Abstract

Shakespeare would have been thrilled by all the intrigues in this relatively new and emerging financial theatre. All the elements are there to write yet another masterpiece – this time on the rise of King Microfinance, his conquering the world and the subsequent gradual decay of his empire. This case study will describe the struggle of one of the king’s knights – ACTIAM Impact Investing – in enlarging the empire in a way that simultaneously serves the interest of the people and the king’s financiers. So what happened?

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Muhammad Yunus, Nobel Peace Prize Acceptance Speech, December 2006

- 2.

Shiller, R.J., Irrational Exuberance. New York, USA, Crown Business, 2006

- 3.

Rosenberg, R., ‘Muhammad Yunus and Michael Chu debate commercialization’, CGAP Microfinance Blog, 2008

- 4.

Just to give an indication, ACTIAM managed some 46bn Euros by the end of 2014

- 5.

The problem is not only the allocation of money but also of additional resources like management attention, portfolio management capacity and reputation management.

- 6.

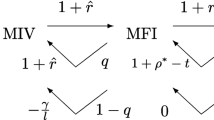

Institutional investors face a trade-off between financial only and impact investments. Based on their fiduciary responsibility institutional investors want to be compensated for their potential loss of financial return.

- 7.

See Microcredit Summit bi-annual report: http://stateofthecampaign.org/read-the-full-report/

- 8.

See MIX Market (www.mixmarket.org)

- 9.

CGAP, Cross-boarder survey on microfinance, 2012

- 10.

A distinction is made between NGOs and Non-Banking Financial Institutions (NBFIs) on one side and banks on the other. The latter received substantially more foreign investments. There were also regional differences. Latin America and the Caucasus attracted most foreign investments, while South Asia, Africa and Middle East and North Africa (MENA) were clearly lagging.

- 11.

De Sousa-Shields, M. and C. Frankiewicz (2004, p. vii) ‘Financing microfinance institutions: the context for transitions to private capital’, Micro Report, 32

- 12.

See Hrabálek, M., and Zdráhal, I., “Microfinance and the role of the State: No Pago Movement in Nicaragua”, published on line at Academia.edu

- 13.

See Sinclair, H., Confessions of a microfinance heretic, 2012, Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco

- 14.

Arunachalam, R., The Journey of Indian Micro-Finance: Lessons for the Future, Chennai: Aapti Publications, 2011. See also: Bateman, M., “How Lending to the Poor Began, Grew, and Almost Destroyed a Generation in India”, in Development and Change, Vol. 43 (6), p. 1385–1402, November 2012; CGAP, Andhra Pradesh 2010: “Global Implications of the Crisis in Indian Microfinance”, CGAP Focus Note, 67, November 2010; Wright, G.A.N., and Sharma, M.K., “The Andhra Pradesh Crisis: Three Dress Rehearsals... and then the Full Drama”, MicroSave India Focus Note 55, December 2010; Taylor, M., “The Antinomies of ‘Financial Inclusion’: Debt, Distress and the Workings of Indian Microfinance”, Journal of Agrarian Change, Vol. 12 No. 4, October 2012, pp. 601–610.

- 15.

In some cases it led to an outflow of capital at MIVs that were open-ended. Being closed-ended the ACTIAM funds were not confronted with investors reclaiming their invested capital.

- 16.

There were two exceptions: emerging market equity and hedge funds. The first dealt with a lack of reliable data available on ESG policies and performance. The second dealt with a general difficulty to assess their social, environmental and governance policies, practices and performance.

- 17.

Only producers of cluster munitions, land mines and atomic, biochemical and chemical weapons are immediately excluded. Engagement with these companies usually does not have much sense.

- 18.

Elsewhere I have argued that instead of focusing only on financial returns institutional investors can also be seen as ‘professional first’ investors. They apply professional standards to their investment processes. Investees – whether direct or through funds or mandates – have to comply with these standards in order to selected. See Hummels, H. “Impact Investing through Advisers and Managers who Understand Institutional Client Needs”, in WEF, From Ideas to Practice, Pilots to Strategy. Practical Solutions and Actionable Insights on How to Do Impact Investing, Geneva, December 2013, 40–42.

