Abstract

The Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) has developed a set of templates for structured reporting of radiology results. To measure how much of the content of conventional narrative (“free-text”) reports is covered by the concepts included in the RSNA reporting templates, we selected five reporting templates that represented a variety of imaging modalities and organ systems. From a sample of 8,275 consecutive, de-identified radiology reports from an academic medical center, we identified one corresponding imaging procedure code for each reporting template. The reports were annotated with RadLex and SNOMED CT terms using the BioPortal Annotator web service. The reporting templates we examined accounted for 17 to 49 % of the concepts that actually appeared in a sample of corresponding radiology reports. The findings suggest that the concepts that appear in the reporting templates occur frequently within free-text clinical reports; thus, the templates provide useful coverage of the “domain of discourse” in radiology reports. The techniques used in this study may be helpful to guide the development of reporting templates by identifying concepts that occur frequently in radiology reports, to evaluate the coverage of existing templates, and to establish global benchmarks for reporting templates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite remarkable advances in medical imaging technologies, the form and content of radiology reports has changed relatively little since the inception of radiology [1]. Unstructured (“free text”) radiology reports remain the most common approach for radiology reporting. Structured radiology reports present information in a consistent format, employ standardized terminology, and allow reported information to be extracted efficiently for indexing and reuse [1]. Although some technological challenges have yet to be overcome [2], referring physicians have a strong preference for structured radiology reports [3–6]. In specialty areas such as cardiovascular imaging, policy statements have signaled a move to structured reporting [7].

To promote structured radiology reporting, the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) has developed a large, freely accessible online library of radiology reporting templates (http://www.radreport.org) [8]. Radiologists and other users can browse, retrieve, and download templates in text format or encoded in the Extensible Markup Language. An application programming interface allows one to search template metadata and download reporting templates as a web service. Because information in a structured reporting template adheres to a consistent format and vocabulary, it is easier to integrate that information with generalized knowledge-based resources and incorporate the structured reporting process with clinical guidelines and decision support.

As of January 2013, the RSNA report template library contained 200 reporting templates in English and 45 templates translated into several other languages. The templates are intended to serve as examples of “best practice” to guide radiologists in formulating reports [8]. Each reporting template has associated metadata, including information about the template’s title, creator, subject, description, and date. The elements of the reporting templates have been mapped to corresponding terms in standardized biomedical ontologies such as the RadLex® radiology lexicon and the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT®) vocabulary [9].

RadLex® is a unified language of radiology terms for standardized indexing and retrieval of radiology information resources [10, 11]. RadLex® has more than 34,000 terms, including diseases, radiologically pertinent anatomy, and imaging observations. It is organized as an ontology and includes subsumption (“is-a”) relationships to demarcate superclass–subclass relations among its terms. SNOMED CT®, an ontology of more than 310,000 terms, is considered to be the most comprehensive, multilingual clinical healthcare terminology in the world [12, 13]. SNOMED CT® is widely used in clinical information systems.

The National Center for Biomedical Ontology (NCBO) BioPortal web site (http://bioportal.bioontology.org) provides access to an open repository of biomedical ontologies via web services, and allows users to browse, search, and visualize ontologies. It contains ontologies that cover a broad range of biomedical topics, including anatomy, phenotypes, experimental conditions, imaging, chemistry, and health. BioPortal allows users to utilize ontologies for annotation of biomedical data on their sites in order to facilitate interoperability, search, and translational discoveries. Both RadLex® and SNOMED CT® can be accessed through NCBO BioPortal.

Standardized terminologies are used to reduce ambiguity and improve the clarity of radiology reports and image annotations, and provide a uniform means of indexing radiological materials in a variety of settings [9]. In this study, we sought to evaluate how well the RSNA reporting templates covered the “domain of discourse” of actual radiology reports. We measured how frequently terms from the reporting templates appeared in conventionally dictated, narrative (“free-text”) radiology reports. Our hypothesis was that the reporting templates included the more frequently used terms in clinical radiology reports.

Material and Methods

Five reporting templates for frequently performed procedures (computed tomography (CT) brain, chest X-ray, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging spine, nuclear medicine (NM) bone scan, and ultrasonography (US) abdomen) were chosen from the RSNA reporting template library. The templates represented a variety of imaging modalities, such CT, MR imaging, radiography, NM, and US, and a variety of body areas and organ systems (thorax, brain, abdomen, and skeletal system). To identify the concepts that appeared in the templates, we extracted the reporting elements from each template. These reporting elements—terms such as “left kidney,” “hydronephrosis,” and “mild”—described potential report content that could appear in encoded form within a structured report based on the specified template.

