Abstract

For better and worse, community resettlement as climate adaptation can disrupt regional land and property relations. Government officials in U.S. jurisdictions have raised concerns that resettlement threatens municipal budget stability by potentially decreasing the property tax base and stifling future development (Koslov in Public Culture 28:359–387, 2016; Shi and Varuzzo, Cities 100, 2020).

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

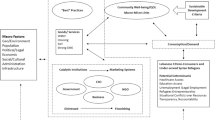

For better and worse, community resettlement as climate adaptation can disrupt regional land and property relations. Government officials in U.S. jurisdictions have raised concerns that resettlement threatens municipal budget stability by potentially decreasing the property tax base and stifling future development (Koslov, 2016; Shi & Varuzzo, 2020). Threats of ecological disaster can drive up housing and land costs in nearby, supposedly safer locations (Keenan & Bradt, 2020; Taylor & Aalbers, 2022). Finally, new displacements happen simultaneously, and wholly outside of climate risks, due to development, gentrification, the corporate consolidation of land and residential housing, and mass incarceration, among other forces. There is a lack of anti-displacement policies throughout the country (Anguelovski et al., 2019). These various dynamics can interact within the contexts of ecological disaster, amplifying demands for public investments in affordable and social housing (Fleming et al., 2019; Li & Spidalieri, 2021; Morris, 2021) as well as creating debate on the inequities and structural violence already baked into the housing market (De Vries & Fraser, 2012; Siders, 2018).

Efforts to link mobility and adaptation policy in the United States therefore evoke long-standing and urgent questions about the relationships between land as property, U.S. housing policies, and environmental and climate justice. In what ways do histories of uneven development, forced displacement, and racialized or gendered housing precarity come to bear on community and Tribal-driven resettlement processes and outcomes? How do property relations endure in the wake of climate disasters that seem to lay bare the unjust conditions produced, in part, by the U.S. property regime in the first place? In coastal Louisiana, policies intended to restore coastal environments and create resilience among coastal communities have habitually accommodated socio-environmental risk producers, like land speculators and the fossil fuel industries, who have both shaped and leveraged the U.S. property regime for profits. In this chapter, we consider the reconfiguration of property relations in the wake of the environmental catastrophe of coastal habitat loss as colonial, insofar as Black and Indigenous ecological and social relations are further fractured and industrial actors standing as stakeholders are sustained, despite the damage they have caused (Barra, 2021; Jessee, 2022).

Building on observations throughout one resettlement planning process in Louisiana, and taking seriously insights provided by climate migration and urban studies scholarship, this chapter considers the peril created by narrowly framed climate adaptation policy and planning. Given the historical scope of socio-environmental risks and the known effects of existing real estate practices and inadequate government protections, we explore how narratives of market value limited adaptation options produced by the state. Additionally, the chapter takes up several themes raised throughout the book, including, how the unjust existing property regime shapes human mobility in relation to environmental and climate change; divergent conceptualizations of community and how people are encouraged or discouraged to act communally; and interactions among the market, market actors, and law throughout displacement and resettlement.

Community Resettlement as a Real Estate Transaction

Privileging land as real estate and resettlement as a real estate transaction may undermine local climate adaptation. This was especially vivid as the state of Louisiana administered federal funds in a way that exploited Jean Charles Choctaw Nation leaders whose resettlement planning began in 2002, garnered state support in 2014, and was awarded federal funding in 2016. Prior to the funding, resettlement was envisioned by Tribal leaders as a struggle for cultural survival in the wake of multigenerational experiences of land grabs, ecological destruction caused by oil and gas extraction and river development, and forced displacement (Comardelle, 2020; Maldonado et al., 2021). As discussed further in Chapter 5, Tribal leaders prioritized the reunification of displaced Tribal citizens and rekindling traditional ways of life on higher ground. Among other initiatives, their plans included enhancing collective Tribal land stewardship both on the Island via continued ownership, occasional temporary habitation on the Island, new investments in ceremony, and tribal economic development activities at a new inland location via the establishment of a community land trust. Tribal leaders articulated these goals of collective land stewardship as an overall risk mitigation strategy with the understanding that individual households who moved would be safer from hurricanes and could be better supported by the Tribe if tax burdens increased, or insurance costs rose. The Tribe’s plans were used by Louisiana’s Office of Community Development to acquire $48.3 million through the federally sponsored National Disaster Resilience Competition, however, upon receiving the money, state officials imposed a different framework of resettlement that prioritized ongoing land commodification, and individualized household property ownership. During planning meetings and conversations, Louisiana’s lead resilience administrator working on the resettlement repeatedly emphasized, “At its core, the resettlement is essentially a very complicated real estate transaction.”

