Abstract

In this study, a D–A cycloalkanone (K1) has been investigated by steady state absorption and fluorescence in neat solvents and in three binary mixtures of nonpolar aprotic/polar protic, polar aprotic/polar protic, and polar protic/polar protic solvents. The experimental findings were complemented by density functional theory (DFT), time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT), and NBO quantum-mechanical calculations. Experimentally, effective changes in absorption and fluorescence were observed by solute–solvent interaction. The binary K1-solvent1-solv2 configuration, modeled at the B3LYP-DFT level, confirms involvement of inter-molecular H-bonding with the carbonyl C=O in the fluorescence deactivation process (quenching). This is supported by considerable electron delocalization from C=O to the solvent’s hydroxyl (nO → σ*H-O). This type of hyperconjugation was found to be the main driver for solute–solvent stabilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

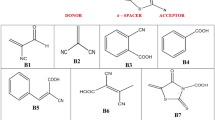

Molecular π-systems with electron donating (D) and electron accepting (A) substituents generally are known as push–pull systems and characterized by intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) [1]. Such conjugated π-systems possess unique properties in both ground and excited states, due to D–A interaction that generates a new low-energy occupied molecular orbital (MO) with charge transfer character.

Compounds bearing a carbonyl (C=O) motif, such as in cycloalkanones, as an acceptor, have been a focus of intensive investigations, due to their biological activity, mainly, antiulcer, anticancer, antimitotic, antioxidant, anti-HIV, and antimalarial [2,3,4,5]. Further, the importance of such systems with the carbonyl substituents is known in many applications, such as optoelectronics [6,7,8,9] and as vibrational probe [10]. Moreover, the carbonyl C=O chromophore is recognized as an important spectroscopic probe in studying intermolecular interactions by means of theoretical methods [11], transient optical [12], solid state 17O NMR [13], UV [14], and IR spectroscopic techniques [10]. In medicinal chemistry, where the C=O is common in many biological structures, it is understood that the oxygen acting as a hydrogen bond acceptor can interact with a binding site. This interaction is possible by two means: i) through dipole–dipole interaction, due to C=O polarization, or ii) via hydrogen bonding (H-bonding) that involves the two lone-pair electrons of the oxygen sp2 hybridized orbital [15]. Moreover, recent studies based on fluorescence spectroscopy showed that cycloalkanones bind to BSA protein and DNA and the outcome of this interaction depends on their concentration [16, 17].

Our interest in these important biologically active cycloalkanones came due to the fact that the complete mechanism for their interaction with DNA and protein is still not completely understood [16, 17]. Thus, in this work, we continue our investigation on one of the cycloalkanones we previously synthesized [18]. This push–pull compound with the carbonyl motif (denoted herein as K1), is built on a strong donor N,N-dimethyl-aniline unit (D) connected to the acceptor (A) cyclic benzoyl group, via a cyclic five-membered ring.

In this study, the effects of the environment, through nonspecific interactions and H-bonding, were considered in neat solvents and binary mixtures of some systems with different polarities and proticities. Binary mixtures are usually used to customize solvent properties in various chemical reactions. Thus, upon mixing, new solvent–solute and solvent–solvent interactions, in many cases, lead to solvent properties different than neat solvents. Furthermore, in a binary mixture, many dynamic and static properties, such as viscosity, solubility, and polarizability among others, change with the variation in the composition of any of the constituents [19].

Experimental details

Synthesis of the compound

(3E(−2-{[4-(N,N-dimethyl-amino)-phenyl]-methylene}-2,3-dihydro-1H-Inden-1-one (K1) (Chart 1). The complete procedure for the synthesis and characterization of the title compound are given in our earlier work [18]. All solvents used in this study were of spectroscopic grades and purchased from Fluka Chemical Co. and used as received.

Spectroscopic techniques

The steady state electronic absorption (using 1 cm matched quartz cells) and fluorescence spectra were recorded at room temperature. Absorption spectra was recorded with Perkin Elmer diode array UV/Vis, while emission spectra were taken with Shimatzu RF-500 spectrometer. Emission spectra were obtained using a small angle (90°) front surface excitation geometry. The slit width was 5 nm for both excitation and emission. The concentration of the compound in all neat and mixed solvents was 1.0 × 10−5 and 1.0 × 10−6 M for absorption and emission measurements, respectively. Fresh solutions were used for all measurements, and emission spectra were not corrected for the spectral response of the instruments. The samples of compound K1 in the binary mixtures were prepared at different solvents ratios (fixed solute concentration).

