Abstract

This paper analyzes the geometry and proportions of the funeral chapel of Sarenput II, built some 4,000 years ago in the necropolis of Qubbet el-Hawa in Egypt. The analysis is done with the utmost respect for ancient sources, and in particular for Egyptian mathematical knowledge. In a first general analysis, the different parts that make up the chapel are analysed in terms of both volume and surface. Later, the most representative elements, the hypostyle hall and sanctuary are studied in greater detail. Here, we encounter geometric shapes that are very close to the ratios √2, 2/√3 and √2/√3, which are derived from simple geometric shapes such as squares, rectangles √2 and equilateral triangles. Ancient Egyptians could achieve their approximations by unit fractions in accordance with the Egyptian system of numerical notation. Finally, with the data obtained, the study proposes a hypothesis about the possible design method of the funeral chapel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The archaeological site of Qubbet El-Hawa is located on a rocky outcrop on the western bank of the Nile, opposite the modern city of Aswan. Between the two banks lies Elephantine Island, the largest island south of the First Cataract, which was the capital of the first district of Upper Egypt, that is, the southernmost province of ancient Egypt. About a hundred hypogea [Edel 2008] have been found in Qubbet el-Hawa. These are rock-hewn tombs which belonged to the governors and higher officials of Elephantine during the Old Kingdom and the Middle Kingdom. Although most of the tombs were built from the Sixth Dynasty on, in the Old Kingdom [Jiménez Serrano 2013: 30], it was during the Twelth Dynasty, in the Middle Kingdom, that they reached their moment of maximum splendour [Jiménez Serrano 2013].

Although no tombs have been discovered dating from the First Intermediate PeriodFootnote 1 and the Twelfth Dynasty in Qubbet el-Hawa, it seems clear that when Sarenput I came to power in the province, during the reign of Senwosret I (1920-1875+6),Footnote 2 there was a change in the architectural design of the tombs and their finishings. Sarenput declares in his biography: “I appointed craftsmen to work in my tomb” [Gardiner 1908: 125, Taf. VI, line 8; Sethe 1935: 2 §14]. In the first half of the Twelfth Dynasty, over a period of about 100 years, from the reign of Senwosret I (1920–1875+6) until the early years of the reign of Senwosret III (1837–1819), the governors of Elephantine built a series of tombs (QH36, QH32 and QH31) that have many architectural features in common. Among them we can highlight the tomb QH31 of Sarenput II, grandson of Sarenput I [Müller 1940: 96–99, 104–105].

Sarenput II was most probably born during the reign of Amenemhet II (1878–1843+3), and his career in government spanned the next two reigns: Senwosret II and Senwosret III [Habachi 1985: 40–48]. Like his grandfather, Sarenput I accumulated various administrative, religious and military titles, so we can consider him one of the most important individuals of his time [Habachi 1985: 40–48].Footnote 3 His tomb, reflecting the social status and power of its owner, is a magnificent example of an architecture which achieved perfect harmony between the unique work of the individual architect and the development of the traditions of local Aswan art and architecture [Müller 1940: 99–103].

This paper analyses the geometry and proportions of the funeral chapel of Sarenput II but we do so with the utmost respect for ancient sources, in particular for Egyptian mathematical knowledge. In contrast, to date, most studies that have been carried out to explain the design and proportions of ancient monuments deriving from geometric figures, however complex they may be, have ended up straying far from the facts of historical and archaeological evidence [Rossi and Tout 2002: 101–102]. For example, when looking at other, very complicated studies that have been conducted so far, we can highlight Badawy’s theory which, after analysing more than fifty buildings, concludes that the golden section, and its relationship with the Fibonacci sequence, is the basis of the theory about proportions in ancient Egyptian architecture [Badawy 1966: 183–185]. However, the Fibonacci sequence and the golden section have little in common with the ancient Egyptian mathematical documents that survive and are far removed from the mentality of the ancient Egyptians [Rossi and Tout 2002: 101–102].

Therefore, to be as rigorous as possible, the methodology used in this paper can be summarized in the following scheme: general description of the funerary complex and its main parts; the provision of precise measurements in units of the Egyptian system of measurement, the use of the ancient sources, particularly the study of Egyptian mathematical knowledge, and the location of geometric shapes and the simple relationships between them.

Description the funerary chapel

The interior of the funerary complex of Sarenput II consists of two distinct areas: the funeral chapel, which was accessible and is made up of various rooms, and the burial area, which is inaccessible and is made up of different shafts and burial chambers (Fig. 1).

The interior of the tomb of Sarenput II consists of a succession of spaces arranged along the longitudinal axis, propitiating and directing movement towards a single focus: the sanctuary, buried 30 m down into the rock of the hill. A long processional path for the burial of the deceased leads from the hypostyle hall, traversing a vaulted corridor, to the cult chamber, which is placed in the deepest part of the tomb and was the place where offerings were made to the deceased [Müller 1940: 96–99].

From the entrance, and in the direction of the cult chamber, the ceiling height decreases progressively in each unit while the ground level increases. This situates the chapel of offerings as the key point of the funeral complex [Badawy 1966: 163–168; Arnold 2003: 22–23].

All architectural and decorative elements––the three pairs of strong pillars that support the roof of the hypostyle hall, the three pairs of statues of Osiride [Müller 1940: 72–74] in the hall, and the two pairs of pillars of the chamber of offerings––are arranged symmetrically about the longitudinal axis.

