Abstract

The reproduction of the corporation and its legal person status has become something of a self-reinforcing tendency. The law accepts and works with the ambiguity and contradictions of a non-conscious immaterial entity that has legal person status. It does so in order to manage difference. There is, however, a difference between managing difference and preventing increasing disintegration of a system over time. The problem of disintegration creates issues regarding how one addresses specific problems of growing corporate power. Tax avoidance is one important area to address. Corporate tax avoidance is antithetical to human flourishing and also part of a system of human harm. As such, addressing tax avoidance has significance for any concept of Eudaimonia and the Morphogenic Society.

A posse ad esse: from possibility to actuality.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution.

Buying options

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Learn about institutional subscriptionsNotes

- 1.

One might also note the ability to demand the enforcement of contract law as a primary right acquired by the corporation as a legal person.

- 2.

‘Seems necessary’ is an operative term, since the role of ideas raises issues of false necessity, discussed for example by Heikki Patomäki in terms of corporate power and more generally by Roy Bhaskar in terms of TINA formations.

- 3.

Specifically, Section 906 states that the CEO and CFO are required to sign off quarterly financial reports, and in so doing they confirm that those accounts ‘fairly represent’ the material financial condition of the corporation. If they sign ‘knowing’ this is not the case they face fines of $1 m to $5 m and imprisonment for up to 10 years or up to 20 years, depending on the specific nature of the offence (executives can also have pay clawed back in later years for related offences).

- 4.

In Dodd-Frank, three key issues were the elimination of moral hazard (perceived incentives to take reckless decisions because the gains can be immediate, and the possible detrimental effects are either long term, uncertain or will be likely suffered or covered by others), the strengthening of internal ‘risk’ management procedures, and limitations on certain kinds of activities (notably on direct ownership of hedge funds and private equity firms in what is termed the ‘Volcker Rule’, see Morgan and Sheehan 2015). In 2014/15 the PRA proposed a ‘guilty until proved innocent’ rule for senior bankers. If and when the organization for which they act manifests problems that may be indicative of some form of reckless behaviour or malfeasance then executives would be subject to a reverse burden of proof. That is, they would have to demonstrate they had sought to prevent the consequences - the assumption being this would foster a greater focus on creating and monitoring the formal systems within the organization, as well as its internal ‘culture’, since the latter may otherwise undermine the former.

- 5.

According to Drutman, corporations report spending approximately $2.6 billion per year on lobbying the US Congress and Senate, which is more than both houses actually cost to run; corporations spend around $34 on lobbying for every $1 spent by other forms of organization (unions, civil society groups etc) and 95 of the top 100 lobby groups are corporations or their industry representatives. Katz (2015) also makes the case that corporate lobbying has increasingly captured democratic spaces in the US to the detriment of other interest groups (notably labour). The EU has a transparency register for organizations seeking to influence EU bodies, but registration is not mandatory. As of December 2015 the register had 8981 registrant organizations. According to the campaign-working group, Corporate Europe Observatory, there are at least 30,000 lobbyists working in Brussels (compared to 31,000 EU staff), and there is a widespread problem of revolving door employment of MEPs, with large corporations, and many corporate interests, dominating consulting and advisory committees for EU policy. Patronage and influence also works on a personal level. For example, The Sunday Times published a supplement ‘Power, Politics, Money and Influence: The Political Rich List,’ April 19th 2015. It identified 197 people who had appeared on its general Times Rich List who were also significant political donors. These 197 contributed £82.4 m to the three main political parties (the majority to the Conservatives) between 2011 and 2015, and this constituted approximately half of the total donations of £174.7 m donated over that period. Seven of the top 10 donors were ennobled, knighted or received a CBE. Notable multi-million donors include Lord Farmer, founder of the RK Management hedge fund (made senior treasurer of the Conservatives); Sir Michael Hintze, founder of the hedge fund CQS, and Michael Spencer, CEO of ICAP.

- 6.

Section 906 of the Act is problematic, since ‘knowingly’ creates a standard of evidence that is difficult to establish. Only particularly egregious cases are prosecuted. Concomitantly, as of 2015 there have been fewer than 50 cases where the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has sought to claw back pay from executives, and the first case was only brought in 2007. Section 404 of the Act (which requires auditors to give an opinion on internal financial control mechanisms - something which may later create a source of evidence) has never been fully implemented (having been consistently delayed by the SEC).

- 7.

Much as Sarbanes-Oxley is affected by ‘knowingly’.

- 8.