Computational methods

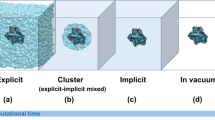

Density functional theory (DFT) has been used for geometry optimizations of the isolated molecules and the hydrogen-bonded solute–solvent complexes. For this purpose, the three-parameter B3LYP density functional including the Becke’s gradient exchange corrections [20] and the Lee–Yang–Parr correlations functions [21] were used. The 6–31G(d,p) and 6–31+G(d,p) [22] were chosen as the basis sets throughout. Here, B3LYP is applied owing to its typically excellent performance in the prediction of geometries and vibrational frequencies for simple organic molecules. Also, the choice of 6–31G+(d,p) is justified by many studies on similar systems, which have shown that this atomic basis set is sufficient for geometries of both ground and excited states [23, 24, 25]. No restrictions were imposed on the geometry optimization. All calculated minima were verified by frequency calculations; no imaginary frequencies were found. Implicit solvent effects were considered using a modified version of the conductor-like polarizable continuum model (C-PCM [26]. Single point energies for the un-relaxed compound K1 or solvent(s) were carried out at the same level of functional and basis set throughout. Default parameters were used for the PCM cavity, and acetonitrile (ACN) and methanol (MeOH) were used as media. Solvation through specific solvent effects were conducted using one or two solvent molecules H-bonded to the C=O of the carboxyl group in the same plane.

The electronic excitation energies as well as the oscillation strengths of the low-lying singlets and triplets electronically excited states were calculated using time-dependent analytical gradients (TD-DFT) [27], with the B3LYP functional (TD-B3LYP) and the 6–31+G(d,p) basis set.

The donor (i) and acceptor (j) electronic interactions were acquired from the natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis, using the second order perturbation energies \( {E}_{i-j}^{(2)} \) of orbital interactions from the filled (lone pair) Lewis type NBO to another neighboring electron deficient orbital (non-Lewis type) σ* antibonding. These NBO charge analysis were performed at the B3LYP/6–31+G(d,p) level of theory [28], on the optimized structures in the gas phase and solution (C-PCM) alike. The stabilization energy, (\( {E}_{i-j}^{(2)} \)), for each NBO(i) and acceptor (j) is generally estimated by the second-order perturbation theory [29, 30, 31] according to:

where qi is the donor orbital occupancy, i and j are diagonal elements (orbital energies), and F(i,j)2 is the off-diagonal NBO Fock-matrix element. The NBO-6 program [32], implemented in the Gaussian 16 package [33], was used for this purpose. All computations, were performed by imposing no symmetry restrictions (Ci point group). All calculations were performed with the latest version of Gaussian 16 program [33], and molecular orbitals visualization were carried out by Gauss View V6.0 [34].

Results and discussion

Steady state absorption and emission

Comparison of absorption and fluorescence in nonpolar cyclohexane (CHX)

The complete ground state absorption and excited state emission results were given in our earlier work [18]. Here, we only give general features of the electronic absorption and emission. The first transition (long wavelength, LW) in this compound was observed at 402 nm in cyclohexane (CHX) and at 432 nm in methanol. In cyclohexane, a shoulder also appears at ~440 nm, and a weak absorption with vibrational feature appears at ~ 300–340 nm. Fluorescence maxima (\( {\overset{\sim }{\nu}}_f^{max}\Big) \)on the other hand, are slightly red-shifted in CHX and found at 420 nm.

This molecule shows a mirror image of absorption and emission, indicating no structural change (planar structure) in the excited state. With regard to the Stokes shift (cf. Fig. 1a and Fig. S1a), compound K1 exhibits a moderate shift of 1066 cm−1 (~ 0.13 eV) in CHX. Our TD-DFT calculations (as will be outlined in the coming section 3.2), show that the origin of the LW band is S0 → S1 1(π,π*), whereas the weak band in the middle region of 300–340 nm is due to S0 → S3 transition and possess a 1(n,π*) signature. The S0 → S2 transition is not seen since it is dark (cf. Tables 1 and 2).

Absorption in nonpolar/polar protic (CHX/MeOH) binary mixture

The effect of H-bonding between the solvent and the carbonyl motif (C=O) of these compounds was studied in a nonpolar/polar protic system, mainly cyclohexane-methanol by titration of K1 in cyclohexane (CHX) solution with increasing the fraction of methanol in the mixture while keeping the solute at constant concentration. As first observation, Fig. 1a shows the absorption of K1 in CHX with increasing MeOH ratio, while the normalized spectra of the same are given in Fig. 1b. Notably, the addition of a small amount of methanol causes a drop in intensity with peak red-shifted. We observe a slight loss of the vibrational feature seen in pure cyclohexane due to S0 → S1 transition (assigned based on TD-DFT calculations, for more information see ref. [18]) with addition of a small quantity of MeOH. As the percentage of MeOH increases, the spectra become structureless and broadened. This occurs owing to site specific interaction of the acidic proton of MeOH with the basic carbonyl C=O. The decrease in intensity is explained by our TD-DFT calculation (full details will be given shortly), where TD-DFT calculation show that the lowest absorption band (S0 → S1 transition) in neat cyclohexane has an oscillator strength of ca. f = 0.855, whereas in MeOH solution (C-PCM solvation model) it is ca. f = 0.836, and further decreases to 0.632 in the K1-MeOH complex, where one methanol molecule is H-bonded to the carbonyl C=O motif. Furthermore, the red-shift of the low-energy band is evident in Fig. 2, where S1 state energy drops with the increase in solvent bulk polarity due to better stabilization of the K1-solvent complex by association of the solute with methanol molecules by H-bonding.

