Abstract

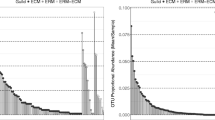

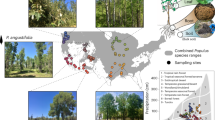

Climate change has important implications on the abundance and range of insect pests in forest ecosystems. We studied responses of root-associated fungal communities to defoliation of mountain birch hosts by a massive geometrid moth outbreak through 454 pyrosequencing of tagged amplicons of the ITS2 rDNA region. We compared fungal diversity and community composition at three levels of moth defoliation (intact control, full defoliation in one season, full defoliation in two or more seasons), replicated in three localities. Defoliation caused dramatic shifts in functional and taxonomic community composition of root-associated fungi. Differentially defoliated mountain birch roots harbored distinct fungal communities, which correlated with increasing soil nutrients and decreasing amount of host trees with green foliar mass. Ectomycorrhizal fungi (EMF) abundance and richness declined by 70–80 % with increasing defoliation intensity, while saprotrophic and endophytic fungi seemed to benefit from defoliation. Moth herbivory also reduced dominance of Basidiomycota in the roots due to loss of basidiomycete EMF and increases in functionally unknown Ascomycota. Our results demonstrate the top-down control of belowground fungal communities by aboveground herbivory and suggest a marked reduction in the carbon flow from plants to soil fungi following defoliation. These results are among the first to provide evidence on cascading effects of natural herbivory on tree root-associated fungi at an ecosystem scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bale JS, Masters GJ, Hodkinson ID et al (2002) Herbivory in global change research: direct effects of rising temperatures on insect herbivores. Glob Chang Biol 8:1–16

Kurz WA, Dymond CC, Stinson G et al (2008) Mountain pine beetle and forest carbon feedback to climate change. Nature 452:987–990

Marini L, Ayres MP, Battisti A, Faccoli M (2012) Climate affects severity and altitudinal distribution of outbreaks in an eruptive bark beetle. Clim Chang 115:327–341

Jepsen JU, Hagen SB, Ims RA, Yoccoz NG (2008) Climate change and outbreaks of the geometrids Operophtera brumata and Epirrita autumnata in subarctic birch forest: evidence of a recent outbreak range expansion. J Anim Ecol 77:257–264

Lindahl BO, Taylor AFS, Finlay RD (2002) Defining nutritional constraints on carbon cycling in boreal forests—towards a less ‘phytocentric’ perspective. Plant Soil 242:123–135

Read DJ, Perez-Moreno J (2003) Mycorrhizas and nutrient cycling in ecosystems—a journey towards relevance. New Phytol 157:475–492

Hobbie JE, Hobbie EA (2006) 15 N in symbiotic fungi and plants estimates nitrogen and farbon flux rates in Arctic tundra. Ecology 87:816–822

Treseder KK, Torn MS, Masiello CA (2006) An ecosystem-scale radiocarbon tracer to test use of litter carbon by ectomycorrhizal fungi. Soil Biol Biochem 38:1077–1082

Rineau F, Shah F, Smits MM et al (2013) Carbon availability triggers the decomposition of plant litter and assimilation of nitrogen by an ectomycorrhizal fungus. ISME J 7:2010–2022

Högberg P, Högberg MN, Göttlicher SG et al (2008) High temporal resolution tracing of photosynthate carbon from the tree canopy to forest soil microorganisms. New Phytol 177:220–228

Högberg P, Nordgren A, Buchmann N et al (2001) Large-scale forest girdling shows that current photosynthesis drives soil respiration. Nature 411:789–792

Clemmensen KE, Bahr A, Ovaskainen O et al (2013) Roots and associated fungi drive long-term carbon sequestration in boreal forest. Science 339:1615–1618

Kuikka K, Härmä E, Markkola AM et al (2003) Severe defoliation of Scots pine reduces reproductive investment of ectomycorrhizal symbionts. Ecology 84:2051–2061

Treu R, Karst JD, Randall M et al (2014) Decline of ectomycorrhizal fungi following a mountain pine beetle epidemic. Ecology 95:1096–1103

Markkola AM, Kuikka K, Rautio P et al (2004) Defoliation increases carbon limitation in ectomycorrhizal symbiosis of Betula pubescens. Oecologia 140:234–240

Gehring CA, Whitham TG (1991) Herbivore-driven mycorrhizal mutualism in insect-susceptible pinyon pine. Nature 353:556–557

Del Vecchio TA, Gehring CA, Cobb NS, Whitham TG (1993) Negative effects of scale insect herbivory on the ectomycorrhizae of juvenile pinyon pine. Ecology 74:2297–2302

Gehring CA, Cobb NS, Whitham TG (1997) Three-way interactions among ectomycorrhizal mutualists, scale insects, and resistant and susceptible pinyon pines. Am Nat 149:824–841