The funeral chapel is divided into three clearly different areas:

-

1.

The exterior, unfinished courtyard.Footnote 4

-

2.

The hypostyle hall [Budge 1888: 25–30; De Morgan 1894: 153–155; Müller 1940: 62–64], the reception area for the ceremonial funeral cortege. This is architecturally designed for the living, on a monumental scale in order to convey the greatness of the owner. This explains the elaborate design, the higher ceiling level, the level floor and the carefully polished walls.

-

3.

The cult chamber [Budge 1888: 25–30; De Morgan 1894: 153–155; Müller 1940: 64–65], dug deep into the complex. This was where funeral rites were performed. This was accessible only to the priests and the closest relatives. The floors, parallel to the ceilings, slope slightly following the direction of the rock stratum.

This present paper focusses mainly on the most important elements of the funeral complex: the hypostyle hall, which is architecturally the most significant space, and the sanctuary, the most sacred place.

The hypostyle hall

The pillared hall is noteworthy for its solid geometric forms, with its powerful grained sandstone pillars carved directly into the rock [Budge 1888: 25–30; De Morgan 1894: 153–155; Müller 1940: 66–69]. Although it is lacking a mural decoration, the alternating horizontal stripes with the warm tones of the sandstone are impressive [Müller 1940: 62]. The roof of the hall is supported by two rows of three square pillars arranged equidistant from each other and with the walls of the room, in both directions, which rest on a flat and wide base, slightly raised from the ground. Two architraves transmit the weight of the roof to the pillars, and divide the room into three high naves which are oriented in the direction of the longitudinal axis of the tomb. The central nave is framed by the powerful pillars and serves as a path to the rear of the funeral chapel. The pillars are stylized upwards because their faces oriented toward the main shaft and the sanctuary are slightly sloped, which makes the central nave gain considerably in spaciousness. All this arrangement is consequent with the idea of path and highlights the direction to the sanctuary located in the depths of the tomb. The door that leads to the corridor [Müller 1940: 96–99] clearly separates the two main spaces, the reception area and the area of cult and represents the threshold that protects the inner sacred areas. To cross it, you must first go up nine steps that are cut into the rock. Also, it is centered on the western wall of the room, equidistant from the floor and ceiling of the room and, quite possibly, its dimensions were calculated so that the sanctuary could be lit and seen from the entrance of the tomb [Müller 1940: 96–99].

The sanctuary

The sanctuary stands on a pedestal and at one time had a double door that opened to the entrance of the tomb [Müller 1940: 64–67]. This architectural element is enhanced with an outer frame consisting of two traditional elements: the torus moulding, which runs along three sides, and a cavetto cornice [Schulz and Seidel 2005: 583]. This is the only place in the funeral complex of Sarenput II which was fully decorated [Müller 1940: 74–80]. This was probably due to fact that the artists centered their work on the most sacred area of the tomb after the sudden death of his owner during the last stages of construction [Müller 1940: 70]. For the Egyptians, this place represented the threshold between the worlds of the living and the dead, and through it the spirit of the deceased could enter or leave the tomb to receive the offerings presented to him [Wilkinson 2000: 70–71]. The decoration inside represents one of the finest examples of painting from the Middle Kingdom. We can highlight its careful detail and vivid colours, which have survived almost intact [Müller 1940: 68–69, 74–80]. The main scene depicts Sarenput II, sitting on the throne at the table of offering, with his son Ankhu who present him a lotus flower [Budge 1888: 25–30; Müller 1940: 96–99] (see Fig. 8, left). On the southern wall (see Fig. 8, right) Sarenput II appears standing with a cane and sekhem scepter, a symbol of power. His son appears behind in an attitude of devotion, with his right hand on his own left shoulder and left arm slightly extended forward, and before them is the wife of Sarenput and mother of Ankhu.

Development of the planimetry of the funeral chapel of Sarenput II

The first thing that is required to make a serious study of the proportions of any ancient monument is to have a detailed survey, with the necessary plans and sections for its complete definition.

To draw up a plan for the funeral chapel of Sarenput II,Footnote 5 the data obtained first-hand with the help of laser level served as a basis. The laser level was placed on the axis of the tomb to calculate the inclinations of floors and ceilings of the different areas,Footnote 6 and many photographs were taken, especially, during the 2008–2009 excavation campaign of the Qubbet el-Hawa Project.Footnote 7 In addition, all data was checked and/or corrected by the architects of the Qubbet el-Hawa project during the sixth season of excavation in March of 2014.Footnote 8 Further, data was taken from other tombs of the Middle Kingdom and, in a preliminary analysis, appears to support the conclusions of this paper. The summary of the measurement data is given in Table 1. The general planimetry of the funeral chapel of Sarenput II is shown in Fig. 1.

Method of constructing a rock tomb

However, before studying of the proportions of the funeral chapel of Sarenput II, it is important to understand the construction system used by the ancient Egyptians.

