Abstract

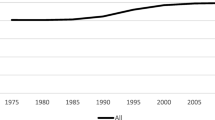

Since the mid-1970s, sub-Saharan candidates for migration to Europe have been confronted with increasingly stiff policy measures. This chapter explores how migration between Senegal and Europe has evolved in this context. Taking advantage of the retrospective nature of the data from the MAFE project (Migration between Africa and Europe) in addition to other available sources, it offers a unique quantitative account of the history of Senegalese migration. The results show that, between 1975 and 2008, there was neither a surge in out-migration (despite the widespread belief in an African invasion in Europe) nor the decline that might have been expected if restrictions had been effective. In fact, results tend in many ways to support the hypothesis that the effectiveness of restrictive policies is hampered by a number of unintended effects due to the ability of (would-be) migrants to adapt to new rules. Among these unintended effects are: the decline in intentions to return from Europe, the increase in attempts to migrate to Europe and the growth of irregular migration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Data sources of all statistics are presented below the figures and tables. All results are weighted. Readers should bear in mind that the samples used in the analyses vary from one table or graph to another, which can substantially affect the results interpretation. For more information see Chap. 2, which provides all details on MAFE samples.

- 2.

- 3.

In 1919, the French Minister for Agriculture and Supplies suggested recruiting migrant workers from the colonies (declaration of the Minister for Agriculture and Supplies, Journal Officiel, parliamentary debates, 29 January 1919).

- 4.

Italy regularized 217,000 migrants in 1998, 650,000 in 2002 and 350,000 in 2006; Spain regularized 200,000 migrants in 2000, 230,000 in 2001 and 580,000 in 2005. Note that Sub-Saharans were a small minority among the regularized migrants: in Italy, 14% in 1998 and 5% in 2002; in Spain, 14% in 2000 and 6% in 2001. France regularized 80,000 migrants in 1997–1998 and 7000 migrants in 2006, in addition to 122,000 migrants who were regularized through a case-by-case procedure between 1999 and 2006. Sub-Saharan migrants represented 40% of those regularized in France in 1997–1998 and 31% in 1999–2006. Sources: Lessault and Beauchemin (2009) and Kraler (2009).

- 5.

Note that the migration trends (departure and return) presented in this chapter are somewhat different from those presented in Flahaux et al. (2013), who used a different computation method. For a presentation of the method used in this book, see Chap. 3. And for a deeper methodological discussion of trend computation using retrospective data, see Schoumaker and Beauchemin (2014).

- 6.

For a discussion on the potential effects of distance on migration determinants, see Gonzalez-Ferrer et al. (2014).

- 7.

Results on the determinants of return point in the same direction as they show that undocumented Senegalese migrants are not more likely to return that those living in Europe with proper documents (see Chap. 4).

- 8.

However, it has been established that return to Senegal is a significant phenomenon. According to the Push-Pull data (1997–1998), more than a quarter of the households surveyed in the capital city (27%) contained at least one returnee. These returnees may be involved in circular migration: barely 50% of them declared that they had return for good, and more returnees than non-migrants declare an intention to move abroad (Robin et al. 1999). Furthermore, 30% of migrants living abroad were reported (by the interviewed household heads) to intend to return, this figure being higher among the more recent migrants and among those currently in Italy (compared to those in France or in Senegal’s neighboring countries, no results being available for Spain). In addition, 16% were said to be indecisive whether to come back or stay abroad. These figures are not representative of the Dakar region, but they illustrate quite well that return migration was a significant phenomenon at the end of the 1990s in the capital city.

- 9.

This exposure also results from migrants’ investments in the city. Tall (2008) suggests that massive (and thus visible) investments in real estate by migrants located in Europe contributed to the creation of a “culture of migration” that has increased emigration pressures.

- 10.

According to the 2002 Census, 19% of the recent migrants who left Dakar had gone to study, this proportion being only 10% at the national level (Baizan et al. 2013).

- 11.

- 12.

In line with the view that reunification did not become a major channel of entry among Senegalese migrants, Toma and Vause (2013) have shown that the likelihood of female migration increased very moderately over time.

- 13.

Note that this type of pioneer migration is largely but not exclusively a male experience: 41% of male migrants in Europe declared they knew nobody, against 20% among women (Table 13.6). For a discussion of the autonomy of female migration, see Toma and Vause (2013). Migrants with primary education or none at all are also more likely to be pioneers (i.e. to know nobody at destination) than those who are more educated (43% against 29%), the latter relying more on kinship (siblings: 26% against 17%; other kin: 22% against 15%).

- 14.

- 15.

As in many other contexts, family migration is a strongly gendered phenomenon: among the Senegalese interviewed in Europe, 42% of women declared family as a motive for migration, while the proportion was only 6% among men (Table 13.7).

