Abstract

This chapter introduces both internal control and organizational culture in order to provide a basic understanding for the two topics. Before addressing organizational culture in the second part of this chapter, the focus is set on internal control. A wide range of control concepts exist in the management accounting and control literature: strategic control, management control, internal control, and control systems, to name just a few of the major themes. The variety of concepts, their different purposes in closely related areas, and particularly the different interpretations from the various authors, generate many overlaps between concepts.1 As a result, differences in terminologies often cause miscommunication and misguided expectations among the parties involved.2 To understand the reason for the variety of definitions of internal control itself, the term will be embedded in its historical evolution and divided into a focused and a comprehensive view of internal control. In addition, internal control will be discussed and integrated with strategic control, management control and control systems in order to provide a holistic understanding of the fundamental role of internal control for any business. Spending adequate time for defining internal control provides the basis for investigating the role of organizational culture for internal control throughout this study.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Merchant and Otley (2007) provide an overview of different control areas in their review of the literature on control and accountability.

- 2.

Additional misunderstandings on the term control are more linguistic in nature. For example, while in the English language the term ‘control’ covers proactive (e.g., directive, preventive controls) and reactive controls (e.g., detective and corrective controls), in the German language the term ‘Kontrolle’ is usually understood only as reactive control (Ruud and Jenal, 2005, p. 456).

- 3.

Maijoor (2000, p. 105). See also Power (1997).

- 4.

For example, the Securities Act of 1933 addressed internal control and the audit process in the following words: “In determining the scope of the audit necessary, appropriate consideration shall be given to the adequacy of the system of internal check and internal control” (Early Regulation SX Rule 2-02 (b) of the 1933 Act, quoted after Ferald Fernald (1943, p. 228). A later and broader approach by the American Institute of Accountants (AIA) defined that “Internal control comprises the plan of organization and all of the co-ordinate methods and measures adopted within a business to safeguard its assets, check the accuracy and reliability of its accounting data, promote operational efficiency, and encourage adherence to prescribed managerial policies” (AIA 1948, quoted after Heier et al. 2005, p. 48).

- 5.

Brown (1962, p. 696).

- 6.

Dicksee (1892, p. 6), quoted in Heier et al. (2005, p. 42).

- 7.

Heier, Dugan, and Sayer discuss internal control in the context of auditing and its impact on audit engagements.

- 8.

For example, Brickey (2006), Rockness and Rockness (2005), Stewart (2006).

- 9.

At that time, in the US regulation addressing internal control was limited in scope as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 (FCPA) represented the only regulatory requirement for internal control reporting. The purpose of SOX was to restore public confidence in the capital markets by enhancing the reliability of financial reporting and the effectiveness of corporate governance by addressing management’s responsibility for financial reporting as well as the scope and nature of the audit (Ge and McVay 2005, p. 139).

- 10.

Coates (2007, p. 96) and Mintz (2005, p. 595). In Europe, the extraterritorial influence of SOX was discussed and debated critically. In the European Union the Eight Directive addresses internal control and risk management as well. As most European countries take a more principles-based approach, the European approach is less detailed. In Switzerland, as a non-EU member, a new regulation requires the auditor to prove the existence of the internal control system.

- 11.

An early example of such a discussion on the broadness of internal control can be given with the question whether administrative controls should be part of the audit or not. The American Institute of Certified Public Accountant (AICPA 1958, pp. 66-67) states that “[administrative controls] ordinarily relate only indirectly to the financial records and thus would not require evaluation”. However, in the event these controls have “an important bearing on the reliability of financial records”, then the auditor should consider including these controls in the assessment. Thus the discussions in the 1950s are still accounting oriented but already were concerned about the broadness of internal control. As will be discussed in this section, the debate about a broadening of the interpretation of internal control will be continued later in the twenty-first century.

- 12.

A similar distinction is taken by Jenal (2006, p. 3) who divides definitions on internal control into a focused view (focusing only on financial reporting) and a comprehensive view (focusing on operations, financial reporting and compliance).