State planners articulated the real estate framework alongside their exploitation of Indigenous planning and as they reduced commitments to their partnership with Tribal leadership (Jessee, 2022). In 2018, Louisiana’s Office of Community Development began what local leaders experienced as a divisive planning process that undermined years of work by the Tribe. Simultaneously, the agency released eligibility requirements for those moving to the resettlement site. These requirements surprised Tribal leaders and departed from the initial resettlement goals. The guidelines provided multiple “options” for individual households depending on their relationship to the Island and financial capacity. Option A consisted of a parcel of land and new house in the resettlement site. Eligibility was limited to only those who lived on Isle de Jean Charles at the time of the grant allocation (2016) or those who had left since 2012—the regulatory “tie back date,” which is the year of the congressional appropriation of funds. That same demographic also could choose Option D, a house outside of the new location and outside the flood zone. Initially, the state tried to establish 40-year mortgages for Island properties, so that eventually property would be transferred to the state, but the Tribe resisted. After a mobilization against the state’s attempt to take Island property, the state used a contract to guarantee that families who resettled would not lose their Island property, at least as part of the resettlement. However, these homeowner contracts also created the risk of future loss of those properties if restrictions were not met. The agreements however are also pretty restrictive, prohibiting those who resettle from making substantial repairs to Island property if damaged in storms and prohibiting the use of Island property as fishing camps or rental properties, a limitation on use by which the white campers and few Indigenous households who did not apply for a new home in the resettlement do not have to abide.

Many Island residents, including some Tribal leaders who have led the resettlement effort, had been displaced or left the Island in the wake of storms or because of road flooding prior to 2012 and were therefore ineligible for either Option A or Option D. Some of this group was eligible instead for Option B, an empty lot in the new location, but no house. Eligibility for this option, however, was limited to those who could demonstrate the ability to finance the construction of a new house themselves and who would let go of any existing housing that they own due to the regulatory prohibition on public funding for second homes. The qualification to demonstrate financial capacity meant that low-income former Island residents could not meet this requirement and would thus be prevented from moving closer to friends, family, and other social networks that were relocating to the new site. Leaving out low-income households from the resettlement may also have meant that the Tribal members who could have most benefited from the resilience plans Tribal leaders had envisioned were left out of the new resettlement. The qualification to let go of existing homes deterred many other Tribal citizens and at least some Tribal leaders who argue they could have added organizing capacity to the new community. Option C allowed for the public auctioning of properties that do not get claimed through the planning stages with current and former Island residents. According to state documents, “Any unused lots in the new community will be made available to the public through other housing programs or public auction for residential housing development” (LOCD, 2019, 8). This was rarely, if ever, discussed publicly by state planners or policymakers and never disclosed in the state’s promotional or informational materials related to the resettlement.

State officials saw the resettlement as a way to manufacture a real estate market and establish the conditions for subsequent development of commercial real estate and businesses as part of their view of sustainability while excluding Tribal input. In an important reflective analysis, Rachel Isacoff, who worked as part of the subcontracted market analysis team, emphasizes that she never met the Tribe, never got to consider their needs and desires, but just had to run numbers on highest and best use, a concept, as applied by planners and the real estate industry, links a Lockean notion of individual property relations to economic value above all:

I was on the team that conducted a market analysis of the new resettlement site and made recommendations for housing, commercial, and retail schemes that reflected the “highest and best use” of the site. This technocratic approach to planning did not mirror the economic characteristics of the existing community and did not directly consider how well the proposed uses responded to the needs of or supported the workforce training and livelihoods of the IDJC tribe. In fact, because of the way our team (and all consultants) valued and capped time through billable hours and leaned heavily on experience from conducting past economic development analyses, no one from my firm met with the tribe during the process. (Isacoff, 2021, 198–199)

The approach to land and economic development aims were thus subsumed by state planners within what Samuel Stein refers to as the “real estate state,” decontextualized from Indigenous-led struggle to enhance or honor tribal cultural survival, land justice, livelihoods, social relations, and practical needs. According to the state’s lead resilience administrator who was leading the administration of the federal funds for the resettlement, “Like founding any new town over the course of Western history […] it's all wrapped around the idea of, how do we generate revenue? […] In Louisiana, that could mean fitness companies, pharmacies, and supermarkets chip in with funding in exchange for footholds in the new community, much like a city would on a new real estate development.” “Unlocking that financial [support] (sic) is something that will determine the success of [relocation] (sic) projects,” adds Mr. Sanders. “Ultimately we want to show that there would be the same amount of incentives the private sector has every time in any real estate development” (Gass, 2017).

Planners also decided that common areas of the new site, such as the cultural center and outdoor spaces, would serve broader publics instead of the Tribe’s distinct needs and would be maintained by Terrebonne Parish, rather than the Tribe, as was articulated in the state’s resettlement prospectus and the funded National Disaster Resilience Competition application. When Tribal leaders requested ownership of community property throughout the site to fulfill their plans for traditional herb gardens, walking paths, Tribal government offices, and several other ideas generated as part of the Tribal community-driven plans, the Office of Community Development informed them that the Tribe would have “use rights” to common areas of the resettlement but not ownership of any land. Therefore, as it currently stands at the time of this writing, the Tribe—a landowner on the Island and historical Island social institution—will have no formalized sustained collective presence at the resettlement site, and only limited individual use rights along with any other citizen or organization.