A series of 8,275 consecutive, de-identified radiology reports from an academic medical center served as the test set for this investigation. The study protocol received Institutional Review Board approval and the study was performed in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. All of the reports were created by voice dictation, and were transcribed either manually or using a speech recognition system. The report text represented final, approved report content, and consisted of the procedure name, narrative (“findings”) section, and report impression. The reports and the reporting templates were created independently. The reports were created about 2 years before the templates were developed; the reporting templates were developed by national committees without access to a specific set of radiology reports.

For each reporting template, we identified a single corresponding radiology procedure name from the institution’s charge master. For example, the “Chest Xray” template was matched with the “DX CHEST XRAY PA-LAT” procedure code. Other chest radiographic procedures, such as single-view chest examinations, were not included in this analysis. The reporting templates and corresponding radiological procedure codes are shown in Table 1.

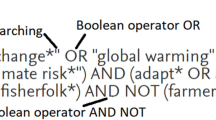

We applied the NCBO BioPortal Annotator [14] (http://bioportal.bioontology.org/annotator) to identify matching concepts from the RadLex and SNOMED CT vocabularies with terms in our sample of reporting templates and free-text reports. The Annotator processes text submitted by users through a RESTful web interface, uses string-matching to recognize terms from specified biomedical ontologies within the given text, and returns the annotations to the user [15].

First, we applied BioPortal Annotator to identify RadLex and SNOMED CT concepts from each reporting template. Then, for each clinical radiology report, BioPortal Annotator was used to annotate the clinical reports with matching RadLex and SNOMED CT concepts. Report annotation was automated completely through the NCBO Annotator’s web service, and results were stored in a database. In our analysis, the number of “Unique Concepts” represents the number of distinct concepts from these two ontologies that appear in at least one of the clinical reports for a specific radiology procedure. We defined “Concept Occurrences” as the sum of the number of reports in which each of the unique concepts occurs. For all of the reports of a specific procedure, we tallied the number of unique concepts identified by the annotation process and the total number of clinical reports in which each concept occurred. We compared the concepts that appeared in the report templates (“template-based concepts”) with the concepts that appeared in free-text reports.

Results

The five reporting templates are shown in Table 2 with the number of elements and concepts for each template. The number of reporting elements indicates how many predefined terms such as section headings (e.g., “Findings”), anatomic sites (e.g., “Left kidney”), observation descriptors (“Hydronephrosis”), and predefined values (e.g., “Severe”) appear in the reporting template. Each element may have mapped to zero, one, or more than one term in a vocabulary; the total number of annotations is shown in the rightmost column. For example, the 25 elements of the chest radiograph reporting template were mapped to 41 concepts (“Appendices” section).

The annotation results of the full-text reports are shown in Table 3. The 860 chest radiograph exam (“DX CHEST PA-LAT”) reports, for example, contained 2,360 unique concepts, of which 33 (1.4 %) matched the 41 concepts generated from the corresponding reporting template (“Chest Xray”). As expected, this result indicates the reporting template contains far fewer terms than those found in actual radiology reports. Of the 53,624 concept occurrences for this procedure’s reports, however, 9,931 (17.2 %) were related to concepts that appeared in the reporting template.

As shown in Table 3, the template-based concepts appeared significantly more frequently. The 33 concepts in the “Chest Xray” template appeared 14.7 times more frequently in actual reports than concepts that did not appear in the reporting template. For all five of the procedures studied here, the template-based concepts appeared in actual reports at least 2.5 times more frequently than non-template-based concepts. The chi-squared test for each report type showed a significant difference at a threshold of p < 0.00001.

Discussion

The RSNA reporting templates have been created to represent “best practice” in radiology reporting [8], rather than as a normative standard. In general, the templates were crafted by national committees of subspecialty experts or as “time-tested” examples of reporting templates used at individual institutions. That the reporting templates adequately capture the salient aspects of corresponding radiology reports is an untested hypothesis. The experiment described here sought to evaluate the extent to which the RSNA reporting templates covered the content of corresponding free-text reports.

The RSNA reporting templates that we examined accounted for no fewer than 17 % and up to 49 % of the concept occurrences in a sample of corresponding radiology reports. Although the reporting templates contained a small number of unique concepts, their concepts appeared with high frequency in radiology reports. For all reports in this study, template-based concepts appeared in actual reports at least 2.5 times more frequently than non-template-based concepts.