The excavation works began, as is the case in quarries, by choosing the level of the ceiling height to dig a narrow preliminary tunnel which runs to the end of the tomb. On the main axis, on the roof of this tunnel, the position of the pillars and the transverse walls were scored [Arnold 1991: 213]. Once they had established the depth to which the various interior spaces were to reach, they continued digging to each side, right and left. They kept the pillars connected to the side wall of the room until a later stage of the work. Next, they retreated backwards in the direction of the entrance to complete the planned layout of the tomb [Arnold 1991: 203–204]. In the funeral chapel QH31 the floors and ceilings are parallel but slightly inclined in an east–west direction as we move into the tomb, following the rock stratum. However, in the case of the pillared hall, the builders were careful to leave the ground horizontal, so its height decreases toward the western wall. The walls of this chamber are cleanly cut but only the pillars and the western wall, which receives incident light rays through the entrance, are polished to a fine finish, with curved, soft surfaces and with sharp and clear edges [Müller 1940: 62–64]. Following on from this, for the purposes of an analysis of the proportions of the pillared hall, we have drawn up an “ideal” chamber with parallel ceilings and floors.

The ground plan of the chapel: form and function

While the hypostyle hall has a rectangular ground plan oriented towards the chamber of offerings to the deceased, the ground plan of the cult chamber, which is the place where we find the chapel with the statue of the deceased at the end of the processional path, is constructed in a shape that is approximately square.

In the ground plan of the tomb, form and function coincide. The square spaces (such as the offerings chamber) define specific points of activity, while the rectangular spaces (pillared hall) encourage movement. The square, with its four equal sides, lacks a specific direction and is by nature static. The remaining rectangles are variations of the square, a result of increasing one of its sides, and so the spaces become more dynamic [Ching 1982: 41]. However, the cult chamber is not perfectly square [Budge 1888: 4–40; Müller 1940: 64–65]. Its pillars are located symmetrically with respect to the main axis but the ground plan is shifted slightly to the north, where the entrance to the burial chamber is found. Possibly, the symmetry of the chamber was deliberately broken to give more width to the side nave, providing the area of access to the burial chamber with more space. However, it could also be because, at a greater depth, the workers would encounter worse working conditions, lack of visibility and ventilation, or defective material, which could explain why they were forced to compromise on the shape and size of the chamber [Arnold 1991: 211–218].

The funeral chapel in Egyptian units of measurement

For us to understand the mentality of the ancient Egyptians, it is important to transform the measurements from the funeral chapel (see Table 1) into units of the ancient Egyptian system of measurement (see Table 2).

In Ancient Egypt, the unit of measurement of length was the royal cubit. This is known because numerous cubit rods were found [Lepsius 1865: 14–18]. Most of them are made of hard stone and were used as votive offerings in the funeral rites. However, some of them are made of wood and were used as measurement tools by ancient architects [Arnold 1991: 251]. For example, during the excavation of the tomb of the architect Kha at Deir el-Medina, two cubits rods were found, which are now in the Egyptian Museum in Torino, Italy. One was a cubit of gilded wood, which apparently was an honorary royal gift, and the other one is a double cubit, of plain wood, that can be folded in two parts on hinges and was probably used as a working tool by the architect [Schiaparelli 1927: 168–173, Figs. 154–156 and 80]. The lengths of the cubit rods are variable [Lepsius 1865: 14–18], which reminds us that the old measurements were not as standardized as those of today, and that such differences should be taken into account in our calculations of Egyptian buildings [Arnold 1991: 251]. However, modern Egyptologists consider the length of the royal cubit to be equal to about 0.523 m [Griffith 1881-2: 403–404; Gardiner 1957: 199; Gillings 1972: 207].

Regardless of its exact length, the rods were marked in cubits, palms and fingers, as well as halves, thirds and quarters of cubit [Gillings 1972: 220; Arnold 1991: 7–10]. Each cubit can be divided into seven palms and each palm in four fingers [Lepsius 1865: 14–18; Gillings 1972: 207–208; Arnold 1991: 251]. Moreover, multiples such as khet, which measured 100 cubits, and submultiples such as remen, which measured five palms, were also used [Gillings 1972: 207–208].

Calculations in Egyptian building construction

Egyptian mathematical knowledge is revealed through remaining mathematical texts written on papyri, ostraca and leather, which mostly date from the Middle Kingdom: the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus [Peet 1923], the Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll [Glanville 1927], the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus [Struve 1930], the Reisner Papyrus [Clagett 1999: 261–296] and some fragments of the Kahun papyrus [Griffith 1897]. In most cases, it appears that these are didactic documents with simple and practical examples that were used for teaching, although some calculations show that they were able to solve much more complex problems [Clagett 1999: 262].

From the point of view of construction, there is a very interesting example of true accounting in the Reisner Papyrus, which consists of four fragments, half eaten by worms, dating from the reign of Senwosret I (Twelfth Dynasty). The fragments come from administrative records that show the practical details for carrying out the work of a temple, a monument or a tomb [Clagett 1999: 261–262]. This is a list of the results of the calculation of volumes from measurements in whole cubits, 1/2, 1/3, 1/4 or other fractions of cubit such as palms and fingers. These lists show the data of the excavation, the materials used and the workforce (in number of man-days), and other various tasks related to the transport of workers and materials, and finally, data on the cost of each of these operations [Gillings 1972: 218–221, Table 22.2; Clagett 1999: 261–262]. Accordingly, for the construction of the funerary chapel of Sarenput II, it is possible to draw up a similar list (Table 2), a result of a budget and/or a time limit for the completion of the works. The first thing that we can observe is that, in general, measurements on the main axis coincide in whole cubits.

