Abstract

This introductory chapter will blend both legal and technical aspects of microgeneration systems in order to acquaint the readers with the concept and roles of microgeneration systems, the perception of the European Union and the ways of promotion and development through policies and legal instruments. These notions are fundamental for readers and practitioners in the field of microgeneration systems since a variety of factors work in close connection and have a profound influence on the development of microgeneration systems. This chapter will make short explanatory remarks about the evolution (1) of the European Union and the energy sector in Europe in the transition to decentralised energy production and extensive use of microgeneration systems. Afterwards, the challenges (2) confronting the European energy sector are presented in order to understand the way problems are tackled by the European Union through policies (3) and legal instruments (4) to comprehend the use, promotion and trend for development of microgeneration systems (5).

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Article 2, Para’s 1 and 2 of TFEU

“1. When the Treaties confer on the Union exclusive competence in a specific area, only the Union may legislate and adopt legally binding acts, the MS being able to do so themselves only if so empowered by the Union or for the implementation of Union acts.

2. When the Treaties confer on the Union a competence shared with the MS in a specific area, the Union and the MS may legislate and adopt legally binding acts in that area. The MS shall exercise their competence to the extent that the Union has not exercised its competence. The MS shall again exercise their competence to the extent that the Union has decided to cease exercising its competence”.

- 2.

Article 4, Para. 2 of TFEU

“1. Shared competence between the Union and the MS applies in the following principal areas:

(i) energy.

- 3.

Article 194, Para. 1 of TFEU

“1. In the context of the establishment and functioning of the internal market and with regard for the need to preserve and improve the environment, Union policy on energy shall aim, in a spirit of solidarity between MS, to:

(a) ensure the functioning of the energy market;

(b) ensure security of energy supply in the Union;

(c) promote energy efficiency and energy saving and the development of new and renewable forms of energy; and

(d) promote the interconnection of energy networks”.

- 4.

The increase in environmental movements in the 1950s brought the concern for “sustainable development”. However, it was not until 1987, when the United Nations released the Brundtland Report (Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future) that the notion of “sustainable development” was firstly framed (“development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”).

- 5.

Since 1985, the ECJ sought the importance of environmental protection in Procureur de la République v. Association de Défense des Bruleurs d'Huiles Usagées (See ECJ Case C-240/83). Sustainable developments was first enshrined in the Maastricht Treaty (1992) and reinforced in the Amsterdam Treaty (1997).

- 6.

Conerstones: 1990s, 2003, 2006, 2009 and lastly 2012.

- 7.

The energy markets were dominated by national monopolies that wanted to preserve their status quo. See also Sect. 2.

- 8.

For instance in France, where the markets were dominated by giants such as EDF and GDF.

- 9.

The unbundling process started from unbundling Transmission System Operators (TSOs), Distribution System Operators (DSOs) to nowadays unbundling consumers, the last link in the energy chain and engaging them in the internal energy market. This is also the reason for previously starting directly from the downstream market of microgeneration systems.

- 10.

- 11.

The climate and energy package: EU Emissions Trading Directive (EU ETS 2009/29/EC), Effort Sharing Decision (non-ETS 406/2009/EC), Carbon capture and geological storage (CCS 2009/31/EC) and Renewable Energy Sources Directive (RES 2009/28/EC).

- 12.

- 13.

- 14.

Article 1.

- 15.

Article 1.

- 16.

Preamble 1.

- 17.

Preamble 51.

- 18.

Article 37, (1), (j).

- 19.

Article 37, (1), (p).

- 20.

Annex I.

- 21.

Article 36, (d).

- 22.

Article 1 (Subject matter and scope).

- 23.

Preamble, Point (1): “Reduce greenhouse gas emissions”, “promoting security of supply” and “promoting technological developments and innovation”.

- 24.

Preamble, Point (4): “regional and local development, export prospects ” and Preamble, Point (6): “utilisation of local energy sources, increased local security of supply, shorter transport distances and reduced energy transmission losses”.

- 25.

Preamble, Point (4): “social cohesion and employment opportunities” and Preamble, Point (6): “income sources and creating jobs locally”.

- 26.

Preamble, Point (43).

- 27.

Article 13 (Administrative procedures, regulations and codes), (f): “simplified and less burdensome authorisation Procedures, including through simple notification if allowed by the applicable regulatory framework, are established for smaller projects and for decentralised devices for producing energy from renewable sources, where appropriate”.