- 13.

Throughout this study the terms internal control, internal controls, and controls are treated as synonyms.

- 14.

See Kinney (2000a).

- 15.

Simons (1995, pp. 84-85).

- 16.

Simons (1995, pp. 85-86).

- 17.

See Kinney (2000a), Pfaff and Ruud (2007), Pfaff et al. (2007), and Simons (1995).

- 18.

See O’Reilly and Chatman (1996).

- 19.

Ge and McVay (2005, p. 139). In the late 1980s the collapse of Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) caused a financial panic spanning four continents and involved the Bank of England (see Mintz 2005).

- 20.

The Treadway Commission addressed internal control aspects such as the control environment, code of conduct, audit committees, and internal audit. It also called for additional internal control standards and guidance, and suggested that all listed companies should be required to include a report on internal control in their annual reports (COSO 1992, p. 96).

- 21.

COSO (1992, p. 97). The COSO framework is summarized in Sect. 3.2.2.

- 22.

Emphasis added.

- 23.

Pfaff and Ruud (2007, p. 19). A reason for this broad acceptance might be that there is generally more awareness for the fact that internal control is more than finance and accounting, but is pervasive throughout all areas of the organization. The COSO definition has a broad foundation in the US as the Treadway Commission was established as a collaborating sponsorship among the relevant institutions in accounting, control and auditing, including the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), American Accounting Association (AAA), Financial Executives International (FEI), The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) and the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA).

- 24.

The Guidance on Control Board is associated with the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA) and issues the CoCo control framework (see CoCo 1995b and Sect. 3.2.3).

- 25.

The internal control definition of the ICAEW is from the Turnbull report, which is part of the Combined Code – A mandatory guideline for listed companies in the UK (see ICAEW 1999 and Sect. 3.2.4).

- 26.

See FEE (2005). A more specialized group such as the Information Systems Audit and Control Association, which provides the IT-governance-framework called COBIT (Control Objectives for Information and Related Technology), offers a more technical interpretation and distinguishes between preventive, detective and corrective control (see ISACA 2007). The Basle Committee on Banking Supervision describes control as something that is “continually” going on at all levels in a bank and also highlights the importance of an “appropriate culture”. BCBS is responsible for the international banking regulation and is associated with the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) and Basel II (see BCBS 1998).

- 27.

COSO (1992, p. 14).

- 28.

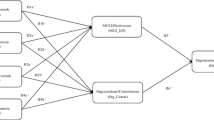

The figure is based on the COSO categories, complemented with CoCo’s “internal reporting” and “internal policies”.

- 29.

The OECD uses the term corporate governance (instead organizational governance). Organizational governance is broader than corporate governance as it can include any type of organization and not only corporations.

- 30.

Emphasis added.

- 31.

Organizational governance roots in the separation of ownership from control. According to Berle and Means (1932, p. 6), this separation leads to a condition in which the interests of owner and managers “may, and often do, diverge, and where many of the checks which formerly [in the single entrepreneurship] operated to limit the use of power disappear”. In general, the literature analyzes this separation with the agency-theory. The owner (principal) delegates ‘control’ to management (agent). This relationship between principal and agent is characterized through asymmetric information. Management, as organizational insider, has a better understanding and in-depth knowledge than the owners as organizational outsiders (Ruud 2003, p. 82).

- 32.

Because governance explicitly includes external parties such as shareholders and stakeholders but also mentions all means of attaining the organizational objectives (which represents internal control), the argumentation here is that governance is broader defined than internal control. Effective internal control can be understood as contributing to effective organizational governance.

- 33.

OECD (2004, p. 11).

- 34.

While the illustrated structure of the value chain of a manufacturing company represents only one possible example, each individual company has its own definition of the value chain. Internal control is pervasive throughout any organization’s primary and secondary activities and is inherently affected by the way management runs the business (Pfaff and Ruud, 2007, p. 21; Ruud, 2003, p. 78).

