Abstract

Mobile phones have spread rapidly over the last two decades and are now being used even in rural areas of low-income countries, where the poor are concentrated. The number of mobile phone subscriptions per 100 people in the Sub-Saharan Africa region went from 1.7 in 2000 to 82.4 in 2018, meaning that mobile phones have spread to almost all regions and all social classes. The widespread use of mobile phones has made it possible to deliver voice and text information to remote areas at a low cost and has also triggered a variety of services using mobile phones as a platform. Particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, electronic payment services on mobile phones or ‘mobile money’ rapidly spread and changed people’s lives. This significant change involves not only the urban wealthy but also the rural farmers who previously had little access to financial services. This essay summarizes the findings from the authors’ recent research on the impact of the mobile revolution on the lives of rural residents in developing economies.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The African continent, where the world’s poorest countries are concentrated, has experienced the rapid spread of mobile phones over the past two decades. According to the World Development Indicators published by the World Bank, mobile phone subscriptions per 100 people in Sub-Saharan Africa have increased from 1.7 in 2000 to 93.6 in 2020. This significant change implies that mobile phones are rapidly penetrating almost every region and social class.

The widespread use of mobile phones has made it possible to deliver voice and text information cheaply, remotely, and instantly, and triggered the emergence of various services using mobile phones as a platform. In particular, mobile money services and electronic payment services using mobile phones have been spreading quickly in Sub-Saharan Africa and changing people’s lives. This change affects the wealthy in the cities and smallholder farmers in remote areas who have minimal access to traditional financial services. Mobile money enables many more rural residents in developing countries to remit and receive money, make deposits, and borrow cheaply and conveniently.

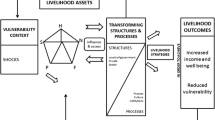

Most people in Sub-Saharan African countries have been left in financial exclusion, having very limited access to formal financial services provided by banks and other financial institutions. This is due to, among other constraints, high transaction costs, including fees for opening and maintaining accounts and the transportation cost to avail of the service. Under such circumstances, rural residents cannot save and invest effectively or borrow at low-interest rates. As a result, they have limited risk-coping measures and, hence, temporary shocks, such as bad weather or illness, often negatively and severely affect their livelihood and sometimes force them to sell their productive assets or discontinue educational investment for their children. Such disinvestment has a long-term negative influence on people’s welfare. Consequently, people lose the chance to escape from the poverty trap. So, financial exclusion is one of the causes of chronic poverty. However, the dissemination of mobile phones and the accompanying development of new information and financial services, the ‘mobile revolution,’ has dramatically changed the situation.

This essay will report on the recent development of mobile phone networks and related services and their consequences, mainly focusing on the authors’ empirical research in developing countries.

2 Rapid Dissemination of Mobile Phones in Africa

As researchers on rural economies in Sub-Saharan African countries, we have witnessed dramatic changes in the social and economic environment in the last two decades. The most significant change that we observed could be the development of mobile phone networks and the widespread use of mobile phones. Currently, mobile phone networks have covered almost all areas of human activity. Indeed, our research sites in rural communities in East Africa are mostly covered. We can communicate with the village leaders and other informants in advance to make an appointment or update the local information. In the past, there was no way to contact village leaders without visiting their villages, and we often failed to meet the persons of interest in the target villages. With mobile phones, fieldwork has become much easier and more efficient than before.

The authors have been working on a research project constructing longitudinal household survey data in three East African countries (Kenya, Uganda, and Ethiopia), known as the Research on Poverty, Environment, and Agricultural Technology (RePEAT) project.Footnote 1 The project focuses on rural residents in those three countries and covers the period of the mobile revolution in the last two decades. According to the RePEAT data, Kenya has the highest mobile phone ownership rate (i.e., the percentage of households where at least one family member owns a mobile phone), which increased from 13% in 2004 to 93% in 2012 and up to 99% in 2018 among our sample households in rural communities. In Uganda, the rate increased from 4% in 2003, 73% in 2012, and 95% in 2015. In Ethiopia, although it is a little behind the curve, the rate increased significantly from 0% in 2004 to 48% in 2014. The speed at which mobile phones have been spreading shows how great the benefits of mobile phones are.