Approaching resettlement as a real estate transaction among individuals distorted the Tribe’s goals. First, it denied the Tribe itself a full set of property rights, aka the three sticks in the bundle (see Chapter 2), limiting their rights, authority, and role as the designated beneficiaries of the relocation, broadly. Second, it focused on individuals without simultaneous investment in the Tribal community as a whole as described in the state and HUD’s descriptions of beneficiaries for the grant. Third, it established a frame that prioritized the act of moving over long-term investments and ongoing Tribal consultation and resilience. Fourth, it undermined the rearticulation of Indigenous collective land tenure as a functioning land ethic and practice. Finally, framing resettlement as a real estate transaction among individuals prioritized economic development, creating new terrain for the real estate market, and enticing non-Indigenous residents. The outcome of which expropriated land and potential land rights to highest bidders instead of keeping land and land rights to support the collective well-being of the Tribe. It is difficult not to see the resemblance between these events and historical colonial land grabs and assimilation policies. The General Allotment Act of 1887, for example, enabled the President of the United States to forcibly divide land previously held in trust for Indigenous nations into parcels of property that were then allotted to individuals along with U.S. citizenship. Unallotted land was taken by the U.S. government for agriculture or sold to settlers. Allotment policy disrupted traditional forms of land tenure, place-based ecological relations, and Indigenous adaptation. The policy also came following a period of rapid U.S. imperialism westward intensified by the California Gold Rush and 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which annexed lands occupied by Mexico to the United States. Much like the reservation system and removal policies, allotment was driven by settlers’ desire for land within a cloak of paternalistic reforms aimed at assimilating Indigenous peoples. The federal government ended allotment in 1934, but by then, Indigenous lands were reduced by over 100 million acres and split up into dispersed parcels and subsumed within the colonial state’s property regime (Echo-Hawk, 2010). Option C, the public auctioning of land purchased with federal funds initially allocated for the Tribe’s community resilience mirrors the sale of “surplus” Tribal lands under allotment.

Individuation and Limitations on Receiving Community Engagement

Louisiana’s Office of Community Development emphasized residential engagement and bifurcated their approach to administering resettlement funds so that activities focused on the Island and leaving the Island were driven by a distinct set of policy objectives that differed from activities focused on redevelopment at the new site. On the Island, the primary goals articulated by the state were to move people away from coastal flood risk and to prevent those who resettle from living and rebuilding on the Island (i.e., reducing economic costs of flooded properties). It is, however, worth noting that the state’s legal inability, or unwillingness, to restrict Island redevelopment for recreational camps, created skepticism among those resettling about the state’s intentions to un-develop the Island. The state’s focus at the inland site was to nurture conditions for population and market growth as a receiving community.

The distinct modes of “community engagement” on the Island and in Schriever (the location of the inland resettlement site) reflected narrow constructions of risk and possible adaptations. State planners and contractors imposed a haphazard and individualistic outreach process on the Island that seemed aimed at decontextualizing the resettlement from existing Tribal community action for cultural survival and justice after generations of colonization, exploitation, and marginalization. As discussed further in Chapter 5, the state and contractors organized individual household interviews with some residents, and published misrepresentations and assumptions about the Island’s social organization. Practically, this de-emphasized the Tribe as a community that consisted of on/off Island Tribal relations, and instead portrayed the Island as a discrete community of individuals. While the state organized three community meetings on the Island, when these convenings became difficult for the state to manage due to ongoing debate among participants, planners and subcontractors switched to utilizing a format for meetings whereby some “stakeholders” were invited to meeting locations during a specified window of time to engage with state planners and contractors one on one. This approach enabled the agency to better control information flow and shared narratives by displacing messy group conversation and collective processing of information, and putting the responsibility of engaging on the individual, and the weighing of individual testimony, on the state agencies. The switch limited the ability to organize in larger numbers, making participation as communal action more challenging.

Meanwhile the state’s outreach to the predominantly white property owners who lived in the Schriever area adjacent to the new site was more open to the assertion of a right to act communally in so far as state planners adjusted their initial meeting format from an open house tour of plans to a group discussion where people listened to the concerns of others in a shared space face to face with state planners when the residents demanded such a conversation. The state’s administration of the resettlement funding stirred conflict within the receiving community as well. Resistance and “NIMBYism,” or “Not in My Backyard,” attitudes were expressed by the mostly white Schriever residents who lived adjacent to the inland location purchased by the state for the resettlement in ways that surprised state administrators. In addition to expressing concern about water drainage issues at the site, which continue to worry both those resettling and onlookers (Dermanksy, 2022), residents raised objections to the discrepancies between the Tribe’s initially proposed and funded plans and the state’s vision during a planning meeting hosted by the state once site designs were developed in 2019. “We were told this was going to be an Indian community,” yelled one man. “We were ok with that, but this is different. We don’t want HUD housing or Section 8. Or who moves in if these people move out?!” Fears of the resettlement site becoming “section-8” and a “normal HUD subdivision” may have been an expression of the widespread stigmatization of public housing and coded anti-black racism in the United States. It also reflects the extent to which real estate values, racial formations, and the white management of exclusion and inclusion of urban space remain mutually interdependent, including during climate resettlements.