- 35.

CoCo (1995b, p. 6).

- 36.

CoCo (1995a, p. 7).

- 37.

Although internal control has a fundamental role for any business, in the literature relatively little attention is spent on integrating internal control with strategic control and management control (exceptions are Kinney 2000a; Merchant and Otley 2007; Simons 2000).

- 38.

Kinney’s figure illustrates ‘workers’ outside the firm, which can be debated from COSO’s perspective. In the COSO definition, ‘personnel’ are the one that effect internal control and are therefore part of the firm. Assuming that the term ‘workers’ represents the private person providing an economic exchange in form of workforce against payroll, this illustration sees workers outside the firm.

- 39.

CoCo (1995b, p. 11).

- 40.

Ulrich (2001, p. 250).

- 41.

Kinney (2000b, p. 85).

- 42.

COSO (1992, p. 6). Sunder (1997, p. 56) emphasizes that management depends on the information people share within the organization. It is the people’s own decision which information they are willing to share and how accurately and truthfully they share it.

- 43.

Ulrich (2001, p. 249).

- 44.

COSO (1992, p. 62).

- 45.

COSO (1992, p. 87) and Kinney (2000b, p. 84).

- 46.

Simons (1995, p. 5).

- 47.

For example, Simons (2000).

- 48.

Similar to the internal control literature, the management control literature traditionally focused on accounting information and often separated from operational and strategic control. However, recent developments in the management control literature recognize that such a focus neglects impacts on management control from strategy and operations. Otley (1999, p. 364) remarks: “Although it may well have been sensible to concentrate initially on the core area of ‘management control’, it is now necessary to pay more attention to the neglected elements of strategy and operations”.

- 49.

CoCo (1995b, p. 11). Internal control supports the achievement of organizational objectives. Therefore it is not an end in itself, but a means to an end (Pfaff and Ruud 2007, p. 22).

- 50.

Emphasis added.

- 51.

Ruud (2003, p. 75).

- 52.

An alternative definition provides Otley (1999, p. 364) who states that management control systems “provide information that is intended to be useful to managers in performing their jobs and to assist organizations in developing and maintaining viable patterns of behavior”. This view from Otley on management control integrates internal control and gives little room for making a distinction between internal control and management control.

- 53.

Simons (1990, p. 135).

- 54.

Simons (1990, p. 130).

- 55.

Merchant and Van der Stede (2007, p. 7).

- 56.

See Kaplan and Norton (1992).

- 57.

COSO (1992, p. 20).

- 58.

Ibid.

- 59.

Ibid.

- 60.

Kinney (2000a, p. 33, 62).

- 61.

See CoCo (1995b) and COSO (1992).

- 62.

Kinney (2000a, p. 33, 62).

- 63.

Kinney (2000b, p. 84).

- 64.

CoCo (1995b, p. 1). See also Ruud and Sommer (2006).

- 65.

CoCo (1995b, p. 2).

- 66.

Information from financial reporting contains, for example, earning and financial condition measures, periodic disclosures of off-balance items, such as certain types of leases, and transactions with parties related to management or the organization itself (Kinney 2000a, p. 37).

- 67.

Kinney (2000a, p. 37).

- 68.

CoCo (1995b, p. 1). Reliability is understood as central aspect towards the outside. Other aspects, such as giving the organization direction and assurance, which is important for shareholders and other groups, are considered part of reliability here.

- 69.

These aspects are discussed in regard to Sarbanes-Oxley requirements (for example, Rittenberg and Miller 2005; Zang 2005), but also in regard to more general organizational design (for example, Burton et al. 2006; Simons 2005).

- 70.

See also the Sarbanes-Oxley debate: Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. (2007), Coates (2007), Doyle et al. (2007), Ge and McVay (2005), Leone (2007), Rittenberg and Miller (2005), Ruud and Pfister (2006), and Zang (2005).

- 71.

See Rittenberg and Miller (2005).

- 72.

