Abstract

The article presents a bilateral update semantics for epistemic modals which captures their discourse dynamics [54] as well as their potential to give rise to fc inferences [58]. The latter are derived as neglect-zero effects as in [3]. Neglect-zero is a tendency in human cognition to disregard structures that verify sentences by virtue of an empty witness set. The upshot of modelling the neglect-zero tendency in a dynamic setting is a notion of dynamic logical consequence which makes interesting predictions concerning possible divergences between everyday and logico-mathematical reasoning.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

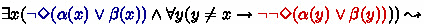

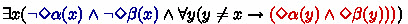

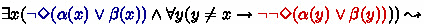

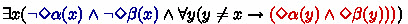

Consider approaches in the grammatical tradition. Dual Prohibition cases are not derived directly but are explained by appealing to variations of the Strongest Meaning Hypothesis [17]. To account for wide scope fc inferences, which again cannot be generated by (recursive) applications of grammatical exhaustification, different strategies must be employed (see [9, 10]). As for the case of double negation fc, as discussed in detail in [26], pages 147–149, by recursive exhaustification only we cannot capture the so-called all-others-free-choice inference displayed in (14). Inclusion-based grammatical accounts [9, 10], given some additional assumptions about alternatives, can derive the inference for ‘exactly one’ sentences but need further modifications to account for similar readings in the case of sentences using ‘exactly two’ or higher. In a logic-based account like BSML, the all-others-free-choice reading in all these variants can be captured simply by validating dual prohibition (\(\lnot \Diamond (\alpha \vee \beta ) \leadsto \lnot \Diamond \alpha \wedge \lnot \Diamond \beta \)) and double negation fc (\(\lnot \lnot \Diamond (\alpha \vee \beta ) \leadsto \Diamond \alpha \wedge \Diamond \beta \)). The former allows us to derive the blue part in the inference below and the latter the red part:

-

(i)

.

-

(i)

- 3.

For a proof-theory of BSML and related systems see [8].

- 4.

By assuming a non-indisputable accessibility relation we can also account for the lack of fc inference in the following arguably wide scope disjunction cases discussed in [41]:

-

(i)

a. It is OK for John to have ice-cream or it is OK for him to have cake.

b. It’s conceivable that she will call or it’s conceivable that she will write.

.

-

(i)

- 5.

This conjecture needs to be qualified. We do engage with zero-models in our daily life, for example when interpreting sentences with downward entailing quantifiers which can only be verified by zero-models, e.g., I have zero ideas of how to prove this or I went to the store to buy fish, but they didn’t have any, so we’ll have no fish for dinner tonight. Downward entailing quantifiers (no/zero) however are more costly to process than their upward entailing counterparts (some), a fact which can be taken to confirm the cognitive difficulty of engaging with zero-models.

- 6.

- 7.

The language of BiUS allows Boolean operations on \(\Diamond \)-formulas in contrast to Veltman’s \(L_{US}\), which precluded iteration and embedding of the \(\Diamond \)-operator. Because of this restriction, US validated idempotence (\(s[\phi ]=s[\phi ][\phi ]\)) and monotonicity (\(s\subseteq t \) implies \(s[\phi ] \subseteq t[\phi ]\)), which instead are not generally valid in BiUS. The adoption of a more liberal language is motivated by our linguistic goals. For example we want to explain wide scope free choice and the interpretation of might under negation. Some of our results however will depend on idempotence and monotonicity and, therefore, will only be valid for a fragment of the language.

- 8.

Proofs are in appendix. See also Fig. 3 for illustrations.

- 9.

Notice that Modal disjunction and Negation 1 only hold for \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \) of the restricted language \(L_{US}\). Counterexamples in the unrestricted \(L_{BiUS}\) involve formulas which violate idempotence, such as epistemic contradictions. E.g., \(|(p \wedge \Diamond \lnot p) \vee p| ^+ \not \models \Diamond (p \wedge \Diamond \lnot p) \) (counterexample to Modal Disjunction), and \(|\lnot (\lnot (p \wedge \Diamond \lnot p) \vee \lnot p)| ^+ \not \models \lnot \lnot (p \wedge \Diamond \lnot p) \) (counterexample to Negation 1).