Rather than a ‘presumption’ (where one must establish one sought to prevent adverse consequences) there is now a general ‘duty’ of responsibility for the organization’s conduct. In real terms this is little different from previously - since it is inherent in the role of senior executive that one is acting on behalf of the corporation. One might also note that the annual bank levy was reduced by then Chancellor George Osborne, and ring-fencing of investment bank components has been scaled back; and one might note that during the same period Stuart Gulliver CEO of HSBC has been engaged in a review regarding shifting its base of operations to Hong Kong (a two year review process creates some scepticism regarding the real purpose of this review - would it make sense to shift one’s headquarters to a place where China would have significant influence? And what information could still be outstanding after 2 years?).

- 9.

Implying also that the state has been to some degree captured by the concerns of corporations and so the two become more aligned - a key claim made on behalf of neoliberalism and governance.

- 10.

This might also be considered in terms of versions of corporate manslaughter. Here the corporation can be convicted of the crime that its activity (or failures to act) leads to a person’s death. The criminal standard applied differs from civil litigation. A financial penalty is applied to the corporation, but the ultimate threat of imprisonment is directed at key executives; few countries have a version of this law. It does, however, exist in the UK as the Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act, 2007. The test applied in the UK is management failure (a breach in a management system akin to gross negligence). The concept of corporate manslaughter has been criticised as expensive (punishing innocent shareholders), unnecessary (given the existence of civil litigation) and senseless - given the corporation lacks sentience and will not be held accountable in any real sense beyond the pecuniary (For underlying issues see Coffee 1981; also, Wells 2001: Chps, 4 & 6; for more adversarial critique see Tombs and Whyte 2015).

- 11.

For example: ‘“Saint” Antony Jenkins was brought in to clean up Barclays as chief executive after the Libor scandal, but profits suffered. He was cleared out and is being replaced with Jes Staley, an investment banker on a £10 million package. The lesson: ethics and profits don’t mix.’ (Aldrick 2015)

- 12.

Though phrased in terms of shareholder value the point is actually more general. The same pressures occur in terms of private equity finance, where the private equity firms create an investment fund run by a general partner (from the firm) on behalf of passive investors (termed limited partners), the fund is then used in conjunction with debt to buy companies (originally public or private, but turned into private companies for some duration - these are termed acquisitions). See Morgan 2009. Note also, one should not conflate the concept of the firm or recognizable entity with the corporation per se - since the corporation is a legal structure which may be constructed precisely to disaggregate the firm into many corporations.

- 13.

For critique of the empty rhetoric of much of CSR see Porter and Kramer 2006, and 2011. For the growing extent of CSR projects, agendas and mission statements among corporations see the periodic KPMG survey. For example, 93 % of the world’s 250 largest corporations reported on CSR in 2013, compared to 80 % in 2008 (KPMG 2013: p. 10).

- 14.

Noting also that technology is not fate - it is not deterministic but used and developed within social relations that give meaning and purpose to technology. Moreover, if one takes a Kondratieff wave approach to the diffusion of fundamental technologies, and the way societies reconstruct around them, and then consider past instances (the steam engine, electricity, chemicals, transistors, microchips etc.) this has taken decades to occur, so even if one accepts that the digital revolution is a fundamental change - it may well be too early to have a clear sense of what its fuller impacts will be (despite there already being clear consequences). One might also note that a focus on the digital may neglect the other major sources of technological change currently occurring (notably hydrogen batteries, new varieties of solar panels, nano-technology and synthetics - graphene etc.). See also Lawson 2014: 34–44, for link to systems and corporations.

- 15.

Note the term tax haven should be used advisedly - any state can be a tax haven from the point of view of another; moreover, the generic use of the term tends to give the impression that only a particular and limited set of localities are problematic as havens (e.g. the Cayman Isles or some of the Swiss cantons). However, these are destinations, what matters are the processes, and there are many other expediting localities - not least the main financial centres, such as the City of London.

- 16.

The figures include all corporations and so also include those that are effectively domestic firms only (as organizations), which are unable to use the same strategies. Moreover, since many havens do not report (though this is changing) accounts and corporations are able to manipulate their accounts - it is difficult to provide a definitive assessment of what is avoided. This is one reason why country-by-country reporting will be a major (if limited in some ways) policy change; as is the growing pressure on havens (led notably by the US) to improve their transparency.

- 17.

However, the argument here is conditional on how one conceives the state and money creation.

- 18.

