2021). Factors that influence Career Choice in Engineering students in Spain: a gender perspective. IEEE Transactions on Education, 65(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1109/TE.2021.3093655.

Habibi, A., Yusop, F. D., & Razak, R. A. (2020). The role of TPACK in affecting pre-service language teachers’ ICT integration during teaching practices: indonesian context. Education and Information Technologies, 25(3), 1929–1949.

Hashemi, A. (2021). Online teaching experiences in higher education institutions of Afghanistan during the COVID-19 outbreak: Challenges and opportunities. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 8(1), 1947008.

Hidalgo-Andrade, P., Hermosa-Bosano, C., & Paz, C. (2021). Teachers’ mental health and self-reported coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ecuador: a mixed-methods study. Psychology research and behavior management, 14, 933. https://doi.org/10.2147%2FPRBM.S314844.

Hismanoglu, M. (2012). Prospective EFL teachers’ perceptions of ICT integration: a study of distance higher education in Turkey. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 15(1), 185–196.

Hussin, A. A. (2018). Education 4.0 made simple: ideas for teaching. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 6(3), 92–98. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.6n.3p.92.

Islahi, F., & Nasrin, D. (2019). Exploring teacher attitude towards Information Technology with a gender perspective. Contemporary Educational Technology, 10(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.30935/cet.512527.

Jácome, C., Marques, A., Oliveira, A., Rodrigues, L. V., & Sanches, I. (2020). Pulmonary telerehabilitation: an international call for action. Pulmonology, 26(6), 335.https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.pulmoe.2020.05.018.

Khatoony, S., & Nezhadmehr, M. (2020). EFL teachers’ challenges in integration of technology for online classrooms during coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Iran. AJELP: Asian Journal of English Language and Pedagogy, 8(2), 89–104.

Khlaif, Z. N., Salha, S., Affouneh, S., Rashed, H., & El Kimishy, L. A. (2020). The Covid-19 epidemic: teachers’ responses to school closure in developing countries. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 1–15.

Kimav, A. U., & Aydin, B. (2020). A blueprint for in-service teacher training program in technology integration. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning, 3(3), 224–244.

Korkmaz, S., Kazgan, A., Çekiç, S., Tartar, A. S., Balcı, H. N., & Atmaca, M. (2020). The anxiety levels, quality of sleep and life and problem-solving skills in healthcare workers employed in COVID-19 services. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 80, 131–136.

Koskela, T., Pihlainen, K., Piispa-Hakala, S., Vornanen, R., & Hämäläinen, J. (2020). Parents’ views on Family Resiliency in sustainable remote schooling during the COVID-19 outbreak in Finland. Sustainability, 12(21), 8844. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218844.

Kundu, A., Bej, T., & Dey, K. N. (2020). An empirical study on the correlation between teacher efficacy and ICT infrastructure. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 37(4), 213–238. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-04-2020-0050.

Lan, W., & Lam, R. (2020). Exploring an EFL Teacher’s Beliefs and Practices in Teaching Topical Debates in Mainland China. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 8(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.30466/ijltr.2020.120806.

Laumer, S., & Maier, C. (2021). How Soccer Referees Changed their Mind: A Belief-Update Perspective on Digital Learning during the Covid-19 Pandemic. https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2021/adopt_diffusion/adopt_diffusion/13

Lee, Y. C., Malcein, L. A., & Kim, S. C. (2021). Information and Communications Technology (ICT) usage during COVID-19: motivating factors and implications. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(7), 3571. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073571.

Lepp, L., Aaviku, T., Leijen, Ä., Pedaste, M., & Saks, K. (2021). Teaching during COVID-19: the decisions made in teaching. Education Sciences, 11(2), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11020047.

Liljedahl, P. (2008). Teachers’ insights into the relationship between beliefs and practice. In D. Maab, & W. Schloglmann (Eds.), Beliefs and attitudes in mathematics education: new research results. Rotterdam, NL: Sense Publishers.

Lin, C. Y., Huang, C. K., & Chen, C. H. (2014). Barriers to the adoption of ICT in Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language in US universities. ReCALL, 26(1), 100–116. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344013000268.

Lucas, M., Bem-haja, P., Santos, S., Figueiredo, H., Ferreira Dias, M., & Amorim, M. (2022). Digital proficiency: sorting real gaps from myths among higher education students. British Journal of Educational Technology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13220.

Maasepp, B., & Bobis, J. (2014). Prospective primary teachers’ beliefs about Mathematics. Mathematics Teacher Education and Development, 16(2), 89–107.

Mahdi, H. S., & Al-Dera, A. S. A. (2013). The impact of Teachers’ age, gender and Professional experiences. On the Use of Information and Communication Technology in EFL Teaching. English Language Teaching, 6(6), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v6n6p57.

Maican, M. A., & Cocoradă, E. (2021). Online Foreign Language Learning in Higher Education and its correlates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(2), 781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020781.

Many, J., Howard, F., & Hoge, P. (2002). Epistemology and pre service teacher education: how do beliefs about knowledge affect our students’ Professional Experiences? English Education, 34(4), 445–461. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40173077.