- 10.

Proof: \(s[\lnot \lnot \phi ]= s[\lnot \phi ]^r= s[\phi ]\).

References

Aloni, M.: Conceptual covers in dynamic semantics. In: Cavedon, L., Blackburn, P., Braisby, N., Shimojima, A. (eds.) Logic, Language and Computation, vol. III. CSLI, Stanford (2000)

Aloni, M.: Free choice, modals, and imperatives. Nat. Lang. Semant. 15, 65–94 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-007-9010-2

Aloni, M.: Logic and conversation: The case of free choice. Semant. Pragmatics 15(5), 1–39 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.15.5

Aloni, M., van Ormondt, P.: Modified numerals and split disjunction: the first-order case (2021). Manuscript, ILLC, University of Amsterdam

Aloni, M., Port, A.: Epistemic indefinites crosslinguistically. In: The Proceedings of NELS 40 (2010)

Alonso-Ovalle, L.: Disjunction in alternative semantics. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst (2006)

Alonso-Ovalle, L., Menéndez-Benito, P.: Epistemic Indefinites. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2015)

Anttila, A.: The logic of free choice. Axiomatizations of state-based modal logics. Master’s thesis, ILLC, University of Amsterdam (2021)

Bar-Lev, M.E.: Free choice, homogeneity, and innocent inclusion. Ph.D. thesis, Hebrew University of Jerusalem (2018)

Bar-Lev, M.E., Fox, D.: Free choice, simplification, and innocent inclusion. Nat. Lang. Semant. 28, 175–223 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09162-y

Barker, C.: Free choice permission as resource sensitive reasoning. Semant. Pragmatics 3(10), 1–38 (2010)

Bott, O., Schlotterbeck, F., Klein, U.: Empty-set effects in quantifier interpretation. J. Semant. 36, 99–163 (2019)

Chemla, E.: Universal implicatures and free choice effects: experimental data. Semant. Pragmatics 2(2), 1–33 (2009)

Chemla, E., Bott, L.: Processing inferences at the semantics/pragmatics frontier: disjunctions and free choice. Cognition 130(3), 380–396 (2014)

Chierchia, G., Fox, D., Spector, B.: The grammatical view of scalar implicatures and the relationship between semantics and pragmatics. In: Maienborn, C., von Heusinger, K., Portner, P. (eds.) Semantics. An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning. de Gruyter (2011)

Coppock, E., Brochhagen, T.: Raising and resolving issues with scalar modifiers. Semant. Pragmatics 6(3), 1–57 (2013)

Dalrymple, M., Kanazawa, M., Kim, Y., Mchombo, S., Peters, S.: Reciprocal expressions and the concept of reciprocity. Linguist. Philos. 21(2), 159–210 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005330227480

Dayal, V.: Any as inherently modal. Linguist. Philos. 21, 433–476 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005494000753

van der Does, J., Groeneveld, W., Veltman, F.: An update on “Might". J. Log. Lang. Inf. 6, 361–380 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008219821036

Fox, D.: Free choice and the theory of scalar implicatures. In: Sauerland, U., Stateva, P. (eds.) Presupposition and Implicature in Compositional Semantics, pp. 71–120. Palgrave MacMillan, Hampshire (2007)

Franke, M.: Quantity implicatures, exhaustive interpretation, and rational conversation. Semant. Pragmatics 4(1), 1–82 (2011)

Fusco, M.: Sluicing on free choice. Semant. Pragmatics 12(20), 1–20 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.12.20

Geurts, B.: Entertaining alternatives: disjunctions as modals. Nat. Lang. Semant. 13, 383–410 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-005-2052-4

Geurts, B., Nouwen, R.: At least et al.: the semantics of scalar modifiers. Language 83(3), 533–559 (2007)

