Abstract

Purpose

Previous research on associations between screen media use and mental health produced mixed findings, possibly because studies have not examined screen activities separately or accounted for gender differences. We sought to examine associations between different types of screen activities (social media, internet, gaming, and TV) and mental health indicators separately for boys and girls.

Methods

We drew from a nationally representative sample of 13–15-year-old adolescents in the UK (n = 11,427) asking about hours per day spent on specific screen media activities and four mental health indicators: self-harm behavior, depressive symptoms, life satisfaction, and self-esteem.

Results

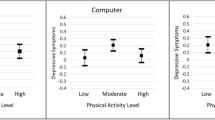

Hours spent on social media and Internet use were more strongly associated with self-harm behaviors, depressive symptoms, low life satisfaction, and low self-esteem than hours spent on electronic gaming and TV watching. Girls generally demonstrated stronger associations between screen media time and mental health indicators than boys (e.g., heavy Internet users were 166% more likely to have clinically relevant levels of depressive symptoms than low users among girls, compared to 75% more likely among boys).

Conclusion

Thus, not all screen time is created equal; social media and Internet use among adolescent girls are the most strongly associated with compromised mental health. Future research should examine different screen media activities and boys and girls separately where possible. Practitioners should be aware that some types of screen time are more likely to be linked to mental health issues than others.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alkis Y, Kadirhan Z, Sat M (2017) Development and validation of social anxiety scale for social media users. Comput Hum Behav 72:296–303

American Heart Association (2018). Limit screen time among kids, experts caution. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2018/08/06/limit-screen-time-among-kids-experts-caution. Accessed 28 July 2020

Anderson M, Jiang J (2018) Teens, social media, and technology. Pew research center. https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/. Accessed 28 July 2020

Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A (1995) Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. Intern J Method Psychiatr Rese 5:237–249

Antaramian SP, Huebner ES, Hills KJ, Valois RF (2010) A dual-factor model of mental health: toward a more comprehensive understanding of youth functioning. Am J Orthopsychiatr 80:462–472

Babic MJ, Smith JJ, Morgan PJ, Eather N, Plotnikoff RC, Lubans DR (2017) Longitudinal associations between changes in screen-time and mental health outcomes in adolescents. Mental Health Phys Act 12:124–131

Bandura A, Walters RH (1977) Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall, New York

Barryman C, Ferguson CJ, Negy C (2017) Social media use and mental health among young adults. Psy Q 89:307–314

Benenson JF, Christakos A (2003) The greater fragility of females’ versus males’ closest same-sex friendships. Child Dev 74:1123–1129

Boers E, Afzali MH, Newton N (2019) Association of screen time and depression in adolescence. JAMA Pediatr 173:853–859

Card NA, Stucky BD, Sawalani GM, Little TD (2008) Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Dev 79:1185–1229

Centre for Longitudinal Studies (2018) The Millennium Cohort Study. https://cls.ucl.ac.uk/cls-studies/millennium-cohort-study/

Christakis D (2019) The challenges of defining and studying “digital addiction” in children. JAMA 1:2

Council on Communications and Media (2013) Children, adolescents, and the media. Pediatrics 132:958–961

de Vries DA, Peter J, de Graaf H, Nikken P (2016) Adolescents’ social network site use, peer appearance-related feedback, and body dissatisfaction: testing a mediation model. J Youth Adolesc 45:211–224

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S (1985) The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J Pers Assess 49:71–75

Dwyer R, Kushlev K, Dunn E (2018) Smartphone use undermines enjoyment of face-to-face social interactions. J Exp Soc Psychol 78:233–239

Falbe J, Davison KK, Franckle RL, Ganter C, Gortmaker SL, Smith L, Taveras EM (2015) Sleep duration, restfulness, and screens in the sleep environment. Pediatrics 135:e367–375

Ferguson CJ (2017) Everything in moderation: moderate use of screens unassociated with child behavior problems. Psychiatr Q 88:797–805

Fink E, Patalay P, Sharpe H, Holley S, Deighton J, Wolpert M (2015) Mental health difficulties in early adolescence: a comparison of two cross-sectional studies in England from 2009 to 2014. J Adolesc Health 56:502–207

Flook L (2011) Gender differences in adolescents’ daily interpersonal events and well-being. Child Dev 82:454–461

Hoyt LT, Chase-Lansdale L, McDade TW, Adam EK (2012) Positive youth, healthy adults: Does positive well-being in adolescence predict better perceived health and fewer risky health behaviors in young adulthood? J Adolesc Health 50:66–73

Hrafnkelsdottir SM, Brychta RJ, Rognvaldsdottir V, Gestsdottir S, Chen KY, Johannsson E, Arngrimsson SA (2018) Less screen time and more frequent vigorous physical activity is associated with lower risk of reporting negative mental health symptoms among Icelandic adolescents. PLoS ONE 13(4):e0196286