Marchlik, P., Wichrowska, K., & Zubala, E. (2021). The Use of ICT by ESL Teachers Working with Young Learners during the early COVID-19 pandemic in Poland.Education and Information Technologies,1–25.

Mirzajani, H., Mahmud, R., Ayub, A. F. M., & Wong, S. L. (2016). Teachers’ acceptance of ICT and its integration in the classroom. Quality Assurance in Education, 24(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-06-2014-0025.

Mokh, A. J. A., Shayeb, S. J., Badah, A., Ismail, I. A., Ahmed, Y., Dawoud, L. K., & Ayoub, H. E. (2021). Levels of Technostress resulting from Online Learning among Language Teachers in Palestine during Covid-19 pandemic. American Journal of Educational Research, 9(5), 243–254. http://pubs.sciepub.com/education/9/5/1.

Moorhouse, B. L., & Beaumont, A. M. (2020). Utilizing Video Conferencing Software to teach Young Language Learners in Hong Kong during the COVID-19 Class Suspensions. TESOL Journal, 11(3), https://doi.org/10.1002%2Ftesj.545.

Msila, V. (2015). Teacher Readiness and Information and Communications Technology (ICT) Use in Classrooms: A South African Case Study. Creative Education, 6(18), 1973. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2015.618202

Mustafa, M., & Abbas, A. (2021). Comparative analysis of Green ICT Practices among palestinian and malaysian in SME Food Enterprises during covid-19 pandemic. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology, 18(4), 254–264. https://archives.palarch.nl/index.php/jae/article/view/5692.

Nabulsi, N., McNally, B., & Khoury, G. (2021). Improving graduateness: addressing the gap between employer needs and graduate employability in Palestine. Education + Training.63 (6), 947–963. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2020-0170

Nair, G. K. S., Rahim, R. A., Setia, R., Adam, A. F. B. M., Husin, N., Sabapathy, E., & Seman, N. A. (2012). ICT and teachers’ attitude in English language teaching. Asian Social Science, 8(11), 8. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v8n11p8.

Nashruddin, N., Alam, F. A., & Tanasy, N. (2020). Perceptions of teacher and students on the Use of e-mail as a medium in distance learning. Berumpun: International Journal of Social Politics and Humanities, 3(2), 182–194.

Navarro-Espinosa, J. A., Vaquero-Abellán, M., Perea-Moreno, A. J., Pedrós-Pérez, G., Aparicio-Martínez, P., & Martínez-Jiménez, M. (2021). The higher education sustainability before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a spanish and ecuadorian case. Sustainability, 13(11), https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116363.

Ntshwarang, P. N., Malinga, T., & Losike-Sedimo, N. (2021). E-Learning tools at the University of Botswana: relevance and use under COVID-19 Crisis. Higher Education for the Future, 8(1), 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2347631120986281.

Nugroho, A., & Mutiaraningrum, I. (2020). EFL Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices about Digital Learning of English. EduLite:. Journal of English Education Literature and Culture, 5(2), 304–321.

Palestine Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (2020). Schools Distribution in Palestine According to District and Territory. Retrieved on 10, July, 2021 from https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/Portals/_Rainbow/Documents/Schools_ar.html

Qaddumi, H., Bartram, B., & Qashmar, A. L. (2021). Evaluating the impact of ICT on teaching and tearning: a study of palestinian students’ and Teachers’ perceptions. Education and Information Technologies, 26(2), 1865–1876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10339-5.

Rababah, L. (2020). ICT Obstacles and Challenges Faced by English Language Learners during the Coronavirus Outbreak in Jordan. International Journal of Linguistics, 12(1), 20–28.

Rahiem, M. D. (2020). Technological barriers and challenges in the use of ICT during the COVID-19 emergency remote learning. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(11B), 6124–6133.

Rahim, M. N., & Chandran, S. S. C. (2021). Investigating EFL Students’ perceptions on E-learning paradigm-shift during Covid-19 pandemic. Elsya: Journal of English Language Studies, 3(1), 56–66.

Rahimi, M., & Yadollahi, S. (2011). Computer anxiety and ICT integration in english classes among iranian EFL Teachers. Procedia Computer Science, 3, 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2010.12.034.

Rakıcıoğlu-Söylemez, A., & Akayoğlu, S. (2019). Prospective EFL teachers’ perceptions of using CALL in the Classroom. Handbook of Research on Educator Preparation and Professional Learning (pp. 189–204). IGI Global.

Reinders, H., Lai, C., & Sundqvist, P. (Eds.). (2022). The Routledge Handbook of Language Learning and Teaching Beyond the Classroom (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003048169

Rizkiani, S. (2021). Professional Competency of Pre-Service English Teachers and ICT during Covid-19 pandemic. Acuity: Journal of English Language Pedagogy Literature and Culture, 6(2), 138–147.

Ryn, A. S., & Sandaran, S. C. (2020). Teachers’ Practices and perceptions of the Use of ICT in ELT Classrooms in the Pre-Covid 19 pandemic era and suggestions for the’New Normal’. LSP International Journal, 7(1), https://doi.org/10.11113/lspi.v7n1.100.