Goldstein, S.: Free choice and homogeneity. Semant. Pragmatics 12(23), 1–47 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.12.23

Gotzner, N., Romoli, J., Santorio, P.: Choice and prohibition in non-monotonic contexts. Nat. Lang. Semant. 28(2), 141–174 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-019-09160-9

Grice, H.P.: Logic and conversation. In: Cole, P., Morgan, J.L. (eds.) Syntax and Semantics, Volume 3: Speech Acts, pp. 41–58. Seminar Press, New York (1975)

Groenendijk, J., Stokhof, M.: Dynamic predicate logic. Linguist. Philos. 14(1), 39–100 (1991)

Groenendijk, J., Stokhof, M., Veltman, F.: Coreference and modality. In: The Handbook of Contemporary Semantic Theory, pp. 179–216. Blackwell (1996)

Hawke, P., Steinert-Threlkeld, S.: Informational dynamics of epistemic possibility modals. Synthese 195(10), 4309–4342 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1216-8

Incurvati, L., Schlöder, J.: Weak rejection. Australas. J. Philos. 95, 741–760 (2017)

Jayez, J., Tovena, L.: Epistemic determiners. J. Semant. 23, 217–250 (2006)

Johnson-Laird, P.N.: Mental Models. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1983)

Johnson-Laird, P., Byrne, R., Schaeken, W.: Propositional reasoning by model. Psychol. Rev. 99, 418–439 (1992)

Kamp, H.: Free choice permission. Proc. Aristot. Soc. 74, 57–74 (1973)

Kaufmann, M.: Free choice is a form of dependence. Nat. Lang. Semant. 24(3), 247–290 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-016-9125-4

Krahmer, E., Muskens, R.: Negation and disjunction in discourse representation theory. J. Semant. 12(4), 357–376 (1995)

Kratzer, A., Shimoyama, J.: Indeterminate pronouns: the view from Japanese. In: Lee, C., Kiefer, F., Krifka, M. (eds.) Contrastiveness in Information Structure, Alternatives and Scalar Implicatures. SNLLT, vol. 91, pp. 123–143. Springer, Cham (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10106-4_7

Lück, M.: Team logic: axioms, expressiveness, complexity. Ph.D. thesis, University of Hannover (2020)

Mandelkern, M.: Coordination in conversation. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2017)

Meyer, M.C.: Free choice items disjunction – “an apple or a pear”. In: The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Semantics. Wiley Blackwell (2020)

Nieder, A.: Representing something out of nothing: the dawning of zero. Trends Cogn. Sci. 20, 830–842 (2016)

Quelhas, A., Rasga, C., Johnson-Laird, P.: The analytic truth and falsity of disjunctions. Cogn. Sci. 43, e12739 (2019)

Ross, A.: Imperatives and logic. Theoria 7, 53–71 (1941)

Rumfitt, I.: ‘Yes and No’. Mind 109, 781–823 (2000)

Schulz, K.: A pragmatic solution for the paradox of free choice permission. Synthese 142, 343–377 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-005-1353-y

Schwarz, B.: Consistency preservation in quantity implicature: the case of at least. Semant. Pragmatics 9(1), 1–47 (2016)

Simons, M.: Dividing things up: the semantics of or and the modal/or interaction. Nat. Lang. Semant. 13(3), 271–316 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-004-2900-7

Smiley, T.: Rejection. Analysis 56(1), 1–9 (1996)

Tieu, L., Romoli, J., Zhou, P., Crain, S.: Children’s knowledge of free choice inferences and scalar implicatures. J. Semant. 33(2), 269–298 (2016). https://academic.oup.com/jos/article-abstract/33/2/269/2413864?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Väänänen, J.: Dependence Logic. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2007)

Väänänen, J.: Modal dependence logic. In: Apt, K.R., van Rooij, R. (eds.) New Perspectives on Games and Interaction, pp. 237–254. Amsterdam University Press (2008)

Van Tiel, B., Schaeken, W.: Processing conversational implicatures: alternatives and counterfactual reasoning. Cogn. Sci. 105, 93–107 (2017)