While community outreach with individual residents is essential, research has demonstrated that the conflicts that tend to emerge in receiving areas are typically mediated by existing political economic forces and conditions. Scholars focused on environmental migration have located some sources of conflict within, for example, an existing lack of governing capacity, inadequate resource provision, and political instability in destination locations (Reuveny, 2007; Warnecke et al., 2010). Reuveny (2007) refers to these as “auxiliary influences” on resettlement outcomes. As the next section describes, such influences in the United States are shaped in large part by predation and extraction within finance, land, and real estate industries which exploit and reproduce racialized disparities in housing, wealth, and climate change-related risk, among other institutions. This means that perhaps more meaningful than funding community engagement among new neighbors, there must be more fundamental, transformative, and enduring investments into life sustaining institutions, like for example, affordable housing, in receiving areas for better resettlement processes and outcomes.

Out of the Kettle of Coastal Flooding and into the Fire of Predatory Inclusion

As the section above emphasized, while there is a lot of attention to the conflicts that can emerge throughout resettlement among resettlers and people who live in the places they are moving to, such conflicts are not typically driven by interpersonal interactions between new neighbors but rather aggravated by institutionalized inequities and power. Taking seriously the effects of auxiliary influences in producing resettlement risks in “receiving areas” requires a recognition within climate adaptation planning that the climate crisis is at once a racial capitalist crisis, an affordable housing crisis, a land crisis, a financial crisis, and a governance crisis that is produced at multiple sites and levels of government. For example, local governments determine land use and housing availability with federal funding and federal policy and rules are locally interpreted within program implementation and project development.

During the Isle de Jean Charles resettlement, Louisiana’s Office of Community Development frequently evoked legal and regulatory constraints when explaining the deviation from the Tribe’s plans and development decisions at the inland site. Among them was the Fair Housing Act—the federal policy that prevents housing discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, disability, familial status, or national origin. According to Louisiana’s Office of Community Development, “The program is open to all residents of the island, and in later phases to past residents of the island, regardless of tribal affiliation, race, color, religion, sex, national origin, familial status or disability” (LDOA, 2019). The evocation of fair housing laws while reducing possibilities for Tribal inclusion in the resettlement was striking and seemed contradictory. According to Jean Charles Choctaw Nation Chief Albert Naquin during an interview, “This doesn’t seem very fair. We know the Fair Housing was meant to prevent discrimination, but I think what they are doing is discriminating against the Tribe.”

This evocation of Fair Housing to undercut tribal planning is but one example of a long history of inconsistency in enforcing fair housing policy that goes back to the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1866, which prohibited racial discrimination in housing (Taylor, 2019; Zonta, 2019). More recently, compare HUD’s approach when the Obama Administration administered an anti-segregation rule “further affirming fair housing” by incentivizing more aggressive desegregation policies at the municipal level to the position of subsequent HUD Secretary Ben Carson’s dismissal of such efforts as “failed socialism” (Carson, 2015). Once Carson took over as HUD Secretary in 2017, HUD aggressively regulated some jurisdictions—like Los Angeles, for insufficient accessible housing availability—while turning their back on racial discrimination elsewhere and fighting to roll back the regulations against a disproportionate adverse effect on protected groups under the Fair Housing Act (Kasakove, 2019).

Two basic questions regarding the Fair Housing Act and the resettlement confounded Tribal leaders and their allies. First, why would HUD have funded something that was intended to support a Tribe’s resettlement if that was impossible under existing Fair Housing law? And second, if administering the Tribal community resettlement as was proposed and funded was illegal, then why was there not a sustained collaborative conversation and formalized agreement as to how to use discretion in order to accomplish the Tribe’s central goals of reuniting their Tribe and embracing their heritage in a way that did align with the Fair Housing Act before moving on with a more top-down planning process? According to Maldonado and Peterson (2018), one problem lies in the inability of U.S. laws to recognize communal social structures that have been prioritized in the resettlement planning. They point out that the Fair Housing Act protects the rights of individual citizens and not community rights, which are seen as essential for many “Indigenous and culturally connected communities” (ibid.). This aligns with insights of Lisa Kahaleole Hall, who has described the individualism internalized within civil rights discourse, and how this produces a tension with Indigenous nationalism:

In the United States the contemporary conception of race is firmly anchored in civil rights ideologies, the idea of equality of individuals within one nation, and does not address very different concepts of Indigenous nationhood. The logics of some forms of antiracist struggles paradoxically can undermine group identities by advocating for a form of social justice based on the equal treatment of individuals. (2008, 277)

Well-intentioned policies to protect individuals from discrimination may therefore have the unintended consequence of harming collective realities. However, there are also reasons to think that state officials may have been overstating the extent to which the Fair Housing Act was a policy barrier to using federal funds to support the Tribal community resettlement and that the matter was one of state political will and discretion.

