Abstract

Mementoes act as emotional companions that anchor stories. Older adults typically have a rich knowledge of family mementoes. However, storytelling and preservation of mementoes are still problematic for them: their mementoes are still mostly in physical format, which is difficult to share and preserve. Additionally, digital applications and websites for sharing mementoes usually are inaccessible for them. As a result, they spend much time collecting mementoes, but spend less time on telling and recording the related stories. In response to this, we report our study driven by the research questions: Rq1: What are the characteristics of older adults’ intergenerational memento storytelling? And Rq2: In which ways could a tangible display facilitate intergenerational memento storytelling for older adults? We designed a tangible device named Slots-Memento. We first conducted a preliminary evaluation to refine the prototype. In the field study, eight pairs of participants (each pair consisting of an older adult and his/her child) were recruited to use the prototype for around 1 week. Semi-structured interviews were then conducted both with the older adults and their children. Subsequently, mementoes collected were categorized and analyzed. Stories collected were firstly transcribed, then were conducted with structural and interactional analysis. In the concluding discussion, we present abstract implications for the research questions: two tables summarizing characteristics of their intergenerational memento storytelling, and related strategies of designing a tangible display individually.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Mementoes are objects kept as a reminder of people, places, and experiences. They carry personal symbolic meaning and could be used to privately reflect on the past or share memories [1]. Older adults typically have a rich knowledge of family mementoes, which are highly valued, and support different types of family stories and recollections [2]. Therefore, when the same object was mentioned by young and old, the young connected to it actively, older people contemplatively [3]. Traditionally speaking, mementoes are physical, and sitting together to communicate face-to-face is the most common way to share mementoes [4]. As technology advances, mementoes (especially photos) are increasingly becoming digital [1]. Services for sharing mementoes are plentiful: from sending e-mail to other online applications. Now, we have many opportunities to share mementoes even with people at a distance.

However, sharing mementoes is still problematic for older adults, especially for those living in a nursing home. The first reason is the transition from print to digital media has provoked a generational shift in the curation of memories from physical copies to digital storage mediums. Despite that the young generation has become “Flickr Generation,” handling digital content, most older adults are still so-called Kodak Generation [5], maintaining print photo albums and physical mementoes, which are hard to share and preserve. Second, digital storytelling and online oral history platforms, such as StoryCorps or LegacyStories.org, have been gaining popularity as technology-mediated ways to record family memories. However, our target group is aged, non-tech-savvy people. Internet and social media use drop off significantly for people age 75 and older [6]—even for the Netherlands is a country with high levels of general Internet diffusion, only around 30% of over-75-year-old had a tablet or smartphones [7, 8]. Currently, most interfaces are designed to support younger users. However, this group of older adults is still disconnected from the mainstream social circles due to lack of technology and devices that resonate with them [9]. Third, currently, passing around stacks of paper photographs while sitting around a table seemingly is the only way for older adults to share mementoes, whereas they do not have many such opportunities because they live separately from their children. Dying people hope they will be remembered. However, when death occurs, survivors are left with bundles of images, materials, and objects of the deceased [10], and stories behind mementoes vanish with their owners.

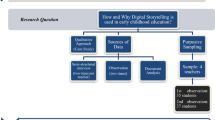

In response to this, we present our study, driven by the research questions: Rq1-What are the characteristics of older adults’ intergenerational memento storytelling? And Rq2-In which ways could a tangible display facilitate intergenerational memento storytelling for older adults? The research questions are answered by the implementation of a tangible display prototype, mementoes and story analysis, and their using reflections.

The contributions and features of this paper are as follows. First, we see memento sharing a cooperation process that both the storytellers and listeners should actively involve. We particularly investigate and answer how the young generation could participate: they are not only the audiences of the storyteller (older adults), but also on the memory trigger provider, acting as “filter” and “selector” of mementoes. Second, we focus not only on the mementoes themselves, but also on the behind stories. To answer Rq1, we analyze the stories by structural and interactional analysis. The structural analysis helps us to summarize four story structural types, with different narrative patterns, from plenty of stories. The interactional analysis concludes the two features of sharing mementoes face-to-face. Third, to answer Rq2, a framework is constructed, which break the intergenerational memento storytelling into four processes: trigger, telling, sharing, and curating. We then propose related design considerations based on this framework. Figure 1 shows the paper structure.

2 Related work

Memento is a research topic that receives attention from diverse perspectives. This is a multidisciplinary area, and we focus on the literature in the HCI area. For clarity, we organize them into two sub-sections, scope, and functions of mementoes, focusing on theoretical aspects, and ethnographic studies and applications, focusing on practical aspects.

2.1 Scope and functions of memento

Memento is defined as an object given or deliberately kept as a reminder of a person, place or event [11]. The orientation towards objects can be sources of the self, relational intimacy, and social integration [12]. Mementoes, such as keepsakes, postcards, souvenirs, trinkets, and other similar items as physical objects, symbolize and evoke memories, associations, and stories. Photos are also mementoes, allowing memories to be shared across time, place, and people [13]. Now mementoes (especially photos) are increasingly becoming digital, replacing traditional physical forms such as paper documents, letters, etc. [14]. From the perspective of mementoes themselves, they play an essential role as triggers for personal memory. Recalling memories of mementoes is a process of reminiscence, which improves psychological well-being and helps older adults find meaning in their life [15]. From a social perspective, stories told by older adults create meaning beyond the individual and provide a sense of self through historical time and in relation to family members, and thus may facilitate positive identity [16]. From a broader perspective, mementoes and related stories are an essential part of identity preservation. Preserving legacy, sharing narratives of events and experiences are the key motivations for families to take photos and display them at home [17].

2.2 Memento practices

There are some ethnographic studies on physical mementoes. Daniela Petrelli et al. report a fieldwork study, describing how and why particular objects become mementoes [11]. Similarly, David Kirk et al. explore why and how those objects are kept and archived within the home [18]. Both of these two studies’ research method is conducting family tours and interviews in the participants’ homes. As mentioned, memento is a broad concept. Therefore, different types of mementoes are investigated: Richard Banks et al.’s study focuses on heirlooms, and they investigated the role technology played as part of the process of inheritance [19]. More studies focus on photos: Chalfen et al. acknowledge the central role of film photography in family representation and draws attention to how familial and domestic conventions are reproduced through its tools and practices [20]. Swan and Taylor’s related field study points out that photo displays play into the shaping of a moral character to the home [21]. As mementoes are increasingly becoming digital, some fieldwork looks at characterizing and comparing physical and digital mementoes in the home [2]. Connie Golsteijn et al. further investigated how we perceive physical and digital objects, and their advantages and disadvantages [22].

Regarding applications designing for mementoes, some aim at building links between physical mementoes and related audios, which are mostly based on barcodes and RFID technology. “MEMENTO,” an interface that can support the creation of scrapbooks that are both digital and physical in forms [23], a tagging service that provides means to link stories to objects via QR codes and RFID tags [24]. However, current applications focus more on digital mementoes, which could be generalized into the following aspects: first, capturing personal mementoes, which is the so-called lifelogging, aiming to benefit from the advantages of digitally storing memory cues by aiming for “total recall” [25]. The captured data types are various, from pictures [26], sound [27], to videos [28]. The forms of applications are also varied, ranging from tangible devices to wearable devices [29]. Second, organizing and archiving personal mementoes. Given the temptation to capture as much as possible results in vast personal collections scattered over disparate sources [1], applications mostly employ interactive devices, such as an interactive multi-touch tabletop [30], and a projector [31], both aiming to better organizing and retrieving personal digital content. Third, displaying and sharing personal mementoes, which are the most relevant direction to our study, and will be highlighted in this section.