3 Mobile Phone Penetration and Its Influence on Markets

Improved access to information infrastructure in wider areas, including rural villages, has led to significant changes in the patterns of agricultural production and marketing behavior of smallholder farmers. When information can be exchanged at a low cost, transaction costs for buying and selling agricultural products shrink, and producers in remote areas, who previously could not profit from trading, have started participating in market transactions, implying expansion of the market economy through the mobile phone network. Muto and Yamano (2009), a study using the RePEAT data of the Ugandan survey, found that farmers in remote areas, who had been engaged in almost subsistence farming, started selling their products through markets where the mobile network coverage expanded. They started selling more particularly perishable agricultural products, such as bananas. Through fieldwork, we also observed that small-scale farmers in Kenya have begun producing new commodity crops, such as fruits, vegetables, and fresh flowers, for urban supermarkets and exports, which would not be possible without reducing transaction costs because of mobile phone communication with traders.

The expansion of mobile networks broadens the market economy to more remote areas by reducing transaction costs and integrating neighboring regions’ fragmented local markets. When markets in the different regions are separated due to high transaction costs, commodity prices are determined by each region’s supply and demand conditions. However, as they are integrated, the supply and demand conditions in the larger integrated market determine commodity prices. Thus, market integration reduces price fluctuations. In addition, mismatches between supply and demand that cause unsold goods or shortages will be reduced.Footnote 2 Therefore, market integration is generally desirable for both producers and consumers because they lead to more efficient resource allocation and reduce the risk of price fluctuations.

Moreover, market integration through improved information flow by mobile network development is strengthened by improving logistics through transportation infrastructure. As the transportation infrastructure has considerably improved in many Sub-Saharan countries (Kiprono and Matsumoto 2018), the gain from the information infrastructure improvement would be more prominent. This dramatic change in markets has been happening in many Sub-Saharan African countries through the mobile revolution.

4 Variety of Services Using Mobile Phones as a Platform

Mobile phones are used as a tool for communication and as a receiver for various services. Public organizations have offered support, and private companies have offered commercial services using the short message service (SMS). In the health sector, several healthcare-related SMS services are provided. For instance, in Kenya, Malawi, and South Africa, those infected with HIV/AIDS get SMS messages indicating the type and timing of their retroviral therapy medication. The Babyl platform allows patients to register, book appointments, and receive prescriptions and examination results via mobile phone in Rwanda.Footnote 3 In agriculture, information service companies provide subscribers the price information of agricultural products in the market and agricultural technical guidance via SMS (Aker and Mbiti 2010).

Mobile money is the most revolutionary service among those using mobile phones as a platform.Footnote 4 This electronic payment service allows users to exchange money with individuals on mobile phones without having an account at a financial institution. Indeed, even those without a mobile money account can send and receive money via shared phones. Interestingly, Sub-Saharan Africa is the region where mobile money is most prevalent globally. In 2014, 12% of adults in Sub-Saharan Africa had a mobile money account, whereas only 2% did on the world average. Moreover, mobile money account owners in Sub-Saharan Africa have grown to 21% by 2017. Nearly half reported owning a mobile money account but no other financial institution account (Demirgü-Kunt et al. 2018). Among Sub-Saharan countries, Kenya is the most advanced in terms of mobile money users, where 73% of adults have a mobile money account. Uganda and Zimbabwe follow, where about 50% of adults had an account in 2017.

In Kenya, Safaricom, the biggest mobile network operator (MNO), launched its mobile money service in March 2007. M-Pesa (M stands for mobile, Pesa for money in Swahili) quickly spread nationwide as a means of depositing and transferring money, owing to its low transaction fees and the convenience of making monetary transactions with simple operations on mobile phones. Other MNOs followed suit, and there have been multiple companies offering mobile money in Kenya, although M-Pesa has been overwhelmingly dominant.

An account can be opened in a matter of minutes at M-Pesa outlet counters in town, free of charge, by bringing your ID card. Users can also make deposits and withdrawals there (or at automated teller machines or ATMs, but only in urban areas). Once users deposit a positive balance on their accounts, they can make money transfers easily and quickly by operating a simple app embedded in the memory of the mobile phone SIM (subscriber identity module) card. They have to enter the recipient’s phone number, the amount of money to be transferred, and the PIN. When completing a transaction, they immediately receive a confirmation SMS on their phone, indicating the amount sent and the remaining balance. This process is so secure that it is indeed rare to lose money either by the customer or the clerk at the outlet. Furthermore, users need to present their photo identification at the mobile money outlet counter to withdraw cash from their account. So even if their mobile phone is stolen or lost, there is little risk of money on the account being withdrawn by someone else. Thus, many people use their mobile money accounts to protect their money. For instance, long-distance travelers deposit cash into their mobile money account before departure to avoid carrying cash while traveling and reduce possible theft risks. In general, people have very high trust in mobile money services. From a gender perspective, mobile money often provides a safe platform for women to save their money privately without spousal interference. This increases their confidence to save and increases their access to financial services.