- 16.

This type of migration is also highly gendered: 19% of female migrants in Europe travelled with a child or children, compared to 0% of male migrants (Table 13.8).

- 17.

These percentages were computed for the whole 1975–2007 period and so also reflect the migration routes observed in the more recent period (2000–2007), when Spain and Italy became more significant destinations of Senegalese migrants.

- 18.

These fears were notably expressed during the preparation of the European Pact on Immigration and Asylum (2008).

- 19.

On regularization numbers, see note 4.

- 20.

Because of the way the samples were constructed, migrants who were in transit countries (for instance in Morocco) at the time of the survey are absent from the biographic MAFE survey. The Senegalese sample may include returnees who have failed in their journey to Europe (e.g. migrants who went to Morocco, stayed there, were unable to cross the sea and finally returned to Senegal). Numbers are likely to be tiny. These cases could however be investigated in future research.

- 21.

The need to obtain a permit to leave the country was abolished only in 1981.

- 22.

Trends have been computed using different sources. Figure 13.1 (actual migration) is based on a sub-sample of the household data (children of households heads in Dakar), whereas Figure 13.5 (steps to migration) is based on the biographic data collected among all individuals in Dakar. As they refer to the same periods, the same place (Dakar) and the same destinations, we believe that a comparison between these trends is acceptable.

- 23.

This figure only concerns those who were actually able to immigrate to Spain: those who were apprehended and whose entry was refused are not counted here. Numbers of aliens refused in European countries (aggregates of all origin groups) can be consulted online in the MAFE Contextual Database.

- 24.

Plane was especially predominant among women: 97% of them used a plane, against 81% among men (all countries and periods combined). By contrast, the use of pirogues or pateras is almost exclusive to male migrants (10% against 1% for women). Means of transport also vary by education, with the more educated (secondary or higher education) being more likely to use a plane (94% against 75% for those with primary education or none at all) and less likely to use a pirogue or patera (1% against 16%).

- 25.

For further explanation of the institutional conditions explaining this type of change in administrative status, see Vickstrom (2014).

- 26.

In the rest of this section “irregular migrant”, “irregularity” etc. should be taken to refer to those whose status had been irregular status at some point during their first year in the destination country.

- 27.

On average, 30% of Senegalese migrants in France, Italy and Spain were “irregular”, with higher proportions among men (37% against 12% among women) and the less educated (38% among those with primary education or less, against 24% for those with higher education).

References

Amin, S. (1974). Modern migrations in Western Africa. London: Published for the International African Institute by Oxford University Press.

Ba, C. O. (1997). Réseaux migratoires des sénégalais du Cameroun et du Gabon en crise. In L. C. J. Bonnemaison & L. Quinty Bourgeois (Eds.), Le territoire, lien ou frontière ? Identités, confits ethniques, enjeux et recompositions territoriales. Paris: ORSTOM.

Ba C. O., & Ndiaye, A. I. (2008). L’émigration clandestine Senegalese, Revue Asylon(s), N°3, mars 2008, Migrations et Senegal., url de référence. http://www.reseau-terra.eu/article717.html

Baizán, P., Beauchemin, C., & González-Ferrer, A. (2013). Determinants of migration between Senegal and France, Italy And Spain (MAFE Working Paper). Paris: INED: 38.

Baizán, P., Beauchemin, C., & González-Ferrer, A. (2014). An origin and destination perspective on family reunification: The case of Senegalese couples. European Journal of Population, 30(1), 65–87.

Barou, J. (1993). Les immigrations africaines en France: des “navigateurs” au regroupement familial. Revue Française des Affaires Sociales, 1, 193–205.

Bava, S. (2003). De la baraka aux affaires: ethos économico-religieux et transnationalité chez les Senegalese migrants mourides. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales, 19(2), 69–84.

Beauchemin, C. (2014). A manifesto for quantitative multi-sited approaches to international migration. International Migration Review, 48(4), 921–938.

Beauchemin, C., et al. (2014). Reunifying versus living apart together across borders: A comparative analysis of sub-Saharan migration to Europe. International Migration Review, 49, 173–199.

Bertoncello, B., & Bredeloup, S. (2004). Colporteurs africains à Marseille: un siècle d’aventures. Paris: Autrement.

Blion, R., & Bredeloup, S. (1997). La Côte d’Ivoire dans les stratégies migratoires des Burkinabè et des Sénégalais. In H. Memel-Foté & B. Contamin (Eds.), Le modèle ivoirien en questions: Crises, ajustements, recompositions (pp. 707–738). Paris: ORSTOM-Karthala.

