Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate gender and generational differences both in the prevalence of role conflict and in resulting career changes among married physicians with children.

STUDY DESIGN: Cross-sectional survey.

PARTICIPANTS: We sent a survey to equal numbers of licensed male and female physicians (1,412 total) in a Southern California county; of the 964 delivered questionnaires, 656 (68%) were returned completed. Our sample includes 415 currently married physicians with children, 64% male and 36% female.

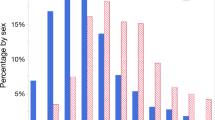

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS: The prevalence of perceived role conflict, of career changes for marriage, and of career changes for children were evaluated. Types of career changes were also evaluated. More female than male physicians (87% vs 62%, p<.001) and more younger than older female physicians (93% vs 80%, p<.01) and male physicians (79% vs 54%, p<.001) experienced at least moderate levels of role conflict. Younger female and male physicians did not differ in their rates of career change for marriage (57% vs 49%), but female physicians from both age cohorts were more likely than their male peers to have made career changes for their children (85% vs 35%, p<.001). Younger male physicians were twice as likely as their older peers to have made a career change for marriage (49% vs 28%, p<.001) or children (51% vs 25%, p<.001). The most common type of career change made for marriage or children was a decrease in work hours.

CONCLUSIONS: Most physicians experience role conflict, and many adjust their careers in response. Flexible career options may enable physicians to combine professional and family roles more effectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Gerson K. No Man’s Land. New York, NY: Harper Collins; 1993.

Nadelson CC, Notman MT, Lowenstein P. The practice patterns, life styles, and stresses of women and men entering medicine: a follow-up study of Harvard Medical School graduates from 1967–1977. JAMWA. 1979;34(11):400–6.

Le Bailley SA, Brotherton SE. Career Paths of Men and Women in Pediatrics: Descriptive Findings from the Survey on Pediatric Careers. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1988.

Callan CM, Klipstein E. Women physicians in Connecticut: a survey. Conn Med. Aug 1981;494–6.

Levinson W, Tolle SW, Lewis C. Women in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1511–7.

Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Orams J, Ewing J, Burrows G. Roles and achievement factors affecting career success of medical graduates. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;10:89–102.

Richardsen AM, Burke RJ. Occupational stress and job satisfaction among physicians: sex differences. Soc Aci Med. 1991;33:1179–87.

Di Matteo MR, Shugars DA, Hayes R. Occupational stress, life stress and mental health among dentists. J Occup Org Psychol. 1993;66:153–62.

Linn L, Yager J, Cope D, Leake B. Health status, job satisfaction and life satisfaction among academic and clinical faculty. JAMA. 1985;254:2775–83.

Driscoll MP, Ilgen DR, Hildreth D. Time devoted to job and off-job activities, interrole conflict, and affective experiences. J Appl Psychol. 1992;77:272–9.

Pleck JH, Staines GL, Lang L. Conflicts between work and family life. Monthly Labor Rev. March 1980;29–32.

Hughes DL, Galinsky E. Gender, job and family conditions and psychological symptoms. Phychol Worn Qu. 1994;18:251–70.

Drucker DG. Role conflict in women physicians: a longitudinal study. JAMWA. 1986;41:14–6.

Parcel TL, Menaghan EG. Parents’ Jobs and Children’s Lives. Hawthorne, NY: Walter de Gruyter; 1994.

Hendrick SS. Self-disclosure and marital satisfaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1981;40:1150–9.

Ricer RE. Marital satisfaction among military and civilian family practice residents. J Fam Prac. 1983;17:303–7.

Daniel C, Wood FS. Fitting Equations to Data. New York, NY: Wiley; 1971.

Gonzolez ML, ed. Socioeconomic Characteristics of Medical Practice. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association Publications; 1993;10, 11,27,40, 141.

Roback G, Randolph L, Seidman B. Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the U.S. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association Publications; 1993;12, 41–42, 75–77.

Thompson CA, Thomas CC, Maier M. Work-family conflict: reassessing corporate policies and initiatives. In: Sekaran U, Leong FT, eds. Womanpower: Managing in Times of Demographic Turbulence. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1992;61–78.

Friedman DA. Linking Work-Family Issues to the Bottom Line. New York, NY: The Conference Board; 1991;15–17.

Rieder MJ, Hanmer SJ, Haslan RH. Age- and gender-related differences in clinical productivity among Canadian pediatricians. Pediatrics. 1990;85:144–9.

Fein OT, Garfield R. Impact of physicians’ part-time status on in-patients’ use of medical care and their satisfaction with physicians in an academic group practice. Acad Med. 1991;66:694–8.

Capowski G. The joy of flex. Am Management Assoc. March 1996;12–18.

Elliott TL. Cost analysis of alternative scheduling. Nurs Management. 1989;20:42–7.

Hicks DH, Klimoski RJ. The impact of flextime on employee attitudes. Acad Management J. 1981;24:333–41.

Barker K. Changing assumptions and contingent solutions: the costs and benefits of women working full- and part-time. Sex Roles. 1993;28:47–71.

Wiersma UJ. Gender differences in job attribute preferences: work-home role conflict and job level as mediating variables. J Occup Psychol. 1990;63:231–43.

Drucker DG. Research on women physicians with multiple roles: a feminist perspective. J AMWA. 1994;49:76–88.

Woodward CA, Cohen ML, Ferrier BM. Career interruptions and hours practiced: comparison between young men and women physicians. Can J Public Health. 1980;81:16–20.

Uhlenberg P, Cooney TM. Male and female physicians: family and career comparisons. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:373–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Supported in part by grants from the UCLA Academic Senate Committee on Research, UCLA Stein/Oppenheimer Endowment, and the Long Beach Chapter of the American Medical Women’s Association.

All conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the West Los Angeles VAMC, UCLA, the Stein/Oppenheimer Endowment or the American Medical Women’s Association.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Warde, C., Allen, W. & Gelberg, L. Physician role conflict and resulting career changes. J Gen Intern Med 11, 729–735 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02598986

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02598986