Absorption in polar aprotic/polar protic (ACN-MeOH) and protic/protic (MeOH-H2O) binary mixtures

To complement our understanding of the role of H-bonding on the spectral features of these molecules in the ground state, we carried out absorption titration of compound K1 in two more binary solvent systems. The first solvent system was composed of a polar aprotic and polar protic solvents (acetonitrile/methanol) mixture, and the other system consists of both polar protic solvents (methanol/water). Figures 3 and 4, show the normalized steady state absorption spectra of these two binary systems, while the titrated spectra are given in Fig. S1a and Fig. S1b (supporting information). We notice that, in both mixtures, the band assigned to S0 → S3 transition has almost vanished. However, in the ACN-MeOH mixture, the intensity of the LW band maxima remains relatively unchanged with slight red-shift as the fraction of methanol in the mixture is increased. Further, this band shows a clear broadening with parallel band maxima shift toward lower energy, apparently due to stronger interactions with methanol, which leads to stabilization of the ground state complex. However, the short wavelength at ~300–340 nm (SW) band shows a noticeable decrease in intensity with no change in band position (cf. Fig. 3).

The situation in the K1-MeOH-H2O system is quite different, as shown in Fig. 4. Initially, the LW band drops slowly with progressive shift toward lower energy, following increasing water content till 50% mixture reached. Further increase in the proportion of water results in loosing intensity with no change in position of peak maxima. However, the LW band becomes broader as the fraction of water increased. Moreover, the band intensity drop is noticeable in the SW band as well, though the decrease is steadier than seen in the LW band case.

Structural and electronic features at the ground state

The optimization energies of the title compound K1 in the gas phase, CHX, ACN, and MeOH as calculated by the CPCM-DFT method, are collected in Table 1 and 2. The effect of stabilization of solvation by solvent polarity is obvious, and stability increases in the order: gas phase < CHX < MeOH = ACN. Further, we noticed a slight increase in the dipole moment from the nonpolar CHX to the polar MeOH or ACN.

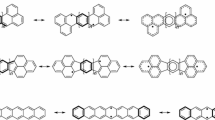

With regard to the orbitals involved in the vertical electronic transitions in this compound, the calculated TD-DFT calculations in the gas phase show that the transition HOMO-1 → LUMO+1 constitutes the major contribution to the S2 state. The HOMO-1 is localized on the carbonyl oxygen (in-plane) and the LUMO+1, is delocalized on the two phenyl rings with neither electron density on the carbonyl nor dimethyl-amine motifs. In the gas phase, S2 state has a n→* character and is not emissive (f = 0.000), whereas S11(π,π*) is an emissive bright state (f = 0.7182) that originates from HOMO→LUMO transition and possesses considerable intramolecular charge transfer character (ICT) from the donor dimethyl aniline to the rest of the molecule (see our earlier work inreference 18).

We plotted the energies of the MO orbitals involved in the electronic transitions in these solvents, and we noticed that LUMO+1 is not sensitive to the solvents type (no change) as the electron density surfaces calculations show that no electron density is found on the carbonyl motif, thus excluding any effects of solvent’s acidity on the spectral changes, due to specific solvent–solute interaction at this site. HOMO MOs are also seen to be insensitive to solvent polarity. However, HOMO-1 and LUMO MOs are stabilized in the order: gas phase < CHX < ACN < MeOH. The higher stability in the protic solvent MeOH reflects the site-specific interaction between the electron rich carbonyl oxygen and the solvent.

The calculated excitation energies for K1, in bulk solvation using the C-PCM model, show that the position of the transition S0 → S1 \( {\overset{\sim }{\nu}}_{abs}^{max}, \) is bathochromically shifted compared to gas phase, whereas that of S0 → S2 is hypsochromically shifted (cf. Fig. 2). The shift of S1 state to lower-energy with the solvent change from the gas phase to MeOH is in accord with the experimentally measured maxima in CHX-MeOH binary mixture, where the band maxima is shifted to lower energy with substantial drop in intensity (cf. Figures 1a and b). The explanation for this, is that S0 → S1 is a 1(π,π*) in nature, with charge transfer from dimethylaniline to the C=O moiety, which will facilitate solute–solvent interaction through H-bonding, causing stabilization to this state.