- 28.

Defined by Article 2, (k) as “any instrument, scheme or mechanism applied by a Member State or a group of MS, that promotes the use of energy from renewable sources by reducing the cost of that energy, increasing the price at which it can be sold, or increasing, by means of a renewable energy obligation or otherwise, the volume of such energy purchased”.

- 29.

Article 13, (e): “administrative charges paid by consumers … are transparent and cost related”.

- 30.

Article 14, (1): “MS shall ensure that information on support measures is made available to all relevant actors, such as consumers…”.

- 31.

Article 14, (6): “MS … shall develop suitable information, awareness raising, guidance or training programmes in order to inform citizens of the benefits and practicalities of developing and using energy from renewable sources”.

- 32.

Article 15, (1): “For the purposes of proving to final customers the share or quantity of energy from renewable sources … MS shall ensure that the origin of electricity produced from renewable energy sources can be guaranteed as … in accordance with objective, transparent and non-discriminatory criteria”.

- 33.

Preamble, Point (3).

- 34.

Preamble, Point (7).

- 35.

Article 2, (4) as “the calculated or measured amount of energy needed to meet the energy demand associated with a typical use of the building, which includes, inter alia, energy used for heating, cooling, ventilation, hot water and lighting”.

- 36.

Article 1, (1).

- 37.

Article 2, (12): ‘energy performance certificate’ means a certificate recognised by a Member State or by a legal person designated by it, which indicates the energy performance of a building or building unit, calculated according to a methodology adopted in accordance with Article 3.

- 38.

Article 11, (1).

- 39.

Article 12, (4).

- 40.

However, for single building units rented out, MS can defer the application until 31 December 2015 as stated by Article 28, Para. 4.

- 41.

Article 12, (1), (a).

- 42.

Article 14, (1).

- 43.

Article 15, (1).

- 44.

Article 4, Para. 2: “ MS may decide not to set or apply the requirements referred to in paragraph 1 to the following categories of buildings: (a) buildings officially protected as part of a designated environment or because of their special architectural or historical merit, in so far as compliance with certain minimum energy performance requirements would unacceptably alter their character or appearance; (d) residential buildings which are used or intended to be used for either less than 4 months of the year or, alternatively, for a limited annual time of use and with an expected energy consumption of less than 25 % of what would be the result of all-year use; (e) stand-alone buildings with a total useful floor area of less than 50 m2”.

- 45.

Article 6, (1).

- 46.

Article 9, (1).

- 47.

Article 7, (1).

- 48.

Article 8, (2).

- 49.

Article 10, (6) and (7).

- 50.

Article 11, (4).

- 51.

Preamble 10.

- 52.

Article 1, (1).

- 53.

Article 1, (1).

- 54.

Preamble 8.

- 55.

Annex I Part II.

- 56.

Art 2, Points (38), (39).

- 57.

Preamble 38.

- 58.

Article 3.

- 59.

Article 4.

- 60.

Article 5.

- 61.

Article 6—“purchase only products, services and buildings with high energy-efficiency performance”.

- 62.

Annex XI, (2), (d).

- 63.

Article 9, Para. 2 (c).

- 64.

Article 12, Para. 1.

- 65.

Article 19.

- 66.

Article 15, Para. 5.

- 67.

Article 15, Para. 7.

- 68.

Article 15, Para. 1.

- 69.

Article 15, Para. 4.

- 70.

Article 12, Para. 2.

- 71.

Preamble 49.

- 72.

Article 20, Para. 4.

- 73.

Preamble 53.

- 74.

Article 1.

- 75.

Preamble 45.

- 76.

Preamble 1.

- 77.

Preamble 19.

- 78.

Preamble 33.

- 79.

See the incentives promoted by the Energy Efficiency Directive.

- 80.

“Efficiency is doing the things right; effectiveness is doing the right things”.