- 19.

This includes rollovers. In total the AIMFs have provided more that €850mn in debt to MFIs, which is an indication of the long-term focus of both funds. With a 7 year investment horizons the originally committed capital of €320mn has been made productive – on average – for approximately 2.5–3 years per loan. Due to the fact that many loans were rollovers ACTIAM was able to establish a long-term relationship with its MFIs.

- 20.

The SMX is created by Symbiotics. Currently the following MIVs are part of the index: ResponsAbility Global Microfinance Fund, BlueOrchard Microfinance Fund, Dual Return Fund Vision Microfinance, Wallberg Global Microfinance Fund, and Triodos SICAV II – Triodos Microfinance Fund.

- 21.

- 22.

Porter, M. E. and Kramer, M. R., ‘Creating Shared Value: How to reinvent capitalism and unleash a wave of innovation and growth’, in Harvard Business Review, 2011, Vol. 89 (1), p. 65

- 23.

The demand was triggered, among other reasons, by the changes in political and regulatory environments, which stimulated large-scale access to finance. In India, as a result of regulatory reforms the number of microfinance clients nearly doubled between 2005 and 2010. See Srinivasan, N., Microfinance: The State of The Sector Report. New Delhi: SAGE Publications, 2010.

- 24.

Porter and Kramer, 2011:65

- 25.

Krishna is a district in Andhra Pradesh. In 2006 the state shut 50 branches of two of India’s largest microfinance institutions for charging “usurious interest rates” and “forced loan recovery” practices.

- 26.

No Pago can best be translated as “I do not pay”.

- 27.

For a more detailed report see https://nacla.org/news/no-pago-confronts-microfinance-nicaragua

- 28.

For more information on and references to the Andhra Pradesh crisis in 2010 please see note 14.

- 29.

- 30.

NpM Platform for Inclusive Finance, Paying Taxes to Assist the Poor? October, 2013. See http://www.inclusivefinanceplatform.nl/documents/Documents/Publications/npm%20study_paying%20taxes%20to%20assist%20the%20poor.pdf

- 31.

MS Sriram, ‘The AP Microfinance Crisis 2010: Discipline or Death?’ VIKALPA, Vol. 37, Oct – Dec 2012

- 32.

H. Sinclair, Confessions of a Microfinance Heretic, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, July 2012

- 33.

Reyes Jr., G. De los, and Scholz, M., “Creating legitimacy and shared value with SWONT”, in Lenssen, G., and N.C. Smith, (eds.), Managing Sustainable Business,...

- 34.

To avoid misperceptions about the intentions of the asset manager, the trips were paid for by the investors. Inviting participants was not a facilitation payment to induce investors to become loyal supporters of the funds.

- 35.

Part of the problem with De los Reyes and Scholz’ approach is that they fail to clarify what normative analysis and discourse entails and what it adds to the toolbox of socially, ethically, or environmentally streetwise managers. A contribution that does provide relevant support is Mitchell, Agle and Wood’s Theory of Stakeholder identification and salience, focusing on power, urgency and legitimacy of stakeholders and their claims. See Mitchell, R.K., Agle, B.R. and Wood, D.J., “Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts”, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Oct., 1997), pp. 853–886. Useful are also Frederick, W.C., From CSR1 to CSR2: The Maturing of Business-and-Society Thought, Working paper no. 279,6, University of Pittsburg, 1978 and Ackerman, R.W., ‘How companies respond to social demands’. In: Harvard Business Review, July–August, 1973

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hummels, H. (2019). Microfinance as a Shakespearean Tragedy: The Creation of Shared Value, While Acting Responsibly. In: Lenssen, G.G., Smith, N.C. (eds) Managing Sustainable Business. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1144-7_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1144-7_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-024-1142-3

Online ISBN: 978-94-024-1144-7

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)