This research direction is based on the fact that people display photos in their homes to share narratives and stimulate social interactions [17]. Most related applications are used within the context of family, aiming at facilitating conversations within family members, whose audiences are nuclear families. Some are in the form of smart/interactive frames. For instance, “Photoswitch” is a digital photo display device with purposefully simple functions to provoke discussion within family members [32], and “Cherish System,” a smart digital photo frames aiding family members social interaction [17]. Others such as an interactive table supporting browsing, sorting, and sharing digital images [33], and a tool that is aiming the use of digital mementoes by using earlier social media posts as emailed prompts for reminiscing [34]. Since these applications are focusing on digital content, their fundamental design guideline is to enable digital content more accessible through designing devices that merge interactivity of physical objects with digital content.

2.3 Storytelling and intergenerational communication

Regarding storytelling, Jasmine Jones et al. interviewed 21 people in “teller (older adults)” or “listener (young adults)” generations in their respective families, aiming to understand how memories were conveyed to future generations through family stories [35]. Some research and applications focus on the dementia group. For example, “Traumreise” explores how tangible objects integrating multisensory digital media could stimulate dementia people to tell stories [36].

Regarding family communication area, several interactive products and systems have been proposed to support communication in families. There are applications supporting co-present sharing, for example, “Cueb” is a set of interactive digital photo cubes with which parents and teenagers can explore individual and shared experiences and are triggered to exchange stories [37]. For the family members over a distance, Tejinder K. Judge et al. explore how families would make use of a video system that permitted sharing everyday life over extended periods between multiple locations. There are studies focusing on enhancing communication within remote family members through sharing photos [38, 39], and there are also applications aiming to strengthen family connectivity through ambient awareness [40]. Another study explores how older adults’ favorite objects (for example, kettle and tea box) could be augmented to help them to connect with adult children living remotely [41]. We found most applications for non-tech-savvy older adults adopt tangible interface, which proved to have potential to improve older adults’ technology acceptance. We also use the tangible interface in our research prototype.

Given that one of the most precious characteristics of older adults is their memory of events, people, and places during their childhood and adolescence [42], older adults could be deemed as story content producers. Jenny Waycott et al. further investigate the nature and role of digital content that has been created by older adults in the nursing home, for the purpose of forging new relationships. Their findings demonstrate that older adults are willing to express themselves creatively through digital content production [9]. We build on this idea and extend it into intergenerational memento story sharing.

2.4 Research gap and contribution over previous work

First, through retrieving the definition of memento, we find it a broad concept, and literature has investigated how and why particular objects become mementoes. In other words, previous work pays more attention to mementoes themselves, and behind stories are ignored. Second, little research and design have been particularly paid to senior users. HCI researchers give more attention to personal digital content, while mementoes of older adults are mostly in physical format. Third, currently, most applications related to sharing mementoes are mostly co-present sharing, which is used within the context of nuclear families, that all the family members live together.

In this study, first, we focus on both the mementoes and the behind representations. We analyze the stories by structural and interactional analysis. The structural analysis helps us to summarize four story structural types, with different narrative patterns. Second, we focus on the older adults in nursing homes, who are living separately from their children. Third, we build on the idea that older adults act as story producers, and the younger generation’s role is further highlighted in our study. Our study investigates what roles could their children play in the memento storytelling of the older adults: they are not only the audiences of the storyteller (older adults), but also be the memory trigger (mementoes) provider, acting as “filter” and “selector” of mementoes. Finally, we construct an intergenerational memento storytelling framework, which breaks the intergenerational memento storytelling into four processes: trigger, telling, sharing, and curating.

3 Design intervention

3.1 Prototype: Slots-memento

Research prototype in this paper is based on our previous work [43], whose design process is shown in Fig. 2.

The initial prototype was refined after preliminary evaluation, and the final prototype is shown in Fig. 3. It includes a tangible device and a flash disk, integrating functions of memento photo displaying and story recording. Its interaction and form draw inspiration from slots-machine. The user could pull down/up the handle to switch memento photos and press the button to record stories. The handle operation could offer a more intuitive and enjoyable using experience to this non-tech-savvy user group, as was verified during preliminary evaluation.

Appearance and display interfaces

Its outlining shape is round-cornered, evoking an approachable and ergonomic design. The L-shaped appearance makes the display easy to see, and buttons easy to press. The portable dimension also makes it easy to carry (L = 22 cm, W = 11 cm, H = 17 cm). A 7-in. display and a microphone are arranged on the upside, and a button is on the front side. The lever is positioned on the right side. The main body is made of porcelain white acrylic, and part of it is covered with wood-grained paper, making it look slightly old-fashioned, which is in line with the older adults’ esthetic taste.

It contains two display interfaces: the Photo Interface and Recording Interface. Vintage style is also applied in both the interface elements and fonts. Considering the fading eyesight of older adults, bold and huge fonts are used. There are usage tips at the bottom: note: press “REC/STOP button before/after recording.” The Photo Interface displays one specific memento photo, which could be switched to the next/previous photo by pulling down/pushing up the handle. It will be switched to Recoding Interface when pressing the REC/STOP button, in which a dynamic recording icon and timer widget are placed to provide real-time feedback.

The flash disk is used to store memento photos and story audios, and it is embedded in a Medium-density fibreboard (MDF)-made shell. Our original plan was to make the data transmission wireless. For example, sending them in the forms of emails to the young. However, the audios and image files recorded by Raspberry Pi were too large to make the sending process stable. Using flash disk is actually a trade-off considering the stability of the prototype running.

Hardware

It consists of a Raspberry Pi, a 7-in. display, a joystick, lever, portable battery, microphone, audio adapter, and a button (Fig. 3). Raspberry Pi 2 Model B is chosen as the hardware platform, and Joystick USB Encoder board is the medium to connect Raspberry Pi and joystick. The lever is 3D printed, which could fit into the joystick component. Assembly of microphone and sound-card provides audio input, and the LCD Screen is graphical output. A power bank powers the prototype.

4 Field study

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Procedure and method

We recruited eight pairs of participants (each pair consisted of an old adult and his/her children). The older adults were from two nursing homes in the Netherlands. During the weeklong deployment, interviews were conducted at the beginning and the end. Three same prototypes were made, and each set was provided with a paper instruction for use. The basis for providing paper manuals is that older adults in the nursing home relied heavily on paper and preferred physical interaction, which is found in the pre-study interview. The instructions in paper manuals are static, which matched their learning style. Detailed procedure is shown in Fig. 4. In step 1, we first introduced the research purpose and process. We then explained the concept of “memento” to the participants and gave them some example pictures of mementoes (souvenirs, albums, paintings, etc.). We then asked them to sign formal consent forms. In step 2, the pre-study interview was conducted, consisting of a guided tour and a semi-structured interview. In step 3, we showed them the prototype and usage scenarios and gave them a short hands-on tutorial on how to use. Then each pair used the prototype for around 1 week. We did not set the minimum/maximum number of captured mementoes for each pair of participants. However, we did encourage them to capture as many as possible. We also did not set the restriction of who chose the mementoes. In most cases, the young chose mementoes to ask the older adults. While if the older adults had a strong desire to share some mementoes, they asked his/her child to capture those mementoes. The reasonability of our deployment duration was twofold. First, it is based on related literature [44]. Second, we collected a sufficient quantity of mementoes and stories during the weeklong deployment, and 1 week was adequate to determine if the prototype was accepted by the participants. In step 4, we conducted the post-study interview. The primary source of evidence in our analysis included photo records of mementoes gathered in their homes, audio records kept of all interviews with participants, as well as the handwritten notes, which were taken during the interviews and guided tour. All names and data reported in this paper have been anonymized, and we restricted access to the data to our research team only. We also made small edits in part of the quotes for clarity.