There is also noteworthy historical precedence of exceptions to the Fair Housing Act approved by HUD when it seemed egregiously inappropriate, but these examples depended upon the exercise of bureaucratic discretion and the willingness of officials to work toward solutions. One example comes out of the fight against gentrification in San Francisco. The city wanted to use an anti-displacement “neighborhood preference” for low-income residents from certain areas in their applications to the new publicly funded Willie B. Kennedy Apartments. Essentially, the plan was to offer those who came from certain neighborhoods a priority spot in new public development “to stem the exodus of African Americans and members of other minority groups from neighborhoods that are rapidly gentrifying” (Dineen, 2016). HUD originally rejected the city’s proposed “neighborhood preference” policy because it violated the Fair Housing Act. However, after the city appealed the ruling, HUD permitted, “40 percent of the 98 units in Willie B Kennedy to be prioritized for residents who live in low-income neighborhoods undergoing displacement and experiencing advanced gentrification, as defined by a research analysis conducted by UC Berkeley” (Dineen, 2016).

Furthermore many of the legal victories that have protected at least some rights for Indigenous peoples in the United States stem from treating Tribes as political entities and not as a racial group. This has sheltered tribes from discrimination suits and from unintended consequences of the Fair Housing Act, but is a practice that is currently under attack in the Supreme Court (Nagle, 2022) and does not apply to non-federally recognized tribes. With the Indian Housing Block Grant program, HUD has also adjusted individualistic logics of the Fair Housing Act when needed. The program has waived the restrictive aspects of Fair Housing for both federally and state recognized Tribes, and if the federally funded housing is not located on land in which the Tribe has jurisdictional authority and if the federal funds are used in conjunction with other funding sources, Tribes have been able to devote housing to Tribal families. Section 201(b)(5) of Native American Housing Assistance and Self Determination Act of 1996 allows a preference for Tribal members for a subset of housing.

More generally, federal efforts to confront unfair housing, segregation, and racialized inequality have largely failed due to government accommodation of the real estate industry. In Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor describes how the end of redlining at the Federal Housing Administration and the passage of fair housing law in the late 1960s established new institutional footing for racialized structural violence, discrimination, and exploitation. Taylor tracks how programs created by the Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Act of 1968 intended to promote black homeownership, instead led to what she termed “predatory inclusion” because of the actions of appraisers and banks provided capital and new terms for the real estate industry to continue to garner profits at the expense of potential Black homeowners. The new subsidies enabled exploitation and theft at multiple levels: “Real estate agents and speculators familiar with the landscape of the Black housing market were newly partnered with appraisers, mortgage bankers, and, of course, the [Federal Housing Administration] itself, which was quite inexperienced when it came to Black buyers and the urban housing market” (2019, 147). As a congressional investigation eventually documented, speculators bought property to sell to those who would qualify for the new program and went so far as to bribe appraisers to inflate values as much as three to four times the actual worth. Many families were unable to continue paying new mortgages, resulting in HUD possessing 78,000 single-family homes from the program by 1974. Furthermore, HUD openly demonized Black families for a failure to practice responsible homeownership. Ultimately, the programs exacerbated racialized inequalities, segregation, substandard and uninhabitable housing, and ultimately stifled the ability, once again, of Black Americans to accrue wealth and benefits linked to homeownership. The failure of the program was also used by the Nixon administration as evidence that government intervention was inappropriate in housing markets and that HUD should not be housing poor and low-income families.

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor's critique of predatory inclusion extends beyond uneven enforcement of Fair Housing law to provide a detailed indictment of the extractive principles and racial structures that drive capitalism. Taylor points to layers of extraction, describing, for example, widespread exploitative practices including the use of land installment contracts, which impose higher costs on poor people and profits for those who own the mortgage as homebuyers make their payments and other rent-to-own schemes that continue in the present moment, and predatory lending, which despite the Fair Housing Act and Community Reinvestment Act continue to segregate and extract from communities of color throughout the United States (see also Bond et al., 2009; Mehkeri, 2014). Such practices have undermined wealth equality and prevented Black, Latinx, and other communities of color from wealth afforded to white families. According to Anderson (2020), the result of legal discrimination in housing through redlining accounts for a reduction of $212,000 in home equity for Black families and racialized national disparities in current homeownership, with 44% for Black families and 73.7% for white families. Additionally mortgages have become a financial asset disconnected from the land and house whose value they supposedly reflect, and investment firms and real estate giants continue to buy up property in predominantly neighborhoods inhabited by communities of color at an unprecedented rate (National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2022; Raymond et al., 2022). They acquire property cheaply perpetuating segregation and a long history of devaluing Black homes (NLIHC, 2022). Recent important scholarship on risk and uneven development reveals how interaction among real estate, insurance, visions of sustainability or resilience, and gentrification are now shaping racialized inequities in different locations across the United States (Aidoo, 2021; Checker, 2020; Keenan et al. 2018; Knuth, 2016; Taylor & Aalbers, 2022).

