Abstract

The banking industry in Europe is being changed by the emergence of new technologies, new players, and favorable regulatory frameworks such as the European Commission’s Payment Service Directive 2 taking effect in 2018.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The banking industry in Europe is being changed by the emergence of new technologies, new players, and favorable regulatory frameworks such as the European Commission’s Payment Service Directive 2 taking effect in 2018. FintechsFootnote 1 have allowed the introduction of new services and have changed the way of interacting with customers to satisfy their financial needs. TechfinsFootnote 2 have followed.

The Fintech landscape is constantly evolving. Different business value propositions are entering the financial services industry, ranging from enhancing user experience to developing a time-to-market framework for banks to innovate products, processes, and channels of contact, improving cost efficiency and looking to “partner on order” to lighten regulatory burdens. In many areas of business, banks are changing their value chain structures and adjusting their business models accordingly. Strategists no longer take value chains as a given. Banking is shifting significantly from a pipeline, i.e., vertical paradigm, to open banking where open innovation, modularity, and ecosystem-based banking business models become the new paradigm to follow and exploit. In such an environment, which continues to evolve under the impact of digital technologies, opportunities and threats for banks are manifold. More than ever, technologyFootnote 3 has become a strategic choice. It will decide the future of banking and the degree to which intermediary financial institutions like banks can redefine their role in the market.

This chapter analyzes the above developments by looking at banking in continental Europe. Section 2 describes the traditional banking business model and its evolution, and outlines the renewed interest in retail banking. Section 3 covers the digital transformation in banking and the role regulation plays in this process, while Sect. 4 describes the stages of this digital transformation. Section 5 explains where banks and Fintechs currently stand, and provides examples of opportunities for new forms of collaboration. Finally, Sect. 6 presents a brief conclusion and describes upcoming challenges for the industry.

2 Retail Banking from Past to Present

In every country, banks have long played an important role in providing answers to customers’ financial needs (Office of Fair Trading, 2010). However, the underlying business models were not uniform, neither across countries nor over time. For example, as a response to national banking crises in the late 1920s and early 1930s, governments in the US and Japan placed considerable restrictions on the scope of business banks could conduct; the separation of commercial or retail banking from investment banking being the most important among them. In central Europe, such restrictions were not applied. The universal banking model allowed banks to provide a whole range of financial services to both private and corporate customers—deposits, loans, asset management, and payment services—with the general exception of insurance.

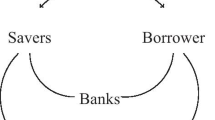

Up until the early 1970s, business activities by central European banks were nevertheless restricted by a variety of factors such as domestic regulations constraining free competition and regulating interest rates for the sake of financial stability, a fixed exchange rate regime with its corresponding restrictions on international capital transfers, and underdeveloped primary and secondary capital markets, which limited the volume of emissions and the trading of bonds and equities. However, the strong postwar growth—combined with the strong dependence of companies on loans, high household saving rates and restrictions on competition—provided incumbent players with a prosperous business environment. Applying a business model perspective, this phase is often characterized as the “production” stage (AT Chumakova et al., 2012; Kearney, 2021; KPMG, 2014; Omarini, 2015). Banks focused on “producing.” In the context of their role as financial intermediaries, this basically meant turning savings into loans while offering standardized payment services by administering customers’ current accounts. Given the strong demand for deposits, loans, and payment services, banks would not have to worry about “sales.” As a consequence, they had a predominantly inward focus and would pay little attention to the market side of their business.

After the early 1970s, when the fixed exchange rate regime faltered, macro-economic growth rates dwindled and capital market and interest rate liberalization set in, competition started to intensify. As a response, bank management began to shift their attention towards “product quality” by improving their service offerings. There was increasing recognition among banks of the necessity to identify customer needs. At the same time, also being increasingly recognized, was the need to advertise and the potential of marketing. The concept of selling and developing a sales culture became more strongly emphasized, and product promotion was given a higher strategic priority.

From the 1980s onwards, market orientation became more and more relevant as competitive threats from the financial and non-financial sectors continued to grow. However, retail banking developed in different ways and at varying speeds, although all systems shared the common trend and strategic shift toward a stronger market orientation (European Financial Marketing Association [EFMA] and Microsoft, 2010). In some countries, especially more deregulated ones like the UK, retail banks were already about to enter the final stage, the “market-led” era in which marketing drives the whole organization. In such a world, banks attempt to proactively anticipate and meet customer needs. Customer service and quality become dominant strategic concerns.

The shift from a supplier-oriented financial system in which traditional retail banks dominate, to a market-oriented system characterized by highly contestable markets in which new competitors can easily enter and erode any excess profit was brought about by technological advances, regulatory reforms, and changes in customer attitudes. This was further accelerated by the world financial crisis in 2007/2008 and in Europe by the eurozone crisis starting in 2010. As the following sections exemplify, the trends affected the business environment, the internal organization of bank holding companies, and the design of bank services and their delivery. The profound restructuring even put into question the traditional definition of retail banking as a fixed bundle of financial services related to savings, loans, and payments.

Competition in retail banking has become multifaceted as competitors enter from different industries, especially in the areas of payments and consumer loans, taking advantage not only of the above-mentioned trends, but also of incumbents’ weaknesses. In this new environment, satisfying both shareholder and customer interests is of vital importance (DiVanna, 2004; Edward et al., 1999). It means combining strategies aiming at higher productivity through cost-cutting measures with strategies aiming at enhancing customer loyalty through better service quality and improved customer convenience. However, the true challenge is how to implement such an approach in an effective manner. The execution of a real market-oriented strategy was, and still is, a weakness of traditional retail banking (Omarini, 2015).

The European Commission’s view on retail banking in Europe, including its different national structures and prospects in 2007, is articulated in the below text (see Box 1).

Box 1: The European Union (EU) Perspective on Retail Banking Before the Crisis

Retail banking is an important industry for the European economy. According to one EU document (European Commission, 2007) it represents over 50% of banking activity in Western Europe. It is estimated that in 2004, retail banking activity in the EU generated a gross income of €250–275bn, equivalent to approximately 2% of total EU GDP. As a whole, the banking sector in the EU provides over three million jobs.

Market structure differs considerably across the EU and this applies to the degree of market concentration as well as to the identity of the main players. Some retail banks have specialized origins, for instance, as mortgage or online banks and, therefore, only offer a limited range of retail banking products and services. However, there is also a growing trend in Europe, particularly among large banks, to operate as financial conglomerates in a range of financial service markets such as life insurance or asset management, as already mentioned. Another aspect to consider is market concentration. Though concentration can be described as modest in most member states, some countries such as Belgium, the Netherlands, Finland, and Sweden have significantly higher concentration ratios. Retail banking in the Benelux and Nordic countries is also characterized by significantly greater cross-border activity and, consequently, a higher degree of market integration. Other countries such as Germany or Spain are dominated by savings or co-operative banks with a strong regional focus. Subsidiaries of foreign banks have a major market presence predominantly in the new member states.