4.1.2 Interview data analysis

Grounded theory techniques [45] were adopted to analyze the interview data, so as to allow themes to emerge from them in a bottom-up manner. The basis for we adopt this method was because of the wide and open-ended nature of the interview content. Interview transcriptions of each participant (senior and young) were coded, respectively. We have provided an example coding process in Table 1. In the Initial coding, we remain open to find whatever theoretical possibilities we could discern from the raw data. While in the Focused coding, we chose a set of central codes from the dataset, which finally result in the identification of themes.

4.1.3 Participants

Older participants were recruited by the caregivers’ recommendations in nursing homes. Our recruiting criteria were as follows: first, no significant physical impairments (including cognitive impairments such as dementia and Alzheimer); second, own a certain number of mementoes and are willing to share them for research purposes, on an anonymous basis. The older participants spanned a range of previous occupations (nurse, teacher, etc.) and ages (ranged from 73 to 87), providing a range of perspectives. As we aim to deem the older adults as memento story producers, we only provided demographic information of the older adults and their children. Their descriptions (Appendix Table 5) cover the following aspects: basic information (age, previous job, marriage status), familiarity with technology, habits of keeping family mementoes, interests, and their intergenerational connections. According to our investigation, older adults in the nursing home are highly representative of “Kodak Culture” photography, as opposed to users heavily focused on online communities [46].

4.1.4 Pre-study and post-study interview

The pre-study interviews allowed us to understand how they currently share, manage, and preserve mementoes, which were held in the participants’ homes, allowing them to describe their routines for memento storage and sharing in context. It consisted of a guided tour and a semi-structured interview. In the guided tour, we asked them to arrange a brief guided tour of their homes, aiming to examine their mementoes for displaying and stored in hidden places. With their permissions, we entered their rooms (excluding private or inaccessible rooms), and we took photographs and notes. We then conducted interviews, and topics are shown in the Appendix Table 11. While the post-study interview aimed at asking them to reflect on their use of prototype, and topics are shown in the Appendix Table 12.

4.2 Findings of pre-study: current memento storytelling situation

4.2.1 Background information: familiarity with technology and connecting with children

Older adults in nursing home acquired information still mainly by traditional tools: newspapers, magazines, TV, etc. Apart from the youngest older participant who had an iPad and used it to browse news, watch videos, and play simple games, the rest did not use computers or smartphones, which was in line with [47]. They had regular contact with their children, who visited them regularly, and frequency ranged from once a week to once a month, and the duration of each visit was 2–4 h. Despite regular visiting, they wanted more. However, their children’s busy work hindered the connection: “I hope they could visit me more, but they are too busy.—P7, F” “When they visit me, sometimes we have dinner together. It is the coziest moment, and I like that.—P2, M” They typically connected by telephone, but they called their children only when in special and urgent situations (festivals, diseases, etc.): “I don’t call my children very often because I don’t want to disturb them, they have to work after all.—P4, F” Children were nearly the only people that older adults could really tell personal things to: “I would like to share personal things with my children and close friends. These were very private. I don’t want to share with others, nor do I think they are interested in.—P3, F.”

4.2.2 The young showed interests in family mementoes, providing potential for our research

Most of the young stated they were interested in their parents/grandparents’ mementoes. They knew some mementoes, but they knew little about the behind stories: “Before my mother moved to the nursing home, some of her belongings were moved to my home. I am curious when organizing them.” However, in most cases, older adults’ mementoes were seemingly ignored by their children, and they realized its importance only when the older adults passed away: “It was only when my father passed away that I realized I didn’t know too much about him. I spent a whole week going through his belongings. I found some photos that I never saw before, and I scanned them.”

4.2.3 What mementoes did the older adults keep?

Object

Forms of their objects were various: souvenir, artifact, trophy, sculpture, and so forth (Fig. 5a) The sources were also various: inheriting from parents, gifts from friends, artifacts of special meaning, souvenirs from traveling, and even artifacts made by themselves, and so forth. However, since most older adults moved home multiple times, some of their artifacts were discarded, or given to their children. Therefore, only a part that was lightweight or precious were still in their possession. Also, rooms in nursing homes were too small to hold all their belongings.

Photo

Their photos were also mostly in physical formats, and they all kept serval albums. Compared with artifacts, photos were more space-saving. Therefore, of all their mementoes, photos were the most that older adults kept. Apart from a small part that were displayed, most were stored in albums, envelopes, and boxes (also found in [4]). We also found the older the photos, the rarer. This was because decades ago, the camera was not as easy to be accessible as now (Fig. 5e). As such, photos of that time were more formal, which was used to preserve for momentous occasions, such as weddings and family portraits. Except one participant left his photos unsorted, the others carefully organized their photos. The albums were of different themes, such as family, traveling, marriage, etc., and photos inside were generally arranged in chronological order: “When we were young, every year we had three weeks outside for travelling. I organized the photos in different albums. I used to spend lots of time on it. It cost too much time. —P5. F” Some older participants needed to refer to the time-stamps to recall memories, which were important clues to recall and search. Some participants added notes, theme tags, or dates on the photo, and one even taped related objects to the photos, such as a piece of rock from the scenic spots, local candy sticks, and maps. In this sense, the affordances that albums provided were not just collections of photos, but carriers of his/her memories (Fig. 5d).

Paper documents

Their paper documents included postcard, letter, certificate, map, and so forth. The certificates and maps were mostly displayed. Postcards and letters were mostly tucked away in storage, either because they were hard to display, or because they were too private (Fig. 5b).

4.2.4 Where did they locate their mementoes?

Overall, mementoes that were a long time ago were located in storage rooms, while unique and private mementoes were located in the bedroom, while more recent mementoes were placed in the study room and living room, which were more accessible. Consistent with previous research [2], we found apart from a fraction were placed on display throughout the home in both formal and informal locations, such as hanging on the wall, displaying on table and shelf, etc., most were stored in hidden places (drawer, closet, shelf, cabinets) (Fig. 5c).

First are mementoes for display. Although decoration styles varied in their homes, they all had a small part of mementoes displayed. For example, photos hanging on the wall, artifacts on shelf and table, etc. Either because the mementoes associated with special meaning (family photos, special gift, favorite inscription, etc.) or because of their artistic values: “These are fish, and I put them here. My daughter bought them for me because she knows I am Pisces.” —P1, F. “Well. For that painting, I just find it beautiful, and that’s why I hang it there, nothing more.” —P6, M.

Second, mementoes stored in hidden places were out of their sights, which made older adults seldom revisited them, not to mention share them with others (Fig. 5c). The older adults gradually forgot them, and that was why the participants showed great surprise when some mementoes were rediscovered in the field study. They mentioned that the primary cause of storing mementoes was space constraints.