Hunt MG, Marx R, Lipson C, Young J (2018) No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression. J Soc Clin Psychol 37:751–768

Jelenchick LA, Eickhoff JC, Moreno MA (2013) “Facebook depression?” Social networking site use and depression in older adolescents. J Adolesc Health 52:128–130

Kelly Y, Zilanawala A, Booker C, Sacker A (2019) Social media use and adolescent mental health: findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. EClin Med 4:8

Keyes KM, Gary D, O’Malley PM, Hamilton A, Schulenberg J (2019) Recent increases in depressive symptoms among US adolescents: trends from 1991 to 2018. Social Psyc Psychiatr Epidemiol 7:3

Kushlev K, Hunter JF, Proulx J, Pressman SD, Dunn E (2019) Smartphones reduce smiles between strangers. Comput Hum Behav 91:12–16

LaFontana KM, Cillessen AHN (2010) Developmental changes in the priority of perceived status in childhood and adolescence. Soc Dev 19:130–147

Lin L, Sidani JE, Shensa A, Radovic A, Miller E, Colditz JB, Primack BA (2016) Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults. Depress An 33:323–331

Lobel A, Engels RE, Stone LL, Burk WJ, Granic I (2017) Video gaming and children’s psychosocial wellbeing: a longitudinal study. J Youth Adolesc 46:884–897

Luby J, Kurtz S (2019) Increasing suicide rates in early adolescent girls in the United States and the equalization of sex disparity in suicide: The need to investigate the role of social media. JAMA Open 40:35–13

McFarland LA, Ployhart RE (2015) Social media: a contextual framework to guide research and practice. J Appl Psychol 100:1653–1677

McKnight CG, Huebner ES, Suldo S (2002) Relationships among stressful life events, temperament, problem behavior, and global life satisfaction in adolescents. Psychol Sch 39:677–687

Mercado MC, Holland K, Leemis RW (2017) Trends in emergency department visits for nonfatal self-inflicted injuries among youth aged 10 to 24 years in the United States, 2001–2015. J Am Med Assoc 318:1931–1933

Moreira PAS, Cloninger CR, Dinis L, Sa L, Oliveira JT, Dias A, Oliveira J (2014) Personality and well-being in adolescents. Front Psychol 5:1494

Morgan C, Webb RT, Carr MJ, Kontopantelis E, Green J, Chew-Graham CA, Kapur N, Ashcroft DM (2017) Incidence, clinical management, and mortality risk following self harm among children and adolescents: cohort study in primary care. BMJ 359:j4351

Nesi J, Prinstein MJ (2015) Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking: Gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Child Psychol 43:1427–1438

NHS (2018). Mental health of children and young people. London: National Health Service. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2017/2017. Accessed 28 July 2020

Orben A, Przybylski AK (2019) The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nat Hum Behav 37:92–34

Orben A, Przybylski AK (2019) Screens, teens, and psychological well-being: Evidence from three time-use-diary studies. Psychol Sci 20:92–75

Ostrov JM, Gentile DA, Crick NR (2006) Media exposure, aggression and prosocial behavior during early childhood: a longitudinal study. Soc Dev 15:612–627

Pappa E, Apergi F-S, Ventouratau R, Janikian M, Beratis IN (2016) Online gaming behavior and psychological well-being in Greek adolescents. Eur J Soc Behav Sci 60:1988–1998

Patalay P, Gage SH (2019) Changes in millennial adolescent mental health and health-related behaviours over 10 years: a population cohort comparison study. Intern J Epidemiol 3:123–854

Przybylski AK (2014) Electronic gaming and psychosocial adjustment. Pediatrics 134:e716–e722

Przybylski AK, Weinstein N (2017) A large-scale test of the Goldilocks hypothesis: quantifying the relations between digital-screen use and the mental well-being of adolescents. Psychol Sci 28:204–215

Riehm KE, Feder KA, Tormohlen KN, Crum RM, Young AS, Green KM, Pacek LR, LaFlair LN, Mojtabai R (2019) Associations between time spent using social media and internalizing and externalizing problems among US youth. JAMA Psychiatry 53:73–84

Romer D, Bagdasarov Z, More E (2013) Older versus newer media and the well-being of United States youth: Results from a national longitudinal panel. J Adolesc Health 52:613–619

Rose AJ (2002) Co-rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Dev 73:1830–1843

Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Lewis RF (2015) Frequent use of social networking sites is associated with poor psychological functioning among children and adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Net 18:380–385

Schalet BD, Cook KF, Choi SW, Cella D (2014) Establishing a common metric for self-reported anxiety: Linking the MASQ, PANAS, and GAD-7 to PROMIS anxiety. J Anxiety Disord 28:88–96

Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW (2009) Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 20:488–495

Shakya HB, Christakis NA (2017) Association of Facebook use with compromised well-being: a longitudinal study. Am J Epidemiol 185:203–211

Shih JH, Eberhart NK, Hammen CL, Brennan PA (2006) Differential exposure and reactivity to interpersonal stress predict sex differences in adolescent depression. J Clin Child Adoles Psychol 35:103–115

Slater MD (2015) Reinforcing spirals model: conceptualizing the relationship between media content exposure and the development and maintenance of attitudes. Med Psychol 18:370–395

Spiller HA, Ackerman JP, Spiller NE, Casavant MJ (2019) Sex- and age-specific increases in suicide attempts by self-poisoning in the United States among youth and young adults from 2000 to 2018. J Pediat 46:93–126

Steers MN, Wickham RE, Acitelli LK (2014) Seeing everyone else’s highlight reels: how facebook usage is linked to depressive symptoms. J Soc Clin Psychol 33:701–731

Sterling G. (2016). Nearly 80 percent of social media time now spent on mobile devices. Marking Land. https://marketingland.com/facebook-usage-accounts-1-5-minutes-spent-mobile-171561. Accessed 28 July 2020

Thabrew H, Stasiak K, Bavin LM, Frampton C, Merry S (2018) Validation of the mood and feelings questionnaire (MFQ) and short mood and feelings questionnaire (SMFQ) in New Zealand help-seeking adolescents. Intern J Method Psychiatr Res 75:94–116

Tromholt M (2016) The Facebook experiment: Quitting Facebook leads to higher levels of well-being. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Net 19:661–666

Tiggemann M, Slater A (2017) Facebook and body image concern in adolescent girls: a prospective study. Int J Eat Disord 50:80–83

Twenge JM (2020) Why increases in adolescent depression may be linked to the technological environment. Curr Opin Psychol 32:89–94

Twenge JM, Campbell WK (2018) Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Prev Med Rep 12:271–283

Twenge JM, Campbell WK (2019) Digital media use is linked to lower psychological well-being: Evidence from three datasets. Psychiatr Q 12:7

Twenge JM, Joiner TE, Rogers ML, Martin GN (2018) Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clin Psychological Sci 6:3–17

Twenge JM, Martin GN, Campbell WK (2018) Decreases in psychological well-being among American adolescents after 2012 and links to screen time during the rise of smartphone technology. Emotion 18:765–780

Twenge JM, Martin GN, Spitzberg BH (2019) Trends in US adolescents’ media use, 1976–2016: The rise of digital media, the decline of TV, and the (near) demise of print. Psychol Med Cult 43:94

Verduyn P, Lee DS, Park J, Shablack H, Orvell A, Bayer J, Kross E (2015) Passive Facebook usage undermines affective well-being: experimental and longitudinal evidence. J Exp Psychol Gen 144:480–488

Viner RM, Aswathikutty-Gireesh A, Stiglic N, Hudson LD, Goddings A-L, Ward JL, Nicholls DE (2019) Roles of cyberbullying, sleep, and physical activity in mediating the effects of social media use on mental health and wellbeing among young people in England: a secondary analysis of longitudinal data. Lancet Child Adolest Health 4:9

Wang JL, Manuel D, Williams J, Schmitz N, Gilmour H, Patten S, Birney A (2013) Development and validation of prediction algorithms for major depressive episode in the general population. J Affect Disord 151:39–45

Watkins D, Cheng C, Mpofu E, Olowu S, Singh-Sengupta S, Regmi M (2003) Gender differences in self-construal: how generalizable are Western findings? J Soc Psychol 143:501–519

Wiederhold BK (2018) All the world’s a stage (including social media). Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Network 21:591–592

Yau JC, Reich SM (2018) “It’s just a lot of work”: adolescents’ self-presentation norms and practices on Facebook and Instagram. J Res Adoles 5:94–97

Yuen EK, Koterba EA, Stasio MJ, Patrick RB, Gangi C, Ash P, Barakat K, Greene V, Hamilton W, Mansour B (2019) The effects of Facebook on mood in emerging adults. Psychol Med Cult 3:9

Zhang F, Kaufman D (2017) Massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) and socio-emotional wellbeing. Comput Hum Behav 73:451–458

Funding

This research received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

J.M.T. has received speaking honoraria and consulting fees for presenting research and is the author of several books, most recently iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood. E. F. declares no conflicts of interest.

Availability of data and material

Data and materials are available at https://beta.ukdataservice.ac.uk/datacatalogue/series/series?id=2000031.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Twenge, J.M., Farley, E. Not all screen time is created equal: associations with mental health vary by activity and gender. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 56, 207–217 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01906-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01906-9