In June 2005, the European Community initiated sector inquiries into retail banking. As outlined in the EU document (European Commission, 2006), European retail banking markets were characterized by the following features:

-

A high degree of international and national regulation

-

A high level of co-operation among banks (e.g., payment infrastructures)

-

Significant market fragmentation and differences regarding market structures

-

Entry barriers due to regulatory or behavioral causes

-

A fragmented demand side (individuals, small enterprises) characterized by information asymmetry, customer immobility, and very limited bargaining power

At roughly the same time, the European Commission identified carefully two evidence-based initiatives that would bring benefits to the EU economy:

-

Investment funds

-

Retail financial services

The Commission believed that further action was needed to open up the fragmented retail financial service markets. It took a targeted and consultative approach, involving all market participants at every stage of its policymaking. In December 2005, the future strategy on financial services was presented in the White Paper on Financial Services Policy 2005–2010. This document identified as priorities the extension of better regulation principles into all policymaking and the strengthening of competition among providers, particularly in the retail banking sector. Other noteworthy findings include concerns that consumer protection rules for retail banking vary considerably across member states, which raises the cost of entering new markets and maintains market fragmentation.

Source European Commission (2007), adapted.

Before going on to discuss in detail how the digital transformation changed retail banking, three basic aspects related to banking should be noted. First, retail activities are organized along three principal dimensions: the products and services offered, customer relations, and the channels by which products and services are delivered to customers. Second, an important portion of the value that banks provide through their services is intangible. Third, the core intangible asset involved is trust. Among service providers, banks’ services enjoy a high level of trust based on their professional capabilities. It is not an overstatement to say that trust forms the foundation of the business in which banks and other financial service providers operate. The aforementioned trends and the digital transformation discussed below will not change the trust-based nature of banking.

3 Digital Transformation in Banking

There are four major driving forces changing the banking landscape today:

-

Technology

-

Regulation

-

New competitors

-

Consumer attitudes and behaviors

First, technology in banking has always had the power to impact the fundamentals of business, such as information and risk analysis, distribution, monitoring, and processing (Llewellyn, 1999, 2003). However, it can be useful to make a distinction between technologies of the past and the digital technologies of the present. The latter not only have the power to improve efficiency and effectiveness in services but have also started to exert increasing influence on banks’ products and delivery methods (European Central Bank, 1999). Digitalization also contributes to innovation leading to further improvements in profitability. Today, the capacity of a company to adapt to technology and exploit its potential depends overall on its capacity to translate those benefits into products and services, processes and new business models, and to secure and improve its competitiveness. If we take a broader industry perspective, we see that technology is also able to enhance economies of scale, thus changing the proportion of fixed versus variable costs, but also lowering entry barriers. This may increase the contestability of banking markets, and invites more agile companies to populate the banking landscape.

All of the above is possible because digital technologies are highly malleable. They open larger domains to new potential functionality (Yoo et al., 2010), introducing in every industry disruptions of various degrees. This is because they extend the innovation systems concept to the societal level (Alijani & Wintjes, 2017; Wintjes, 2016). It is on the borderless extension of financial innovation at the societal level where the big changes occur and where the new Fintech phenomenon has started developing and reshaping the industry’s value propositions and related business models.

In the literature, this is also being addressed by the term “open innovation.” Open innovation is widely understood as a process by which outside partners join in the development of innovative solutions, thus exploiting advantages of specialization, economies of scale and scope, as well as cost and risk sharing (Chesbrough, 2003, 2006, 2011; Chesbrough et al., 2014; Enkel et al., 2009). In other words, through open innovation, banks combine both internal and external resources to create new products (Chesbrough, 2011), increase the flexibility and timeliness in the way they respond to market demand and tailor their services to customers’ individual tastes (Schueffel & Vadana, 2015).

The second driving force is regulation. Digital technologies have attracted remarkable attention from legislators. Regulators and authorities, having become aware of the power and magnitude of innovation, have started to invite the financial services industry to embrace the potential of new technologies by introducing legal certainty to previously unregulated services. While after the financial crisis, compliance issues and financial stability were the main regulatory concerns, the second EU Payment Services Directive (PSD2) shifted the focus to boosting technological innovations and reshaping the industry by introducing an open banking framework with the potential to further evolve towards open finance (see Box 2).

Box 2: The Payment Service Directive 2 in Europe: a Boost Towards an Open Finance Framework

This piece of regulation was adopted in 2015 and enforced from January 13, 2018. It aims at revolutionizing the European Union payments landscape and the whole banking industry.

PSD2 represents a key contributing factor in shaping and changing the banking industry and the way financial services are conceived, produced and delivered—their value chain. The new directive encompasses several goals at different levels, including: the harmonization of payment services in the EU, putting them under common standards, the enhancement of transparency; incentives for new players introducing innovative services to enter the market; the enhancement of security standards; and increased competition and choice to benefit the consumer (EY, 2017).

In addition to consumer protection and compliance in security standards, the centrepiece of the regulation is the obligation to provide third parties, if the customer authorizes them, with access to the data and information of the payment account the customer holds within a bank. This, as intended by the European Commission, would put consumers at the very centre of the landscape, where they could freely choose among a wide array of services from different providers, as banks are mandated to open current account information and interact with all other industry players. PSD2 requires banks to enable customers to authorize licensed third parties to access their transaction history. In effect, under PSD2 banks are mandated to be able to provide “access to account” and communicate to authorized third parties, their customer and payment account information. This allows new players to thrive not only in the payments segment, but as an extension, in other segments as well once they are able to tap into account information.

Among established providers, the directive categorizes new services as follows:

-

(1)

Payment Initiation Service Providers (PISPs). They initiate the transaction and mediate between the user and his or her bank. They may establish a software bridge between a merchant's website and an online banking platform. These third parties are authorized by the customer. They can be, for example, merchants, who initiate a payment directly from the customer’s bank account to another party through use of dedicated interfaces such as application programming interfaces (APIs)—bypassing the need for a credit card transaction and thereby using direct channels into the bank.

-

(2)

Account Information Service Providers (AISPs). They access and consolidate users’ information from all their accounts under the prescription of open information. In this way, they give consumers the opportunity to review their various bank accounts on a single platform.

-

(3)

Card Issuer Service Providers (CISPs). They provide new modalities of fund checking for a payment request and the ability to issue decoupled cards.

According to competition Policy Commissioner Margrethe Vestager, PSD2 provides a legislative framework to facilitate the entry of (such) new players and ensure they provide secure and efficient payment services. This makes it easier to shop online and enabling new services to enter the market to manage (their) bank accounts, for example, as well as keeping track of their spending on different accounts (European Commission, 2015a, b).

In the literature, Cortet et al. (2016) maintain that PSD2 goes a step beyond a regulatory scope. The directive is indeed an impressive accelerator of the digitization process that has already started to appear within banking. In particular, it should be noted that this regulation would have a severe impact on revenue streams that were considered “sticky” by banks.

PSD2 is of course a further regulatory response to technological changes and behavioral changes among consumers. The directive aims at fostering a further transformation through the prescription of a higher level of openness. This in turn will accelerate the fragmentation of the value chains in the banking sector, as consumers become free to choose services provided by a third party on the basis constituted by the (open) account that they hold within a bank. Those banks, in effect, will not be the only channels through which consumers will be able to access related services, thus separating a rather sticky account service relationship from the related services that banks could sell through that (once) preferential gate. The big mindset shift needed in order to bring this about is that of making everyone aware to move from controlling to managing customers’ money (Omarini, 2019).