Cullings KW, Vogler DR, Parker VT, Makhija S (2001) Defoliation effects on the ectomycorrhizal community of a mixed Pinus contorta/ Picea engelmannii stand in Yellowstone Park. Oecologia 127:553–539

Saravesi K, Markkola A, Rautio P et al (2008) Defoliation causes parallel temporal responses in a host tree and its fungal symbionts. Oecologia 156:117–123

Saikkonen K, Ahonen-Jonnarth U, Markkola AM et al (1999) Defoliation and mycorrhizal symbiosis: a functional balance between carbon sources and belowground sinks. Ecol Lett 2:19–26

Pestaña M, Santolamazza-Carbone S (2010) Defoliation negatively affects plant growth and the ectomycorrhizal community of Pinus pinaster in Spain. Oecologia 165:723–733

Štursová M, Šnajdr J, Cajthaml T et al (2014) When the forest dies: the response of forest soil fungi to a bark beetle-induced tree dieback. ISME J 8:1920–1931

Ruohomäki K, Tanhuanpää M, Ayres MP et al (2000) Causes of cyclicity of Epirrita autumnata (Lepidoptera, Geometridae): grandiose theory and tedious practice. Popul Ecol 42:211–223

Tenow O, Nilssen AC, Bylund H et al (2013) Geometrid outbreak waves travel across Europe. J Animal Ecol 82:84–95

Jepsen JU, Hagen SB, Karlsen SR, Ims RA (2009) Phase-dependent outbreak dynamics of geometrid moth linked to host plant phenology. Proc Royal Soc B Biol Sci 276:4119–4128

Heliasz M, Johansson T, Lindroth A, Mölder M, Mastepanov M, Friborg T et al (2011) Quantification of C uptake in subarctic birch forest after setback by an extreme insect outbreak. Geophys Res Lett 38, L01704

Kaukonen M, Ruotsalainen AL, Wäli P et al (2013) Moth herbivory enhances resource turnover in subarctic mountain birch forests? Ecology 94:267–272

Tammaru T, Kaitaniemi P, Ruohomäki K (1995) Oviposition choices of Epirrita autumnata (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in relation to its eruptive population dynamics. Oikos 74:269–304

Jepsen JU, Biuw M, Ims RA et al (2013) Ecosystem impacts of a range expanding forest defoliator at the forest-tundra ecotone. Ecosystems 13:561–575

Stark S, Eskelinen A, Männistö MK (2011) Regulation of microbial community composition and activity by soil nutrient availability, soil pH, and herbivory in the tundra. Ecosystems 15:18–33

Tenow O, Bylund H (2000) Recovery of a Betula pubescens forest in northern Sweden after severe defoliation by Epirrita autumnata. J Veg Sci 11:855–862

Karlsson PS, Tenow O, Bylund H et al (2004) Determinants of mountain birch growth in situ: effects of temperature and herbivory. Ecography 27:659–667

Makkonen K, Helmisaari H-S (1998) Seasonal and yearly variation of fine-root biomass and necromass in a Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) stand. For Ecol Manage 102:283–290

Rinnan R, Michelsen A, Jonasson S (2008) Effects of litter addition and warming on soil carbon, nutrient pools and microbial communities in a subarctic heath ecosystem. Appli Soil Ecol 39:271–281

Martin KJ, Rygiewicz PT (2005) Fungal-specific PCR primers developed for analysis of the ITS region of environmental DNA extracts. BMC Microbiol 5:28

White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor JW (1990) Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ (eds) PCR Protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic, New York, pp 315–322

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T et al (2009) Introducing mothur: open source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Env Microbiol 75:7537–7541

Quince C, Lanzen A, Curtis TP et al (2009) Accurate determination of microbial diversity from 454 pyrosequencing data. Nat Meth 6:639–641

Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC et al (2011) UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27:2194–2200

Abarenkov K, Tedersoo L, Nilsson RH et al (2010) PlutoF-a web based workbench for ecological and taxonomic research, with an online implementation for fungal ITS sequences. Evol Bioinformatics 6:189–196

Tedersoo L, Nilsson RH, Abarenkov K et al (2010) 454 Pyrosequencing and Sanger sequencing of tropical mycorrhizal fungi provide similar results but reveal substantial methodological biases. New Phytol 188:291–301

Kõljalg U, Nilsson RH, Abarenkov K et al (2013) Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Mol Ecol 22:5271–5277

Smith SE, Read DJ (2008) Mycorrhizal symbiosis. Elsevier, London

Tedersoo L, May TW, Smith ME (2010) Ectomycorrhizal lifestyle in fungi: global diversity, distribution, and evolution of phylogenetic lineages. Mycorrhiza 20:217–263

Moore D, Robson GD, Trinci APJ (2011) 21st Century guide to fungi. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Gihring TM, Green SJ, Schadt CW (2012) Massively parallel rRNA gene sequencing exacerbates the potential for biased community diversity comparisons due to variable library sizes. Env Microbiol 14:285–290