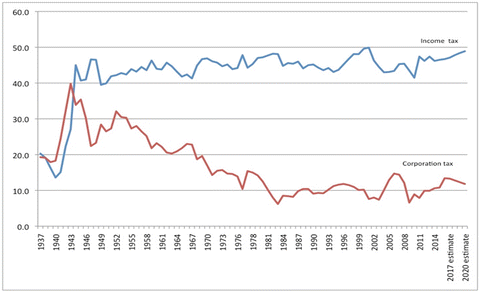

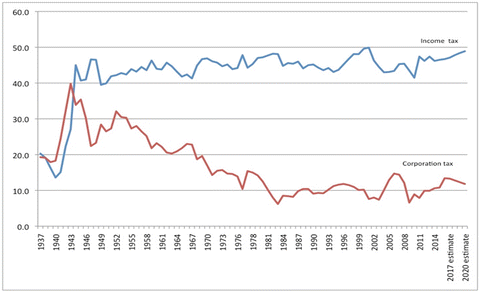

For comparison note how corporation tax as a % of total tax receipts in the US has declined over the last century, whilst income tax has not:

Source, Table 1: http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Historicals/

- 19.

More specifically, Murphy argues that tax plays many key roles in a modern society, economy and polity. First and foremost, it gives citizens a sense they have a stake in society and the state (affecting legitimacy and consent, and affecting the degree of participation and sense of representation). Thereafter, it serves 5 other functions. Following modern monetary theory (and as the Bank of England now acknowledges), Murphy accepts that money creation is based on the state’s capacity to spend in an economy, and the banking system further creates money through lending, which in turn creates matching savings (so it is wrong to assume that it is tax that creates the capacity to spend, and it is wrong to assume that it is deposits, which create the capacity to lend; institutional contexts rather limit the nature of spending and lending). So, tax serves the economic functions of: 1. Reclaiming money the state has spent in the economy (rather than creating the basis on which the state spends); 2. Legitimates the state denominated medium of exchange (the currency used), since it is the form used to pay taxes; 3. Provides a means by which the state intervenes in the economy to affect the levels of activity; 4 Provides a means for the government to engage in distribution and redistribution of income and wealth; 5. Allows the state to re-price goods and services for social purposes (encouraging some forms of socio-economic activity and discouraging others - taxes on petrol, smoking etc).

- 20.

Though this has not meant it has been conceived as necessarily anti-capitalist, anti the corporation etc.

- 21.

It functions best as an international (regional) or global system.

- 22.

Digital goods include all forms of product that are information basic - software and electronic games, research, novels, media, music, film, social media, etc. A digital economy is one where digital goods are distributed or transmitted, and includes platforms which serve as means for other forms of goods and services to be exchanged.

- 23.

However, there is no reason why this must be flourishing for all, it may simply be flourishing for the few. Some are already exploring the way current tendencies are encouraging various powerful actors to plan preservation solutions that are intrinsically militaristic, authoritarian, conflict-based and isolationist (Buxton and Hayes 2016).

References

Aldrick, P. (2015). Business leaders must do their fair share to protect capitalism. The Times November 4th.

Allingham, M., & Sandmo, A. (1972). Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics, 1(3–4), 323–338.

Archer, M. S. (2012). The reflexive imperative in late modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Archer, M. S. (2013). Social morphogenesis and the prospects of morphogenic society. In M. Archer (Ed.), Social morphogenesis. Dordrecht: Springer.

Archer, M. S. (2014). The generative mechanism re-configuring late modernity. In M. Archer (Ed.), Late modernity. Dordrecht: Springer.

Archer, M. S. (2015). How agency is transformed in the course of social transformation: Don’t forget the double morphogenesis. In M. Archer (Ed.), Social morphogenesis: Generative mechanisms transforming late modernity. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bainbridge, S. (2012). Corporate governance after the financial crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bakan, J. (2005). The corporation (new ed.). London: Constable and Robinson.

Buxton, N., & Hayes, B. (Eds.). (2016). The secure and the dispossessed. London: Pluto Press.

Coffee Jr., J. (1981). “No soul to damn, no body to kick,”: An unscandalized inquiry into the problem of corporate punishment. Michigan Law Review, 79(3), 386–459.

Colledge, B., Morgan, J., & Tench, R. (2014). The concept(s) of trust in late modernity, the relevance of realist social theory. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 44(4), 481–503.

Corporate Reform Collective. (2014). Fighting corporate abuse: Beyond predatory capitalism. London: Pluto.

Drutman, L. (2015). The business of america is lobbying: How corporations became politicized and politics became more corporate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gillies, D. (2015). Paul mason’s postcapitalism. Real World Economics Review, 73, 110–119.