Resettlements are thus subsumed within wider political and economic processes—not simply the exposure to hazards and rational planning responses. Take, for example, the ways in which the resettlement funding rationale cited by the state in their application for federal funds—the deterioration of the Island Road and the unwillingness of federal agencies to enhance the road after storms—was undermined following the resettlement allocation. In 2008, the Federal Emergency Management Agency refused to fund “enhancements” to protect the two-lane, flood-prone road despite concerns from Tribal leaders. Then, the state’s resettlement funding application to HUD explicitly cited the expectation that the road will soon be impassable as a rationale for the millions in federal resettlement funding. However, since the resettlement funding allocation, multiple investments in protecting and enhancing the Road to cater to recreational fishing have materialized (Jessee, 2021). In December 2019, for example, the state provided $300,000 to the hunting and conservation non-profit Ducks Unlimited for marsh restoration south of the Road. The following year the state completed five fishing piers and small parking lots and a rock levee on Island Road using $2.4 million in BP Disaster Settlement funds. Louisiana’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries said the piers will allow “anglers” to “take advantage of the bounty in our Sportsman’s Paradise.” When these investments were initially mentioned to state planners involved in the resettlement, they were unaware of the plans and even dismissed them as rumors.

This begs the question of actual management and hubris among the planners involved who had narrow views of risk and successful adaptation shaped by status quo development and liberalism. At key points throughout the broader planning process, state officials asserted a belief that they had control of beneficial outcomes and risks when deflecting criticism. One Louisiana planner working on the resettlement shared their view that securing property ownership for individuals who move reflected the ideal of property as wealth creation. “I just think about the kind of generational wealth we are creating for Celie [an Island resident] and her family, who would probably never be able to own a home otherwise,” they reflected. “She can sell it in five years. I mean, Celie’s son will be able to go to college because of this.” This view, however, relies on multiple assumptions regarding property, value, and community not shared by Tribal leaders. First, there is the assumption that the value of the house will appreciate, and that property owners would sell or refinance, which runs counter to the notion of remaining in a new community for future generations. Second, Tribal leaders and their partners were concerned about emergent whole housing costs, like increased tax burden and utility costs, that those resettling would incur alongside new ownership of higher appraised property. Third, for at least six years following the resettlement funding, state officials maintained an all or nothing approach whereby individual property ownership came at the expense of Tribal land ownership.

Conclusion

The reality is that resettlements, and other socio-ecological adaptation strategies for that matter, do not start or end with a real estate transaction. We worry that there is not enough critical attention to the enduring structural inequities produced by the predatory practices of market actors within resettlement processes and adaptation planning more broadly. This leads to local, state, and federal accommodation of risk production, whereby institutional processes designed to reduce inequities can further entrench them. The conclusions that can be drawn about how such dynamics will shape resettlement outcomes within the Isle de Jean Charles resettlement are limited. We still do not know how development will occur at and around the new site over time, as the initial move-in of individual houses is still unfolding and disbursement of unclaimed lots and corporate development has not yet happened. We do know that the state chose an individual real estate transaction approach instead of exploring legal possibilities for nurturing collective land relations, despite the Tribal leadership’s interest in it. We also know that even the state’s vision of the resettlement was at times undermined by other agencies and private actors.

Our observations have convinced us that this is not only a matter of flawed policies at the highest level, but also that the work of defining and realizing policy and programmatic goals is never done. This points to the importance of and limits to critical exploration of legal possibilities throughout adaptation planning processes. Power influences the ways that safety and value are interpreted within policy development and, perhaps more importantly, program implementation, as well as how they change over time. More recently, safety has been aligned with value preservation as part of arguments for protection. But the ways in which public safety has been used to justify racialized violence both within the property regime and beyond (like for example to promote mass incarceration). As discussed more in the next two chapters, community structures (and communal rights) are advanced differently from individual rights as opposed to being integrated in a progressive, gradual, cautious, and prudent coordination arrangement vis a vis institutionalization of structural inequities through the markets and the state.

Existing federal policies, like Fair Housing law and the Uniform Relocation Act of 1970 (URA, 1970) discussed more in Chapter 6, as they are currently implemented, do not do enough to protect people from inequitable outcomes. In some cases, they fail to prevent the structural dynamics, racist and reactionary frames of understanding, and greed that produces inequity. For example, drawing on her work administering buyouts in New York City after Hurricane Sandy, Deborah Helaine Morris wrote, “The URA does create an assistance floor capable of providing minimum costs of a physical move from one location to another, but it does not push managed retreat programs, like mine, to imagine assistance in any other form than a remittance. Rather than address the disinvestment and exclusion that have placed certain populations in communities of risk, our program placed the burden on these vulnerable households” (Morris, 2022). Housing justice advocates and scholars have long argued for an array of approaches and more forceful regulations of the real estate industry at local, state, and federal levels, reiterating these demands in the wake of recent disasters to prevent displacement (Climate and Community Project, 2022; National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2022; Zonta, 2019).