Veltman, F.: Defaults in update semantics. J. Philos. Log. 25, 221–261 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00248150

von Wright, G.: An Essay on Deontic Logic and the Theory of Action. North Holland (1968)

Yalcin, S.: Epistemic modals. Mind 116(464), 983–1026 (2007)

Yang, F., Väänänen, J.: Propositional team logics. Ann. Pure Appl. Logic 168, 1406–1441 (2017)

Zimmermann, E.: Free choice disjunction and epistemic possibility. Nat. Lang. Semant. 8, 255–290 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011255819284

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments which led to substantial improvements. I am also grateful to Marco Degano for discussion and to Bo Flachs for his help with some of the proofs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 BiUS, US and PL

Theorem 1

\(\alpha _1, \dots , \alpha _n \models _{BiUS} \beta \text { iff } \alpha _1, \dots , \alpha _n \models _{US} \beta \ [\text {if } \alpha _1,... , \alpha _n, \beta \in L_{US}]\)

Proof

We only need to check the case of negation, i.e. show that \(s[\gamma ]^r=s - s[\gamma ] \) for all s and \(\gamma \in L_{PL}\) (recall that \(\Diamond \) cannot appear in the scope of negation in \(L_{US}\)). We prove this by induction on the complexity of \(\gamma \).

-

(i)

\(s[p]^r = s \cap \{w \in W \mid V(p,w)=0\} =s - \{w \in W \mid V(p,w)=1\} = s - W[p]=s- s[p]\)

-

(ii)

\(s[\alpha \wedge \beta ]^r= s[\alpha ]^r \cup s[\beta ]^r =_{IH} (s - s[\alpha ) \cup (s - s[\beta ])= s -(s[\alpha ] \cap s[\beta ]) = s - s[\alpha \wedge \beta ]\)

-

(iii)

\(s[\alpha \vee \beta ]^r= s[\alpha ]^r \cap s[\beta ]^r =_{IH} (s - s[\alpha ]) \cap (s - s[\beta ])= s -(s[\alpha \cup s[\beta ) = s - s[\alpha \vee \beta ]\)

-

(iv)

\(s[\lnot \alpha ]^r= s[\alpha ]\). Since \({s[\alpha ]\subseteq s}\) by eliminativity, \( s[\alpha ]=s -(s - s[\alpha ]) =_{IH} s - s[\alpha ]^r = s - s[\lnot \alpha ]\).

Theorem 2

\(\alpha _1, \dots , \alpha _n \models _{BiUS} \beta \text { iff } \alpha _1, \dots , \alpha _n \models _{PL} \beta \ [\text {if } \alpha _1,\dots , \alpha _n, \beta \in L_{PL}]\)

Proof

This follows from the fact that in BiUS (just like in US, see [54], page 231), all \(\alpha \in L_{PL}\) are such that for any s, \(s[\alpha ]= s \cap W[\alpha ]\).

1.2 Ignorance and Free Choice

The proofs of the facts below use the following lemmas.

Lemma 1

For \(\alpha \in L_{BiUS}\) and ne-free, and any state s.

-

(i)

If \(s[|\alpha |^+] \) is defined, then \(s[|\alpha |^+] = s[\alpha ]\)

-

(ii)

If \(s[|\alpha |^+]^r\) is defined, then \(s[|\alpha |^+]^r = s[\alpha ]^r\)

Proof

By an easy double induction on the complexity of \(\alpha \).

Lemma 2

For \(\alpha \in L_{US}\) and any state s.

-

(i)

Idempotence: \(s[\alpha ]=s[\alpha ][\alpha ]\) and \(s[\lnot \alpha ]=s[\lnot \alpha ][\lnot \alpha ]\)

-

(ii)

Monotonicity: \(s\subseteq t \) implies \(s[\alpha ] \subseteq t[\alpha ]\)

-

(iii)

Downward closure of \(\lnot \alpha \): \(s\subseteq t \) implies \(t[\lnot \alpha ]=t\) \(\Rightarrow \) \(s[\lnot \alpha ]=s\).