Analysis of volumes

We also established that the hypostyle hall is the most important space in the funeral chapel, which is 4/5 = 1/2 + 1/5 + 1/10 (80 %) of the total volume excavated. The remaining 1/5 (20 %), is divided between the cult chamber and connecting spaces (entrance tunnel and corridor). Of that 1/5, 1/10 (10 %) corresponds to the cult chamber and the other remaining 1/10 is divided between the tunnel entrance and the corridor, connecting the hypostyle hall with the cult chamber, at a ratio of 1/3 and 2/3 respectively. From these data it may appear that in planning the funeral chapel, the volumes of the different parts might have been established proportionally according to their importance. In fact, examples of obtaining measurements of a container from its volume are included in the Rhind papyrus, one of the main sources of knowledge of Egyptian mathematics. This was copied by a scribe named Ahmes from earlier documents dating from the time of King Amenemhet III (Twelfth Dynasty) [Clagett 1999: 113]. For example, in problem 45, the measurements of a rectangular granary are obtained from its volume of grain of 7,500 quadruple heqat. The result is 10 × 10 × 10 cubits. Further, in problem 46, a rectangular granary with capacity for 2,500 quadruple heqat of grain is calculated, the resulting dimensions were 10 × 10 × (3 + 1/3) [Clagett 1999: 160–161].

Analysis of areas

Similarly, we have found that the ground plan of the pillared hall has an area of 375 square cubits, which is 3/4 = 1/2 +1/4 (75 %) of the total area of the funeral chapel. The remaining 1/4 (25 %) is shared between the other spaces.

In this regard, there are several examples of surface distribution that appear in the Berlin Papyrus 6619, written between the second half of the Twelfth Dynasty and the Thirteenth Dynasty [Gillings 1972: 161–162; Clagett 1999: 249]. One problem obtains two squares whose surfaces add up to 100 square cubits, with one side being 1/2 +1/4 (3/4) of the other. The result is two squares with sides of 6 and 8 cubits. A second problem divides a square of 400 square cubits into two smaller squares, whose sides are in proportion 2–1 + 1/2 (4/3, the inverse of the previous ratio). The result is two squares with sides of 16 and 12 cubits [Gillings 1972: 161–162; Clagett 1999: 250–252]. Thus, it is possible that calculations of areas and volumes, as in the above examples, could have been used in the construction of the funerary chapel of Sarenput II, as well as in other monuments of ancient Egypt [Gillings 1972: 231].

Measurements and proportions of the hypostyle hall

After reviewing the overall proportions in volumes and areas of the funeral chapel the study will focus on the hypostyle hall. Here, the cross section has dimensions of 16 cubits 2 palms wide, and 8 cubits one palm high (measured at the crest of the vault) (see Table 3).

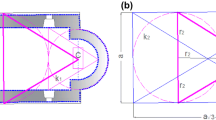

In the longitudinal direction of the hall, the pillars are arranged equidistantly from each other and with the walls, to fit the shape of the room. However, the faces oriented to the sanctuary are slightly sloped, because they were cut with an upward incline (Fig. 2).

In the transverse direction, the pillars are also arranged equidistantly from each other and with the walls, to fit the shape of the room, but the top of the nave is somewhat wider (2 palms) [Müller 1940: 62–64] than the lateral naves (Fig. 3).

This is due to the slightly sloped faces oriented to the central nave, which were cut with an upward incline too, and suggests that the adjustment could have been made to emphasize the importance of the main axis of the tomb as a place of passage in the ritual [Müller 1940: 62–64]. Whatever the reason, the western wall of the hypostyle hall is approximately in the shape of a double square rectangle, that is the ratio 1:2 (Fig. 4). This proportion is believed to have been very important in the design of the overall structure of facades and architectural elements in the architecture of ancient Egypt [Badawy 1965: 25].

Furthermore, the floor of the hypostyle hall is in a rectangular shape which almost exactly fits that of a rectangle whose proportion is given by the ratio between the diagonal and the side of a square (Fig. 5), that is, the irrational number √2 (1.4142…).

Accordingly, the ground plan of the hypostyle hall can be divided according two axes of symmetry, resulting in four new smaller √2 rectangles. Thus, the north and south walls of the room are rectangular with the proportions of a double √2 rectangle joined by its smaller side (Fig. 6).

The ratio √2 is important because it solves the problem of the duplication of a rectangle while maintaining proportions. If a square is divided into two equal rectangles, it is clear that they no longer maintain the shape of a square. This happens in any static rectangle. However, the two halves of a √2 rectangle have this same proportion.

For the funeral chapel of Sarenput II, apparently, everything appears to indicate that the hypostyle hall may have been spatially designed, as its dimensions of length, width, and height respond to the ratios √2, 1, 1/2, which are obtained from the square, half square and √2 rectangle.

Egyptian approach to √2 rectangle

Is it possible that the ancient Egyptians used the ratio √2? Is it possible that the ancient Egyptians used the ratio √2? It is traditionally accepted that the concept of incommensurability was not discovered until the fifth century B.C., many centuries after the Twelfth Dynasty.

However, in ancient Egypt “easy” relationships were possibly adopted such as approximations of a geometric method which could be used independently of arithmetical calculation [Lauer 1960: 87–88, 91–97, 258–259]. Thus, the ancient Egyptians could obtain a good approximation to the √2 rectangle by the ratio 5/7, the relationship between a remen (5 palms), and a cubit (7 palms). The diagonal of a square whose side measures a remen is approximately equal to a cubit.