4.2.5 In which situations did they share mementoes with their children?

First, mementoes for displaying raised conversations occasionally. They were easily noticeable, which effortlessly evoked conversations with guests. However, this happened only when family members or friends came for visits, which was occasionally and accidental: “Some people come, they see photos of my family, and they would ask: oh, that’s your wife? I will say yes, and start talking my dead wife.—P2, M” Second, only one older participant sometimes said in holidays, the whole family would sit together to look through albums together: “When on holidays, we took out albums and talk about the past, but that happens not often.”—P5, M

4.2.6 What problems did they encounter when sharing memento stories?

First, mementoes for displaying did not fully support personal reminiscence. We thought they were noticeable and could support personal reminiscence. Nevertheless, they stated that those mementoes in home environment were so familiar that they often could not realize their presence. Second, they seemingly ignored mementoes sharing and storytelling. During our interview, when the mementoes were rediscovered, they were excited and naturally immersed in recalling. Despite that they would like to recall, they rarely had chances to talk about the mementoes specifically and deliberately in daily lives, nor did their children ask about that: “I don’t talk about them often, nor do my children ask. Maybe when I am almost dying, they could realize it is time to remember his mother’s stuff.”—P6, F. Distance also hampered the memento story sharing: “Visiting time is short, so we so we couldn’t make time for talking about her photos and souvenirs.” Lastly, the older adults worried that their children might be not interested in their mementoes.

4.2.7 Other: older adults had the desire and demand for preserving lives

Older adults hoped their lives could be remembered. For example, one older participant had filmed a video to document his life: “I recorded a DVD to tell my life. So when I pass away, my children don’t have to do anything, they just need to play it, that’s all.” —P2, M One older participant had made a brief biographical note, in case their children wanted to know him when he passes away. Another older participant had scanned some of the photos.

4.3 Findings of post-study interview

4.3.1 Their feelings and opinions on the prototype

Regarding the senior users, they thought Slots-Memento could facilitate their memento storytelling and recording. They enjoyed telling the memories. The field study helped them to revisit and rediscover their mementoes, some of which were they almost forgot: “It is so good to see these photos again. I almost forgot them. I think the device is really great, because I can put all my stories and emotions into it. —P6, F” They showed interests, especially the direct recording function. Compared with handwriting, they felt audio recording lowered cost of narrative, given that they felt difficulty in writing as they aged: “I wanted to write my stories down, but always don’t feel motivated to that. My eyesight declines. The recording is really helpful.—P4, M”. One unexpected finding was that they appreciated the flash disk as a tangible carrier to preserve their memories. Feedback regarding usability was overall emotionally satisfying. The metaphor of slots-machine and vintage style with decorative effect were understood and accepted. In short, they thought the prototype was simple-functional and easy to understand, the lever was easy to hold and brought interest when using: “The slots-machine-like operation raises me a sense of expecting and curiosity for the unknown photos. It is interesting.” Some argued that when using the prototype, they felt as if they were telling to strangers, and they felt at ease: “I feel like a broadcaster, and I’m telling strangers about my life journey.” They also would like to share their stories with strangers on an anonymous basis. Another motivation for recording the stories was their responsibility of carrying on family history.

Regarding the young participants, overall, although our project increased their burden on capturing mementoes, they showed interests and enthusiasm in their parents’ photos. They expressed willingness to preserve them, despite capturing the large quantity of photos were time-consuming: “The concept of recording stories is meaningful, and it helps to build a connection between the memento and its story counterpart. The recordings are kept easily.” They thanked us for giving them a chance and reminder to pay more attention to parents’ stories. Specifically, first, they learned new things about parents from the audios. Although most young participants knew the existence of the mementoes, they knew little about the stories behind them: “I didn’t know that pipe was from my grandfather, until grandmother told me in the audio.” For those who already knew origins of the mementoes, they understood them from a different perspective: “I know some photos, but now she tells the memories totally from her view.” They also felt the audios contained emotions and familiarities to them, which could convey more information than text, such as emotions, personalities, and feelings. Listening seemed to be more natural. The background sound in the audios also made the young imagine the scene that their parents/grandparents told stories: “I even hear the meow of her cat. So kind.” Therefore, they appreciated the idea of preserving voices because it contributed to the multi-media story: “I ever made a short video consisting of photos to honor my father. I added BGM, but I don’t have his real voices.” Second, the field study made them aware of the importance of preserving older adults’ mementoes and stories, which was currently overlooked. At present, the young did not have many chances to sit together with older adults to specifically listen to their stories: “Occasionally my mother talked about her past stuff, and this device makes me aware of the importance of preserving them. Otherwise, these memories will disappear forever.” Further, they felt the recordings were a treasure to pass on to the next generation: “It is nice to preserve my mother’s stuff, so that I can tell and play them to my children. The audios are a priceless present.”

4.3.2 Their children’s preferences and attitudes towards the stories

The young’s preferences for memento stories were varied, and they had different interests. For example, some were interested in the old photos of family members, which could raise share experiences with the older adults, and exchange feelings: “The photos are about us. The photos are about us. Talking about the past together with parents is better than seeing photos alone.” Some were interested in the grandparents’ souvenirs: “I never saw my grandfather. I am interested in stories about him.”

The young participants frankly mentioned that not all the stories aroused their interests. They had different reactions to different themes. Some were appealing to them, while for those were boring and uninteresting for them, they chose to fast forward, or even skip. Also, the large number of audios and photos increase the cost for organization and curation, and made it hard for subsequent retrieval. Even so, their attitudes towards preserving were conservative, and they preferred to keep them all. The first motivation was they preserved for the future, and even for the next generation. They realized the importance of preserving them after the field study: “Once my mother passes away, my daughter will never have a chance to listen to their grandmother telling stories.” The second motivation was “just in case”. That is, once the content becomes digital, they tend to be conservative in building up extensive collections of materials, as previous literature mentioned: they find it hard to delete materials and defer decisions about keeping the information until they see how and when that information will be used [48].

4.3.3 Comments for improvements

Both the senior and young participants provided valuable comments for improvements. First, the older adults suggested the prototype should be able to keep running, instead of manual power on/off each time, which was inconvenient. Second, by default, it should display the photos as a slideshow when in standby mode, so as to attract their attention, and encourage them to use. Third, adding story playing function, as they hoped to show and play the stories to others. Other suggestions included enlarging the display screen and playing videos, since they also had some family videos. While according to the young, as expected, they mentioned the flash disk transfer was not convenient, and wireless networks should be adopted (Fig. 6).

5 Analysis of mementoes and stories

5.1 Analysis of mementoes

Categorization of mementoes in our study

There are different methods for categorizing mementoes in existing research. The coding scheme constructed by Csikszentmihalyi et al. was developed by analyzing and coding 1694 special objects from over 300 participants from 82 families [49]. However, since it covers a range of everyday objects, such as animals, plants, vehicles, clothes, furniture, etc., it is too over-generalized to apply in our study. While David Kirk et al.’s study divides family mementoes into physical, digital, and hybrid, among which the hybrid objects are physical instantiations of digital content such as cassette tapes, CDs, and vinyl records [18]. However, in our study, almost all the mementoes were in physical formats. Therefore, this categorization is not precise enough for our study either. Physical mementoes need to be further sub-classified.

In our field study, as photos were the most mementoes that older adults kept, photos were classified as one particular category. Ultimately, we classify their mementoes into three main categories: object, paper document, and photo, and 25 sub-categories (Fig. 7). The object is divided into seven sub-categories depending on their source (Gift from friends, inherited from parents, Traveling souvenir, Bought, Self-made, Children’s toy, and Other). Photo is divided into Family member, Marriage, Friends, Festival, Object, Scenery, Graduation, Interesting moment, Animal, Plant, and Other, depending on their themes. Paper document is divided into postcard/letter, Inscription, Map, Flyer, Booklet, and Other, depending on their forms.