See Simons (2005).

- 73.

The term ‘effective internal control’ can also be used more specifically. For instance, it can stand for operations that are effective (but not necessarily efficient) or the term can be used to explain financial controls are reliable (e.g., in Sarbanes-Oxley context).

- 74.

This definition of material weaknesses in internal control is adapted from the definition of PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 5, which defines a material weakness as “a deficiency, or a combination of deficiencies, in internal control over financial reporting, such that there is a reasonable possibility that a material misstatement of the company’s annual or interim financial statements will not be prevented or detected on a timely basis” (PCAOB 2007, p. 43).

- 75.

PCAOB (2007, p. 41; emphasis added).

- 76.

PCAOB (2007, p. 41; emphasis added).

- 77.

COSO (1992, p. 15); Pfaff and Ruud (2007, p. 23).

- 78.

For example, CoCo (1995b, 2006b) and COSO (1992, 2004, 2006).

- 79.

COSO (1992, p. 80).

- 80.

CoCo (1995b, p. 3).

- 81.

COSO (1992, p. 80) describes many other reasons that cause top management or division managers to override controls. For example, they want “to increase reported revenue, to cover an unanticipated decrease in market share, to enhance reported earnings to meet unrealistic budgets, to boost the market value of the entity prior to a public offering sale, to meet sales or earnings projections to bolster bonus pay-outs tied to performance, to appear to cover violations of debt covenants or debt covenant agreements, or to hide lack of compliance with legal requirements. Override practices include deliberate misrepresentations to bankers, lawyers, accountants, and vendors, and intentionally issuing false documents such as purchase orders and sales invoices”. Management override is a typical aspect which demonstrates the overlap between internal control and management control.

- 82.

See Pfaff and Ruud (2007).

- 83.

Kinney (2000b, p. 84).

- 84.

COSO (1992, p. 79).

- 85.

Kinney (2000a, p. 91).

- 86.

CoCo (1995b, p. 3, 20).

- 87.

Krishnan (2005, p. 652).

- 88.

Of particular importance for these cost-benefit discussions are mandatory regulatory requirements. Regulatory requirements for internal control (e.g., Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404) set minimum standards for how an organization must formalize its internal control and therefore impact the cost-benefit trade-off within organizations. The more these formal regulatory requirements are prescribed, the higher the minimum costs for internal control will be. As a consequence, regulation can have an important impact on internal control design and raise competitive disadvantages for organizations that would be able to design and executive effective controls also in a more informal manner than law requires.

- 89.

For example, Dent (1991) and Hopwood (1978, 1983).

- 90.

See Collier (2005) and Simons (2005).

- 91.

Keyton (2005, p. 18).

- 92.

Harris (1990, p. 741).

- 93.

See Mintzberg (1979) and Thompson (1967).

- 94.

Perrow (1986, p. 725, 1991).

- 95.

Clegg (1981, p. 545).

- 96.

For studies investigating culture and performance see Kotter and Heskett (1992), Siehl and Martin (1990), and Sørensen (2002).

- 97.

See www.microsoft.com and www.schwab.com.

- 98.

Schein (2004, p. 7).

- 99.

See Keyton (2005).

- 100.

In order to meet the focus of this study, this subchapter focuses on defining organizational culture and does not discuss specific aspects such as the influence of leadership on culture or the relation between culture and climate.

- 101.

Hofstede et al. (1990, p. 286).

- 102.

If not more clearly specified, in the proceeding of this study, the terms ‘culture’, ‘corporate culture’ and ‘organizational culture’ are all used to explain the cultural phenomena related to an organization.

- 103.

Schein’s original figure was shortened. Also, authors that refer to the specific definitions were removed here.

- 104.

Although the focus here is on the organization, the concept of culture of any other instance is true for the specific culture of an organization as well. Therefore any definition of culture (whether referring to the organization or another reference) is included in this overview.

- 105.

See Keyton (2005).

- 106.

See Sect. 3.2.2.