Source Author’s elaboration.

The move to open banking is already spreading globally, though its actual impact depends to a large extent on the regulatory environment, not only in banking, but also in areas such as open finance and the data economy. Some countries, such as Australia and Singapore, are already undertaking this further evolutionary step while others continue to study the situation.

The European Union passed another important piece of regulation useful to the implementation and reinforcement of the aforementioned one, which is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This regulation has been in force since May 25, 2018. In the EU, GDPR and PSD2 are both developing a regulatory approach to establishing a foundation for open banking.

Finally, one also needs to consider the launch of the Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS) in September 2019 aimed at strengthening customer authentication and secure communication. These standards are key to achieving the objectives of the PSD2, namely, enhancing consumer protection, promoting innovation and improving the security of payment services across the European Union. Also, in the UK, the same situation is brought about by the Competition and Markets Authority’s (CMA) Open Banking initiative, which mandates the nine largest banks in the country to provide access to banking data via a standard secure API so that personal and small business customers can manage their accounts with multiple providers through a single digital app.

The third driving force is concerned with new competitors. The potential for banks to open up a wide array of APIs and services exceeds the minimum levels mandated by legislation. Open banking enables the development of premium APIs, which, when fully developed, will allow data sharing practices to be effectively applied to a plethora of new sectors. A world without borders is becoming both an opportunity and a challenge for managers and policymakers. It is under these conditions, that technology start-ups found a way to enter the financial services industry and offer products and services directly to consumers and businesses.

Fintechs started entering the market by leveraging technology and regulation. In particular, they started targeting three retail banking areas—payments, lending, and financial advice, where they have worked at reducing the gap between what customers expect and what they actually get. In doing so, they have looked for and leveraged the relationship with customers by developing their business models in line with the following main characteristics: simplicity, transparency, ease of customer acquisition, ease of distribution, and commercial attractiveness, which refers to value creation and relationship characteristics boosting customer engagement. In contrast to traditional banks, Fintech companies share attributes, such as being young, aspirational, visionary, and capable. They are also freed from the constraints of legacy technology and tend to be highly specialized. They used to be backed by rising levels of venture capital. Recently, however, these funds have declined as investors are looking for ways to cash in on their investments.

Finally, the fourth driving force is the way consumer attitudes and behaviors are reacting to these changes while boosting them at the same time. Open finance empowers consumers to access their financial data beyond current accounts, extending for example to mortgages, credit, student loans, automotive finance, insurance, investments, or pensions and loans. Ultimately this allows for the delivery of additional value in the form of saving-related services, identity services, more accurate creditworthiness assessments, or tailored advice and financial support services. However, the success of open finance depends on customers being prepared and educated to engage, and willing to allow third-party providers access to their financial data such as transaction information.

It is worth remembering that consumers are human beings, which implies that what they want and expect from banks can only be partially defined in financial terms. Indeed, consumers want their life to be easy and the same is required for the path to their goals to be a simple one (Omarini, 2019). At present, the most common set of attitudinal and behavioral characteristics consumers show that what they demand are:

-

convenience, implying speed and timeliness, due to scarcity of time (Oliver Wyman, 2018) so that banking is increasingly done in real time and available 24/7 (Accenture, 2019)

-

product simplicity and ease of use (PwC, 2014)

-

cost savings as a result of low-income growth (Oliver Wyman, 2018)

-

personalized offerings

-

experiential and functional elements.Footnote 4

The COVID-19 pandemic has further incentivized customers’ shift away from traditional branches to using digital channels. According to BCG (Boston Consulting Group)’s most recent retail-banking survey (Brackert et al., 2021), an average of 13% of respondents in 16 major markets used online banking for the first time during the pandemic (12% for mobile). In some markets, the percentage is substantially higher. Cashless payments have also been receiving a major boost during the crisis. More than 20% of respondents reported increasing their use of digital payment solutions, such as those provided by internet banking and third-party apps, and more than 10% said the same about credit and debit cards. This shift to digital channels is likely to be permanent. Digitally savvy customers will defect to more digitally advanced incumbent competitors or nimble and innovative challengers. This presents a real risk for traditional banks.

The combination of the above factors is fundamentally transforming the industry with intensified competition and shrinking profit margins (KPMG, 2016). Bank managers can no longer focus solely on costs, product, and process quality, or speed and efficiency. They must also strive for new sources of innovation and creativity. These increasingly complex forms of competition force everyone into being in the business of being chosen by customers (Omarini, 2013) so that every business is confronted by a formidable and constant challenge. Customers are more and more aware of what is available in the market and are ever more demanding. These high expectations tend to lower the level of satisfaction. Thus, the paradox of the twenty-first century economy: consumers have more choices that yield less satisfaction. Top management, too, has more strategic options that yield less value (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004).

Today, financial products and services move onto interconnected platforms, where collaboration is becoming the new rule in offering integrated consumer banking. This new approach was neither premised on—nor measured by—volume of sales, but rather on the ability to provide solutions to customers through span of life changes: employment, unemployment, marriage, divorce, child-rearing, retirement, and so on. The result is that customers require help with a much wider range of problems, which are often influenced by emotion. Managing such customer relations entails the use of new and unfamiliar methods, such as the processing of situational information in ways that communicate a sense of care—even gossip, awareness of social responsibility, and customer education are included here.

The provision of solutions to customers through digital platforms is transforming the business ecosystem. A business ecosystem is a community of interacting entities. These entities can be organizations, businesses, or individuals, which create value for one another by producing or consuming goods and services that support each other mutually. Digital platforms are able to reduce transaction costs related to the interaction between different entities. In this way, the ecosystem will become more integrated and agile.Footnote 5

For retail bankingFootnote 6 in Europe, the advent of digital platforms can be expected to cause a shift away from the traditional universal bank business model in which economies of scale and scope dominated strategic thinking and where conflicting interests between business sections could easily arise within the same legal entity, toward a new customer-centered universal banking model (integrated consumer banking) in which unbundling and re-bundling of services and respective business models are chosen for a purpose, i.e., solving a customer’s use case or improving quality and customer experience. The focus will be more and more on customer needs and not on what banks can and may want to sell to the market. This means organizing around value streams and developing a series of value-adding activities that lead to overall customer satisfaction. The new banking paradigm is supported by the open banking and finance frameworks, the digital environment and the increasing role banks might play in re-bundling fragmented financial services in the evolving banking landscape.

4 The Future of Banking

4.1 The Future of Banking is Digital

All the elements cited above make it clear that technology is transforming the fundamental value chain of financial services and, unlike in other industries, is affecting at the same time both the “production” as well as the “distribution” phases. The pillars on which the old banking model was built were “differentiated distribution” and “commoditized products.” In contrast, at present, the basis of the new banking model situation is “commoditized distribution” and “differentiated products.” Products are now designed to address customer needs and to satisfy their desires through customization and personalization. This is because of consumer data accessibility and financial products embedded into clients’ daily lives. All this is feasible because banking is conducted predominately online, and a huge amount of people can connect to the same platform to obtain the service they want. This is the stage in which the interconnection of platforms, systems, and applications is increasing.