References

European Commission (2012) Making the internal energy market work. COM 663 final, Brussels, p 2

Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 on energy efficiency, amending Directives 2009/125/EC and 2010/30/EU and repealing Directives 2004/8/EC and 2006/32/EC (2012) OJ L315, pp. 1–56, Preamble 1

Pinder J (1998) The building of the European Union, 3rd edn. OUP, Oxford, p 3

Europea Union (2014), The history of the European Union, http://europa.eu/about-eu/euhistory/index_en.htm

Potocnik J (2006) European smart grids technology platform—vision and strategy for Europe’s electricity networks of the future. European Commission, Brussels, foreword

European parliament (2010) Directorate general for internal policies, policy department a: economic and scientific policy—industry, research and energy. Decentralized Energy Systems, Brussels

DKE German Commission for Electrical, Electronic and Information Technologies (2010) The German national smart grid standardization strategy. CIM User Group, Milan, p 4

Potocnik J (2006) European Smart Grids Technology Platform—Vision and strategy for Europe’s electricity networks of the future. European Commission, Brussels, p 6

Potocnik J (2006) European SmartGrids Technology Platform—Vision and strategy for Europe’s electricity networks of the future. European Commission, Brussels, foreword, p 6

International Energy Agency (2011) Technology roadmap—smart grids. © OECD/IEA, Paris, p 6. (www.iea.org)

Badea GV et al (2013) The legal framework for microgeneration systems in the deployment of Smart Grids, MicrogenIII. In: Proceedings of the 3rd edn. of the international conference on microgeneration and related technologies, Naples, 15–17 April 2013, pp 834–841

Micropower Europe (2010) Mass market microgeneration in the European union—from vision to reality. Brussels, p 3

Wikipedia (2013) Microgeneration. Web. (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microgeneration)

European Commission (2007) An energy policy for Europe. COM 1 final, Brussels, p 3

University of Leipzig (2014) Energy fundamentals. Web (uni-leipzig.de/~energy/ef/01.htm)

Carr T (1974) Testimony to U.S. Senate Commerce Committee

European Commission (2013) Energy challenges and policy. Brussels, p 2

European Commission (2013) Energy challenges and policy. Brussels, pp 3–6

European Parliament, Directorate General for Internal Policies, Policy Department A: Economic And Scientific Policy—Industry, Research and Energy (2010) Decentralized energy systems. Brussels, pp 64–71

European Commission (2013) Energy challenges and policy. Brussels, pp 4–7

European Parliament, Directorate General for Internal Policies, Policy Department A: Economic And Scientific Policy—Industry, Research and Energy (2010) Decentralized energy systems. Brussels, pp 73–76

European Commission, European Smart Grids Technology Platform (2006) Vision and strategy for Europe’s electricity networks of the future. Brussels, p 12

European Commission (2013) Energy challenges and policy. Brussels, p 1

Eszter T (2006) Different approached of sustainable development—the global level, the EU guideline and the success of local implementation. Budapesti Gazdasági Főiskola, pp 17–22

Taoiseach EK et al (2012) Our sustainable future—a framework for sustainable development for Ireland. p 10

European Commission (2013) Energy challenges and policy. Brussels, p 3

Map. Available at: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/environment/air_greenhouse_emissions.htm

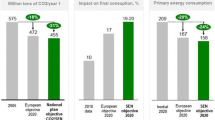

European Commission. EU greenhouse gas emissions and targets. Available at: ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/g-gas/

European Environment Agency (2013) Trends and projections in Europe 2013—tracking progress towards Europe’s climate and energy targets until 2020. Report No 10/2013. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. See also EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) data viewer, European Environment Agency. www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/data-viewers/emissions-trading-viewer. Accessed 24 Sept 2013. And European Union Transaction Log (EUTL) (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/ets)

Available at: http://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/absolute-change-of-ghg-emissions-2

Eurostat—EU 27 (2010) Production of primary energy. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Energy_production_and_imports

European Commission (2013) Energy challenges and policy. Brussels, p 16

European Commission (2013) Energy challenges and policy. Brussels, p 17

European Commission (2011) Energy efficiency plan. COM/2011/0109 Final, Brussels, p 2

European Commission (2013) Energy challenges and policy. IEA, Brussels, p 19

European Commission (2007) An energy policy for Europe. COM (2007) 1 final, Brussels, p 4

Eurostat (2011) Energy, transport and environment indicators, 2011 edn. Eurostat Pocketbooks, ISSN 1725–4566, p 24

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Energy_production_and_imports

European Commission (2007) An energy policy for Europe. COM (2007) 1 final, Brussels, p 3

Ademe (2012) Energy efficiency trends in buildings in the EU—lessons from the Odyssee Mure project. Available at: http://www.odyssee-mure.eu/publications/br/energy-efficiency-in-buildings.html