This study had several limitations. We examined a small number of reporting templates, and explored reports of only one procedure type for each template. The reports were obtained over a relatively brief period (1 week) from a single institution, and hence may reflect individual biases. The NCBO Annotator often identified multiple concepts for a specific term. For example, the phrase “right kidney” was mapped to annotations for “right,” “kidney,”, “right kidney,” “entire kidney,” “kidney structure,” and “right kidney structure.” Such redundancy may artificially increase the percentage of matching terms.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our results provide useful estimates of how well the reporting templates capture the concepts that appear frequently in radiology reports. A more “complete” template may be desirable, but it is likely to be more complex and possibly more difficult to use. Even a relatively simple template, such as “Chest Xray,” addressed almost one-fifth of the concepts that appeared in two-view chest radiograph reports. The techniques used here may be helpful to determine the appropriate complexity of radiology reporting templates, and to identify those concepts that appear most frequently and should be considered for inclusion in the templates. Such techniques may be incorporated into automated approaches to construct reporting templates that optimally model the content of clinical radiology reports.

Conclusion

The reporting templates analyzed in this study yielded 17 to 49 % of the concept occurrences in actual radiology reports, and contained concepts that appeared significantly more frequently than others. This finding suggests that the RSNA reporting templates provide useful coverage of the “domain of discussion” in radiology reports. The techniques used in this study can guide the development of reporting templates by identifying concepts that occur frequently in radiology reports. These techniques also can help evaluate the coverage of existing templates and establish global benchmarks for reporting templates.

References

Weiss DL, Langlotz CP: Structured reporting: patient care enhancement or productivity nightmare? Radiology 249:739–747, 2008

Langlotz CP: Structured radiology reporting: are we there yet? Radiology 253:23–25, 2009

Bosmans JM, Weyler JJ, De Schepper AM, Parizel PM: The radiology report as seen by radiologists and referring clinicians: results of the COVER and ROVER surveys. Radiology 259:184–195, 2011

Schwartz LH, Panicek DM, Berk AR, Li Y, Hricak H: Improving communication of diagnostic radiology findings through structured reporting. Radiology 260:174–181, 2011

Sistrom CL, Honeyman-Buck J: Free text versus structured format: information transfer efficiency of radiology reports. AJR Am J Roentgenol 185:804–812, 2005

Grieve FM, Plumb AA, Khan SH: Radiology reporting: a general practitioner’s perspective. Br J Radiol 83(985):17–22, 2010

Douglas PS, et al: ACCF/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HRS/NASCI/RSNA/SAIP/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR 2008 Health policy statement on structured reporting in cardiovascular imaging. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 53:76–90, 2009

Kahn, CE Jr, et al: Toward best practices in radiology reporting. Radiology 252:852–856, 2009

Hong Y, Zhang J, Heilbrun ME, Kahn, CE Jr: Analysis of RadLex coverage and term co-occurrence in radiology reporting templates. J Digit Imaging 25:56–62, 2012

Langlotz CP: RadLex: a new method for indexing online educational materials. RadioGraphics 26:1595–1597, 2006

Rubin DL: Creating and curating a terminology for radiology: ontology modeling and analysis. J Digit Imaging 21:355–362, 2008

Elkin PL, et al: Evaluation of the content coverage of SNOMED CT: ability of SNOMED clinical terms to represent clinical problem lists. Mayo Clin Proc 81:741–748, 2006

SNOMED Clinical Terms. 2013. http://www.ihtsdo.org/snomed-ct/. Accessed 16 Jan 2013.

Jonquet C, Shah NH, Musen MA: The open biomedical annotator. Summit on Translational Bioinformatics 2009:56–60, 2009

Whetzel PL, et al: BioPortal: enhanced functionality via new Web services from the National Center for Biomedical Ontology to access and use ontologies in software applications. Nucleic Acids Res 39:W541–545, 2011

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB). We thank the RSNA Radiology Informatics Committee for leading and supporting the radiology reporting initiative, and we acknowledge the many RSNA volunteers who helped develop the reporting templates.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Sample narrative (free-text) chest radiography report

Narrative

Chest. Comparison: 03/06/07. AP upright and left lateral upright views of the chest reveal a transverse cardiac diameter that is within normal limits. There is mild tortuosity and ectasia of the thoracic aorta which is unchanged. Mediastinal width and pulmonary vasculature is normal. The lung fields are free of infiltrate, consolidation, or effusion. There is evidence of hyperinflation with increased AP chest dimension. One questions if patient has an element of obstructive pulmonary disease. Again noted is a sending device overlying the left midlung field. An electrode lead extends cephalad into the cervical area on the left. This is essentially unchanged from the previous films.

Impression

(1) Aortic tortuosity and ectasia with no acute cardiopulmonary disease. (2) Lung field changes suggestive of obstructive pulmonary disease.

Appendix D

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, Y., Kahn, C.E. Content Analysis of Reporting Templates and Free-Text Radiology Reports. J Digit Imaging 26, 843–849 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-013-9597-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-013-9597-4