Abstract

From the philosophical perspective presented in the first part of this book, together with the clinical application of this framework in the second part, it follows that we must change the way we approach causal evidence of health and illness conceptually, methodologically and practically. This has some practical consequences for the clinical encounter, as discussed throughout the book. We here offer some specific CauseHealth recommendations for making causal evidence more clinically relevant and better informed by the clinical encounter. The recommendations follow from an overall consideration of the previous chapters, both the philosophical framework and its clinical implications.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

We have presented an overview of the philosophical framework of CauseHealth and shown how it relates to the clinical encounter. By giving some examples of how the abstract philosophical ideas (Part I) can be implemented into clinical practice (Part II), we hope to have shown how ontological and other foundational considerations are relevant for healthcare professionals. We also hope to have demonstrated that a change toward a genuinely person centred practice cannot happen without a corresponding change in the ontology, norms and methods underlying that practice. Finally, we hope to have empowered and inspired healthcare practitioners to get involved in debates about the foundation of medicine and healthcare and how implicit philosophical assumptions shape and define their profession.

1 Practical Recommendations for Change

From the philosophical perspective presented in the first part of this book, taken together with the clinical application of this in the second part, it should now be clear that we must change the way we approach causal evidence of health and illness conceptually, methodologically and practically. This has some practical consequences for the clinical encounter, as discussed throughout the book. We now offer some specific CauseHealth recommendations for making causal evidence more clinically relevant and better informed by the clinical encounter. The recommendations follow from an overall consideration of the previous chapters, both the philosophical framework and its clinical implications.

-

Assume medical uniqueness, because there is no normal, standard or statistically average patient.

Individual dispositions and propensities are given by intrinsic properties and their interactions within a unique context. What will happen in such a unique context with a unique set of dispositions can therefore not be derived directly from what happens in similar contexts, for instance in a population of similar individuals. Assuming causal complexity, context-sensitivity and causal singularism, each causal process will be unique, including a unique combination of dispositions. This unique combination of dispositions come from the patient and their total situation. The idea of an average patient is therefore a statistical artefact: in the clinical reality, the standard or average patient does not exist.

-

Treatment should be adapted rather than standardised, because no two patients are causally equal.

Since causality is intrinsic and unique to a specific context, it follows that an equivalent intervention in two different patients might amount to different medical treatments. Decisions on treatment ought therefore to be tailored to the individual rather than derived from statistical evidence alone. The default expectation is that treatment cannot be standardised, but must instead be adapted to the patient in their specific context, with their unique set of dispositions, aims and preferences at that particular stage of their illness or recovery process. This also means that clinical knowledge and judgement is vital for making decisions about how to proceed with the individual seeking care.

-

Value qualitative approaches, because causal evidence is much more than evidence from RCTs.

There is no perfect method for establishing causality in the dispositionalist sense; i.e., that the effect was a result of intrinsic dispositions interacting. Instead, we need a plurality of methods and multiple types of evidence. This means that the meaning of ‘evidence’ needs to be expanded, and not be restricted to evidence from experiments and controlled setups. Qualitative approaches based on clinical dialogue and observation have a huge potential for understanding which causal elements and mechanisms are in place in the individual case. Indeed, qualitative approaches can contribute to study complex causal interactions between multiple factors from biology, social context, medical history, genetics and lifestyle. Causal evidence must also include evidence from the specific patient who is supposed to benefit from the intervention.

-

Consider mechanistic and theoretical knowledge, because we need to understand hows and whys.

If the healthcare practitioner is to make rational clinical choices for their patients, it is important to consider the plausible causal mechanisms underlying statistical evidence. This means that, for the purpose of the single case, theoretical knowledge about how and why different causes interact to produce the effect must be given epistemic priority over how often an intervention is followed by the effect in a studied population. We must seek to understand causal mechanisms and not be satisfied with evidence from correlation data and comparisons of these. Indeed, knowing what happens to other patients is most useful for clinical decisions for the single patient when we also know why it happened and which dispositional properties were causally relevant for the outcome.

-

Accept clinical uncertainty, because precise quantitative estimates do not reflect reality.

Causal knowledge and evidence will never be complete, so clinical uncertainty is ineliminable. Any causal process can be interfered with by introducing additional dispositions, and all real-life situations are open systems with an unlimited number of causally relevant factors or dispositions. The lack of certain predictions thus reflects the reality of the clinic. Any prediction made with precise numeric estimates can only come from assuming an idealised model in a deterministic and closed system, using an algorithm to calculate the probability of an outcome. Such predictions might seem certain, but no such certainty can be transferred to practice. Dispositions and propensities do not generate clearly quantifiable predictions, but rather point to qualitative and contextual considerations.