However, with respect to fractional numbers, the scribes only used unit fractions, with numerator equal to 1, with the exception of 2/3, and sometimes 3/4. Percentages such as 3/5, for example, were expressed by a sum of unit fractions. However, at least from the Middle Kingdom onwards, the result was never 1/5 +1/5 +1/5, but was, for example, 1/2 +1/10 [Rossi and Tout 2002: 104]. With regard to this, during excavations in the private tomb of Senenmut (TT71), the architect who designed the temple at Deir el-Bahri for Queen Hatshepsut [Kostof 1977: 5–7; Gillings 1972: 86–88], many ostraca came to light that were studied by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and then returned to Cairo in 1954. These are administrative ostraca in which working hours and work that was carried out on a construction are recorded. In an ostracon (nº 153), 2 and 4 divided by 7 are obtained. These are expressed in unit fractions by an arithmetical calculation [Hayes 1942]. Although there is more than one combination of unit fractions that can be used to express these numbers, the standard response is recorded as:

Using the ostracon calculation method, with the sum of unit fractions in terms of palms, equal to 1/7 of cubit, the following table may be obtained [Gillings 1972: 209]:

In our case, it is possible to calculate the width of the ground plan of the hypostyle hall, following the system used by the Egyptians [Gillings 1972: 16–19] from the length of the hall (23 cubits), assuming that both sides are in proportion 5/7 (1/2 +1/7 +1/14):

1 | 23 | |

1/2 | 11 + 1/2 | |

1/7 | 3 + 1/4 + 1/28 | |

1/14 | 1 + 1/2 + 1/7 | |

Total | 1/2 + 1/7 + 1/14 | 16 + 1/4 + 1/7 + 1/28 |

(5/7) | (16 + 3/7 = 115 palms) |

A similar example of calculation of the area of a rectangle is shown in problem no. 6 of the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus [Gillings 1972: 246–248], dated slightly before the Rhind papyrus, which is now in the Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow (4576). In this problem the sides of a rectangle with an area of 12 square units are obtained, knowing that they are in proportion 1/2 +1/4 [Gillings 1972: 137–138], a proportion which, as already seen, was commonly used in the teaching examples for calculations. The scribe calculated the smaller side of a rectangle starting from a square whose side is its longer side. The solution is a rectangle with sides of 3 and 4 cubits respectively [Gillings 1972: 138; Clagett 1999: 214–215]. However, it could also be calculated assuming that the width and length of the hypostyle hall are in proportion 7/10 (1/2 +1/5):

1 | 23 | |

1/2 | 11 + 1/2 | |

1/5 | 4 + 1/2 + 1/10 | |

Total | 1/2 + 1/5 | 16 + 1/10 |

(7/10) | (16 + 1/10 ≈ 113 palms) |

A good approximation of the shape of the floor of the pillared hall is achieved, below and above, by the ratios 7/10 (0,70) and 5/7 (0,714285…), respectively.

It is possible to make a closer approximation by calculating the average of these two values, 115−113, because in fact the width of the room is 114 palms. Using unit fractions, the average of the two ratios, 5/7 and 7/10, is 1/2 + 1/10 + 1/14 + 1/28. Thus, the room has width/length dimensions, in palms, of 114/161 (0.708074…), which is a very good approximation to the value of 1/√2 (0.707106…). But it is also possible to make calculations in reverse, starting from the width of the room, to obtain a good approximation to the shape of the floor of the pillared hall, above and below, by the ratios 10/7 (1.42857…) and 7/5 (1.40), respectively.

Similarly, a closer approximation is achieved with the average of the two ratios, 10/7 and 7/5, that is, 1 + 1/5 + 1/7 + 1/14. Curiously, 161/114 can also be obtained by Egyptian mathematical calculations, for example:

In any case, the hall has length/width dimensions, in palms, of 161/114 (1.4122807…), which is a very good approximation of the value of √2 (1.4142135…).

Measurements and proportions of the sanctuary

When focusing on the study of the proportions of the sanctuary, it is apparent that its interior measures 50 fingers wide, 60 fingers deep and 70 fingers high (see Table 4). Thus, its dimensions are related to each other by the proportion 5/6/7.

As noted, a rectangle whose short and long sides are in ratio 5/7 is a good approximation of the √2 rectangle.

Similarly, a rectangle whose short and long sides are in ratio 6/7 is a good approximation to the 2/√3 rectangle, in which it is possible to inscribe an equilateral triangle with 2 unit sides. If we superimpose one equilateral triangle upon another which has a base of 7 units and a height of 6, we observe that the contours almost merge (Fig. 7) [Choisy 1899: 51–58]. It is known, through the Greek historian Plutarch [García Valdes 1996:56; Viollet Le-Duc 1877: 391–397], that the equilateral triangle, with its three equal angles and three equal sides, was regarded by the Egyptians as a perfect figure. No geometric figure provided more satisfaction to the mind, and none fulfilled better those conditions of regularity and stability that are pleasing to the eye.

Accordingly, each wall of the sanctuary responds to a different proportion, defined as the ratio of two integers that correspond to a sum of unit fractions according to the measurement system of Ancient Egypt. The front wall is in the approximate shape of a √2 rectangle and the side walls are in the approximate shape of a rectangle with the ratio 2/√3, the ratio between the base and the height of an equilateral triangle (Fig. 8).

On the other hand, when we focus only on the decorated area, we can see that the decoration takes up almost exactly a square at the top of the front wall. On the side walls, it takes up a horizontally oriented rectangle, also located on the top of the surface, -with an approximate ratio of √2/√3, which also coincides with the proportions of the roof and the floor of the sanctuary (Fig. 9).