In Fig. 2, we included the result of our calculations modeling for the complexation of the carbonyl C=O with a single methanol molecule (K1-MeOH) calculated in the gas phase, to gain a better conclusion of the specific solute–solvent interaction. We notice a substantial increase in the S2-S1 and decrease in S3-S1 energy gaps for this structure, compared to the C-PCM solvation method. We believe that this occurs owing to strong H-bonding between K1 and the MeOH molecule, which has a profound effect on the position of both S1 1(π,π*) and S21(n,π*) states.

Inspection of Fig. 2 reveals that the effect of ACN is comparable to MeOH due to their close polarity (εACN = 37.5 and εMeOH = 32.7). We notice that the S2/S1 energy gap (∆E(S2-S1)) is in the order: gas phase (0.0677 eV) < CHX (0.353 eV) < ACN (0.599 eV) < MeOH (0.618 eV), while the same order is found for the S3/S1 gap (1.0534 eV, 1.2125 eV, 1.2557 eV, and 1.2911 eV, respectively). This increasing trend is in qualitative agreement with the experimentally measured values in these solvents, which show that the S3-S1 energy separations are 5959.9 cm−1 (0.74 eV), 6788.6 cm−1 (0.84 eV), and 7621.3 cm−1 (0.94 eV) in CHX, ACN, and MeOH, respectively.

The increase in the S2-S1 energy separation (Table 3), as our calculations show, is a result of destabilization of the S2 state, along with stabilization of the S1 state. Since the S2 state is mainly a HOMO-1 → LUMO transition, which possesses a n→π* character, interaction of the carbonyl-oxygen through H-bonding (as in MeOH) stabilizes HOMO-1 as well as LUMO and LUMO+1 (cf. Fig. S2), while HOMO is not changed. Thus, the separation between HOMO-1/LUMO orbitals is reflected in the ∆ES2/S1 gap (Fig. 2). This blue-shift in the n, π* transition has been a subject of many studies from both theoretical and experimental points of view. It is generally accepted now that change in C=O⋯solvent H-bond strength upon excitation causes the solvatochromic blue-shift in C=O n,π* transition [35, 36]. On the basis of direct field (DRF) calculations, it has been postulated that this blue-shift is attributed to ground state electrostatics of the carbonyl H-bond [37]. Such argument, recently, has found support in the IR study on a range of different compounds with C=O functionalities [38], where the n,π* shifts showed linear sensitivity to calculated electrostatic fields on carbonyls.

Using the CPCM model of solvation, we noticed along with the increase in the S2–S1 gap (cf., Table S2 in the supporting information) a slight decrease in the intensity of S0 → S1 absorption from cyclohexane (f = 0.855) to methanol (0.836). On the other hand, the ∆ES3-S1 increases in the order gas phase (1.0534) < CHX (1.2125) < ACN (1.2557) < 1.2911 (MeOH) (cf. Table 3). However, no changes were noticed in the (ca., ~ f = 0.03) for the S0 → S3 electronic transitions coefficients.

It is generally accepted that the effect of H-bonding cannot be properly described by the polarizable continuum model (PCM) of the media. Therefore, in this study, the effects of specific solvation in the solute–solvent and solute–solvents binary mixture have been accounted for and simulated considering a composition of compound K1 and one or two solvents bound to the carbonyl oxygen.

The above findings were complemented by NBO theoretical calculations, where we calculated the stabilization energies through hyperconjugation associated with complexation between K1 and one solvent molecule explicitly H-bonded to the in-plane carbonyl lone pair (cf. Figure S3), or two solvents, where the second one intermolecularly H-bonded to the first solvent. The analyses were carried out by examining all possible interactions from the donor carbonyl oxygen lone-pair to the empty σ* hydroxyl O–H or C–H of the solvent.

In the K1-MeOH, we noticed a considerable charge transfer ca. 16.71 kcal mol−1 from lp(1)nC=O and 18.23 kcal mol−1 from lp(2)nC=O to σ*O-H of the alcohol molecule. This is to be compared to only 3.80 kcal mol−1 conjugation in the K1-ACN complex. Furthermore, in the K1-ACN-MeOH these hyperconjugation energies reduce to 3.84 and 2.05 kcal mol−1, respectively.

Commenting on our assignment to the origin of the weak band absorption in the 300–400 nm region, we notice that the S0 → S3 excitation is mainly a HOMO➔LUMO+1 transition 1(π,π* -type), thus excluding any sensitivity of this state to variation in solvent polarity. This indeed is found in the absorption spectra of K1, where the shape of the absorption band at 300–340 nm (assigned to S3 transition) did not change after MeOH addition to K1 in CHX solution. Further evidence is given in the ESP mapped on electron density surface (cf. Fig. S4), where nil contribution is seen on the carbonyl oxygen or the nitrogen groups in the LUMO+1 MOs in nonpolar, as well as polar media. Moreover, our calculations, give the values for the oscillator strengths as f = 0.039, f = 0.037, and f = 0.033 in CHX, ACN and MeOH, respectively. This is in accordance with experimental interpretation of the steady state absorption spectra, where no change in spectral position is seen, rather, the oscillator strength slightly drops in CHX with addition of MeOH (cf. Figure 1a).