Bray JR, Curtis TJ (1957) An ordination of upland forest communities of Southern Wisconsin. Ecol Monograph 27:325–349

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O'Hara RB, et al (2013) Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.0-10. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan

De Cáceres M, Legendre P (2009) Associations between species and groups of sites: indices and statistical inference. Ecology 90:3566–3574

Lindahl BD, de Boer W, Finlay RD (2010) Disruption of root carbon transport into forest humus stimulates fungal opportunists at the expense of mycorrhizal fungi. ISME J 4:872–881

Yarwood SA, Myrold DD, Högberg MN (2009) Termination of belowground C allocation by trees alters soil fungal and bacterial communities in a boreal forest. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 70:151–162

Högberg MN, Briones MJI, Keel SG et al (2010) Quantification of effects of season and nitrogen supply on tree below-ground carbon transfer to ectomycorrhizal fungi and other soil organisms in a boreal pine forest. New Phytol 187:485–493

Pena R, Offermann C, Simon J et al (2010) Girdling affects ectomycorrhizal diversity and reveals functional differences of EM community composition in a mature beech forest (Fagus sylvatica). Appl Env Microbiol 76:1831–1841

Agerer R (2001) Exploration types of ectomycorrhizae—a proposal to classify ectomycorrhizal mycelial systems according to their patterns of differentiation and putative ecological importance. Mycorrhiza 11:107–114

Druebert C, Lang C, Valtanen K, Polle A (2009) Beech carbon productivity as driver of ectomycorrhizal abundance and diversity. Plant, Cell Environ 32:992–1003

Kalliokoski T, Nygren P, Sievänen R (2008) Coarse root architecture of three boreal tree species growing in mixed stands. Silva Fennica 42:189–210

Hagerman SM, Jones MD, Bradfield GE et al (1999) Effects of clear-cut logging on the diversity and persistence of ectomycorrhizae at a subalpine forest. Can J For Res 29:124–134

Menkis A, Allmer J, Vasiliauskas R (2004) Ecology and molecular characterization of dark septate fungi from roots, living stems, coarse and fine woody debris. Mycol Res 108:965–973

Saravesi K, Ruotsalainen A-L, Cahill JF (2014) Contrasting impacts of defoliation on root colonization by arbuscular mycorrhizal and dark septate endophytic fungi of Medicago sativa. Mycorrhiza 24:239–245

Lindahl B, Stenlid J, Olsson S, Finlay R (1999) Translocation of 32P between interacting mycelia of a wood decomposing fungus and ectomycorrhizal fungi in microcosm systems. New Phytol 144:183–193

Drigo B, Anderson IC, Kannangara GSK et al (2012) Rapid incorporation of carbon from ectomycorrhizal mycelial necromass into soil fungal communities. Soil Biol Biochem 49:4–10

Nilsson LO, Wallander H (2003) Production of external mycelium by ectomycorrhizal fungi in a Norway spruce forest was reduced in response to nitrogen fertilization. New Phytol 158:409–416

Tarvainen O, Markkola AM, Ohtonen R (2003) Diversity of macrofungi and plants in Scots pine forests along an urban pollution gradient. Basic Appl Ecol 4:547–556

Boberg J, Finlay RD, Stenlid J et al (2008) Glucose and ammonium additions affect needle decomposition and carbon allocation by the litter degrading fungus Mycena epipterygia. Soil Biol Biochem 40:995–999

Allison SD, LeBauer DS, Ofrecio MR et al (2009) Low levels of nitrogen addition stimulate decomposition by boreal forest fungi. Soil Biol Biochem 41:293–302

Buée M, Reich M, Murat C et al (2009) 454 Pyrosequencing analyses of forest soils reveal an unexpectedly high fungal diversity. New Phytol 184:449–456

McMurdie PJ, Holmes S (2014) Waste not, want not: why rarefying microbiome data is inadmissible. PLoS Comput Biol 10(4):e1003531

De Carcer DA, Denman SE, McSweeney C, Morrison M (2011) Evaluation of subsampling-based normalization strategies for tagged high-throughput sequencing data sets from gut microbiomes. Appl Env Microbiol 77:8795

Wardle DA, Bardgett RD, Klironomos JN et al (2004) Ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota. Science 304:1629–1633

Teste FP, Simard SW, Durall DM et al (2009) Access to mycorrhizal networks and roots of trees: importance for seedling survival and resource transfer. Ecology 90:2808–2822

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the staff of the Lapland Research Station Kevo for assistance in the field work. BSc Taina Romppanen is acknowledged for conducting the DNA extractions. The study was conducted as a part of the Nordic Centre of Excellence Tundra, and was financed by the Academy of Finland, projects no. 133889 (KS) and no. 138309 (AMM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saravesi, K., Aikio, S., Wäli, P.R. et al. Moth Outbreaks Alter Root-Associated Fungal Communities in Subarctic Mountain Birch Forests. Microb Ecol 69, 788–797 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-015-0577-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-015-0577-8