5 Spread of Mobile Money in Rural Economies

The rapid spread of mobile money in rural Kenya in a short period is due to the improved accessibility of such services through the enrichment of mobile communication and financial infrastructure and has a lot to do with the lifestyle of the rural residents. Many rural residents in Kenya are smallholder farmers engaging in settled agriculture. Since they own only small parcels for farming, it is common to send their family members, typically adult males, to towns and cities for earnings during off-farming seasons, while the remaining adults take care of their house and children.Footnote 5 For such migrant workers, mobile money has become indispensable as a means of remittances to families at home. Before the advent of mobile money services, the only ways to send money home were wire transfers handled at post offices or hand-carried by acquaintances or the migrants themselves when they returned home. Although there used to be high risks of remittance money being lost and stolen, such risks have been eliminated by mobile money services. High demand for a remittance measure and lack of alternative financial channels can explain the dramatically rapid dissemination of mobile money in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, while penetration has been modest or slow in other parts of the world. Indeed, the RePEAT survey in Kenya, representing the rural population, shows the rapid dissemination of mobile money; 43% of farm households had already used mobile money by 2009. The figure increased to 72% in 2012.

Although a step behind Kenya, Uganda also has experienced the rapid dissemination of mobile money since the first mobile money service was launched in March 2009. Several followers started mobile money services, but currently, two MNOs have dominantly operated the service due to severe market competition. Mobile money users in Uganda have been rapidly and steadily increasing, which has been observed even in rural areas. According to the RePEAT survey in Uganda, representing the rural population, the proportion of households using mobile money was almost zero in 2007, increasing to 38% in 2012, and 70% in 2015.

6 New Services Using Mobile Money

Mobile money has become more and more popular. It has begun to be used for many other purposes besides peer-to-peer (P2P) money transfer. For example, many schools in Kenya and Uganda have accepted mobile money payments for school fees. In the past, parents of students generally had to go to the school before each school term/semester to make payments in cash. While many elementary schools are located nearby, secondary schools are often located in distant locations. So, parents can save a considerable amount of time and money by making mobile phone payments. In addition, the accounting process has been eased for the schools by receiving the fees in mobile money, which indeed is associated with greater transparency. An increasing number of people have been paying their utility bills with mobile money.

New loan and insurance products using mobile money have been designed and developed. Some digital loan products are offered by MNOs partnered with commercial banks, sometimes called ‘mobile banking loans,’ while others are done by fintech firms that develop lending platforms (called ‘digital loan apps’ or ‘mobile loan apps’) connecting borrowers with lenders and distributing loans via mobile money. As individuals open and use mobile money accounts, MNOs accumulate their history of transaction records, creating credit information for individuals. Such accumulated information and its analysis enable individuals who lacked credit history and were excluded from formal credit markets in the past to access digital loan products. At the same time, these new financial products also create new business opportunities. According to the 2021 FinAccess household survey in Kenya, representing individuals aged 16 and above, 9.3% of the population uses the credit from mobile banking loans in 2021, which is the highest share among formal loans, whereas 3.4% use credit from savings and credit cooperative organizations (SACCOs, which are local, member-based financial organizations), and 2.9% use bank loans.Footnote 6

A new type of agricultural insurance called Kilimo Salama (meaning ‘safe farming’ in Swahili) was offered as a trial product to small-scale farmers in Kenya in 2011. It was indexed insurance, which covered input cost for crop production when excess rain or drought would occur, and used precipitation information from the nearest rainfall monitoring station to determine the payment of insurance claims. Thus, it did not need an inspection of the crop damage incurred by policyholders. Hence, it could be provided at a low insurance premium. In addition, the use of mobile money for claim payments further reduced costs. It made the insurance available even to small-scale farmers, who had been most vulnerable to weather risks and excluded from the market in the past. Index insurance products have drawn considerable attention since they cause less adverse selection and moral hazard than traditional insurance products. That is because insurance payments of index insurance are determined by the level of the objectively observed index rather than the actual damage reported by policyholders. Despite the high potential welfare gain for policyholders from the new insurance product reducing their weather risks, the trial has not been scaled out, as far as we know. Although the service provider did not report the details, low demand for the insurance product may be the reason for termination. Fukumori et al. (2022) examined the determinants of the product’s take-up and found that a better understanding of the insurance product enhances take-up. Low demand for the index insurance products has been reported in some cases. The basis risk, or weak correlation between the index and the actual loss incurred by policyholders, has attracted attention as a factor in lowering demand (Hill et al. 2019; Janzen and Carter 2019).