In the meantime, technological innovations, such as APIs and cloud computing, have raised the contestability of banking markets, while the developments of technology have reduced the significance of entry and exit barriers in the banking industry. This is the advent of technology combined with the unbundling of products and services into their component parts, that have enabled new entrants to become competitive within the industry. Indeed, this unbundling has given new players the possibility to deliver their innovative solutions without undertaking all of the processes involved in a particular service and to enter the business without the substantial fixed costs involved in certain processes.

In this ever-changing scenario, to remain competitive, banks need to make new strategies and Fintechs need to make their business models more profitable and resilient to the many risks related to their specific business arena (payments, lending, investment, etc.) and those under the umbrella name of cyber risks. For example, they have to move from freemium to premium pricing; that is to say, move away from a pure free pricing model and push customers to pay for the value delivered. However, they also have to actively select customers and drive their future actions from customer acquisition to customer retention.

In the following, I outline three main stages within which the financial industry is undergoing its deep transformation: the “unbundling” stage; the “fragmentation” stage, and the “cooperation/partner” stage.

4.2 Three Stages of Evolution

The first stage is characterized by the entry of Fintech in the market arena, when they were seen as “disrupters.” They entered the market by focusing on a set of specific businesses from the vast retail banking arena (such as payments and lending). The unbundling wave separated the financial services value chain into different modules of products or services with the peculiarity of developing infinite ways of combining them. This is when we may say the industry began reconsidering its shift from a vertically integrated business (pipeline business modelFootnote 7) to a fragmented distribution of financial services where the business model framework is that of a platform structure, in which different actors—producers, consumers, etc.—connect and conduct interactions with one another using the resources provided by the platform. Some industry experts argue that the traditional pipeline business model will be squeezed out (Deutsche Bank, 2017), while others suggest that the “platformization” of the economy will continue but that the traditional business model will continue to exist at the same time thanks to the fact that pipeline companies are less complex and provide owners with more control (Pan and van Woelderen, 2017).

The second stage is characterized by a situation strictly linked to the way customers react to newcomers. The more customers are looking for a fresh choice, multi-experiences, simplification, best-of-breed products as well as personalization, the more the market has to advance. As a consequence, re-bundling offerings is the norm. Under these circumstances, on the one hand, Fintechs are under considerable pressure to engage in re-bundling activities to retain customers. On the other hand, incumbents need to close the gap in customer experience and satisfaction. In this stage, some banks have started considering Fintechs as valid partners to boost their capabilities to develop innovation thus considering the open innovation approach as an effective way to develop time-to-market solutions. Partnerships and value co-creation with other players will pave the way to the banks’ overall mission to transform innovation into superior customer experience and to reach a more cost-efficient situation that finally improves their profitability.

Banks seeking to claim a solid position in the open banking landscape will need to move beyond merely offering high-quality documentation, sandboxes, developer tools, and seamless access to APIs. Most importantly, they need to build, grow, and nurture their open banking community to strengthen their position and accelerate their commercial efforts. Specifically, banks are in a position to increase the number of developers using their APIs, obtain more direct input and feedback, signal intent for innovation, and collaborate with the aim of developing relevant products and services. Overall, this contributes to better facilitation of API ideation and use-case development to drive reach and adoption among end users.

Finally, in the third stage, business ecosystems evolve as a way of acquiring, engaging, and retaining customers. In platform businesses, ecosystems are more agile in reacting to customers’ demands and are able to reach large masses of people. It is important for banks and the financial sector in general to develop economies of scale and scope in their businesses and services. This process is accompanied to a significant degree by digital technologies. The future bank, in fact, cannot operate with the present cost structure and be competitive. Digitalized processes, increased efficiency, and cost optimization are imperative. In this connection, cloud computing is enabling organizations across the economy to innovate more rapidly by reducing barriers to entry and acquiring high-quality computing resources. More specifically, it enables more convenient, on-demand access to computing resources, e.g., networks, servers, storage, applications, and services.

4.3 Present and Future Developments in Value Chains

The nature of economic competition is changing. New players view value for customers differently and their organizations are more customer-committed than some of the traditional service providers. This is because the core business for them is the value transferred to customers through ease of access to service and a more caring system, rather than the business of controlling the entire value chain of a given product or service.

This move toward value for customers requires a change in mindset and a critical rethinking of strategy and managing business solutions within the digital ecosystem. Here, a high value is placed on networks, which requires a more holistic approach to customer knowledge as a basis for a new and wider business portfolio.

Therefore, the current outlook for the banking industry reveals a nascent set of ecosystems of independent service providers, where the traditional supply-centered oligopoly is coupled with Fintechs, Techfins, retailers, etc. At this point, PSD2 in Europe (see Sect. 3), and similar trends in other markets, are viable tools for enabling this new reality.

To make sense of these developments, there are two observations that should be considered. The first is that, like their traditional counterpart, new financial service providers aspire to develop the core purposes of financial intermediation with new methods and tools such as robo-advisory services that offer financial advice to a wider market. Parallel to this are the crowdfunding platforms that are increasing financial inclusion while also offering new investment and lending opportunities.

The second observation is that more often than not, there is still a banking organization somewhere in the Fintech stack. Just as third-party app developers rely on smartphone sensors, processors, and interfaces, Fintech developers need banks somewhere in the stack for such things as access to consumer deposits or related account data, access to payment systems, credit origination or compliance management.

As a result, two main new trends and related risks are emerging:

-

Banks and other financial service providers are relying on third-party providers more and more, which increases their mutual interconnection raising concerns about the potential risks related to this. In particular, systemic risks may arise from being “too-connected-to-fail” rather than being “too big to fail.”

-

Banking is more and more embedded in customers’ everyday lives. Therefore, the more banking will be embedded in such a way, boosted by an ever-improving user experience, the more it will be invisible to customers. That change will not occur overnight, but its seeds are already sprouting in a number of different areas. For example, banks might offer short-term loans through a given merchant that may encourage customers to buy a given product or service. Customers may believe the loan comes from the retailer, not the bank itself and the bank may be comfortable about being invisible in that transaction as long as the customer receives a good loan. The worst-case scenario would be one in which a loan is not suitable for the customer or that he or she is unable to provide the appropriate cash flow to repay it, etc. This risk may require a higher degree of transparency when financial services are embedded in a different value proposition.

Against this oncoming configuration of markets, a focus on control and ownership of resources is giving way to a focus on the importance of accessing and leveraging resources through unique models of collaboration. According to Prahalad and Ramaswamy (2004):

The co-creation process also challenges the assumption that only the firm’s aspiration matters. [....] Every participant in the experience network collaborates in value creation and competes in value extraction. This results in constant tension in the strategy development process, especially when the various units and individuals in the network must collectively execute that strategy. The key issue is this: How much transparency is needed for effective collaboration for value co-creation versus active competition for co-extracting economic value? The balancing act between collaborating and competing is delicate and crucial. (p. 197)

If co-creation is fundamental to the industry, it must draw on a wider customer perspective. This, in turn, would require introducing the idea of developing ecosystems in which the customer is truly free to move and choose the best deal in more competitive markets. These markets would let consumers make informed decisions that could offset potential market concentrations amongst market providers. This new configuration of markets represents a new paradigm of competition in which business ecosystems consist of a variety of industries with potentially increasing convergence.