Yet, despite the increasingly evident failures of existing policy, development, and planning norms and the seemingly novel complexities posed by the climate crisis, the fundamental challenges of risk production are not new, and perhaps neither are some of the possible solutions. Li and Spidalieri (2021) argue that receiving jurisdictions have a special role and responsibility to create more affordable housing and combat generations of racialized inequality. Carolyn Kousky, Billy Fleming, and Alan Berger’s 2021 volume, A Blueprint for Coastal Adaptation offers a multitude of existing possibilities to confront inequality and institutionalized racism within climate adaptation planning, including the expansion of public funding for affordable housing and community-driven resilient redevelopment. The NDN Collective’s 2021 Required Reading: Climate Justice, Adaptation and Investing in Indigenous Power also provides important analysis, and recommendations from their memo on “Mobilizing Climate and Environmental Justice Investments to Indigenous Frontline Communities” (NDN Collective, 2021). While the memo is focused on increasing federal investments in infrastructure like roads, utilities, and water on Indigenous territories; Native financial institutions and businesses; funding for Tribal capacity building; creating better processes for Tribes to access resilience dollars; investing in clean energy and resilience planning employment among Tribes to build and implement their adaptation plans, these goals as well as the aims of restoring Indigenous land rights and ecologies at the forefront of their landback campaign are salient to policymakers and planners at multiple levels of government and practitioners in multiple sectors. See also Climate and Community Project 2022 which warns against the influence of privatization in the midst of climate disasters and recommends investing in community planning and community institutions, public housing, local workers and unionization, decarbonization, and supporting and utilizing Traditional Ecological Knowledge. We offer additional suggestions at the end of this book, but at its core, regulating the financial extraction perpetuated by real estate markets, considering anti-displacement laws and planning constructs, and valuing communal relations in addition to property must be front and center.

References

Aidoo, F. S. (2021). Architectures of mis/managed retreat: Black land loss to green housing gains. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 11(3), 451–464.

Anguelovski, I., Connolly, J. J., Pearsall, H., Shokry, G., Checker, M., Maantay, J., Gould, K., Lewis, T., Maroko, A., & Roberts, J. T. (2019). Why green “climate gentrification” threatens poor and vulnerable populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(52), 26139–26143.

Anderson, D. (June 11, 2020). Redlining’s legacy of inequality: $212,000 less home equity, low homeownership rates for black families. Redfin News. https://www.redfin.com/news/redlining-real-estate-racial-wealth-gap/

Barra, M. P. (2021). Good sediment: Race and restoration in coastal Louisiana. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 111(1), 266–282.

Bond, P., Musto, D. K., & Yilmaz, B. (2009). Predatory mortgage lending. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(3), 412–427.

Carson, B. S. (2015, July 23). Experimenting with failed socialism again. The Washington Times. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2015/jul/23/ben-carson-obamas-housing-rules-try-to-accomplish-/

Checker, M. (2020). The sustainability myth: Environmental gentrification and the politics of justice. New York University Press.

Climate and Community Project. (2022). Toward just disaster response in the United States and US Territories. https://www.climateandcommunity.org/_files/ugd/d6378b_594920722a1b4e3393ea57629e29fbb0.pdf

Comardelle, C. (2020, October 19). Preserving our place: Isle de Jean Charles. Nonprofit Quarterly. https://nonprofitquarterly.org/preserving-our-place-isle-de-jean-charles

De Vries, D. H., & Fraser, J. C. (2012). Citizenship rights and voluntary decision making in post disaster U.S. floodplain buyout mitigation programs. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 30(1), 1–33.

Dermanksy, J. (2022, September 8). Isle de Jean Charles community members moved into the first federally funded resettlement project in Louisiana despite visible engineering issues. Desmog. https://www.desmog.com/2022/09/08/isle-de-jean-charles-relocation-new-isle-climate-change/

Dineen, J. K. (2016, August 17). Feds reject housing plan meant to help minorities stay in SF. San Francisco Chronicle.

Echo-Hawk, R. C. (2010). The magic children racial identity at the end of the age of race. Routledge.

Fleming, B., Cohen, D. A., Graetz, N., Lample, K., Lillehei, X., McDonald, K., Brave Noisecat, J., Paul, M. (2019). Public housing at risk: Adaptation through a green new deal. https://www.filesforprogress.org/memos/public_housing_at_risk.pdf

Gass, H. (2017, August 2). Tactical retreat? As seas rise, Louisiana faces hard choices. Christian Science Monitor. https://www.csmonitor.com/Environment/Inhabit/2017/0802/Tactical-retreat-As-seas-rise-Louisiana-faces-hard-choices

Hall, L. K. (2008). Strategies of erasure: US colonialism and native Hawaiian feminism. American Quarterly, 60(2), 273–280.

Isacoff, R. (2021). Identity and power: How cultural values inform decision-making in climate-based relocation. In I. J. Ajibade & A. R. Siders (Eds.), Global views on climate relocation and social justice (pp. 194–208). Routledge.