Proof

These properties are consequences of the following two facts: (a) in \(L_{US}\) all might-formulas have the form \(\Diamond \alpha \), where \(\alpha \) is \(\Diamond \)-free; (b) all \(\Diamond \)-free \(\alpha \) (i.e., \(\alpha \in L_{PL}\)) are such that for all s, \(s[\alpha ]= s \cap W[\alpha ]\).

Lemma 3

(Eliminativity). For \(\phi \in L_{BiUS}\) and any state s.

-

If \(s[\phi ]^{(r)}\) is defined, then \(s[\phi ]^{(r)}\subseteq s\)

Fact 1

(Modal Disjunction). \(|\alpha \vee \beta |^{+} \models \Diamond \alpha \wedge \Diamond \beta \) (if \(\alpha ,\beta \in L_{US}\))

Proof

Suppose \(s[ |\alpha \vee \beta |^{+}]\) is defined. Then \(s[ |\alpha \vee \beta |^{+}]\) = \(s[|\alpha |^+] \cup s [|\beta |^{+}]\) with both \(s[|\alpha |^+]\) and \( s[|\beta |^+]\) defined and \(\ne \emptyset \). By Lemma 1 we have \(s[|\alpha |^+]=s[\alpha ]\ne \emptyset \). From \(s[|\alpha |^{+}] \subseteq s[|\alpha \vee \beta |^{+}]\) it follows \(s[\alpha ] \subseteq s[|\alpha \vee \beta |^{+}]\). By monotonicity of \(\alpha \) (Lemma 2) we conclude \(s[\alpha ] [\alpha ]\subseteq s[|\alpha \vee \beta |^{+}][\alpha ]\). Since \( s[\alpha ][\alpha ]=s[\alpha ] \ne \emptyset \) (by idempotence of \(\alpha \)), we conclude \(s[ |\alpha \vee \beta |^{+}] [\alpha ] \ne \emptyset \). But then \(s[|\alpha \vee \beta |^{+}] \models \Diamond \alpha \). Similarly for \(\Diamond \beta \).

For a counterexample to Modal Disjunction with \(\alpha \not \in L_{US}\), let \(\alpha \) be \( (p \wedge \Diamond \lnot p) \). Then \(\{w_p, w_{\emptyset }\} [|(p \wedge \Diamond \lnot p) \vee p| ^+] =\{w_p\}\) is defined but does not support \(\Diamond (p \wedge \Diamond \lnot p)\). Thus \(|(p \wedge \Diamond \lnot p) \vee p| ^+ \not \models \Diamond (p \wedge \Diamond \lnot p)\).

Fact 2

(Narrow Scope fc ). \(|\Diamond (\alpha \vee \beta )|^+ \models \Diamond \alpha \wedge \Diamond \beta \)

Proof

Suppose \(s [|\Diamond (\alpha \vee \beta )|^+ ] \) is defined. Then \(s [|\Diamond (\alpha \vee \beta )|^+ ]= s [\Diamond |(\alpha \vee \beta )|^+]= s\ne \emptyset \) and \(s [| \alpha \vee \beta |^+] = s[| \alpha |^+] \cup s[|\beta |^+] \ne \emptyset \). It follows that \(s[|\alpha |^+] \ne \emptyset \ne s[|\beta |^+]\). By Lemma 1 we conclude \(s[\alpha ] \ne \emptyset \). Hence \(s[|\Diamond (\alpha \vee \beta )|^+][\Diamond \alpha ]=s \) and thus \(s[|\Diamond (\alpha \vee \beta )|^+] \models \Diamond \alpha \). Similarly for \(\Diamond \beta \).