The proportion of mementoes

>Totally 283 mementoes were collected (Fig. 7). The average number of captured photos (after removing repeated ones, since one memento might correspond to multiple photos) was 35.4. For clarity, we present this section in the form of “proportion of one memento” (quantitative data) + “reason of telling it” (qualitative data from the interview). Photo was the most popular type accounting for 46.3%, among which “Family member” was the most, and it was consistent with the interview that they mostly preferred to talk about photos of family members and old friends, as well as when they were young. Reasons were twofold: First, moods of nostalgia prevailed among them, and old photos were effective memory triggers for reminiscence of their youth: “The earliest memories were blurred, you cannot recall without the photos. With photos, you could recall memories a long time ago, even the details.”—P8 “When I look through the albums, I see my son grows from a little kid to an adult, I feel time flies.” —P5, F. Second, some of their friends and family members had passed away, and browsing photos was a method to recall and honor them: “Some people on the photos were no longer alive. Whenever I see them, I could go back to that time.” —P5, F. Followed by “Marriage,” which belongs to major life events. Next were friends, festival, etc. 33.2% were Object, among which the most was “Gift from friends,” which could remind them of the relationship with friends. Followed by “Inherited from parents,” which were normally very precious artifacts. They were unique to them, not only because of the value of memento themselves, but also because of the relationships they represent. Next was “Traveling souvenir”, which were of esthetic values. For this type of mementoes, they could only remember where and when they bought, but forgot the reasons and situations: “Maybe I had lots of reasons of buying them, but now I almost forgot, they are now just for decoration.” They seemingly had no much interests in telling them, despite the large quantity number of souvenirs. The reason, one older participant explained: “I want to tell my stories, those (the travelling souvenirs) are other’s stories.” The remaining 20.5% were Paper document, among which “Postcards/letters” were the most. These types of mementoes also represented relationships with the senders. Followed by “Certificates,” including graduation and qualification certificates, of which were they were proud.

The older adults’ usage frequency

We could not extract too much useful information from their usage frequency. As shown in Fig. 8, except participant 4, who used it evenly every day, the rest had a novel effect during using. There were two peaks for most participants. The first peak appeared when they just received the prototype, and the second peak appeared when their children visited them.

5.2 Analysis of stories behind mementoes

In this section, stories were analyzed from two dimensions: structural analysis, emphasizing on the way stories are told, and interactional analysis, emphasizing on the dialogic process between teller and listener. Transcription was based on Robert Miller’s transcription guideline [50], and we also made small edits in part of the audios for clarity. Length of the audios varied between 29 and 270 words after transcription.

5.2.1 Structural analysis

The basis for adopting structural analysis is that narratives are structured, which have plots with both temporal and spatial features [51], and the structure of stories is more stable than the content of stories [26]. We applied Labov’s model [53] to conduct structural analysis, and the first reason is in our case, stories were related to the storyteller and were told in an informal manner, i.e., they are “natural narratives” [54]. While Labov’s model is applicable to “natural narrative” as its origins are situated in the everyday practices of real speakers [55]. Second, most stories collected in our study were single narratives, while Labov’s model is based entirely on a single person—the narrator, without considering the audience [54]. According to Labov’s model, narratives have formal properties, and each has a function. A “fully formed” narrative includes six common elements: Abstract, Orientation, Complicating action, Resolution, Evaluation, and Coda [53] (Fig. 9, left). In our structural analysis, four structure types of stories emerged.

5.2.2 Four structural types of stories in our study

-

1.

The story describing and commenting on the giver. Stories of mementoes received from others (gift, heirloom, postcards, etc.) usually are of this type. Specifically, memento acts as “Abstract,” which is a short description of the memento, such as what it is, what it is for, and where it is from. Since the mementoes are from someone else, the rest of the story turns to describe the giver: such as who the giver is, stories that happened between older adults and the giver. Some stories end directly after the description of the giver, while some end up with “Evaluation” and “Coda,” which are opinions on the giver, or storyteller’s feelings.

-

2.

The story describing the memento itself. This type of artifact includes items that were hand made by the story-tellers, scenic or landscape photos and historical keepsakes. This type is of high descriptive features, rather than narrative. Specifically, the story starts with the memento’s background information (name, origin, location, etc.), acting as Abstract. Followed by a detailed description of the memento’s content, or the making tutorial (self-made artifact), acting as “Orientation,” “Complicating Actions,” and “Resolution.” Some end up with reasons for keeping, acting as “Evaluation” and “Coda.” This type is of knowledge values. Examples include Appendix Table 6F and Table 7D.

-

3.

The story of high narrative features. Stories triggered by photos of festivals, major life events, and impressive moments are of this type. Specifically, memento also acts as “Abstract,” which is a description of the event. Next are details, including identification of the time, place, persons, events, and the final result, acting as “Orientation,” “Complicating Actions.” Finally are comments, feelings, or new reflections, acting as “Evaluation” and “Coda.” One thing to note is photos of interesting moments, which were captured unexpectedly, but they would like to share actively (Appendix Table 8G). Two features of this type are (1) photos usually are series, and stories are continuous; (2) older adults were easily immersed in the recalling, and we could feel their happiness and excitements through their voices. Examples include Appendix Table 8B–H.

-

4.

The story without concrete plots. This type is nontypical and without concrete stories. Certificates, family photos, and traveling souvenirs usually are of this type. Specifically, audios start with a description of the memento, acting as Abstract. However, what follows is not as detailed as the above three types, and finally is the reason or motivation of keeping them, which are highlighted in this type, acting as Evaluation and Coda. Example stories include Appendix Table 6E, Table 7A, and Table 8A.

5.2.3 Summary

Different types of mementoes unlock different memories. Four structural types emerged, which correspond to four deep motivations for keeping the mementoes of the older adults: (1) symbol a relationship with someone else; (2) memento themselves are of high knowledge values (transmitting skills, historical and geographic knowledge, etc.); (3) documenting life, including wedding, graduation, etc.; (4) for special purposes. Such as certificates (his/ her pride), family photos (for honoring), (artifact) family inheritance, and traveling souvenirs (for decoration). Unlike subjective explanations in the interview, these findings were excavated from an objective perspective. Another finding was that compared with objects, stories evoked by photos were more direct and specific. Photos could document moments with more vivid details, while stories evoked by objects were more indirect and implicit, despite the historical and esthetic value they hold.

5.2.4 Interactional analysis

The interactional analysis emphasizes the dialogic process between teller and listener [4]. Labov’s model’s limitation is the basis of monologic narratives. Therefore, interactional analysis is necessary. In our field study, social interaction behaviors occurred in two situations: the young contacted the older adults after listening to the stories, and they used prototype face-to-face. For the former, the storytelling and listening were not simultaneous: the young contacted the older adult after listening to stories either because they wanted to know more details of stories, or they expressed their viewpoints on the stories. While for the latter, audios collected included conversations between them. Either way, intergenerational communications were raised.

Two examples of sharing objects and photos individually are shown in Appendix Table 9 and Table 10. Memento is the starting point of a conversation, and the prototype acts as a conversation topic generator. Storytelling is a process of co-construction, where teller and listener create meaning collaboratively. Two features of sharing mementoes face-to-face could be formulated. First, storytelling gradually turned into a conversation pattern, and the stories were short and fragmented. The listener influenced the storyteller in serval ways: by acting as co-tellers (as in Appendix Table 10, the storyteller and listener co-reminisced), by putting forward trigger questions (in Appendix Table 9, the listener wanted to know more details), and by evaluations (the listener expressed his/her opinion on the stories). Second, since the listener provides instant feedback, the conversations are natural to be irrelevant to the mementoes themselves. The feedback acts as a new memory clue to trigger the storyteller to tell new stories. Take Appendix Table 10 as an example: the co-present photo sharing facilitated the older adult and young adult to relate their memories to each other, leading to a collective remembering, which is a highly communicative process.