Fluorescence study in solvent mixtures

Cyclohexane-methanol (CHX-MeOH) system

Molecules with charge transfer (ICT) character in their excited state, can interact with the surrounding media by many mechanisms, mainly electrostatic and H-bonding [14]. Therefore, solvents capable of donating H-bond can have significant effects on the behavior of molecular systems. Moreover, H-bonding, can preferentially solvate the ICT state affecting the solute’s peak position [39] and excited state life-time [40]. Generally, for any binary mixture, the fluorescence maxima are always between the fluorescence peak positions of the molecule in these two pure solvents.

To gain insight into the excited state competitive interaction between the nonpolar CHX and a polar protic solvent such as methanol, we carried out a titration experiment in the K1 in CHX with different fraction of methanol. This fluorescence titration is displayed in Fig. S5. We noticed enhancement of the emission intensity with small increase in the alcohol fraction in the mixture, apparently due to better solvation of the S1 state by methanol due to higher polarity (εMeOH = 32.7 vs. εCHX = 1.88), followed by a decrease in intensity (quenching) as the amount of methanol is increased in the mixture. As evident in Fig. S5, the decrease of the higher energy band between 420 and 470 nm is accompanied by the appearance and growth of the low-energy band characteristic of emission in neat methanol.

Acetonitrile-methanol (ACN-MeOH) system

Initially, the presence of a slight amount of methanol in the MeOH-ACN mixture of K1 solution caused immediate quenching of the fluorescence as seen in the sudden drop (>50%) in the emission band (cf. Fig. S6). Further addition of methanol caused a more steady decrease in emission intensity with considerable broadening of the spectra, and no change in peak position.

This immediate deactivation by the presence of a small amount of methanol in the mixture suggests that the effect is dynamic in nature. This is evident in the I0/I vs. [Q] depicted in Fig. S7, which obeys the Stern–Volmer relationship [41], with R2 = 0.992. However, in the MeOH-H2O system the quenching does not follow the simple straight-line equation but rather gives an upward curving plot because of the involvement of quenchers. Moreover, the diminished emission intensity is probably caused by opening some deactivation channel, such as ISC by complexation with the carbonyl motif [42, 43, 44].

Our TD-DFT calculations show that the S1/T1 gap in the K1-ACN complex is 0.979 eV, and upon attachment of one MeOH molecules to the K1-ACN (binary K1-ACN-MeOH) (cf. Fig. S3), this energy separation drops slightly to 0.969 eV. However, in the K1-MeOH arrangement, this gap slightly decreases further to 0.926 eV. Since S1 is 1(π,π*) in nature and T1 is 1(n,π*), it is anticipated that quenching via intersystem crossing (ISC) is a possible channel. Furthermore, we notice that the S2/S1 energy gap in the K1-ACN configuration is ca. 0.316 eV and becomes 0.395 eV in the K1-ACN-MeOH arrangement and increases to 0.629 eV in the K1-MeOH complex. These results imply that the likelihood of energy borrowing from higher states diminishes with addition of alcohol molecules to the K1-ACN mixture.

The accepted criteria for a H-bond according to IUPAC definition are, (i) O/N⋯H distance should be < 2.650 Å, (ii) O/N⋯H angle is > 120°. The B3LYP optimized minimum structure of the K1-ACN-MeOH system shows that the C=O⋯H–(CH2–CN) distance is 2.223 Å, and the C=O⋯H–C angle is 156.373°, indicating the occurrence of H-bonding. This structure is further stabilized by another H-bond between the solute nitrogen (N39) (cf. Fig. S3) and the phenyl hydrogen N39⋯H24-ph, with a distance ca. 2.611 Å and a H-bond angle of ca. 171.237°.

In the K1-MeOH complex, the H-bond is established strongly as the calculated C=O⋯H34–O42 distance is shortened to 1.849 Å and the angle becomes 172.372°. On the other hand, the solvent’s oxygen is involved in forming another H-bond with the central alkene-hydrogen (H34), ca. distance of 2.384 Å and angle of 131.938 Å. Our interpretation for the stronger H-bond in K1-MeOH structure, compared to the K1-ACN system, is due to better solvation of the structure through charge migration from the C=O oxygen lone-pair. Our NBO calculations (as indicated earlier), revealed that the two O16 lone-pairs, lp(1) and lp(2) transfer 16.71 kcal mol−1 and 18.23 kcal mol−1 to σ*(H37-O42) in the K1-MeOH complex, respectively, whereas this stability is only 3.80 kcal mol−1 from lp(1)O16 to σ*(H-C) in the K1-ACN system. This is a clear indication that MeOH becomes better bound to the C=O motif, and the charge migration will facilitate better energy quenching of the excited state due to better stabilization of the structure.