Fact 3

(Wide Scope fc ). \(|\Diamond \alpha \vee \Diamond \beta |^+ \models \Diamond \alpha \wedge \Diamond \beta \)

Proof

Suppose \(s [|\Diamond \alpha \vee \Diamond \beta |^+ ]\) is defined. Then \(s [|\Diamond \alpha \vee \Diamond \beta |^+]=s[|\Diamond \alpha |^+ \vee |\Diamond \beta |^+] = s[|\Diamond \alpha |^+] \cup s[|\Diamond \beta |^+]=s\ne \emptyset \). Hence both \(s[|\Diamond \alpha |^+]\) and \(s[|\Diamond \beta |^+]\) are defined which means \( s[\Diamond |\alpha |^+]= s[\Diamond |\beta |^+] =s \ne \emptyset \). It follows that \(s[|\alpha |^+] \ne \emptyset \ne s[|\beta |^+]\). By Lemma 1 we conclude \(s[\alpha ] \ne \emptyset \). Hence \(s[|\Diamond \alpha \vee \Diamond \beta |^+ ][\Diamond \alpha ]=s \) and thus \(s[|\Diamond \alpha \vee \Diamond \beta |^+ ] \models \Diamond \alpha \). Similarly for \(\Diamond \beta \).

Fact 4

(Negation 1). \(|\lnot (\alpha \vee \beta )|^+ \models \lnot \alpha \wedge \lnot \beta \) (if \(\alpha ,\beta \in L_{US}\))

Proof

Suppose \(s[ |\lnot (\alpha \vee \beta )|^{+}]\) is defined. Then \(s[| \lnot (\alpha \vee \beta )|^{+}]\) = \(s[|\alpha |^+ \vee |\beta |^+]^r =\) \( s[|\alpha |^+]^r \cap s[|\beta |^+]^r \). By Lemma 1 we have \(s[|\alpha |^+]^r=s[\alpha ]^r =s[\lnot \alpha ]\ne \emptyset \). From \( s[|\lnot (\alpha \vee \beta )|^{+}] \subseteq s[|\alpha |^+]^r\) we have then \( s[|\lnot (\alpha \vee \beta )|^{+}] \subseteq s[\lnot \alpha ]\). By idempotence, \(s[\lnot \alpha ] =s[\lnot \alpha ] [\lnot \alpha ]\), and by downword closure, \( s[|\lnot (\alpha \vee \beta )|^{+}] = s[|\lnot (\alpha \vee \beta )|^{+}] [\lnot \alpha ]\). Hence \(s[|\lnot (\alpha \vee \beta )|^{+}] \models \lnot \alpha \). Similarly for \(\lnot \beta \).

Fact 5

(Negation 2 ). \(|\lnot \Diamond (\alpha \vee \beta )|^+ \models \lnot \Diamond \alpha \wedge \lnot \Diamond \beta \)

Proof

Suppose \(s[ |\lnot \Diamond (\alpha \vee \beta )|^{+}]\) is defined. Then \(s[| \lnot \Diamond (\alpha \vee \beta )|^{+}] = s[\Diamond |(\alpha \vee \beta )|^{+}]^r \ne \emptyset \). This means that \(s[\Diamond |(\alpha \vee \beta )|^{+}]^r =s\) and so also \(s[|(\alpha \vee \beta )|^{+}]^r = s[|\alpha |^+ \vee |\beta |^+]^r = s[|\alpha |^+]^r \cap s[|\beta |^+]^r =s\). By Lemma 1, \(s[|\alpha |^+]^r = s[\alpha ]^r\) and so \(s\subseteq s[\alpha ]^r\). By eliminativity, \(s[\alpha ]^r=s\) and so \(s[\Diamond \alpha ]^r=s\) and \(s[\lnot \Diamond \alpha ] =s\). Hence \(s[|\lnot \Diamond (\alpha \vee \beta )|^{+}] \models \lnot \Diamond \alpha \). Similarly for \(\lnot \Diamond \beta \).

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Aloni, M. (2023). Neglect-Zero Effects in Dynamic Semantics. In: Deng, D., Liu, M., Westerståhl, D., Xie, K. (eds) Dynamics in Logic and Language. TLLM 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13524. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25894-7_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25894-7_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-25893-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-25894-7

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)