Gorski, P. (2015). Causal mechanisms: lessons from the life sciences. In M. Archer (Ed.), Social morphogenesis: Generative mechanisms transforming late modernity. London: Springer.

Haldane, A. (2015). ‘Who owns a company?’ Speech, University of Edinburgh Corporate Finance Conference, May 22nd; Bank of England Publications

Ireland, P. (1999). Company law and the myth of shareholder ownership. The Modern Law Review, 62(1), 32–57.

Katz, A. (2015). The influence machine: The US chamber of commerce and the corporate capture of american life. New York: Random House.

Kay, J. (2015). ‘Shareholders think they own a company – They are wrong,’ Financial Times November 10th.

KPMG. (2013). The KPMG Survey of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting 2013 KPMG; accessed 7th Dec 2015; available at: https://www.kpmg.com/Global/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/corporate-responsibility/Documents/corporate-responsibility-reporting-survey-2013-exec-summary.pdf

Lawson, T. (2014). ‘A speeding up of the rate of social change? Power, technology, resistance, globalization and the good society’ In M. Archer (Ed.), Late modernity. London: Springer.

Lawson, T. (2015). The modern corporation: The site of a mechanism (of global social control) that is out-of-control. In M. Archer (Ed.), Social morphogenesis: generative mechanisms transforming late modernity (pp. 206–230). London: Springer.

Lazonick, W. (2015). ‘Stock buybacks: From retain-and-reinvest to downsize-and-distribute,’ Center for Effective Public Management at Brookings, April; accessed 18th August, available at: http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2015/04/17-stock-buybacks-lazonick/lazonick.pdf

Luttmer, E., & Singhal, M. (2014). Tax morale. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(4), 149–168.

Morgan, J. (2009). Private equity finance: Rise and repercussions. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Morgan, J. (2015). Piketty’s calibration economics: Inequality and the dissolution of solutions? Globalizations, 12(5), 803–823.

Morgan, J. (2016a). Corporation tax as a problem of MNC organizational circuits: The case for unitary taxation. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18(2), 463–481.

Morgan, J. (2016b). Paris COP21: Power that speaks the truth? Globalizations, 13(6), 943–951.

Morgan, J., & Sheehan, B. (2015). Has reform of global finance been misconceived? Policy documents and the Volcker Rule. Globalizations, 12(5), 695–709.

Murphy, R. (2015). The Joy of tax: How a fair tax system can create a better society. London: Bantam.

Pagano, U. (2010). Legal persons: The evolution of fictitious species. Journal of Institutional Economics, 6(1), 117–124.

Palan, R. (2002). Tax havens and the commercialization of state sovereignty. International Organization, 56(1), 151–176.

Picciotto, S. (2011). Regulating global corporate capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Porter, M., & Kramer, M. (2006). Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78–92.

Porter, M., & Kramer, M. (2011). Creating shared value: How to reinvent capitalism – And unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review, 89(1/2), 62–77.

Robe, J. (2011). The legal structure of the firm. Accounting, Economics and Law, 1(1), 2–86.

Seabrooke, L., & Wigan, D. (2014). Global wealth chains in the international political economy. Review of International Political Economy, 21(1), 257–263.

Seabrooke, L., & Wigan, D. (2015). How activists use benchmarks: Reformist and revolutionary benchmarks for global economic justice. Review of International Studies, 41(5), 887–904.

Seabrooke, L. and Wigan, D. (2016) Powering ideas through expertise: Professionals in global tax battles Journal of European Public Policy, 23(3), 357–374.

Sharman, J. (2010). Offshore and the new international political economy. Review of International Political Economy, 17(1), 1–19.

Sikka, P. (2015). No accounting for tax avoidance. Political Quarterly, 86(3), 427–433.

Tench, R., Sun, W., & Jones, B. (Eds.). (2012). Corporate social irresponsibility volume 4: A challenging concept. Emerald: Bingley.

Tombs, S., & Whyte, D. (2015). The corporate criminal: Why corporations must be abolished. London: Routledge.

Veldman, J., & Willmott, H. (2013). What is the corporation and why does it matter? Management, 16(5), 605–620.

Wells, C. (2001). Corporations and criminal responsibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press, second edition.

Williams, K. (2000). From shareholder value to present-day capitalism. Ecology and Society, 29(1), 1–12.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Morgan, J., Sun, W. (2017). Corporations, Taxation and Responsibility: Practical and Onto-Analytical Issues for Morphogensis and Eudaimonia – A posse ad esse?. In: Archer, M. (eds) Morphogenesis and Human Flourishing. Social Morphogenesis. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49469-2_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49469-2_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-49468-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-49469-2

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)