The pyramids of Amenemhet I, II and III

At this point, the question arises as to whether there are examples of Egyptian architecture which share the proportions of Sarenput II ‘s tomb.

Unfortunately, while the Middle Kingdom experienced a boom in the construction of temples, many of them were demolished or significantly modified in order to be incorporated into later more complex buildings which were erected on the same site. The subsequent lack of remains of these buildings has made it impossible to study the geometric figures that served as the basis for their architectural design in greater depth [Arnold 1996: 39–54]. Nevertheless, the remains of the pyramids of the Middle Kingdom have allowed for the study of their geometry. In comparison with temples, pyramids are simpler from a geometrical point of view. They consist of a square base and four triangular faces, and can be measured by means of a few parameters such as the length of the side of the base, the altitude of the triangular of the face, the overall height of the pyramid, the slope of the face and slope of the edge.

To calculate the pyramids, the ancient Egyptians used simple ratios such as the proportion between the middle of the base and the height, corresponding to the usual expression of seked, which represented the ratio between the horizontal displacement (in palms) of the inclined wall and the vertical to a height of one cubit [Gillings 1972: 207–214; Arnold 1991: 10–16]. So, it is known that the first pyramid of the kings of the Twelfth Dynasty was built by Amenemhet I in Lisht, with a base of 84 × 84 m. and a height of 59 m. Accordingly, the slope of the pyramid of Amenemhet I had a very approximate ratio of 5/7 (42:59).

Although there are no reliable data on the Amenenhet II Pyramid due to the lack of remains, subsequently, Amenemhet III built his pyramid at Dahshur with a base of 105 × 105 m and a height of 75 m [De Morgan 1903: 98; Arnold 1991: 10]. And accordingly, the slope of the pyramid of Amenemhet III had a ratio of 7/10 (52.50:75). In both cases, the seked of each pyramid, the ratios 5/7 and 7/10, are similar, above and below, to the ratio between the side and the diagonal of a square, that is, the irrational number √2. Thus, in a given pyramid, let us call it “Amenemhat type” (Fig. 10), the base is a square and the sides are approximate equilateral triangles.

In all probability, Egyptian architects had to be familiar with this geometric feature when designing their kings’ pyramids. This quality is especially evident in the capstone of the pyramid of Amenemhat III, a pyramidal block of basalt which is now housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (JdÉ 35122). All the edges of the base and the sides are of the same length, about 187 cm (5 remen or 5 × 5 palms) [Rossi 2003: 208].

Bearing in mind the social differences between royal and provincial power, it is possible that in the tomb of Sarenput II there was an attempt to reproduce the proportions used in royal funerary complexes of the time. Although we do not know for certain whether the ancient Egyptians knew how to obtain these geometric figures graphically, as until the arrival of the Greeks there was no clear division between arithmetic and geometry. The use of ‘simple’ ratios could be a simple method of obtaining a good approximation, although they may have also used geometric methods. The advantage of the geometric method lay in the fact that one could easily reframe the design on site, more accurately. This only required stakes and string [Choisy 1899: 51–58].

Hypothesis on design method

Taking all this into consideration, and based on mathematical knowledge of the ancient Egyptians, we dare to propose a hypothesis of the possible method used to plan the funeral chapel of Sarenput II.

First, we think that the first decision was to fix the total volume of excavation to plan the number of workers and the duration of the work. It should be remembered that one of the functions of Egyptian architects [Kostof 1977: 10] during the construction of their buildings was to organize the constant and adequate supply of blocks of stone from the quarries to the work [Clarke and Engelbach 1930: 46–68]. Thus, from the overall volume, the general data of the tomb could be obtained: the total area of the ground plan and the average height of the tomb. Then, each of the parts might be assigned a surface and a volume by pro rata according to the importance to be given to each. Then, the detailed design of each part of the tomb would follow. Each space would be assigned a height in cubits and palms according to its volume.

For example, at the tomb BH3 at the necropolis of Beni Hasan there is a biographical inscription of Khnumhotep II, governor during the reign of Senwosret II, a contemporary of Sarenput II [Newberry 1893: Part I, 39–72, Plate XXII]. This describes in detail the construction of two wooden doors, the first one made up of one sheet, for the entrance of the tomb, and the second one made up of two sheets, for the sanctuary. Their heights were of 7 cubits and 5 cubits and two palms respectively and at the end, there is a reference to the architect of the tomb: “Foreman of the tomb, the chief treasurer, Beket” [Badawy 1966: 123–124; Breasted 1906: 288–289].

Finally, on the ground plan, the desired geometric shape for each chamber could be obtained by assigning length measurements in integers to the main (longitudinal) axis and calculating the width in proportion to that length [Kostof 1977: 10]. The width is divided equally on each side of the axis. Thus, the tomb would be planned and structured in an axially symmetric way: all architectural (and decorative) elements are arranged identically on either side of the main axis. In this way, order and balance are achieved. Furthermore, as a support for the execution of the work, sketches were likely made in detail on stone or papyrus. For example, drawings could have been made of the hypostyle hall, showing its outline, the equally spaced pillars and walls to fit the shape of the room, and the architectural elements standing on the ground plan [Clarke and Engelbach 1930: 46–68; Arnold 1991: 7–10]. The sketch could have specified measurements:

This is compatible with the practical mentality of the ancient Egyptians, which can be seen in some surviving dimensioned architectural drawings. For example, it can be seen in a sketch on ostraca of a periptera chapel [Glanville 1930; Van Siclen 1986] and, above all, in another one of a chamber with four pillars [Engelbach 1927; Reeves 1986].