5 The Changing Landscape: Where Do Banks and Fintechs Stand in the Market?

5.1 Four Strategies to Counter Fintechs

This section analyzes how incumbent banks are reacting to the threats posed by Fintechs. There are four different strategies that are the most widely used for successfully expanding a firm’s innovation portfolio (adapted from Borah & Tellis, 2014; Wilson, 2017).

-

The “hold” strategy

-

The “make” or “build” strategy

-

The “ally” strategy

-

The “M&A” strategy

First, the “hold” response means that the incumbent bank continues its business as usual, but with some revitalization to minimize potential challenges. Revitalization is a concept especially developed for product design and a way to change the life cycle. It is a technique used to give a new lease of life to an existing product by bringing it up-to-date in its design (styling), performance, costs, or other features.

Second, the “make” response implies that the incumbent bank decides to react to the new entrant’s business model innovation by developing a new product, service or another internal solution. This is possible when the traditional player has the necessary resources, capabilities, and competencies required to develop innovative solutions independently.

Third, incumbent banks can decide to confront the challenges of digitalization by cooperating with financial technology firms. Specifically, by adopting the “ally” response, the incumbent chooses to pursue a path of collaboration. Under the term “ally” are included all forms of collaboration in which the incumbent and the entrant continue as separate firms. The “ally” strategy is preferred when the perceived degree of disruption or challenge to market-centered business model innovation is low while the perceived degree of disruption or challenge to technology-centered business model innovation is high (Anand & Mantrala, 2019). Indeed, if the perceived threat posed by the Fintech to the incumbent on the market-centered dimension is low, it means that the bank is not intensively exposed to the risk of losing its core customer base. This usually happens when the incumbent has cultivated strong relationships with its clients with a high level of trust and loyalty toward the bank. However, the high intensity of technology-centered challenges means that the incumbent does not have the required capabilities and skills to easily replicate or reproduce the entrant’s new technologies in-house. It could be argued that, since the bank is not in serious immediate danger of losing its current target customers, it would be unnecessary to ally with a Fintech firm or with other companies. It can be assumed that the majority of current clients would not abandon the traditional bank’s services and products to adopt the solution created by the new Fintech company. Nevertheless, the bank may lose potential customers who may prefer technology-driven financial providers. As a consequence, some forms of alliance are mutually beneficial as both players have something the other needs: the bank needs the Fintech’s new technologies and the Fintech needs access to the bank’s large customer base, compliance competencies, and brand reputation.

A report published by McKinsey & Company (Engert et al., 2019) highlights, that alliances are becoming increasingly relevant as banking advances further into digitization and advanced analytics. Before deciding to ally with a company, incumbents need to define a clear strategic objective and business case for the partnership. Indeed, for the “ally” response to be successful, banks must delineate a pre-launch partnership structure, a methodology for evaluating each partner’s contribution and a clear and coherent vision for the end state. Moreover, they should stipulate with the counterpart governance arrangements, transition and operational support agreements, and restructuring and exit provisions (Ruddenklau, 2020).

The fourth and final strategy is the “M&A” strategy. Banks adopt the “M&A” response when they acquire a competing challenger. This means that the Fintech company is completely absorbed by the bank’s organization and only the acquiring firm remains at the end of the process. The bank usually decides to buy when it faces a double threat (Anand & Mantrala, 2019). This means that the two dimensions, i.e., the perceived degrees of disruption to market-centered business model innovation (BMI) and of disruption to technology-centered BMI, are both high. In this scenario, the incumbent is seriously threatened by the entrant’s BMI under one or more aspects of its cost-volume profit and, from a technology point of view, is unable to match and reproduce the entrant’s innovations internally. It is important to remember that the underlying condition enabling a bank to make an acquisition is the availability of financial resources and human capital. This raises the question of why the bank should mobilize a huge amount of resources in order to acquire a Fintech rather than choosing a “make” or “ally” strategy. The answer is that the “make” response may not be feasible, primarily because, for the incumbent, it would be difficult to match the challenger in technology and related competencies, while the “ally” response may not be available as the challenger may not be interested in an alliance or cooperation.

Figure 1 provides a stylized map summarizing how user needs for financial services have been satisfied traditionally, the key gaps related to financial issues, and the new Fintech solutions on offer to potentially address these problems. The aim is to verify whether all the potential sub-businesses of an incumbent bank—each responding to a different client need—are affected by the emergence of Fintech, the intensity of the potential threat as well as opportunities for collaboration.

A Fintech framework for collaborative opportunities. Source International Monetary Fund and World Bank (2019), adapted

Figure 1 shows that Fintech is having global impact on the provision of financial services, and all traditional solutions to users’ needs for financial services, activities, support, and demands. It flags the key gaps that technology seeks to fill in regard not only to all banking sub-businesses (payments, lending and borrowing), but also additional fields of insurance, wealth management, and advisory sectors. It is noteworthy that the impact of technological advances on the need for “getting advice” is relatively low, meaning that the threat in this industry is currently less intense. Traditionally, wealth managers have offered a holistic range of financial services, from investment advice to general financial planning, all based on broad expertise. Even if it is true that wealth managers are increasingly using analytic solutions at every stage of the customer relationship to increase client retention and reduce operational costs (PwC, 2016), the shift from technology-enabled human advice to human-supported technology-driven advice is happening at a slower pace. This paradigm shift can be completed only when Fintechs have developed all the required capabilities and skills and have built the level of consumer trust essential to succeed in the advisory industry. In contrast, the intensity of the threat is very high in the business areas of “pay” and “borrow.” This is in line with predictions in the above-mentioned PwC report Global FinTech survey (2016):

Payments and consumer banking are likely to be the most disrupted sectors by 2020…The payments industry has indeed experienced in recent years a high level of disruption with the surge of new technology-driven payment processes, new digital applications that facilitate easier payments, alternative processing networks, and the increased use of electronic devices to transfer money between accounts. (p. 6)

Finally, it seems that cooperating rather than competing is much more rewarding both for banks and Fintechs. As a matter of fact, on the one hand, banks can provide the Fintechs with what they now lack, be that data, brand, distribution, or technical and regulatory expertise (Belinky et al., 2015), or a large customer base, stable infrastructure, and deep pockets to fund new projects. On the other hand, Fintechs can provide incumbents with out-of-the-box thinking, technical expertise and the agility to quickly adapt to change. The limitations of Fintechs are precisely the strengths of incumbent banks and vice-versa, and the future for both of them lies in pursuing a collaborative relationship (Meere et al., 2016). By mixing the different skills and new solutions offered to the market, new data collection and data management may increase and become the most interesting and insightful byproducts that the different frameworks of collaborations may produce.

5.2 The Bank–Fintech Relationship: The Other Side of the Coin

In this section, I have described how banks’ responses to Fintechs’ challenges are affected by a multitude of factors such as cultural issues, resource availability and governance inputs, to mention only a few. In making their decision, bank managers have to weigh up the advantages and disadvantages and choose the strategy whose benefits outweigh the costs—not only in a strict economic sense, but also considering those related to change in people’s mindsets and new ways of collaborating such as agile methods of working.