Mobile phone dissemination and the associated development of mobile financial services have significantly influenced aid organizations. They may fundamentally alter humanitarian and development assistance measures in the near future. For example, a pilot program in Niger distributed emergency relief funds using mobile money to residents in the areas suffering severe weather shock damage (Aker et al. 2016). Typically, relief supplies are procured in-kind outside, distributed to aid disaster areas, and provided to victims. There are several issues causing inefficiency in the implementation of such aid programs. First, the diversion or elite capture of relief supplies often occurs and reduces the amount of supplies delivered to victims. Second, the delivery of supplies is delayed. Third, relief supplies from the outside could crowd out local suppliers and distributors. However, the direct remittance of aid to the victims in the affected areas via mobile money will greatly reduce implementation costs and improve the efficiency of aid programs. In addition, potential crowding out could be averted by business opportunities created by local business entities to sell their commodities via the platform. Furthermore, the physical and mental burden on the victims will be reduced as they will not have to travel far and wait in long lines to receive relief supplies. There is also the advantage that each recipient can purchase the commodities they want according to their own circumstances.

More and more humanitarian fund transfer programs utilizing mobile money have been implemented recently for those severely suffering from natural disasters in Haiti, Afghan refugees in Pakistan, and refugees and returnees in Rwanda. The GSM Association (GSMA 2017) reported the outcome and lessons from such assistance programs and found that disbursing aid funds has the high potential to benefit recipients with timely payment, humanitarian organizations with increased traceability and efficient delivery, and mobile money providers with more customers. The full potential can be utilized where the mobile money ecosystem exists; that is, recipients have a mobile phone and a mobile money account, mobile money agents are located near recipients and keep enough liquidity, and merchants accept mobile money payments. Londoño-Vélez and Querubín (2022) evaluated a program distributing an unconditional cash transfer of about USD 19 to 1 million poor households during the COVID-19 pandemic and found that the program had a significantly positive but modest impact on the households’ well-being. Through the program, Columbia achieved rapid dissemination of mobile money. Benerjee et al. (2020) examined the effects of universal basic income in Kenya during the pandemic and found a significant but modest improvement in the well-being of the recipients.

Governments have also engaged in the development of mobile money payment systems proactively. Besides their policy and regulatory roles, government institutions in many African countries have increased the range of public services offered via digital platforms, including digitizing public services (e.g., birth certificates and national IDs) and payment via digital platforms like mobile money. Electronic declaration and digital payment of taxes in Uganda, Rwanda, and other countries are examples of such efforts by revenue authorities. As a result, taxpayers benefit from increased efficiency and reduced time and cost of tax payment. At the same time, the revenue authorities benefit from reduced incidence of tax evasion and delayed payments, and greater domestic resource mobilization.

6.1 Mobile Money’s Impact on People’s Livelihood in Developing Countries

Observing dramatic changes in the financial environment in developing countries after the emergence of mobile money services, a growing body of academic literature has evaluated the influence of access to mobile money on people’s livelihood in developing countries. In this section, we want to share the findings mainly from our research on mobile money and its impact on the livelihood of rural societies in developing countries.

6.2 Welfare Impact of Mobile Money

We investigated the impact of access to mobile money on household welfare measured by per capita consumption using the 2009 and 2012 waves of the RePEAT panel data in Uganda (Munyegera and Matsumoto 2016). The study covered a period from the onset of mobile money services in the country when almost nobody used mobile money to the transition stage when about 40% of households started using it. To identify the causal effect of access to mobile money, we utilized the panel structure of the household data tracking the same households during the period of rapid dissemination of mobile money in rural Uganda. Using a combination of household fixed effects, instrumental variables, and propensity score matching methods, we controlled for possible selection biases caused by unobserved factors that simultaneously affect mobile money adoption and outcome variables. Then, we found a positive and significant effect of mobile money access on real per capita consumption. The mechanism of this impact is the facilitation of remittances. Our preferred estimates indicated that households with at least one mobile money subscriber are 20 percentage points more likely to receive remittances from their members in towns and cities. As a result, the total annual value of the remittances they received was 33% higher than their non-user counterparts. We attribute this impact to reducing the transaction, transport, and time costs associated with mobile phone-based financial transactions. This study suggests significant welfare benefits of access to affordable financial services, which might go afield in reducing poverty and vulnerability, especially among the rural poor.