Bohne E (2011) Conflicts between national regulatory cultures and EU energy regulations. Elsevier Util Policy J 19:1

European Commission (2009) Report on progress in creating the internal gas and electricity market. COM (2009) 115, p 13

European SmartGrids Technology Platform (2006) Vision and strategy for Europe’s electricity networks of the future. European Commission, Brussels, p 4

European Commission (2011) Smart grid mandate—Standardization mandate to European standardisation organisations (ESOs) to support European smart grid deployment. Brussels, p 3

European Commission (2011) 2009–2010 Report on progress in creating the internal gas and electricity market. Brussels, Ibid, p 10

European Commission (2010) Europe 2020—A strategy for competitive, sustainable and secure energy. COM (2010) 639 final, Brussels

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Energy_introduced

See European Commission (2007) An energy policy for Europe. COM (2007) 1 final, Brussels

See European Commission (2010) Europe 2020 a strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. COM (2010) 2020 final, Brussels

European Commission (2010) Energy 2020 a strategy for competitive, sustainable and secure energy. COM (2010) 639 final, Brussels

European Commission (2011) A resource-efficient Europe—flagship initiative under the Europe 2020 strategy. COM (2011) 21 final, Brussels

European Commission (2011) Energy efficiency plan. COM (2011) 109 final, Brussels

European Commission (2011) Smart grids: from innovation to deployment, COM (2011) 202 final, Brussels

Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 on energy efficiency, amending Directives 2009/125/EC and 2010/30/EU and repealing Directives 2004/8/EC and 2006/32/EC

European Commission (2011) A roadmap for moving to a competitive low carbon economy in 2050. COM (2011) 112 final, Brussels

European Commission (2011) Energy roadmap 2050. COM (2011) 885 final, Brussels

European Commission (2011) A roadmap for moving to a competitive low carbon economy in 2050. COM (2011) 112 final, Brussels, p 5

European Commission (2013) Green paper—a 2030 framework for climate and energy policies. COM (2013) 169 final, Brussels

European Commission (2014) A policy framework for climate and energy in the period from 2020 to 2030. COM (2014) 15 final, Brussels

Directive 2004/8/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 February 2004 on the promotion of cogeneration based on a useful heat demand in the internal energy market and amending Directive 92/42/EEC (2004) OJ L 52:50–60

Directive 2006/32/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2006 on energy end-use efficiency and energy services and repealing Council Directive 93/76/EEC (2006) OJ L 114:64–85. Amended by Regulation (EC) No 1137/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2008

Directive 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources and amending and subsequently repealing Directives 2001/77/EC and 2003/30/EC (2009) OJ L 140:16–62

Directive 2009/72/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity and repealing Directive 2003/54/EC (2009) OJ L 211:55–92

Directive 2010/31/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 May 2010 on the energy performance of buildings (2010) OJ L 153:13–35

http://europa.eu/legislation_summaries/energy/internal_energy_market/index_en.htm

Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on energy efficiency and repealing Directives 2004/08/EC and 2006/32/EC, COM (2011) 370 final, Brussels, 22.6.2011. Explanatory Memorandum, Point 5.1

Bertoldi P (2012) EU energy efficiency policies. Moscow

Directorate general for internal policies policy department a: economic and scientific policy. Effect of smart metering on electricity prices. IP/A/ITRE/NT/2011, 16 February 2012, p 11

European Commission (2013) Energy challenges and policy. Brussels, p 4

See Kotchen M (2006) Green markets and private provision of public goods. J Polit Econ 114(4):816–834

Kotchen M, Moore M (2007) Private provision of environmental public goods: household participation in green-electricity programs. J Environ Econ Manage 53(1):1–16

Directorate General for Internal Policies, Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy—Industry, Research and Energy (2010) Decentralized energy systems. IP/A/ITRE/ST/2009–16, Brussels, p 17

Drucker P (1967) The effective executive: the definitive guide to getting the right things done. HarperBusiness Essentials

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer-Verlag London

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Badea, G.V. (2015). Microgeneration Outlook. In: Badea, N. (eds) Design for Micro-Combined Cooling, Heating and Power Systems. Green Energy and Technology. Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-6254-4_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-6254-4_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-4471-6253-7

Online ISBN: 978-1-4471-6254-4

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)