Moreover, we also notice that in the K1-ACN-MeOH binary arrangement, in comparison to K1-ACN and K1-MeOH, attachment of one MeOH increases the strength between ACN and the carbonyl (C=O⋯H–CH2–CN–MeOH, d = 2.1919 Å) compared to C=O⋯H–CH2–CN (d = 2.223 Å). Furthermore, the stabilization energy (E2(i,j)) from C=O16 to σ*(H–CH2–CN) increases slightly from 3.80 kcal mol−1 (K1-ACN) to 3.84 kcal mol−1 (K1-ACN-MeOH), respectively (cf. Figure S3). H-bonding angle also increases from 148.681° to 156.373° in the binary arrangement due to stronger stabilization.

Furthermore, we find that in the calculated K1-ACN-MeOH system, there is a huge energy stabilization from acetonitrile nitrogen (CH3–C≡N38) to the σ*(H45-O44) of the MeOH (ca. 10.86 kcal mol−1), with almost no change in stabilization from C=O lone-pair to the bonded H42–C40 of acetonitrile (ca. 3.84 and 2.05 kcal mol−1, from lp(1) and lp(2) lone pairs, respectively). Careful analysis of Fig. S3 reveals that attachment of a single MeOH molecule to the K1-ACN cluster, creates a strong H-bond between N38 of ACN and H45 of MeOH (dN…H = 2.0440 Å), with H-bond angle of ca. 174.857°. These findings indicate establishment of cooperative charge migration from ACN to MeOH and explains the sudden quenching with the initial small addition of MeOH to the existing ACN micro-solvated K1.

We also calculated the interaction energies for the K1-solvent(s) arrangement using the following equation:

where EK1-solv, is the ground state minimum energy for the solute–solvent(s) complexes, whereas EK1 and Esol, were taken as single-point energies for the unrelaxed individual solute or solvent(s) in the complex without the solvent(s) or the solute, respectively. The results for the interaction energies support the NBO analysis, and these results are depicted in Fig. S8.

The calculated Ei were between −5.4 and −8.2 kcal mol−1 for the K1-solvent complexes and between −9.7 and −34.8 kcal mol−1 for the binary K1-solvent1-solv2 arrangements. Thus, the interaction energy is more favored in the case of binary systems involving methanol.

The steady quenching of the fluorescence with increase in alcohol ratio in the measured emission spectra is thus explained on the basis that complete H-bonding of alcohol molecules with C=O promotes further radiationless deactivation. As we indicated earlier the S1/T1 gap in these arrangements decreases in the order: K1-ACN (0.9795 eV > K1-ACN-MeOH (0.9690 eV > K1-MeOH (0.9262 eV) (cf. Table 3). Therefore, C=O···MeOH inter-molecular H-bond decreases the S1/T1 energy separation and thus opens up a radiationless channel.

Methanol-H2O binary system

Addition of H2O to a solution of K1 in MeOH caused the emission intensity to decrease steadily, with peak shift to lower energy and broadening of the spectrum (cf. Fig. S9). To explain this phenomenon, we also carried out NBO calculations on the K1-MeOH-H2O complexation.

In this regard, our NBO analysis of the K1-MeOH, K1-MeOH-H2O, and K1-H2O configurations showed a decrease in the amount of charge-transfer for lp(1) nC=O and lp(2) nC=O (K1) to σ*H37-O42 (MeOH) (cf. Fig. S3) from 16.71 and 18.23 kcal mol−1 in the K1-MeOH complex to 11.20 and 4.15 kcal mol−1 in the K1-MeOH-H2O binary, respectively. Furthermore, we noticed an increase in the C=O…H–O H-bond distance from 1.84966 Å to 1.85229 Å, when one H2O molecule is attached to the MeOH-K1 complex.

In the K1-H2O configuration, the charge contribution of the two O16 lone-pairs becomes ca. 7.417 k cal mol−1 and 9.38 k cal mol−1, respectively. The solvent forms a second H-bond with the K1-C17-H43 and transfers ~0.05 kcal mol−1 to the molecule’s C17–H43 (in K1-MeOH) and from water’s O38 ca. 2.10 mkcal ol−1 (in K1-MeOH-H2O) and ca. 1.48 kcal mol−1 from H2O38 in the K1-H2O arrangement.

We notice that in the K1-MeOH-H2O complex there is a considerable charge-transfer (ca. 17.45 kcal mol−1) from methanol’s O41 to the σ* O38-H40 of the water molecule. This is reflected in the overall interaction energy of this complex ca. 34.8 kcal mol−1 (cf. Fig. S8). Moreover, the addition of water to the K1-MeOH complex decreases the S2/S1 gap from 0.6289 eV (K1-MeOH) to 0.5225 eV (K1-MeOH-H2O), and this gap further shrinks to 0.391 eV in the K1-H2O complex (cf. Table 3).