6 Discussion

This section is a discussion of the two research questions: Sect. 6.1 reveals the characteristics of older adults’ memento sharing, and the problems they encountered. Section 6.2 proposes corresponding strategies derived from the field study.

6.1 Characteristics of intergenerational memento storytelling for older adults

Early studies have concluded the younger generations’ habits of curating and sharing digital mementoes, who embrace the digital world. We conclude the following characteristics of older adults’ memento storytelling, revealing the differences between the young generation.

Their mementoes were of limited quantity, carefully organized, and strongly treasured, as they had the desire to preserve them. Previous research shows that people tend to nonselectively keep everything when putting digital artifacts into storage [19], and unlimited storage leads people to regard it as a space needing no active management. However, mementoes of older adults in the nursing home were of limited quantity, as their mementoes had been selected, screened, and resettled. Most of them moved home multiple times, and most mementoes were discarded, except the lightweight or precious ones. The limited living space also motivated them to manage mementoes to avoid an unchecked accumulation. Unlike digital mementoes were archived on the computer in disorganized collections of virtual folders [56], older participants carefully organized their mementoes. Maybe one reason is that prints go through a tougher selection than digital ones, while the young do not need to make a strict selection with digital photos [31]. Moreover, we could infer that older adults strongly cherished mementoes from the following detail: adding notes, theme tags, and even objects related to the photos. In this sense, they saw the albums as not just collections of photos, but carriers of their memories. With this in mind, it is understandable why they had the desire of preserving them, and their current preserving methods included: recording DVD, made memoirs, scanning photos, etc.

Older adults’ memento stories could be generalized into four structural types, with different narrative patterns, revealing their motivations for keeping mementoes. The quantity of stories collected in our field study was somewhat large. Through the structural analysis, these stories were generalized into four narrative patterns, corresponding to four motivations for keeping mementoes (Table 2).

Currently, the mementoes could not fully support their reminiscence and storytelling in their daily lives. Reasons are as follows: (1) The majority of mementoes were stored and out of their eyesight, which was seldom re-accessed and was gradually forgotten. (2) Mementoes for displaying were so familiar that they often did not realize the presence of the mementoes. (3) They rarely shared mementoes deliberately in daily lives, nor did their children ask. Reasons were geographical distance and limited visiting duration. (4) Some tried to write the stories, but it was time-consuming, and they felt difficulty in writing as they age.

6.2 Strategies of designing a tangible display for intergenerational memento storytelling for older adults

6.2.1 The process of intergenerational memento story sharing

The process of intergenerational memento story sharing could be concluded (Fig. 10). The older adults act as memento storytellers, due to their abundant knowledge of family mementoes. Their children are listeners, and the memento photos act as memory cues. It could be broken into four steps: Trigger Process (older adults’ recalling), Telling Process (older adults’ memento storytelling), Sharing Process (memento and story sharing), and the upcoming Curating Process (the curation of digital collections).

6.2.2 Design for older adults’ memento reminiscence (trigger process)

Make the digital counterparts as effective complements to the physical mementoes

Physical and digital mementoes have different characteristics. Features of physical mementoes lie in its materialities enabling interactions for people’s reminiscing. The uniqueness and rarity make it more cherishable. Digital memento could be easily copied and shared, but it is hard to support daily reminiscence due to lack of being present in the everyday environment. They are captured and stored but not reviewed [37]. Therefore, digital counterparts could not replace physical mementoes’ richness of physicality and uniqueness. Physicality and digitality are irreplaceable to each other. To exert their respective advantages, we need to make the digital counterparts as an effective complement to combine their individual advantages. Therefore, a digitalization process of physical mementoes is needed, which also contributes to memento preservation. In our case, this process is achieved by the young generation.

Integrating digital mementoes into their daily life through a tangible display

To make them more be part of the everyday environment, instead of storing them in hidden places, we designed the prototype, based on the premise of physical memento digitalization, with the help of their children. Moreover, since the simple digital display could not provide users with material affordances and interactivity, we tried to create display merging the interactivity of physical objects with digital objects, aiming to make digital content more accessible and interactive for the older adults. Specifically, the handle of the prototype aims to lend tangibility to the digital content to allow for more natural interactions. Although the mementoes are digitalized, the device itself is physical, to a certain extent. Our prototype combined the advantages of both the physicality and digitality to some extent. As mentioned by the participants, one of the merit they liked most was its tangibility. First, the prototype was positioned on the desk, occupying space, and acted as an external physical reminder adding to the older adults’ daily landscape. The tangibility could produce deeper engagement than digital materials. Second, one unexpected finding in our field study was that older adults appreciated the flash disk as a tangible carrier to preserve their memories. Its physicality was better in accordance with their cognition of storing. The tangibility seemingly brought them a sense of familiarity and “sureness.”

Facilitate revisiting to the memento photos through slideshow when not in use

Although literature points out that physical objects are much more embedded in the everyday landscape and trigger memories by merely being seen [22], our pre-study interview indicates the simple physicality is not enough. The mementoes in home environment were so familiar that they often did not realize their presence. Therefore, although the prototype itself should be unobtrusive when putting at home, the photos for displaying should be dynamic when in standby mode, to attract the older adults’ attention and encourage them to use. As suggested by the older participants, memento photos could be displayed randomly like a slideshow, acting as involuntary memory cues, to achieve long-term, sustained use.

6.2.3 Design for the older adults’ memento storytelling (telling process)

Making the digital mementoes materially present in their home only supports revisiting their persona content. To facilitate memento storytelling, we need to lower the cost of the storytelling further. Specifically, three considerations are derived.

Improving the immediacy through integrated audio recording

Similar to the situations of young’s storytelling, which is hampered by the lack of immediacy (switch the computer on, navigate the files, and start pc application) [37]. Our interview indicates that although some older adults had the desire of writing stories, they were hindered by the heavy load of writing. Direct speaking is more natural than handwriting. Moreover, the strategy of “integrated capture” is adopted in our prototype, where interaction with objects that are a natural part of the activity initiates capture of that moment [44]. To be specific, the stories told by the older adults are recorded by a simple press operation, offering a “seamless connection” between viewing memento photos and storytelling. The behaviour of recording audio is also less likely to intrude and disrupt the moment than other forms of capture.

Adopting audio as the storage medium could reach the balance between retaining information and leaving room for imagination

In our context, audio is the optimum story form between text, audio, and video. Reasons are twofold, first, compared with text, audio contains emotions, personalities, and feelings, conveying more information than text alone. The audio could evoke a deeper reminiscence and emotional response, since the sound draws the listener more into the recorded moment [44]. Second, audio shows advantages over video. Psychologically speaking, the video is a hot medium containing a higher density of information, requiring the viewer to do less interpretive work to understand [57]. Video is too real to allow room for thinking and talking about the past with others [20]. According to the young participants, viewing the mementoes while listening to the audios gave them space for imagination and reminiscence. Although the previous study has reported that sounds are ideal materials to enrich digital photography [58], the ambient sound was emphasized by the young participants, in our field study. The sound made the young imagine the scenarios of the storyteller’s storytelling by rendering the atmosphere and enhancing familiarity.