Jessee, N. (2020). Community resettlement in Louisiana: Learning from histories of horror and hope. In S. Laska (Ed.), Louisiana’s response to extreme weather—A test case for coastal resilience. Springer.

Jessee, N. (2021). Tribal leaders raise ‘serious concerns’ about plans to turn their shrinking Louisiana Island home into a ‘sportsman’s paradise’. Desmog. https://www.desmog.com/2021/07/23/isle-de-jean-charles-tribe-louisiana-sportsmans-paradise/

Jessee, N. (2022). Reshaping Louisiana’s coastal frontier: Managed retreat as colonial decontextualization. Journal of Political Ecology, 29(1). https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.2835

Kasakove, S. (2019, May 17). The tenants’ rights movement is expanding beyond big cities. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/153929/tenants-rights-movement-expanding-beyond-big-cities

Keenan, J. M., & Bradt, J. T. (2020). Underwaterwriting: From theory to empiricism in regional mortgage markets in the US. Climatic Change, 162(4), 2043–2067.

Keenan, J. M., Hill, T., & Gumber, A. (2018). Climate gentrification: From theory to empiricism in miami-dade county, florida. Environmental Research Letters, 13(5), 054001–054001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aabb32

Knuth, S. (2016). Seeing green in San Francisco: City as resource frontier. Antipode, 48(3), 626–644.

Koslov, L. (2016). The case for retreat. Public Culture, 28(2), 359–387.

Li, J., & Spidalieri, K. (2021). Home is where the safer ground is: The need to promote affordable housing laws and policies in receiving communities. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 11(4), 682–695.

Louisiana Department of Administration (LDOA). (2019). Substantial Amendment 5: Introduction of new activities and project narrative clarifications for the utilization of community development block grant funds under the National Disaster Resilience Competition (NDRC) Resettlement of Isle de Jean Charles. LDOA. https://www.doa.la.gov/media/3wwj2iyx/ndr_idjc_substantial_amendment_5-hud-approved.pdf

Maldonado, J. K., Wang, I. F. C., Eningowuk, F., Lesley, I., Lascurain, A., Lazrus, H., Naquin, C. A., Naquin, J. R., Nogueras-Vidal, K. M., Peterson, K., Rivera-Collazo, I., Souza, M. K., Stege, M., & Thomas, B. (2021). Addressing the challenges of climate-driven community-led resettlement and site expansion: Knowledge sharing, storytelling, healing, and collaborative coalition building. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 11(3), 294–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-021-00695-0

Maldonado, J. K., & Peterson, K. (2018). A community-based model for resettlement: lessons from coastal louisiana. In R. McLeman, & F. Gemenne, Routledge handbook of environmental displacement and migration (pp. 289–299). Routledge.

Mehkeri, Z. A. (2014). Predatory lending: What's race got to do with it. Public Interest Law Reporter, 20, 44.

Morris, D. H. (2021). The climate crisis is a housing crisis: Without growth we cannot retreat. In I. J. Ajibade & A. R. Siders (Eds.), Global views on climate relocation and social justice (pp. 142–151). Routledge.

Nagle, R. (November 9, 2022). The story of baby O¾ and the case that could gut native sovereignty. The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/society/icwa-supreme-court-libretti-custody-case/

National Low Income Housing Coalition. (2022). Out of reach: The high cost of housing. https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/2022_OOR.pdf

Raymond, E. L., Zha, Y., Knight-Scott, E., & Cabrera, L. (2022). Large corporate buyers of residential rental housing during the COVID-19 pandemic in three southeastern metropolitan areas. Housing Crisis Research Collaborative Research Report.

Reuveny, R. (2007). Climate change-induced migration and violent conflict. Political Geography, 26(6), 656–673.

Shi, L., & Varuzzo, A. M. (2020). Surging seas, rising fiscal stress: Exploring municipal fiscal vulnerability to climate change. Cities, 100, 102658.

Siders, A. R. (2018). Social justice implications of US managed retreat buyout programs. Climatic Change, 152(2), 239–257.

Taylor, Z. J., & Aalbers, M. B. (2022). Climate gentrification: Risk, rent, and restructuring in Greater Miami. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 112(6), 1685–1701.

Taylor, K.-Y. (2019). Race for profit: How banks and the real estate industry undermined black homeownership. UNC Press Books.

Warnecke, A., Tänzler, D., & Vollmer, R. (2010). Climate change, migration and conflict: Receiving communities under pressure? The German Marshall Fund of the United States.

Zonta, M. (2019). Racial disparities in home appreciation. Center for American Progress, 15.

Legal References

Uniform Relocation Assistance and Real Property Acquisition Policies Act, 42 U.S.C. § 4601 (1970).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jerolleman, A. et al. (2024). Market Orientation as an Environmental Hazard for Resettling Communities. In: People or Property. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36872-1_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36872-1_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-36871-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-36872-1

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)