Boyd, M. (1989). Family and personal networks in international migration: Recent developments and new agendas. International Migration Review, 23(3), 638–670.

Bredeloup, S. (2007). La diams’pora du fleuve Sénégal: sociologie des migrations africaines. Toulouse-Paris, Presses universitaires du Mirail; IRD éditions, Institut de recherche pour le développement.

Bredeloup, S., & Pliez, O. (2005). Migrations entre les deux rives du Sahara. Autrepart, 36, 3–20.

Carling, J. (2007). Migration control and migrant fatalities at the Spanish-African borders. International Migration Review, 41(2), 316–343.

Castagnone, E. (2010). Building a comprehensive framework of African migratin patterns: The case of migration between Senegal and Europe. Tesi di dottorato di recerca, Universita degli studi di Milano.

Castagnone, E. (2011). Transit migration: A piece of the complex mobility puzzle. The case of Senegalese migration. Cahiers de l’Urmis 13.

Cordell, D. D., Gregory, J. W., & Piché, V. (1996). Hoe and Wage: A social history of a circular migration system in West Africa. Boulder: Westview Press.

de Haas, H. (2008). The myth of invasion: Irregular migration from West Africa to the Maghreb and the European Union. Third World Quarterly, 29(7), 1305–1322.

de Haas, H. (2011). The determinants of international migration: Conceptualising policy, origin and destination effects (DEMIG Project Paper n°2). Oxford: Oxford University – International Migration Institute (IMI): 35.

Duruflé, G. (1988). L’ajustement structurel en Afrique (Sénégal, Côte d’Ivoire, Madagascar). Paris: Karthala.

Ebin, V. (1993). Les commerçants mourides à Marseille et à New York. Regards sur les stratégies d’implantation ». In E. Grégoire et P. Labazée (Eds.), Grands commerçants d’Africa de l’Ouest. Logiques et pratiques d’un groupe d’hommes d’affaires contemporains (pp. 101–123). Paris: Karthala-Orstom.

Fall. (2005, March). Le Destin Des Africains Noirs En France: Discriminations, Assimilation, Repli Communautaire. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Flahaux, M.-L. (2014). The influence of migration policies in Europe on return migration to Senegal (IMI Working Paper 93).

Flahaux, M.-L. (2015). Migration de retour au Sénégal et en RD Congo: Intention et réalisation. Population [Also availaible in English in the English version of Population] (forthcoming).

Flahaux, M.-L., Beauchemin, C., & Schoumaker, B. (2013). Partir, revenir: un tableau des tendances migratoires congolaises et sénégalaises. In C. Beauchemin, L. Kabbanji, P. Sakho, & B. Schoumaker (Eds.), Migrations africaines: le co-développement en questions. Essai de démographie politique (pp. 91–126). Paris: Armand Colin.

Flahaux, M.-L., Beauchemin, C., & Schoumaker, B. (2014). From Europe to Africa: Return migration to Senegal and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Population and Societes, 515(4).

Gabrielli, L. (2011). La construction de la politique d’immigration espagnole: Ambiguités et ambivalences à travers le cas des migrations ouest-africaines. Thèse pour le Doctorat en Science politique, Université de Bordeaux.

González-Ferrer, A., Baizán, P., & Beauchemin, C. (2012). Child-parent separations among Senegalese migrants to Europe: Migration strategies or cultural arrangements? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 643(1), 106–133.

Gonzalez-Ferrer, A., et al. (2014). Distance, transnational arrangements and return decisions of Senegalese, Ghanaians and Congolese migrants. International Migration Review, 48(4), 939–971.

Guilmoto, C. (1998). Institutions and migrations. Short term versus long term moves in Rural West Africa. Population Studies, 52, 85–103.

Kaag, M. (2008). Mouride transnational livelihoods at the margins of a European society: The case of residence Prealpino, Brescia, Italy. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies, 34(2), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830701823848.

Kraler, A. (2009). Regularisation: A misguided option or part and parcel of a comprehensive policy response to irregular migration? (IMISCOE Working Paper 24).

Lessault, D., & Beauchemin, C. (2009). Ni invasion, ni exode: Regards statistiques sur les migrations d’Afrique subsaharienne. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales, 25(1), 163–194.

Lessault, D., & Flahaux, M.-L. (2014). Regards statistiques sur l’histoire de l’émigration internationale au Sénégal. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales, 29(4), 59–88.

Liu, M. M. (2013). Migrant networks and international migration. Testing weak ties. Demography, 50, 1243–1277.

Manchuelle, F. O. (1997). Willing migrants: Soninke labour diasporas, 1848–1960. Athens/London: Ohio University Press/James Currey Publishers.