Enhance integrality of stories by providing “Five Ws”

In our field study, the length of audio recordings varied (between 29 and 270 words after transcription). Although memento photos were effective memory triggers to facilitate their recall, some stories they told were not detailed enough. Therefore, to make the stories more detailed and with more plots, another form of memory trigger—“Five Ws” questions could be adopted. “Five Ws” constitutes a formula for getting the complete story on a subject [59]. According to its principle, a narrative could be considered complete if it answers these questions starting with the following interrogative sentences: Who was involved? What happened? Where did it take place? When did it take place? Why did that happen? And How did it happen? [59]. One thing to note is since the “Five Ws” is typically applied in writing and problem solving, the validity of using in storytelling needs to be verified. Furthermore, adding formula to the storytelling process might influence their natural structure and be perceived as a load rather than an enjoyable talking. Therefore, the “Five Ws” in our case is complementary rather than forcing. Older adults could use them as prompt if necessary.

Using it separately makes stories complete and eliminate the interplay between interviewer and interviewees; using it face-to-face is a conversation topic generator

Previous research has revealed two critical functions of mementoes: stimulating conversations with others, and symbols of the past to trigger memories [49] [1]. Using the prototype face-to-face and separately plays these two functions, respectively. When using face-to-face, the prototype is a “conversation topic generator.” It is a natural chat, and the storytelling serves for conversations: the young act as the listener and provides instant feedback. The storyteller must monitor the reaction of the audience, and ensure them stays engaged by appealing to their attention. Therefore, the audiorecordings are conversations full of fragmented stories. While using separately is asynchronous. Storytellers could completely immerse their minds in recalling, and more profound reflections emerged. As such, the stories are complete.

6.2.4 Design for the older adults’ memento story sharing (sharing process)

Coordinate the interests of two generations to avoid aimless memento capture

First, the intergenerational memento story sharing should be better initiated by the young, considering that the older adults had the concern that their stories were not appealing to others. Specifically, we found that although most young participants showed interest in family mementoes, the older adults were filled with ambivalence. For one thing, they would like to tell stories to their children, either because they hoped to be remembered, or because they felt the responsibility of carrying on family history. For another, they worried their children were not interested in their stories. They did not want to bother their children, nor did they want to force them to listen. Therefore, there actually exists a gap between the two generations regarding memento story sharing, which needs to be bridged. Second, we need to coordinate the two generations’ interests. As mentioned in the post-study interview, the young generation were not interested in all the stories told by their parents. In order to avoid blind and aimless mementoes capture, not only the older adults could choose what mementoes to share, but also the young could choose what mementoes to digitalize.

The listener could not only be the audience but also be the memory trigger provider

The roles of the story listeners (the young) are highlighted in our study. Although the literature indicates the importance of listeners’ roles, pointing that story sharing is a collaboration process requiring the participation of both storyteller and story listener, and it makes sense only when both old and young generations participate and engage in [9, 52]. Our research further points that the story listener could not only be the audience but also be the memory trigger provider (mementoes in our case), acting as “filter” and “selector” of mementoes. The overall memento story sharing is achieved in a generation cooperation manner, and during which process, the older adults gain a sense of satisfaction and fulfillment, while their children understand the family better.

6.2.5 Upcoming problem: curation of the digital content (curating process)

The transition of the memento curators after the physical mementoes become digital

The responsibility of organizing the family’s mementoes is taken on by a family’s primary organizer, who also has a great deal of knowledge of what photos are available within the family’s collection [60]. Generally speaking, older adults were the family’s primary capturer and organizers, who had the most knowledge of what photos had been captured, and what mementoes had been collected [60]. However, after the mementoes are digitalized, together with the audios, they are organized by the young. In this sense, the young act as the curator/ primary photo organizer of digital counterparts (digital photo and audio). Roles of the young adds another layer: the curator of the digital collections.

Three directions of curation retrieval digital content in the future

The accumulation of digital content will inevitably bring overwhelming experiences, putting pressure on the organization, and managing the digital collections. Although most young participants state they would make good use of the digital content and treasure them, currently, they are in a state of overload due to a lack of curation of digital content [38]. Collecting serves little purpose without retrieval. Therefore, curation and easy retrieval are two critical issues. Based on the feedback and literature, three directions could be derived:

First, facilitate curation through metadata. Curating digital content with the aid of metadata is not new. Digital collections contain metadata (information about the time, location, duration, and so forth), which could be clustered according to parameters in the metadata [61]. Despite that not all the metadata are available in our case, the metadata could reduce the burdens of management and maintenance to support access and retrieval of digital media. An accompanying system that aiding organize the digital collections could be further developed in the future.

Second, digital collections in our study are raw materials for digital storytelling. Digital storytelling is the process of creating a narrative, with a combination of text, still photographs, audio, and animations [62]. Traditionally speaking, methods of storytelling collection are realized through the interview, and visual images and interview data produce multimodal outputs [63]. Apparently, Slots-Memento contributes to memento story acquisition since it is a memento story collector in a sense. The digital collections could be developed into a multimedia album, or transcribed into text to make a biography, and so forth.

Third, facilitate retrieval by building links between physical mementoes and related audios. Prior research suggests that people like to augment their mementoes with spoken stories, and physical mementoes are logical access points to the digital collection [31]. Therefore, to make easy accessing to digital collections, building links between physical mementoes and related audios could be one option, as discussed in Sect. 2.2.

7 Conclusion

7.1 Answering the research questions

Given the above discussion, we provide the takeaway (Tables 3 and 4) to answer the two research questions.

7.2 Challenge, limitation, and future work

In this study, the first challenge is the recruitment of participants (older adults in the nursing home and their children) that own a certain number of mementoes and are willing to share them for research purpose. Second, this study is hard to be investigated in a lab setting. It is because mementoes studies should go beyond controlled studies since their primary purposes—reminiscing, self-reflection, and sharing of personal experiences—are strongly dependent on subjective perceptions and experiences [1]. The field study puts forward high requirements for the stable running of the prototype.

As for the limitations, regarding the prototype itself, one limitation is that it is an asynchronous communication platform when using separately. As indicated by the participants, the flash disk transfer was not convenient. Therefore, wireless transmission should be adopted in the next iteration. Moreover, it is known from the lifelogging literature that wearable devices with activation/deactivation buttons are usually forgotten and end up capturing sensitive material accidentally. Therefore, the participants in our study might forget recording, especially when using face-to-face. In the future, we could consider applying the acoustic sensor in our prototype: once it detects storyteller’s speaking, it records automatically. Regarding our field study, the design intervention was relatively short term, leading to limited mementoes and stories. As pointed by the participants, organizing, digitalizing, and storytelling of mementoes was a long-term job. The limit usage time is also a threat to validity due to the novelty factor of introducing Slots-Memento for just a week, and a longer deployment duration is necessary. Additionally, our study focused more on the story procurers—older adults’ side, while the young were passive participants.

As for future work, first, particular types of stories (stories related to the same type of memento, for example, postcards) could be compared and explored. Second, the prototype needs to be refined based on feedback from the participants. Third, as discussed, the accumulation of audios is overwhelming over time, we need to optimize the process of the young that provide feedback to older adults after they are listening to the stories. A cellphone application could be developed for them, together with the prototype, making them a complete system.