We also found that mobile money use increases the likelihood of saving and borrowing, besides receiving remittances (Munyegera and Matsumoto 2017). The corresponding amounts of each service are also significantly higher among mobile money user households relative to their non-user counterparts. The results imply that developing and enhancing access to and usage of pro-poor financial products could be a first step to achieving greater financial inclusion.

6.3 Healthcare Access and Mobile Money

Cash flow through mobile money eases the credit constraint on rural households and, hence, it is expected to positively affect several aspects of their lives, other than consumption. For example, many expectant mothers in developing countries do not receive adequate care during pregnancy due to financial constraints. If such hurdles in accessing healthcare can be overcome, it will reduce maternal and newborn mortality. Using the RePEAT data, Egami and Matsumoto (2020) looked at the impact of mobile money on access to health services, particularly maternal healthcare, in rural Uganda. They hypothesized that mobile money adoption would motivate rural Ugandan women to receive antenatal care. Utilizing a unique panel dataset covering the period of mobile money dissemination, they applied community- and mother-fixed effects models with heterogeneity analysis to examine the impact of mobile money adoption on access to maternal healthcare services. They found suggestive evidence that mobile money adoption positively affected the take-up of antenatal care. Heterogeneity analysis indicated that mobile money benefited geographically challenged households by easing their liquidity constraint as they faced a higher cost of traveling to distant health facilities. This study suggests that promoting financial inclusion by means of mobile money motivates women in rural and remote areas to make antenatal care visits.

6.4 Educational Investment and Mobile Money

The Uganda RePEAT data shows that health shocks are rampant in rural households and negatively correlate with economic activity and educational investment. For example, those who reported fever episodes and chronic diseases could not engage in income-earning activities for 7 days and 12 days, respectively, on average. They also experienced a significant income loss, which appeared to be associated with low educational investment among households with school-age children. Tabetando and Matsumoto (2020) examined the impact of mobile money adoption on rural households’ educational investment, particularly when they face health shocks. They found that mobile money user households mitigated the negative impact of health shocks on per-child educational expenses by having an increased remittance receipt. They also found that mobile money user households received remittances from more senders than non-user households. It implies that the user households are financially connected to a larger family and social network, which can function as insurance when facing unexpected adverse events.

7 Conclusion: Rural Development and Financial Inclusion Through Mobile Technology

In the COVID-19 pandemic, the significance of mobile money services has been reconfirmed, particularly in the regions where people have limited access to traditional financial services. Mobile money has been used to disburse aid funds by humanitarian organizations and remittances between family and friend networks, which mitigated the most harmful consequences of the negative shocks. The biggest potential beneficiaries of mobile technologies are rural residents in developing countries. A part of this potential has been realized, and we have had the chance to witness several aspects of the impressive change in rural societies in Kenya and Uganda. Although Sub-Saharan African countries still have a lot of poverty-related challenges, many of them have developed mobile communication and financial infrastructure, and more people have been involved in this dramatic change and have had better access to financial services. There is no doubt that private businesses will be booming corresponding to this mobile revolution, coupled with improvements in transportation infrastructure after the pandemic. We strongly believe that the light of hope is gradually shining on the future of Africa. It is fascinating and fortunate for us to have the opportunity to observe this dramatic change in the mobile and financial environment closely as a researcher during this period of major transformation in Africa. This was made possible by the generosity and constant guidance of Professor Otsuka. With the hope that the era of Africa will come, we would like to continue observing what is happening on the continent.

Recollections of Professor Keijiro Otsuka

I first met Professor Otsuka in 1996 when I began my master's program at Tokyo Metropolitan University and took his class. In his class, students prepared answers to end-of-chapter questions from a microeconomics textbook in English and submitted them every week, which the professor corrected. Being new to economics and writing in English, I almost cried as I completed the homework each time. Sometimes I couldn't submit by the deadline, so I sent it by fax. The submitted essays were always filled with red ink and many comments: “This sentence doesn't make sense,” “There is a leap in logic,” among many others. I remember how happy I was on the rare occasions when I received a “well done” comment. To my surprise, Professor Otsuka is still as passionate about his research as he was then. I was very fortunate to have met him and received training from him at the beginning of my academic career, which is the biggest treasure in my life.