Massey, D., & Espinosa, K. (1997). What’s driving Mexico-US migration? A theroritical, empirical, and policy analysis. The American Journal of Sociology, 102(4), 939–999.

Massey, D., et al. (2001). Social capital and international migration: A test using information on family networks. The American Journal of Sociology, 106(5), 1262–1298.

Massey, D., Durand, J., & Malone, N. (2002). Beyond smoke and mirrors: Mexican immigration in the area of economic integration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Mezger, C. L. (2012). Essays on migration between Senegal and Europe: Migration attempts, investment at origin and returnees’ occupational status. Ph.D. University of Sussex.

Mezger, C., & Gonzalez-Ferrer, A. (2013). The ImPol data-base: A new tool to measure immigration policies in France, Italy and Spain since the 1960s (MAFE Working Paper). Paris: INED: 43.

Riccio, B. (2005). Talkin’ about migration. Some ethnographic notes on the ambivalent representation of migrants in contemporary Senegal. STICHPROBEN. Wiener Zeitschrift fr kritische Afrikastudien, 8, 99–118.

Robin, N., Lalou, R., & Ndiaye, M. (1999). Facteurs d’attraction et de répulsion à l’origine des flux migratoires internationaux. Rapport national Sénégal (p. 173). Dakar/Bruxelles: IRD/Commission européenne, Eurostat.

Sakho, P. (2005). Marginalisation et enclavement en Afrique de l’Ouest: « l’espace des trois frontières » sénégalais. Espace, Populations, Sociétés, 2005-1, 163–168.

Sarr, F., et al. (2010). Migration, transferts et développement local sensible au genre. Le cas du Senegal, UN INSTRAW (p. 60). Dakar: UNDP.

Schoumaker, B., & Beauchemin, C. (2014). Reconstructing trends in international migration with three questions in household surveys (MAFE Working Paper). Paris: INED: 26.

Sinatti, G. (2009). Home is where the heart abides. Migration, return and housing in Dakar, Senegal open house international, special issue. Home, Migration, and The City: Spatial Forms and Practices in a Globalising World, 34(3), 49–56.

Tall, S. M. (2002). L’émigration internationale sénégalaise d’hier à demain. In Momar-Coumba Diop (Ed.), La société sénégalaise entre le local et le global (pp. 549–577). Paris: Karthala.

Tall, S. M. (2007). Les migrants sénégalais en Italie: espace, territoires et translocalité. In Jean-Luc Piermay et Cheikh Sarr (Eds.), La ville Sénégalaise. Une invention aux frontières du monde. Paris. Hommes et sociétés. Karthala, 246p.

Tall, S. M. (2008). La Migration International Sénégalaise: Des Recrutements de Main-D’oeuvre Aux Pirogues. In Momar-Coumba Diop (Ed.), Le Sénégal Des Migrations: Mobilités, Identités Et Sociétés, edited by Momar-Coumba Diop (pp. 37–67. Hommes et Sociétés). Paris: Karthala.

Tall, S. M., et Tandian, A. (2011). Cadre général de la migration internationale Senegalese: historicité, actualité et prospective, Carim SA 2011/54. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, San Dominici Di Fiesole, Institut Universitaire Européen.

Tandian, A. (2008). Des migrants sénégalais qualifiés en Italie: entre regrets et résignation. In Momar-Coumba Diop (Ed.), Le Sénégal des migrations: Mobilits, identités et sociétés (pp. 365–388). Paris: KARTHALA, ONU-Habitat et CREPOS.

Thomas, K. J. A. (2011). What explains the increasing trend in African emigration to the U.S.? International Migration Review, 45(1), 1747–7379.

Toma, S., & Vause, S. (2013). On their own? A study of independent versus partner-related migration from the democratic republic of Congo and Senegal. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 34(5), 533–552.

Toma, S., & Vause, S. (2014). Gender differences in the role of migrant networks: Comparing congolese and senegalese migration flows. International Migration Review, 48, 972–997. Article first published online: 11 Nov. 2014.

Triandafyllidou, A. (Ed.). (2010). Irregular migration in Europe: Myths and realities. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Vickstrom, E. (2013). The production and consequences of irregularity in multiple contexts of reception: Complex trajectories of legal status of senegalese migrants in Europe. Ph.D. thesis, Princeton University.

Vickstrom, E. (2014). Pathways into irregular status among senegalese migrants in Europe. International Migration Review, 48(4), 1062–1099.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Beauchemin, C., Sakho, P., Schoumaker, B., Flahaux, ML. (2018). From Senegal and Back (1975–2008): Migration Trends and Routes of Migrants in Times of Restrictions. In: Beauchemin, C. (eds) Migration between Africa and Europe. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69569-3_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69569-3_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-69568-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-69569-3

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)