-

Consider individual propensities, because they affect the risk and safety of treatment.

To understand how an intervention works and which contextual factors might influence the outcome is crucial for assessing potential benefits and harms that the intervention might have for different individuals. This must also include a consideration of long-term effects. For this, we need to consider not only the dispositions of the intervention, but also the unique, individual propensities of the person receiving care and the causally relevant dispositions represented by their life situation. Risk and safety must be considered on the individual level instead of something that can be directly derived from frequencies in populations. Specific care must be taken to pick up on the patient’s vulnerability to the intervention.

-

Know your patient, because most of the causally relevant evidence will come from there.

Causal evidence comes not only from clinical studies and medical research, but also from the patient context. Their biography, genetics, medical history, lifestyle, diet and life situation will represent most of the causally relevant information needed to understand and make predictions in this case. The more we know about the patient, the better we understand their condition and the more causal evidence we have for making good and safe clinical decisions.

-

Study unexpected outcomes, because there is much to be learned from outliers and marginal cases.

Theoretical knowledge of complex causal interactions cannot easily be gained from controlled experiments alone, where single factors are studied in isolation from background conditions. Only in the single patient will this causal complexity be observed. In marginal and outlier cases, where unexpected or rare outcomes occur, we might be able to observe hitherto unknown causal interactions in a unique combination. Such outlier cases should be studied in detail, since they are an opportunity to learn more about causal mechanisms from rare interactions and contextual interferers.

-

Clinical evidence should inform research, because that is where causal complexity is observed.

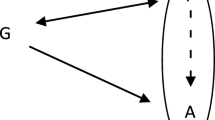

Since the clinical encounter offers us a chance to investigate causal mechanisms in their full real-life complexity, the medical community should make the most out of this opportunity. For instance, when the clinical inquiry is done in a whole person centred way, those results can feed back to basic and clinical research with new causal hypotheses. Information will thus flow from the clinic to research and not only from research to the clinic.

-

Listen to the story, because ‘medically unexplained’ does not equal ‘no causal explanation’.

That a condition is medically unexplained does not necessarily mean that no causal explanation for the symptoms can be given in the individual case. Sometimes, ‘medically unexplained’ means simply that none of the causes suspected by the patient or clinician can be backed up by statistical evidence. Although observed repetition would have been a good reason to accept it as a medical cause, causal singularism suggests that no such repetition is required for it to count as a cause, ontologically speaking. The patient’s story is a vital source of causal insight into the unique complexity of their condition.

-

Rebel, because medicine and healthcare must move beyond positivist scientific ideals.

What counts as ‘scientific’ is too narrowly defined within the current medical paradigm, with emphasis on quantitative data and comparisons of these. Alternatives to these positivist ideals should be welcomed. For instance, clinical reasoning should take into account patient narratives and embodied lived experiences as key sources for investigating causes and effects in the single case. Dispositionalism calls for a radical change in medicine and healthcare, away from reductionism, standardisation, fragmentation and medicalisation, and toward an ecological, phenomenological, whole-ist and genuinely person centred approach.

2 Toward a New Paradigm

We are not questioning the idea that medicine and healthcare should be evidence based. On the contrary, we want to challenge the definition of ‘evidence’, and specifically of ‘causal evidence’. From a dispositionalist perspective, what counts as causal evidence is much broader than what is suggested by the current framework. We wish therefore to see the rise of a new paradigm, in which healthcare decisions are not seen as ‘evidence based’ until they include all the causally relevant evidence. This means that we need to consider, not only evidence from general knowledge and research on populations, but crucially also qualitative and phenomenological evidence from the particular encounter with the patient. Downgrading the latter as ‘less scientific’, ‘less reliable’, ‘anecdotal’ or ‘secondary’, implies an unspoken commitment to a very specific philosophical bias about causation, as we have seen. When translated into clinical practice, those philosophical biases carry an inherent risk of delivering a poorer, de-humanised, fragmented and at times counter-productive healthcare, as the testimonies in this book so powerfully warn.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Anjum, R.L., Copeland, S., Rocca, E. (2020). Conclusion: CauseHealth Recommendations for Making Causal Evidence Clinically Relevant and Informed. In: Anjum, R.L., Copeland, S., Rocca, E. (eds) Rethinking Causality, Complexity and Evidence for the Unique Patient. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41239-5_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41239-5_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-41238-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-41239-5

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)