−Tomoya Matsumoto.

Notes

- 1.

Yamano et al. (2011) describe the details of the RePEAT project.

- 2.

- 3.

The detail is given in the following URL: https://rdb.rw/government-of-rwanda-babyl-partner-to-provide-digital-healthcare-to-all-rwandans/.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

The most common credit sources are shopkeepers and family/friends/neighbors, used by 28% and 16% of the population, respectively. The database can be accessed via the following URL: https://www.centralbank.go.ke/2021/12/17/full-2021-finaccess-household-survey-dataset/.

References

Aker JC (2010) Information from markets near and far: mobile phones and agricultural markets in Niger. Am Econ J-Appl Econ 2(3):46–59

Aker JC, Mbiti IM (2010) Mobile phones and economic development in Africa. J Econ Perspect 24(3):207–232

Aker JC, Boumnijel R, McClelland A, Tierney N (2016) How do electronic transfers compare? Evidence from a mobile money cash transfer experiment in Niger. Econ Dev Cult Change 65(1):1–37

Banerjee A, Faye M, Krueger A, Niehaus P, Suri T (2020) Effects of a universal basic income during the pandemic: technical report. University of California San Diego

Demirguc-Kunt A, Klapper L, Singer D, Ansar S, Hess J (2018) Global findex database 2017: measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank, Washington, DC

Egami H, Matsumoto T (2020) Mobile money use and healthcare utilization: evidence from rural Uganda. Sustainability-Basel 12(9):3741

Egami H, Mano Y, Matsumoto T (2021) Mobile money and shock-coping: urban migrants and rural families in Bangladesh under the COVID-19 shock. HIAS Discussion Paper Series

Fukumori K, Arai A, Matsumoto T (2022) Risk management for smallholder farmers: an empirical study on the adoption of weather-index crop insurance in rural Kenya. JICA Ogata RI Working Paper No. 230

GSMA (GSM Association) (2017) Landscape report: mobile money, humanitarian cash transfers and displaced populations. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/resources/mobile-money-humanitarian-cash-transfers/

Hill RV, Kumar N, Magnan N, Makhija S, de Nicola F, Spielman DJ, Ward PS (2019) Ex-ante and ex-post effects of hybrid index insurance in Bangladesh. J Dev Econ 136:1–17

Jack W, Ray A, Suri T (2013) Transaction networks: evidence from mobile money in Kenya. Am Econ Rev 103(3):356–361

Janzen SA, Carter MR (2019) After the drought: the impact of microinsurance on consumption smoothing and asset protection. Am J Agr Econ 101:651–671

Jensen R (2007) The digital provide: information (technology), market performance, and welfare in the South Indian fisheries sector. Q J Econ 122(3):809–924

Kiprono P, Matsumoto T (2018) Roads and farming: the effect of infrastructure improvement on agricultural intensification in South-Western Kenya. Agrekon 57:198–220

Londoño-Vélez J, Querubín P (2022) The impact of emergency cash assistance in a pandemic: experimental evidence from Colombia. Rev Econ Stat 104(1):157–165

Mugizi FMP, Matsumoto T (2020) Population pressure and soil quality in Sub-Saharan Africa: panel evidence from Kenya. Land Use Policy 94:104499

Munyegera GK, Matsumoto T (2016) Mobile money, remittances, and household welfare: panel evidence from rural Uganda. World Dev 79(25101002):127–137

Munyegera GK, Matsumoto T (2017) ICT for financial access: Mobile money and the financial behavior of rural households in Uganda. Rev Dev Econ 22(1):45–66

Muto M, Yamano T (2009) The impact of mobile phone coverage expansion on market participation: panel data evidence from Uganda. World Dev 37(12):1887–1896

Suri T, Jack W (2016) The long-run poverty and gender impacts of mobile money. Science 354(6317):1288–1292

Tabetando R, Matsumoto T (2020) Mobile money, risk sharing, and educational investment: panel evidence from rural Uganda. Rev Dev Econ 24(1):84–105

Yamano T, Otsuka K, Place F (2011) Emerging development of agriculture in East Africa: markets, soil, and innovations. Springer, Berlin

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Matsumoto, T., Munyegera, G.K. (2023). Mobile Revolution and Rural Development. In: Estudillo, J.P., Kijima, Y., Sonobe, T. (eds) Agricultural Development in Asia and Africa. Emerging-Economy State and International Policy Studies. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5542-6_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5542-6_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-5541-9

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-5542-6

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)