References

Thudt A, Baur D, Huron S, Carpendale S (2016) Visual mementos: reflecting memories with personal data. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph 22:369–378. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2015.2467831

Petrelli D, Whittaker S (2010) Family memories in the home: contrasting physical and digital mementos. Pers Ubiquit Comput 14:153–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-009-0279-7

Schudson M (1983) The meaning of things: domestic symbols and the self. JSTOR

Frohlich D, Kuchinsky A, Pering C, et al Requirements for Photoware. 10

Kray C, Rohs M, Hook J, Kratz S (2009) Bridging the gap between the Kodak and the Flickr generations: a novel interaction technique for collocated photo sharing. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 67:1060–1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2009.09.006

Zickuhr K, Madden M (2012) Older adults and internet use. Pew Internet & American Life Project 6

Pieters J (2016) More Dutch elderly know how to use the Internet. Retrieved from https://nltimes.nl/2016/12/27/dutch-elderly-know-use-internet

van Deursen AJ, Helsper EJ (2015) A nuanced understanding of Internet use and non-use among the elderly. Eur J Commun 30:171–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323115578059

Waycott J, Vetere F, Pedell S et al (2013) Older adults as digital content producers. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, In, pp 39–48

Unruh DR (1983) Death and personal history: strategies of identity preservation. Soc Probl 30:340–351. https://doi.org/10.2307/800358

Petrelli D, Whittaker S, Brockmeier J (2008) AutoTopography: what can physical mementos tell us about digital memories? Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in computing systems. ACM, In, pp 53–62

Cetina KK (1997) Sociality with objects: social relations in postsocial knowledge societies. Theory, Culture & Society 14:1–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/026327697014004001

Norman DA (2004) Emotional design: why we love (or hate) everyday things. Basic Civitas Books

Nunes M, Greenberg S, Neustaedter C (2008) Sharing digital photographs in the home through physical mementos, souvenirs, and keepsakes. In: Proceedings of the 7th ACM conference on designing interactive systems. ACM, pp 250–260

Driessnack M (2017) “Who are you from?”: the importance of family stories. J Fam Nurs 23:434–449

Fivush R (2011) Intergenerational narratives: how collective family stories relate to adolescents’ emotional well-being. Aurora Revista de Arte, Mídia e Política ISSN 1982-6672:51

Kim J, Zimmerman J Cherish: Smart Digital Photo Frames. 16

Kirk D, Sellen A On Human Remains: Excavating the Home Archive. 10

Banks R, Kirk D, Sellen A A Design Perspective on Three Technology Heirlooms. 30

Chalfen R (1987) Snapshot versions of life. University of Wisconsin Press

Swan L, Taylor AS (2008) Photo displays in the home. In: Proceedings of the 7th ACM conference on designing interactive systems - DIS ‘08. ACM Press, Cape Town, South Africa, pp 261–270

Golsteijn C, van den Hoven E, Frohlich D, Sellen A (2012) Towards a more cherishable digital object. In: proceedings of the designing interactive systems conference on - DIS ‘12. ACM Press, Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom, p 655

West D, Quigley A, Kay J (2007) MEMENTO: a digital-physical scrapbook for memory sharing. Pers Ubiquit Comput 11:313–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-006-0090-7

Barthel R, Leder Mackley K, Hudson-Smith A et al (2013) An internet of old things as an augmented memory system. Pers Ubiquit Comput 17:321–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-011-0496-8

Sellen AJ, Whittaker S (2010) Beyond total capture: a constructive critique of lifelogging. Commun ACM 53:70. https://doi.org/10.1145/1735223.1735243

Sellen AJ, Fogg A, Aitken M et al (2007) Do life-logging technologies support memory for the past?: an experimental study using sensecam. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems. ACM, In, pp 81–90

Petrelli D, Villar N, Kalnikaite V et al (2010) FM radio: family interplay with sonic mementos. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, In, pp 2371–2380

Singhal S, Neustaedter C, Odom W et al (2018) Time-turner: designing for reflection and remembrance of moments in the home. In: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems - CHI ‘18. ACM Press, Montreal QC, Canada, pp 1–14

Jiang S, Zhou P, Li Z, Li M (2017) Memento: an emotion driven lifelogging system with wearables. In: 2017 26th international conference on computer communication and networks (ICCCN). IEEE, Vancouver, BC, Canada, pp 1–9

Kirk DS, Izadi S, Sellen A et al (2010) Opening up the family archive. In: Proceedings of the 2010 ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work - CSCW ‘10. ACM Press, Savannah, Georgia, USA, p 261

Jansen M, van den Hoven E, Frohlich D (2013) Pearl: living media enabled by interactive photo projection. Pers Ubiquit Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-013-0691-x

Durrant A, Taylor AS, Frohlich D, et al (2009) Photo displays and intergenerational relationships in the family home 10

Hilliges O, Baur D, Butz A (2007) Photohelix: browsing, sorting and sharing digital photo collections. In: Second annual IEEE international workshop on horizontal interactive human-computer systems (TABLETOP’07). IEEE, Newport, RI, USA, pp 87–94

Cosley D, Sosik VS, Schultz J et al (2012) Experiences with designing tools for everyday reminiscing. Human–Computer Interaction 27:175–198

Jones J, Ackerman MS (2018) Co-constructing family memory: understanding the intergenerational practices of passing on family stories. ACM Press, pp:1–13

Mertl F, Meißler N, Wiek L et al (2019) “Traumreise” - exploring the use of multisensory digital media in dementia groups. In: Proceedings of the 13th EAI International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare - PervasiveHealth’19. ACM Press, Trento, Italy, pp 189–197

Golsteijn C, van den Hoven E (2013) Facilitating parent-teenager communication through interactive photo cubes. Pers Ubiquit Comput 17:273–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-011-0487-9

Biemans M, van Dijk B, Dadlani P, van Halteren A (2009) Let’s stay in touch: sharing photos for restoring social connectedness between rehabilitants, friends and family. In: Proceeding of the eleventh international ACM SIGACCESS conference on computers and accessibility - ASSETS ‘09. ACM Press, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA, p 179

Mynatt ED, Rowan J, Craighill S, Jacobs A (2001) Digital family portraits: supporting peace of mind for extended family members. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems - CHI ‘01. ACM Press, Seattle, Washington, United States, pp 333–340

Chung H, Lee C-HJ, Selker T (2006) Lover’s cups: drinking interfaces as new communication channels. In: CHI ‘06 extended abstracts on human factors in computing systems - CHI EA ‘06. ACM Press, Canada, p 375

Brereton M, Soro A, Vaisutis K, Roe P (2015) The messaging kettle: prototyping connection over a distance between adult children and older parents. ACM Press, pp:713–716

Dryjanska L (2015) A social psychological approach to cultural heritage: memories of the elderly inhabitants of Rome. J Herit Tour 10:38–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2014.940960

Li C, Hu J, Hengeveld B, Hummels C (2019) Slots-memento: facilitating intergenerational memento storytelling and preservation for the elderly. In: Proceedings of the thirteenth international conference on tangible, embedded, and embodied interaction. ACM, New York, NY, USA, pp 359–366

Jones J, Merritt D, Ackerman MS (2017) KidKeeper: design for capturing audio mementos of everyday life for parents of young children. ACM Press, pp:1864–1875

Corbin J, Strauss A, et al (2008) Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory

Miller AD, Edwards WK (2007) Give and take: a study of consumer photo-sharing culture and practice. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems. Acm, In, pp 347–356

Hunsaker A, Hargittai E (2018) A review of internet use among older adults. New Media Soc 20:3937–3954. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818787348

Whittaker S, Hirschberg J (2001) The character, value, and management of personal paper archives. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) 8:150–170

Csikszentmihalyi M, Halton E (1981) The meaning of things: domestic symbols and the self. Cambridge University Press

Miller RL (1999) Researching life stories and family histories. Sage

Abbott A (1997) Of time and space: the contemporary relevance of the Chicago school. Social Forces 75:1149. https://doi.org/10.2307/2580667