However, we must note that we will probably never know for sure how the funeral chapel of Sarenput II was really planned.

Conclusions

Throughout the article we have analysed the funeral chapel of Sarenput II, first studying the general relations in terms of volume and surface area of the different spaces. Later, we have focused on the geometry and proportions of its main parts, the hypostyle hall and the sanctuary. From this analysis the following results can be highlighted:

General ratios

Approximately, the total volume of the excavation is 3,750 cubic cubits, the surface area of ground taken up is about 500 square cubits and the average height is 7 + ½ cubits. The volume of the pillared hall is 3,000 cubic cubits, which is 4/5 = 1/2 + 1/5 + 1/10 (80 %) of the total excavated volume. The remaining volume, 1/5 (20 %), is divided in two between the cult chamber and connecting spaces (1/3, entrance tunnel, and 2/3, the corridor). The area of the pillared hall is 375 square cubits, which is 3/4 = 1/2 + 1/4 (75 %) of the total area, and the other 1/4 (25 %) is distributed among the rest of the ground plan of the funeral chapel.

Proportions of the hypostyle hall

The dimensions of the ground plan of the hypostyle hall are interrelated in a proportion which is between the ratios 5/7 and 7/10, and its width is twice the height of the chamber. The ratios 5/7 and 7/10, the Egyptian notation of which would be 1/2 + 1/7 + 1/14 and 1/2 + 1/5, respectively, could have been used as approximations to the geometric method to obtain the √2 rectangle.

According to Table 5, its dimensions in terms of length, width and height are very close to the ratios √2, 1 and 1/2, which is obtained from the square and √2 rectangle. Its ground plan is almost exactly in the shape of a √2 rectangle, the front wall has the shape of a double square and the sidewalls have the shape of two √2 rectangles joined at their short side.

Proportions of the sanctuary

The dimensions of the interior of the sanctuary are interrelated according to the proportions 5/6/7. The ratios 5/7 and 6/7 are approximations to the (Table 6) geometric shapes √2 rectangle and equilateral triangle, respectively. The ratio 6/7, whose Egyptian notation would be 1/2 +1/4 +1/14 +1/28, also could be used as an approximation for the equilateral triangle.

From all this, we can see that the use of approximations to the ratios √3/2, 1/√2 and √2/√3, which are derived from geometric shapes of √2 rectangle and the equilateral triangle and are reflected in the proportions of the sanctuary of Sarenput II, are compatible with ancient mathematical Egyptian sources.

Finally, we have proposed a hypothesis about the possible design process of the funeral chapel of Sarenput II, in accordance with ancient sources. We would like to note that our hypothesis does not claim to define the general method used by the ancient Egyptians, as our conclusions have been limited to the study of a single monument. What is proposed is a new viewpoint to take to future studies on ancient Egyptian monuments, and/or a much larger study, which would probably lead to greater conclusions.

Notes

Only one tomb of a governor of the First Intermediate Period has been successfully dated, that of Setka, a contemporary of the Dynasties IX/X, [Edel 2008: 1715-1815].

All the chronology is extracted from Ancient Egyptian Chronology [Hournungs, Krauss and Warbuton 2006].

About his titles, cfr. Personendaten aus dem Mittleren Reich [Franke 1984].

On the outer courts, See [Jiménez Serrano et al. 2014].

Plans drawn by the architect Juan Antonio Martínez Hermoso.

Measurement developed by the architect Fernando Martínez Hermoso.

Project of the University of Jaén in collaboration with the Ministry of State for Antiquities (Arab Republic of Egypt), led by Dr. Alejandro Jiménez Serrano.

Measurement checked by the architects Juan Antonio Martínez Hermoso and Fernando Martínez Hermoso.

References

Arnold, Dieter. 1991. Building in Egypt. Pharaonic Stone Masonry. New York: Oxford University Press.

Arnold, Dieter. 1996. Hypostile Halls of the Old and Middle Kingdoms. Studies in Honour of Wiliam Kelly Simpson, vol I: 39–54. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

Arnold, Dieter. 2003. The encyclopaedia of ancient Egyptian architecture. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

Badawy, Alexander. 1965. Ancient Egyptian Architectural Design. A Study of the Harmonic System. Berkeley: University of California Pres.

Badawy, Alexander. 1966. A history of Egyptian architecture. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Breasted, J.H. 1906. Ancient Record of Egypt, vol. I. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Budge, Wallis. 1888. Excavations made at Aswan by Major-General Sir F. Grenfell during the years 1885 and 1886. Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology, vol X: 4–40. London.

Ching, Francis D. K. 1982. Architecture, Form, Space and Order. (Spanish ed., Arquitectura. Forma, espacio y orden, trans. Santiago Castán. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 2012 (3rd ed.).

Choisy, Auguste. 1899. Histoire de l´Architecture. Tome I. Paris: Gauthier-Villars.

Clagett, Marshall. 1999. Ancient Egyptian Science A Source Book. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society Independence Square.

Clarke, Somers, and Reginald. Engelbach. 1930. Ancien egyptian construction and architecture. New York: Courier Dover Publications.