Saglam, A. L. G., & Sert, S. (2012). Perceptions of in-service teachers regarding technology integrated English language teaching. Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, 3(3), 1–14. Retrieved July 29, 2022https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/tojqi/issue/21396/229371?publisher=tojqi

Samara, M. (2021). Towards e-learning in TVET: Setting and developing E-Competence Framework for TVET teachers in Palestine. In: TVET@Asia, 16, 1–15. http://tvet-online.asia/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Samara_issue_16_TVET.pdf(retrieved 10.02.2021).

Sherwani, S. H. T., & Kilic, M. (2017). Teachers’ perspectives of the Use of CLT in ELT Classrooms: a case of Soran District of Northern Iraq. Arab World English Journal, 8(3), https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol8no3.13.

Smith, M., & Traxler, J. (2022). Digital Learning in Higher Education: Covid-19 and Beyond. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishers. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800379404.

Smith, M. (2016). An investigation into the Pedagogical Trajectories of PGCE Trainees using espoused ‘beliefs’. Journal of Education & Social Policy, 3(5), 16–29. http://jespnet.com/journals/Vol_3_No_5_November_2016/3.pdf.

Smith, M. (2017). An investigation into the epistemological trajectories of PGCE student teachers as predicated by their espoused pedagogical beliefs. University of Birmingham. Ed.D.https://etheses.bham.ac.uk//id/eprint/7917/.

Subaih, R. H. A., Sabbah, S. S., & Al-Duais, R. N. E. (2021). Obstacles Facing Teachers in Palestine While Implementing E-learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Asia

Subekti, A. S. (2021). Covid-19-triggered online learning implementation: pre-service english teachers’ beliefs. Metathesis: Journal of English Language Literature and Teaching, 4(3), 232–248.

Supriadi, Y., Nisa, A. A., & Wulandari, S. (2020). English Teachers’ Beliefs on Technology Enhanced Language Learning: A Rush Paradigmatic Shift during Covid-19 Pandemic.Pancaran Pendidikan, 9(2).

Sutrisno, S., Andre, H. L., & Susilawati, S. (2021, February). The Analysis of the Facilities and ICT Applications Usage by the University’s Students. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1793, No. 1, p. 012050). IOP Publishing.

Tamah, S. M., Triwidayati, K. R., & Utami, T. S. D. (2020). Secondary school language teachers’ online learning engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 19, 803–832.

Tandon, U. (2020). Factors influencing adoption of online teaching by school teachers: A study during COVID-19 pandemic.Journal of Public Affairs,e2503.

Traxler, J., Smith, M., Scott, H., & Hayes, S. (2020). Learning through the crisis: Helping decision-makers around the world use digital technology to combat the educational challenges produced by the current COVID-19 pandemic. Report. EdTech Hub. https://edtechhub.org. https://docs.edtechhub.org/lib/CD9IAPFX

Vacc, N., & Bright, G. (1999). Elementary preservice teachers changing beliefs and instructional use of children’s mathematical thinking. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 30(1), 89–211.

Van der Spoel, I., Noroozi, O., Schuurink, E., & van Ginkel, S. (2020). Teachers’ online teaching expectations and professional experiences during the Covid19-pandemic in the Netherlands. European journal of teacher education, 43(4), 623–638.

Wen, K. Y. K., & Kim Hua, T. (2020). ESL Teachers’ intention in adopting online Educational Technologies during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Education and E-Learning Research, 7(4), 387–394.

Wilson, S., & Cooney, T. (2002). Mathematics teacher change and development: the role of beliefs. In G. Leder, E. Pehkonen, & G. Törner (Eds.), Beliefs: a hidden variable in mathematics education. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Yuen, A. H. K., & Ma, W. W. K. (2002). Gender Differences in Teacher Computer Acceptance. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 10(3), 365–382. Norfolk, VA: Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education. Retrieved July 23, 2022 fromhttps://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/15142/.

Zhang, C. (2020). From face-to-face to screen-to-screen: CFL teachers’ beliefs about digital teaching competence during the pandemic. International Journal of Chinese Language Teaching, 1(1), 35–52.

Funding

This work is not funded by anyone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Husam Qaddumi (senior author and corresponding)1Oversight and leadership responsibility for the research activity, conducting a research and investigation process, managing, formulation, creation, planning, materials, preparation, proofreading, revision and writing the original draft.

Matt Smith2Critical review, development, proofreading and editing, commentary or revision.

Khaled Masd3Data collection and one-page writing.

Aida Bakeer3Ideas, revision, one-page writing.

Waheeb Abu -ulbeh4Development of research instrument & Software

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Consent to participate

Manuscript is approved by all participants.

Consent for publication

Manuscript is approved by all authors for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Qaddumi, H., Smith, M., Masd, K. et al. Investigating Palestinian in-service teachers’ beliefs about the integration of information and communication technology (ICT) into teaching English. Educ Inf Technol 28, 12785–12805 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11689-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11689-6