The last subsection seems to suggest that collaborative strategies and partnerships between incumbent banks and Fintechs are a win–win solution. However, this assessment is far from reality. The World Retail Banking Report 2019 and the subsequent World FinTech Report 2020 describe the current situation of many bank–Fintech relationships. The former shows that only 19% of banks have a dedicated innovation team with an independent decision-making authority, only 27% find it easy to onboard Fintechs, only 21% engage with external experts for mentorship and evaluating start-up maturity, and only 21% of banks say their systems are agile enough to collaborate (Capgemini, 2019).

The latter report indicates that seven out of ten Fintech firms disagree with their bank partners culturally and organizationally, in terms of banks’ legacy infrastructures, and point out that banks’ complex processes impede Fintechs’ naturally fast-paced workstyle. Furthermore, more than 70% of Fintechs report that they are frustrated by incumbents’ process barriers. More than half of Fintech executives say they have not identified the right collaborative partner. Finally, Fintech struggle to understand banks, their business activities, their products, and their scalability, which tends to create a mismatch during collaboration, eventually even causing some projects to fail (Capgemini, 2020).

5.3 How Are Banks Responding to the Changing Game?

In this subsection, I briefly introduce how some banks are reacting to digital disruption as described in Sect. 5.1. The overall situation shows that no one approach fits all.

There is significant variation among banks in their reactions to digital disruption. However, globally, more innovative incumbent banks and financial institutions are moving rapidly to embrace digitalization. Most of them have invested heavily in transaction migration. They have also significantly upgraded web and mobile technologies and created innovation and testing centers, both in-house (e.g., J.P. Morgan) and through an innovation division separate from the broader business (e.g., Citi Fintech).

Some other banks have decided to develop new products, some of them new Fintech products in the form of end-to-end digital banking, digital investment services, electronic trading, and online cash management, while others are collaborating with Fintech companies to improve their consumer offerings. Cases of the latter are J.P. Morgan’s with OnDeck, a lending platform for small and medium enterprises that is able to process loans in a single day, Roostify, which is a mortgage process provider that makes the online lending process faster, less costly and more transparent for everyone involved, and Symphony, a solution provider for sales and trading, operations and other activities. There are many other leading banks, including those at the cutting edge of digital transformation, such as Banco Santander, Bank of America, Barclays, Banco Bilbao Vizcaya, BNP Paribas, Citi, HSBC, Royal Bank of Scotland, Société Générale, UniCredit, and Wells Fargo.

Looking at the responses and strategies covered in Sect. 5.1 reveals that the adoption of the “ally” response by large or regional banks remains debatable. On the one hand, some experts argue that regional banks, more than large money center banks, lack the economic resources required to conduct mergers and acquisitions (M&A), and sometimes also the digital resources needed to align their business with those of the acquiring entities. For these reasons, they need to have access to a wide variety of partnership opportunities, ranging from strategic partnerships to contractual alliances (Ruddenklau, 2020). On the other hand, some researchers, using hand-collected data covering the largest banks from Canada, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, have found that large, listed, and universal banks are more likely to establish alliances with at least one Fintech, as compared to smaller, unlisted, and specialized banks (Hornuf et al., 2018). In the same paper, the authors, using detailed information on strategic alliances made over a 10-year period (2007–2017), have identified two main forms of alliance: financial engagement and product-related collaboration. The former may come in the form of minority stakes in a Fintech while the latter refers to a contract-based partnership, enabling banks to broaden their portfolios. The authors have found that among the 469 unambiguously identified alliances, 39% are financial engagements with minority interest investments, 54% are product-related collaborations while the remaining 7% includes other types of interaction. Other evidence suggests that since larger banks have deeper pockets to buy Fintech firms, in the case of large banks and small Fintechs, financial engagements are more likely than product-related forms of collaboration. However, both in market-based economies (Canada and the United Kingdom) and bank-based countries (France and Germany), alliances are most often characterized by product-related collaboration, which is a comparatively less institutionalized form of alliance that offers little or no control in the Fintech product development process (Hornuf et al., 2018).

Moving from a general perspective to one of studying a specific group of banks—namely, JP Morgan Chase & Co., Citi, and Banco Santander—can provide insights into how these institutions have faced the threats posed by Fintechs.Footnote 8 The below analysis applies to the 6-year period from 2015 to mid-2020.

J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. has followed a mixed approach in which the in-house development of products and services has been completed with partners and the acquisition of Fintech companies. Citi has focused more on “make” and “ally” responses, investing in Fintechs predominately through Citi Ventures, its strategic investment and innovation arm. In contrast, the Spanish multinational financial services company Banco Santander has mainly adopted a make-oriented strategy. The majority of its acquisition and partnerships were made with the aim of acquiring the technological skills and competencies required to enhance its own existing services or build new innovative solutions internally.

Despite the differences in terms of choices adopted, it is possible to identify some common patterns between the three strategies. First, in accordance with what the PwC Banking 2020 Survey reported, the executives of the three banking institutions have made “implementing new technology” one of their main investment priorities. This is also confirmed by the fact that for all of the three banks, technology expenses have steadily increased over time. Second, with reference to the types of threats, all three strategies tried to respond effectively to customers’ changing needs, the expectation of immediacy and to the necessity of incorporating technological developments into products and services. There are numerous partnerships and acquisitions aimed primarily at gaining access to innovative technologies. Moreover, all three incumbents are aware that one of the most important challenges they face as a sector is digital disruption so that they must be able not only to offer their services in the most agile and simple way possible, with personalized and customized products, but also understand clients’ new consumption patterns and anticipate their needs, which change faster than ever before. Finally, the openness of the three banking institutions towards technological innovations, their use of technology to connect people, and their organizations and resources, make it clear that they have all adopted a platform business model.

Turning now to the critical factors driving banks’ responses, the three banks have shown that the need to accelerate innovation processes can be considered the main factor leading institutions to embrace Fintech solutions. Nonetheless, the statements expressed by Fintech executives when a partnership or acquisition with one of the three financial institutions is announced, reveal that expanding their networks and acquiring new potential customers are the main reasons for entering into relationships with incumbents. Related to this point, it is noteworthy that around the year 2015 they all started developing in-house initiatives. From 2016 onwards, they had added ally projects and moved later to M&A strategies.

As a last point of discussion, the study confirmed that the payment business is the one most affected by the Fintech revolution. It makes payments the business area in which the incumbents-Fintech relationship is more competitive. Indeed, many of the “make”, “ally”, and “M&A” responses were conducted within this area.

6 Outlook

As products and services are increasingly embedded in digital technologies, it is becoming more difficult to disentangle business processes from their underlying IT infrastructures. This trend is likely to continue, which means that banks will become even more dependent on technology, both at an operational and strategic level.

Retail banking will continue to become more modular, flexible, and contextual. Retail customers now expect to be able to integrate e-commerce, social media, and retail payments. As a result, services will become less visible to customers as they are increasingly embedded in and combined with non-financial offers and activities.

The competitive game is constantly spiraling into new forms. New innovative concepts of products and services enhance customer engagement. The spread of mobile devices enables the onboarding of customers to platforms where their activities generate data. Data collection and analysis span all areas of business such as advertising, financial advice, credit scoring, pricing, claims management, or customer retention. Locking customers into a given platform while granting them seamless switching across platform services, generates further data. Supported by artificial intelligence and machine learning, the analysis of the wide array of data streams will allow companies to continuously offer products and services that are increasingly better fit for purpose. Just how much additional value can be generated by knowing customers better seems to be limited only by the ingenuity of the platform company and the actors in the related business ecosystem (Omarini, 2018).