- 107.

Alvesson (2002, p. 6).

- 108.

Bromann and Piwinger (1992) view culture in a timeframe and divide into what the cultural reality is, and what the desired status of the culture should be. They also argue that older organizations do not necessarily have “more culture”. Often in young companies team spirit and entrepreneurial thinking can bring culture more clearly to the forefront than in an established company.

- 109.

Taking a dynamic view, Schein (1990, p. 111) defines organizational culture as “a pattern of basic assumptions that a group has invented, discovered or developed in learning to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, and that have worked well enough to be considered valid, and therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems”.

- 110.

Taking a static view, O’Reilly and Chatman’s (1996, p. 166) organizational culture is “a system of shared values defining what is important, and norms, defining appropriate attitudes and behaviors, that guide members’ attitudes and behaviors.”

- 111.

Lim (1995, p. 17) and Schein (1990, p. 111).

- 112.

Traditionally, the concept of culture has been analyzed in anthropology. According to Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952, p.181), culture “consists in patterned ways of thinking, feeling and reacting, acquired and transmitted mainly by symbols, constitute the distinctive achievements of human groups, including their embodiments in artifacts; the essential core of culture consists of traditional (i.e., historically derived and selected) ideas and especially their attached values” (emphasis added).

- 113.

Dent (1991, p. 709) writes that cultures “in organizations are not independent of their social context. They are interpenetrated by wider systems of thought, interacting with other organizations and social institutions, both importing and exporting values, beliefs and knowledge”.

- 114.

See Collins and Porras (1996) and Tichy (1982).

- 115.

Schein (1990, p. 111).

- 116.

O’Reilly and Chatman (1996, p. 166).

- 117.

Schein (2004, p. 8).

- 118.

Schein’s quote shows how close organizational culture and internal control are. The quote contains typical internal control matters such as discussed in the section on the benefits of internal control.

- 119.

Denison et al. (2006, p. 7).

- 120.

Schein (2004, p. 109).

- 121.

Meglino and Ravlin (1998, p. 357).

- 122.

Emphasis added.

- 123.

See Denison et al. (2006) and Meglino and Ravlin (1998, p. 7)

- 124.

Wiener (1988, p. 534).

- 125.

There are some scholars that deny this influence of values on behavior and say that values only rarely influence behavior (for example, Kristiansen and Hotte 1989; McClelland 1985).

- 126.

D’Andrade (1984, p. 229) and Michela and Burke (2000).

- 127.

Values must be distinguished from other concepts such as opinions and attitudes. A value is more general and less bound to any specific object as opposed to many attitudes and opinions, which are situation-bound. Therefore a value can underlie numerous opinions and attitudes (Akaah and Lund 1994, p. 418; England 1967, p. 54).

- 128.

Rokeach (1973, p. 17).

- 129.

O’Reilly et al. (1991, p. 492).

- 130.

In accounting and control research social norms are often discussed in regard to incentive systems (for example, Kunz and Pfaff 2002).

- 131.

Michela and Burke (2000, p. 229).

- 132.

See D’Andrade (1984).

- 133.

Wiener (1988, p. 536).

- 134.

Meglino and Ravlin (1998, p. 356).

- 135.

Lim (1995, p. 17).

- 136.

See Hampdon-Turner (1990).

- 137.

While process-oriented approaches are often combined with theory-building and qualitative studies (see Alvesson 2002; Schein 2004), classification approaches often relate to quantitative studies in which culture is measured and related to specific organizational outcomes (see O’Reilly et al. 1991; Sarros et al. 2005; Sørensen 2002).

- 138.

Schein (2001, p. xxiv).

- 139.

These are common differentiations in interdisciplinary research.

- 140.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2009 Physica-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pfister, J. (2009). Basics. In: Managing Organizational Culture for Effective Internal Control. Contributions to Management Science. Physica, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7908-2340-0_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7908-2340-0_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Physica, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-7908-2339-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-7908-2340-0

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)