De Morgan, Jacques. 1894. Catalogue des monuments et inscriptions de l´Ègypte Antique. Haute Égypte. Tome Premier: de la frontière de Nubie a Kom Ombos. Vienne: Adolphe Holzhausen.

De morgan, Jacques. 1903. Fouilles à Dahchour en 1894–1895. Vienne: Adolphe Holzhausen.

Edel, Elmar. 2008. Die Felsgräbernekropole der Qubbet el-Hawa bei Assuan. I. Abteilung. Architekture, Darstellungen, Texte, archäologischer Befund und Funde. 4 vols. München: Ferdinand Schöningh.

Engelbach, Reginald. 1927. An architect’s project from Thebes. Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’ Égypte 27: 72–76.

Franke, Detlef. 1984. Personendaten aus dem Mittleren Reich (20.-16. Jahrhundert v. Chr.). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

Glanville, Stephen R.K. 1927. The Mathematical leather roll in the British museum. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 13: 232–238.

Glanville, Stephen R.K. 1930. Working plan for a shrine. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 16: 237–239.

Garcia Valdes, Manuela. 1996. Plutarco. Istituti Editoriali e Poligrafici Internazionali: De iside et Osiride. Pisa-Roma.

Gardiner, Alan H. 1908. Inscriptions from the tomb of Si-renpowet I, prince of Elephantine. Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 45: 123–140.

Gardiner, Alan H. 1957. Egyptian Grammar. Ashmolean Museum: Oxford. Griffith Institute.

Gillings, Richard J. 1972. Mathematics at the Time of the Pharaohs. Cambridge, Mass.: Massachusettes Institute of Technology Press.

Griffith, Francis L. 1881–2. Notes on Egyptian Weights and Measures. Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology, vol XIV: 403–450. London.

Griffith, Francis L. 1897. The Petrie Papyri: Hieratic papyri from Kahun and Gurob. London: University College.

Habachi, Labid. 1985. Elephantine IV. Verlang Philip Von Zabern: The Santuary of Heqaib. Berlín.

Hayes, William. C. 1942. Ostraca and Name Stones from the Tomb of Sen-mut (nº71) at Thebes. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Publication 15. New York.

Hournung, Erik, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warbuton. 2006. Ancient Egyptian chronology. Boston: Brill.

Jiménez Serrano, Alejandro. 2013. Los nobles de la VI Dinastía enterrados en Qubbet el-Hawa. Estudios Filológicos 337: 29-37. Salamanca.

Jiménez Serrano, Alejandro, Botella López, Miguel, Martínez de Dios, Juan L., Piquette, Kathryn E., Chapon, Linda, Torallas Tovar, Sofia, and Valenti Costales, Marta. 2014. The monumental courtyard of tomb nº 33 in Qubbet el-Hawa: preliminary report of four years of archaeological works in a middle Kingdom funerary complex. Mitteilungen des Deutsches Archäologisches Institut abtailung Kairo 70: in press.

Kostof, Spiro. 1977. The practice of architecture in the Ancient World: Egypt and Greece. The Architect. Chapters in the History of the Profession. 3–27. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lauer, Jean-Philippe. 1960. Observations sur les pyramides. Bibliothèque d’ Étude, 30. Cairo: Institut Français d´Archéologie Orientale.

Lepsius, Richard. 1865. Die alt-aegyptische Elle und ihre Eintheilung. Berlín: Druckerei der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Müller, Hans W. 1940. Die Felsengräber der Fürsten von Elephantine aus der Zeit des Mittleren Reiches. Glückstadt-Hamburg-New York: Verlag J. J. Augustin.

Newberry, Percy E. 1893. Beni Hassan. Part I. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., Ltd.

Peet, Thomas E. 1923. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus. Liverpool: University Press/London: Hodder amd Stoughton.

Reeves, Nicholas C. 1986. Two architectural drawings from the Valley of the Kings. Chronique d’ Égypte 61: 43–49.

Rossi, Corina, and Christopher Tout. 2002. Were the fibonacci series and the golden section known in Ancient Egypt. Historia Mathematica 29: 101–113.

Rossi, Corina. 2003. Architecture and mathematics in ancient Egypt. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schiaparelli, Ernesto. 1927. La Tomba intatta dell’architetto Cha: relazione sui lavori Della missione italiana in Egitto, anni 1903—1920. Torino: R. Museo di Antichità.

Schulz, Regine, and Matthias Seidel. 2005. Egipto. Könemann: Arte y Arquitectura. Barcelona.

Sethe, Kurt. 1935. Historisch-Biographische Urkunden des Mittleren Reiches. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichssche Buchhandlund.

Struve, Wassili W. 1930. Mathematischer Papyrus des Staatlichen Museums der Schönen Künste in Moskau. Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte der Mathematik 1.

Siclen, Van, and C. Charles. 1986. Ostracon BM41228: a sketch plan of a shrine reconsidered. Góttinger Miszellen 90: 71–77.

Viollet-le-duc, Eugène. 1877. Lectures on Architecture (Entretiens sur l`architecture. Paris. 1863), Eby Benjamin Bucknall, New York: Dover Publications.

Wilkinson, Richard H. 2000. The complete temples of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Martínez Hermoso, J.A., Martínez Hermoso, F., de Paula Montes Tubío, F. et al. Geometry and Proportions in the Funeral Chapel of Sarenput II. Nexus Netw J 17, 287–309 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-014-0218-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-014-0218-4