Thus, it appears that the initial addition of water weakens the already established H-bond. However, the H-bond between K1 and H2O in K1-H2O is comparable to the one in K1-MeOH (compare dO…H = 1.8496 Å vs 1.8491 Å and C11-O16-H37 angle of 131.938° vs. 171.071° for the K1-MeOH and K1-H2O, respectively). Once again, similar interaction energies were found (cf. Fig. S8). However, the emission in H2O becomes weaker (more quenching) compared to MeOH. We believe that in the K1-H2O case, crossing from S1 1(π,π*; bright) to the S2 1(n,π*; dark) is responsible for this weak emission because a direct impact of low S2/S1 gap (ca. 0.391 eV) facilitates this crossing. Interestingly, the S3/S1 separation is found to be the lowest in the case of solvation by pure H2O or as a co-solvent.

Conclusions

Compound K1 of the type D–A cycloalkanone studied here, shows strong fluorescence emission in nonpolar as well as in polar aprotic solvents. However, in polar protic media, emission is weak. The emission of compound K1 in neat acetonitrile is highly quenched in the presence of small amounts of protic solvent, such as methanol. Furthermore, emission intensity of the binary system is dramatically decreased in the presence of water in the mixture.

Quantum chemical calculations, based on DFT and NBO, were performed for identification of C=O…HO and –CN…HO H-bond interactions in the K1-solvent(s) system(s) and elucidate the strength of these interactions.

The calculated data of the modeled K1-solvent1 and K1-solvent2 or the binary K1-solvent1-solv2 configurations confirm involvement of inter-molecular H-bonding with the carbonyl C=O motif in the fate of the emission (quenching). These close encounters facilitate the intersystem crossing (ISC) process by reducing the S1/T1 energy gap, which opens a deactivation channel. The weak fluorescence in methanol becomes much weaker (quenched) in water. The explanation is that the later solvent enhances another deactivation pathway through internal conversion between S1 (bright) state and S2 (dark) state due to the proximity of these states.

References

Bures F (2014) Fundamental aspects of property tuning in push-pull molecules. RSC Adv 4:58826

Anto RJ, Sukumavana K, Kuttana G, Raob MNA, Subbarajue V, Kuttana R (1995) Anticancer and antioxidant activity of synthetic chalcones and related compounds. Cancer Lett 97:33

Herevicia F, Ferrandiz MI, Ubeda A, Dominguez JN, Charris JE, Lobo GM, Alcaraz MJ (1998) Synthesis and anti-inflammatory activity of chalcone derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 8:1169

Wu JH, Wang XH, Yi YH (2003) Anti-AIDS agents 54. A potent anti-HIV chalcone and flavonoids from genus Desmos. Biorg Med Chem Lett 13:1813

Liu M, Wilairat P, Go MI (2001) Antimalarial Alkoxylated and hydroxylated Chalones: structure−activity relationship analysis. J Med Chem 44:4443

Sarojinia BK, Narayanab B, Ashalathab BV, Indirac J, KLobo KG (2006) Synthesis, crystal growth and studies on non-linear optical property of new chalcones. J Cryst Growth 295: 54

Shettigar S, Chandrasekharan K, Umesh G, Sarojini BK, Narayana B (2006) Studies on nonlinear optical parameters of bis-chalcone derivatives doped polymer. Polymer 47:3565

Patila PS, Dharmaprakash SM, Funb HK, Karthikeyan MS (2006) Synthesis, growth, and characterization of 4-OCH3-4′-Nitrochalcone single crystal: a potential NLO material. J Cryst Growth 297:111

Ravindra HJ, Chandaraskharan K, Harrison WTA, Dharamaprakash SM (2009) Structure and NLO property relationship in a novel chalcone co-crystal. Appl Phys B Lasers Opt 94:503

Fried SD, Bagchi S, Boxer SG (2013) Measuring electrostatic fields in both hydrogen bonding and non-hydrogen bonding environments using carbonyl vibrational probes. J Am Chem Soc 135(30):11181–11192

Zhao G-J, Han K-L (2009) Role of intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonding in both singlet and triplet excited states of Aminofluorenones on internal conversion, intersystem crossing, and twisted intramolecular charge transfer. J Phys Chem A 113(52):14329–14335

Bautista JA, Connors RE, Raju BB, Hiller RG, Sharples FP, Gosztola D, Wasielewski MR, Frank HA (1999) Excited state properties of Peridinin: observation of a solvent dependence of the lowest excited singlet state lifetime and spectral behavior unique among carotenoids. J Phys Chem B 103:8751–8758

Irene CM, Kwan XM, Gang W (2007) Probing hydrogen bonding and ion-carbonyl interactions by solid- spectroscopy: G-ribbon and G-quartet. J Am Chem Soc 129:2398–2407

Haldar T, Bagchi S (2016a) Electrostatic interaction are key to C=O n-π* shifts: an experimental proof. J. Phys. Lett. 7:2270–2275