To stay in the game, banks need to reframe the way they perceive and manage value chains. Data-sharing forms are becoming the basis for competitive advantage influencing how services are conceived, produced, delivered, and consumed. Therefore, partnerships with other companies solely for the purpose of data collection can be expected to increase.

As banking moves onto digital platforms, cross-industry interconnections will increase and result in new competitive threats. Providers of banking services will come to see themselves more and more in the role of “enablers” of transactions occurring on platforms and within business ecosystems. As enablers, retail banks will shift from being “content” gatekeepers to becoming “customer” gatekeepers. However, even in this new role, trust will remain a core business asset.

As the lines between banks and Fintech companies become blurred, traditional definitions of banks and financial services become obsolete. Banks need to redefine themselves and their business. In the end, they will need to move closer to their customers. The goal is to not be perceived as an impersonal service provider, but as the individual customer’s personal bank. Such a new strategic positioning requires not only new skills and communication approaches, but also a fundamental change in the mindset of retail banks.

The above trends raise two important questions in the European context. First, will we see a full convergence of national retail banking systems? Second, will retail banking become dominated by global platform companies located mainly outside of Europe? One might expect that both answers warrant a simple “yes,” but the future remains unpredictable. As for the first question, there is certainly a strong push towards a convergence created by technology and platform structures. However, one should not underestimate the path dependencies created by national institutions such as regulatory frameworks, industry structures, consumer preferences and consumption patterns. Similarly, while the dominance of non-European platform companies cannot be denied, their position is continuously contested, and they are also constrained by the legislative and judicial powers of the EU with respect to security, privacy, and anti-monopoly regulations.

The importance of national context is apparent in the answers reported in the recent PwC Banking Survey, which asked about the perceived threats and opportunities created by non-traditional players in the banking industry (see Fig. 2). For emerging markets and Asia Pacific regions that mostly consist of countries with underdeveloped banking and financial systems, the new players are not so much challenging established structures, but rather have the opportunity to leapfrog by creating new systems without the time-consuming process of copying the traditional structures found in advanced economies. So here, a significantly higher share of respondents perceived opportunities for non-traditional players. The contrasting responses from the US and Europe suggest that US banks have more to fear from US-grown BigTech and startups than banks in Europe. The latter might feel more secure because of the protective nature of the aforementioned national institutional and regulatory frameworks as well as social and political conditions.

Source PwC (2020)

Non-traditional players: Threat or opportunity?

Notes

- 1.

Financial technology (Fintech) describes a wide array of innovations and actors in the rapidly evolving financial services environment. It covers digital and technology-enabled business model innovations in the financial sector that can disrupt existing industry structures and blur industry boundaries, facilitate strategic disintermediation, revolutionize how existing firms create and deliver products and services, provide new gateways for entrepreneurship and democratize access to financial services, but can also create significant privacy, regulatory and law enforcement challenges (Omarini, 2019). See also Chishti and Barberis (2016) and McKinsey (2020).

- 2.

According to Zetzsche et al. (2018), Techfins start with technology, data, and access to customers. Then they move into the world of finance by leveraging their access to data and customers and seek to out-compete incumbent financial firms or Fintech startups. They sell the data to financial service providers or leverage their customer relationships by serving as a conduit through which their customers can access financial services provided by a separate institution. This allows them to later develop a different strategy by providing financial services directly themselves.

- 3.

See also European Central Bank (1999).

- 4.

Both belong to the value customers assess while purchasing a given product/service. The experiential elements are related to the experience customers have when buying something, which impacts consumers’ mental processes and loyalty intentions after purchase. Experiences are inherent in the minds of everybody, and are the results of being involved in physical, emotional. and cognitive activities. Experiences come from the interaction of personal minds and events, and thus each person’s experience is unique. Functional elements, instead, are answering the customer’s need (paying, investing, managing risks, time management, etc.).

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

They have been the dominant models of business when the main business idea has been that of producing something, pushing it out, and selling it to customers; where value is produced upstream and consumed downstream, where there is a linear flow of information, data, etc., and where value is created by controlling a linear series of activities—that is the classic value-chain. Therefore, the focus is on growing sales. Goods and services delivered, and their related revenues and profits, are the units of analysis (Omarini, 2019).

- 8.

Some of this information has been retrieved from the analysis developed under my supervision of Francesca Caturano’s MsC thesis (2020).

References

Accenture. (2019). The dawn of banking in the post-digital era. https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/PDF-99/Accenture-Banking-Technology-Vision-2019.pdf

Alijani, S., & Wintjes R. (2017). Interplay between technological and social innovation (Simpact Working Paper Vol. 2017 No.3), SIMPACT Project.

Anand, D., & Mantrala, M. (2019). Responding to disruptive business model innovations: The case of traditional banks facing fintech entrants. Journal of Banking and Financial Technology, 3(1), 19–31.

Belinky, M., Rennick, E., & Veitch, A. (2015). The Fintech 2.0 paper: Rebooting financial services. Santander, InnoVentures, in collaboration with its partners Oliver Wyman and Anthemis Group.

Borah, A., & Tellis, G. J. (2014). Make, buy, or ally? Choice of and payoff to alternate strategies for innovations. Marketing Science, 33(1), 113–133.

Brackert, T., Chen, C., Colado, J., Poddar, B., Dupas, M., Maguire, A., Sachse. H., Stewart, S., Uribe, J., & Wegner, M. (2021, Janurary 26). Global retail banking 2021. The front-to-back digital retail bank. Boston Consulting Group. https://web-assets.bcg.com/89/ee/054f41d848869dd5e4bb86a82e3e/bcg-global-retail-banking-2021-the-front-to-back-digital-retail-bank-jan-2021.pdf

Capgemini. (2019). World Retail Banking Report 2019. https://www.capgemini.com/news/world-retail-banking-report-2019/

Capgemini. (2020). World FinTech Report 2020. https://www.capgemini.com/news/world-fintech-report-2020/

Chesbrough, H. W. (2003). Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and benefiting from technology. Harvard Business School Press.

Chesbrough, H. W. (2006). Open business models: How to thrive in the new innovation landscape. Harvard Business School Press.

Chesbrough, H. W. (2011). Open services innovation: Rethinking your business to grow and compete in a new era. John Wiley & Sons.

Chesbrough, H. W., Vanhaverbeke, W., & West, J. (2014). New frontiers in open innovation. Oxford University Press.

Chishti, S., & Barberis, J. (2016). The book of fintech. Wiley.

Chumakova, D., Dietz, M., Giorgadse, T., Gius, D., Härle, P., & Lüders, E. (2012, July). Day of reckoning for European retail banking. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/dotcom/client_service/financial%20services/latest%20thinking/reports/day_of_reckoning_for_european_retail_banking_july_2012.pdf

Cortet, M., Rijks, T., & Nijland, S. (2016). PSD2: The digital transformation accelerator for banks. Journal of Payments Strategy & Systems, 10(1), 13–27.

