Abstract

Progress in any area of biology has generally required work on a variety of organisms. This is true because particular species often have characteristics that make them especially useful for addressing specific questions. Recent progress in studying the evolutionary biology of senescence has been made through the use of new species, such asCaenorhabditis elegans andDrosophila melanogaster, because of the ease of working with them in the laboratory and because investigators have used theories for the evolution of aging as a basis for discovering the underlying mechanisms.

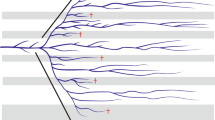

I describe ways of finding new model systems for studying the evolutionary mechanisms of aging by combining the predictions of theory with existing information about the natural history of organisms that are well-suited to laboratory studies. Properties that make organisms favorable for laboratory studies include having a short generation time, high fecundity, small body size, and being easily cultured in a laboratory environment. It is also desirable to begin with natural populations that differ in their rate of aging. I present three scenarios and four groups of organisms which fulfill these requirements. The first two scenarios apply to well-documented differences in age/size specific predation among populations of guppies and microcrustacea. The third is differences among populations of fairy shrimp (anostraca) in habitat permanence. In all cases, there is an environmentla factor that is likely to select for changes in the life history, including aging, plus a target organism which is well-suited for laboratory studies of aging.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abrams, P. A., 1993. Does increased mortality favor the evolution of more rapid senescence? Evolution, in press.

Allan, J. D. & C. E. Goulden, 1980. Some aspects of reproductive variation among fresh water zooplankton, pp. 388–410 in Evolution and Ecology of Zooplankton Communities, edited by W. C. Kerfoot. University Press of New England, Hanover, NH.

Al-Tikrity, M. R. & J. N. R. Grainger, 1990. The effect of temperature and other factors on the hatching of the resting eggs ofTanymaztix staognatus (L) (Crustacea, Anostraca). J. Therm. Biol. 15: 87–90.

Anderson, G. & S.-Yu. Hsu, 1990. Growth and maturation of a North American fairy shrimp,Streptocephalus sedi (Crustacea: Anostraca): a laboratory study. Freshwater Biology 24: 429–442.

Belk, D., 1977. Evolution of egg size strategies in fairy shrimps. Southwest. Natur. 22: 99–105.

Belk, D., G. Anderson & S.-Yu. Hsu, 1990. Additional observations on variations in egg size among populations ofStreptocephalus seali (Anostraca). J. Crust. Biol. 10: 128–133.

Belk, D. & G. A. Cole, 1975. Adaptational biology at desert temporary-pond inhabitants, pp. 207–226 in Environmental physiology of desert organisms, edited by N. F. Hadley. Dowden, Hutchinson and Ross, Inc., Stroudsburg, PA.

Belk, D., H. J. Dumont & N. Munuswamy, 1991. Studies on large branchiopod biology and aquaculture. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

Bernice, M. R., 1972. Hatching and postembryonic development ofStreptocephalus dichotomus Baird. Hydrobiologia 40: 251–278.

Broch, E. S., 1965. Mechanism of adaptation of the fairy shrimpChirocephalopsis bundyi Forbes to the temporary pond. Cornell Experiment Station Memoir 392: 1–48.

Brooks, J. L. & S. I. Dodson, 1965. Predaton, body size and composition of plankton. Science 150: 28–35.

Brown, L. & L. H. Carpelan, 1971. Egg hatching and life history of a fairy shrimpBranchinecta mackini Dexter (Crustacea: Anostraca) in a Mohave desert playa (Rabbit Dry Lake). Ecology 52: 41–54.

Browne, R. A., S. E. Sallee, D. S. Grosch, W. O. Segreti & S. M. Purser, 1984. Partitioning genetic and environmental components of reproduction and lifespan inArtemia. Ecology 65: 949–960.

Charlesworth, B., 1980. Evolution in age-structured poplations. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Comfort, A., 1960. Effects of delayed and resumed growth on the longevity of a fish (Lebistes reticulatus, Peters) in captivity. Gerontologia 8: 150–155.

Dodson, S. I., 1970. Complementary feeding niches sustained by size-selective predation. Limnol. and Oceanogr. 15: 131–137.

Dunham, H. H., 1938. Abundant feeding followed by restricted feeding and longevity inDaphnid. Physiol. Zool. 11: 399–407.

Falconer, D. S., 1989. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics, third edition. Longman, London.

Finch, C. E., 1991. New models for new perspectives in the biology of senescence. Neurobiology and Aging 12: 625–634.

Fugate, M., 1992. Speciation in the fairy shrimp genusBranchinecta from North America. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Riverside.

Gadgil, M. & W. H. Bossert, 1970. Life historical consequences of natural selection. Amer. Natur. 104: 1–24.

Goulden, C. E., R. M. Comotto, J. A. Hendrickson, Jr., L. L. Hormig & K. L. Johnson, 1982. Procedures and recommendations for the culture and use ofDaphnia in bioassay studies, pp. 139–160 in Aquatic toxicology and Hazard Assessment: Fifth Conference, ASTM STP 766, edited by J. G. Pearson, R. B. Foster and W. E. Bishop. American Society for Testing Materials.