Patrick G. (2017) An Introduction to Medicinal Chemistry , 6th edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Stefanisinova M, Tomekova V, Kozurkova M, Ostro A, Marekova M (2011) Study of DNA interaction with cyclic Chalcone derivatives by Spectroscpic techniques. Spectrochim. Acta A 81:666–671

Yang X, Shen G, Yu R (1999) Microchem J 62:394–404

Al-Ansari IAZ (2016) Physicochemical properties of derivatives of N,N-Dimethylamino-cyclic-chalcones: experimental and theoretical study. Chemistry Select 1:2935–2944

Marcus Y (2002) Solvent mixtures: properties and selective solvation. CRC, Boca Raton

Becke AD (1993) Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J Chem Phys 98:5648

Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG (1988) Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys Rev B 37:785

Ditchfield R, Hehre W, Pople J (1971) Self-Consistant molecular-orbital methods. IX. An extended Gaussian type basis for molecular orbital studies of organic molecules. J Chem Phys 54:724–728

Jennifer MR, Jennifer MH, William AM, Robert CC, Erin S, Diego T, Amandra JM (2017). J Photochem Photobiol A: Chem 337:207–215

Sheng Y, Leszczynski J, Garacia A, Rosario R, Gust D, Springer J (2004) J Phys Chem B 108:16233–16243

Holmen A, Broo A (1995) Int J Quantum Chem 22:113–122

Lange AW, Herbert JM (2010) Polarizable continuum reaction-field solvation models affording smooth potential energy surfaces. J Phys Chem Lett 1:556–561

Casida ME (1995) In: Chong DP (ed.) Recent Advances in Computational Chemistry, vol 1. World Scientific, Singapore

Reed AE, Curtiss LA, Weinhold F (1988) Intermolecular 577 interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem Rev 88:899–926

Weinhold F (1998) Encyclopedia of computational chemistry. In: Rague-Schleyer PV, Allinger NL, Kollman PA, Clark T, Schaefer III HF, Gasteiger J, Schreiner PR (eds), vol 3. Wiley, Chichester, pp 1792–1811

Weinhold F, Landis CR (2001) Chem Educ Res Pract Eur 2:91–104

Weinhold F, Landis CR (2005) Valency and bonding: a natural bond orbital donor-acceptor perspective. Cambridge University Press, New York

Glendening DE, Badenhoop JK, Reed AE, Carpenter J, Bohmann JA, Morales CM, Landis CR, Weinhold F (2013) NBO-6. Theoretical chemistry institute, University of Wisconsin, Madison

Frisch M, Trucks G, Schlegel H, Scuseria G, Robb M, Cheeseman J, Scalmani G, Barone V, Petersson GJ, et al (2016) Gaussian 16, revision A.03. Gaussian Inc., Wallingford

Dennington R, Keith TA, aMillam JM (2016) GaussView, Version 6. Semichem Inc., Shawnee Mission

van Duijnen PT, de Vries AH (1996) Direct reaction fields forces: a consistent way to connect and combine quantum chemical and classical descriptions of molecules. Int J Quantum Chem 60:1111–1132

Haldar T, Bagchi S (2016b) Electrostatic interactions are key to C═O n-π* shifts: an experimental proof. J Phys Chem Lett 7:2270–2275

Ito M, Inuzuka K, Imanishi S (1960) Effect of solvent on n,* absorption spectra of ketones. J Am Chem Soc 82:1317–1322

Mc Rae EG (1957) Theory of solvents on molecular electronic spectra-frequency shifts. J Phys Chem 61:562–572

Brealey GJ, Kasha M (1955) The role of hydrogen bonding in the n→π* blue-shift phenomenon. J Am Chem Soc 77:4462–4468

Hirai S, Banno M, Ohta K, Palit DK, Tominaga KK (2007) Vibrational dynamics of the CO stretching mode of 9-fluorenone in alcohol solution. Chem Phys Lett 450:44

Lakowicz JR (2006) Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy, 3rd edn. Springer, New York, p 954

Alty IG, Abelt CJ (2017) Steroelectronic of the hydrogen-bond induced quenching of 3-Aminofluorenones. J Phys Chem A 121:5110–5115

Green AM, Anelt CJ (2015) Dual-sensor fluorescent probes of surfactant-induced unfolding of human serum albumin. J Phys Chem B 119:3912–3919

Nikitina YY, Iqbal ES, Yoon HJ, Abelt CJ (2013) Preferential solvation in carbonyl-twisted PRODAN derivatives. J Phys Chem A 117:9189–9195

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 40132 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Ansari, I.A.Z. The electronic origin of the ground state spectral features and excited state deactivation in cycloalkanones: the role of intermolecular H-bonding in neat and binary mixtures of solvents. J Mol Model 25, 133 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-019-4015-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-019-4015-6