Deutsche Bank. (2017). Platform replaces pipeline. Retrieved September 13, 2021, from https://www.db.com/newsroom_news/2017/ghp/platform-replaces-pipeline-en-11520.htm

DiVanna, J. A. (2004). The future of retail banking. Palgrave Macmillan.

Edward, G., Barry, H., & Jonathan, W. (1999). The new retail banking revolution. Service Industries Journal, 19(2), 83–100.

Engert, O., Flötotto, M., O’Connell, S., Seth, I., & Williams, Z. (2019). Realizing M&A value creation in US banking and fintech: Nine steps for success. McKinsey & Company.

Enkel, E., Gassmann, O., & Chesbrough, H. W. (2009). Open R&D and open innovation: Exploring the phenomenon. R&D Management, 39(4), 311–316.

European Central Bank. (1999). The effects of technology on the EU banking systems. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/techbnken.pdf

European Commission. (2006, July 17). Interim report II: Current accounts and related services.

European Commission. (2007, January 31). Report on the retail banking sector inquiry. https://ec.europa.eu/competition/sectors/financial_services/inquiries/sec_2007_106.pdf

European Commission. (2015a, March 26). Competition: commissioner Vestager announces proposal for e-commerce sector inquiry. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_15_4701

European Commission. (2015b, October 8). European Parliament adopts European Commission proposal to create safer and more innovative European payments. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_15_5792

European Financial Marketing Association, & Microsoft. (2010). Transforming retail banking to reflect the new economic environment: The changing face of retail banking in the 21st century. European Financial Marketing Association.

EY. (2017). Fintech adoption index 2017. http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-fintech-adoption-index-2017/$FILE/ey-fintech-adoption-index-2017.pdf

Frazer P., & Vittas D. (1982). The retail banking revolution: An international perspective. Lafferty Publications.

Hornuf, L., Klus, M. F., Lohwasser, T. S., & Schwienbacher, A. (2018). How do banks interact with fintechs? Forms of alliances and their impact on bank value (CESifo Working Paper No. 7170). CESifo Network.

Iansiti, M., & Levien, R. (2004a). Strategy as ecology. Harvard Business Review, 82(3), 68–78.

Iansiti, M., & Levien, R. (2004b). The keystone advantage: What the new dynamics of business ecosystems mean for strategy, innovation, and sustainability. Harvard Business School Press.

International Monetary Fund, & World Bank. (2019, June 27). Fintech: The experience so far (IMF Policy Paper No.19/024). International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers/Issues/2019/06/27/Fintech-The-Experience-So-Far-47056

Kearney, A. T. (2021). European retail banking radar 2021: Challenges and opportunities in a tumultuous year. https://www.kearney.com/financial-services/european-retail-banking-radar

KPMG. (2014, March). Business transformation and the corporate agenda. https://advisory.kpmg.us/articles/2017/business-transformation-and-the-corporate-agenda.html

KPMG. (2016, October). The profitability of EU banks: Hard work or a lost cause? https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2016/10/the-profitability-of-eu-banks.pdf

Leichtfuss, R., Messenböck, R., Chin, V., Rogozinski, M., Thogmartin, S., & Xavier, A. (2010, January). Retail banking: winning strategies and business model revisited, Boston Consulting Group.

Llewellyn, D. T. (1999). The new economics of banking. SUERF.

Llewellyn, D. T. (2003). Technology and the new economics of banking. In M. Balling, F. Lierman, & A. Mullineux (Eds.), Technology and finance. Challenges for financial markets, business strategies and policymakers (pp. 51–67). Routledge.

McKinsey. (2020). Detour: an altered path to profit for European Fintech. Retrieved on September 13, 2021 from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/detour-an-altered-path-to-profit-for-european-fintechs

Meere, D., Rufat, J., Fernández, L., Gammarati, D., Morales, P., Carbonell, J., King, D., Camacho, A., Sanz, A., Torres, G., Montana, J., Russell, C., Anderson, S., & Villalante, O. (2016). FinTech & banking: Collaboration for disruption. Axis Corporate & EFMA.

Office of Fair Trading. (2010, November). Review of barriers to entry, expansion and exit in retail banking.

Oliver Wyman. (2018). The customer value gap: Re-calculating route. The state of the financial services industry 2018. https://www.oliverwyman.com/content/dam/oliver-wyman/v2/publications/2018/January/state-of-the-financial-industry-2018-web.pdf

Omarini, A. (2015). Retail banking: Business transformation and competitive strategies for the future. Palgrave MacMillan.

Omarini, A. (2017). The digital transformation in banking and the role of FinTechs in the new financial intermediation scenario. International Journal of Finance, Economics and Trade, 1(1), 1–6.

Omarini, A. (2018). The retail bank of tomorrow: A platform for interactions and financial services. Conceptual and managerial challenges. Research in Economics and Management, 3(2), 110–133.

Omarini, A. (2019). Banks and banking: Digital transformation and the hype of Fintech. Business impacts, new frameworks and managerial implications. McGrawHill.

Pan, L., & van Woelderen, S. (2017, July 6). Platforms: Bigger, faster, stronger. ING Wholesale Banking.

Prahalad, C.K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). The future of competition: Co-creating unique value with customers. Harvard Business School Press.

PwC. (2014). Bank structural reform study: Supplementary report 1: Is there an implicit subsidy for EU banks? https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/banking-capital-markets/pdf/pwc-supplementary-report-1.pdf

PwC. (2016). Blurred lines: How FinTech is shaping financial services. Global FinTech Report, March 2016. https://www.pwc.com/il/en/home/assets/pwc_fintech_global_report.pdf

PwC. (2020). Retail Banking 2020: Evolution or Revolution? https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/banking-capital-markets/banking-2020/assets/pwc-retail-banking-2020-evolution-or-revolution.pdf

Ruddenklau, A. (2020, May 8). Can fintech lead innovation post COVID-19? KPMG. https://home.kpmg/xx/en/blogs/home/posts/2020/05/can-fintech-lead-innovation-post-covid-19.html

Schueffel, P., & Vadana, I. (2015). Open innovation in the financial services sector—A global literature review. Journal of Innovation Management, 3(1), 25–48.

Wilson, J. D., Jr. (2017). Creating strategic value through financial technology. John Wiley & Sons.

Wintjes, R. (2016). Systems and Modes of ICT Innovation. European Commission. http://is.jrc.ec.europa.eu/pages/ISG/EURIPIDIS/EURIPIDIS.index.html

Yoo, Y., Henfridsson, O., & Lyytinen, K. (2010). Research commentary: The new organizing logic of digital innovation: An agenda for information systems research. Information Systems Research, 21(4), 724–735.

Zetzsche, D. A., Buckley, R. P., Arner, D. W., & Barberis, J. N. (2018). From FinTech to TechFin: The regulatory challenges of data-driven finance. New York University Journal of Law & Business, 14(2), 393–446.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 German Institute for Japanese Studies

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Omarini, A. (2022). The Changing Landscape of Retail Banking and the Future of Digital Banking. In: Heckel, M., Waldenberger, F. (eds) The Future of Financial Systems in the Digital Age. Perspectives in Law, Business and Innovation. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7830-1_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7830-1_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-16-7829-5

Online ISBN: 978-981-16-7830-1

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)