Hall, D. J., W. E. Cooper & E. E. Werner, 1970. An experimental approach to the production dynamics and structure of fresh water animal communities. Limnol. Oceanogr. 15: 839–928.

Hall, D. J., S. T. Threlkeld, C. W. Burns & P. H. Crowley, 1976. The size efficiency hypothesis and the size structure of zooplankton communities. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 7: 177–208.

Hartland-Rowe, R., 1972. The limnology of temporary waters and the ecology of Euphyllopoda, pp. 15–31 in Essays in Hydrobiology, edited by R. B. Clarke and R. J. Wooton. University of Exeter, U.K.

Hildrew, A. G., 1985. A quantitative study of the life history of a fairy shrimp (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) in relation to the temprrary nature of its habitat, a Kenyan rainpool. J. Anim. Ecol. 54: 99–110.

Ingle, L., T. R. Wood & A. M. Banta, 1937. A study of longevity, growth, reproduction and heart rate inDaphnia longispina as influenced by limitations in quantity of food. J. Exp. Zool. 76: 325–352.

Law, R., 1979. Optimal life histories under age-specific predation. Amer. Natur. 114: 399–417.

Lynch, M., 1980. The evolution of cladoceran life histories. Quart. Rev. Biol. 55: 23–42.

Lynch, M., 1984. The limits to life history evolution inDaphnia. Evolution 38: 465–482.

Lynch, M., 1989. The life history consequences of resource depression inDaphnia pules. Ecology 70: 246–256.

Lynch, M. & R. Ennis, 1983., Resource availability, maternal effects and longevity. Exp. Geront. 18: 147–165.

Medawar P. B., 1952. An unsolved problem of biology. H. K. Lewis, London.

Michod, R. E., 1979. Evolution of life histories in response to age-specific nortality factors. Amer. Natur. 113: 531–550.

Moore, J. A., 1985. Science as a way of knowing—Genetics. Amer. Zool. 25: 1–165.

Moore, W. G., 1955. The life-history of the spiny-failed fairy shrimp in Louisiana. Ecology 36: 176–184.

Mueller, L. D., 1987. Evolution of accelerated senescence in laboratory populations ofDrosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84: 1974–1977.

Neill, W. E., 1992. Population variation in the ontogeny of predator-induced vertical migration of copepods. Nature 356: 54–57.

Newman, R. A., 1987. Effects of density and predation onScaphiopus couchi tadpoles in desert ponds. Oecologia 71: 301–307.

Prophet, C. W., 1963. Physical-chemical characteristics of habitats and seasonal occurence of some Anostraca in Oklahoma and Kansas. Ecology 44: 798–801.

Reznick, D. N., 1993. Life history evolution in guppies (Poecillia reticulata): guppies as a model for studying the evolutionary biology of aging. Experiment of Gerontology, in press.

Rose, M. R., 1991. Evolutionary biology of aging. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Rose, M. R. & B. Charlesworth, 1980. A test of evolutionary theories of senescence. Nature 287: 141–142.

Rose, M. R. & B. Charlesworth, 1981a: Genetics of life history inDrosophila melanogaster. I. Sib analysis of adult females. Genetics 97: 173–186.

Rose, M. R. & B. Charlesworth, 1981b. Genetics of life history inDrosophila melanogaster. II. Exploratory selection experiments. Genetics 97: 187–196.

Service, P. M., 1987. Physiological mechanisms of increased stress resistance inDrosophila melanogaster selected for postponed senescence. Physiol. Zool. 60: 321–326.

Service, P. M., E. W. Hutchinson, M. D. macKinley & M. R. Rose, 1985. Resistance to environmental stress inDrosophila melanogaster selected for postponed senescence. Physiol. Zool. 58: 380–389.

Service, P. M., E. W. Hutchinson & M. R. Rose, 1988. Multiple genetic mechanisms for the evolution of senescence inDrosophila melanogaster. Evolution 42: 708–716.

Spitze, K., 1991.Chaoborus predation and life history evolution inDaphnia pulex: temporal pattern of population diversity, fitness and mean life history. Evolution 45: 82–92.

Tessier, A. J., 1986. Life history and body size evolution inHolopedium gibberum Zaddach (Crustacea: Cladocera). Freshwater Biol. 16: 279–286.

Williams, G. C., 1957., Pleiotropy, and natural selection and the evolution of senescence. Evolution 11: 398–411.

Wyngaard, G. A., 1983. In situ life table of a subtropical copepod. Freshwater Biology 13: 275–281.

Wyngaard, G. A., 1986a: Genetic differentiation of life history traits in populations ofMesocyclops edax (Crustacea: Copepoda). Biol. Bull. 170: 279–295.

Wyngaard, G. A., 1986b. heritable life history variation in widely separated populations ofMesocyclops edax (Crustacea: Copepoda). Biol. Bull. 170: 296–304.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reznick, D. New model systems for studying the evolutionary biology of aging: Crustacea. Genetica 91, 79–88 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01435989

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01435989