Abstract

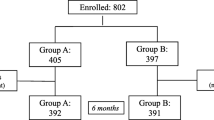

This paper summarizes the objectives, design, follow-up, and data validation of a cluster-randomized trial of a breastfeeding promotion intervention modeled on the WHO/UNICEF Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI). Thirty-four hospitals and their affiliated polyclinics in the Republic of Belarus were randomized to receive BFHI training of medical, midwifery, and nursing staffs (experimental group) or to continue their routine practices (control group). All breastfeeding mother-infant dyads were considered eligible for inclusion in the study if the infant was singleton, bom at 237 weeks gestation, weighed ≥2500 grams at birth, and had a 5-minute Apgar score ≥5, and neither mother nor infant had a medical condition for which breastfeeding was contraindicated. One experimental and one control site refused to accept their randomized allocation and dropped out of the trial. A total of 17,795 mothers were recruited at the 32 remaining sites, and their infants were followed up at 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of age. To our knowledge, this is the largest randomized trial ever undertaken in area of human milk and lactation. Monitoring visits of all experimental and control maternity hospitals and polyclinics were undertaken prior to recruitment and twice more during recruitment and follow-up to ensure compliance with the randomized allocation. Major study outcomes include the occurrence of ≥1 episode of gastrointestinal infection, ≥2 respiratory infections, and the duration of breastfeeding, and are analyzed according to randomized allocation (“intention to treat”). One of the 32 remaining study sites was dropped from the trial because of apparently falsified follow-up data, as suggested by an unrealistically low incidence of infection and unrealistically long duration of breastfeeding, and as confirmed by subsequent data audit of polyclinic charts and interviews with mothers of 64 randomly-selected study infants at the site. Smaller random audits at each of the remaining sites showed extremely high concordance between the PROBIT data forms and both the polyclinic charts and maternal interviews, with no evident difference in under- or over-reporting in experimental vs control sites. Of the 17,046 infants recruited from the 31 participating study sites, 16,491 (96.7%) completed the study and only 555 (3.3%) were lost to follow-up. PROBIT’s results should help inform decision making for clinicians, hospitals, industry, and governments concerning the support, protection, and promotion of breastfeeding.

the Nutrition Unit, World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Preview

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kovar MG, Serdula MG, Marks JS, et al. Review of the epidemiologic evidence for an association between infant feeding and infant health. Pediatrics 1984;74:615–638.

Jason JM, Nieburg P, Marks JS. Mortality and infectious disease associated with infant-feeding practices in developing countries. Pediatrics 1984;74:702–727.

Feachem RG, Koblinsky MA. Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: promotion of breast feeding. Bull WHO 1984;62:271–291.

Kramer MS. Infant feeding, infection, and public health. Pediatrics 1988;81: 164–166.

Howie PW, Forsyth JS, Ogston SA, Clark A, du V Florey C. Protective effect of breast feeding against infection. Br Med J 1990;300:11–16.

Cunningham AS, Jelliffe DB, Jelliffe EFP. Breast-feeding and health in the 1980’s: a global epidemiologic review. J Pediatr 1991;118:659–666.

Beaudry M, Dufour R, Marcoux S. Relation between infant feeding and infections during the first six months of life. J Pediatr 1995;126:191–7.

Dewey KG, Heinig MJ, Nommsen-Rivers LA. Differences in morbidity between breast-fed and formula-fed infants. J Pediatr 1995;126:696–702.

Kramer MS. Does breast feeding help protect against atopic disease? Biology, methodology, and a golden jubilee of controversy. J Pediatr 1988;112:181–190.

Saarinen UM, Backman WA, Kajosaari M, Simes MA. Prolonged breast-feeding as prophylaxis for atopic disease. Lancet 1979;ii:163–166.

Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Beautrais AL, Shannon FT, Taylor B. Eczema and infant diet. Clin Allergy 1981;11:325–331.

Hide DW, Guyer BM. Clinical manifestations of allergy related to breast and cows’s milk feeding. Arch Dis Child 1981;56:172–175.

Kramer MS, Moroz B. Do breast feeding and delayed introduction of solid foods protect against subsequent atopic eczema? J Pediatr 1981;98:546–550.

Taylor B, Wadsworth J, Golding J, Butler N. Breast feeding, eczema, asthma, and hayfever. J Epidemiol Comm Health 1983;37:95–99.

Hill AB: A Short Textbook of Medical Statistics. London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1977, p 27.

Sauls HS. Potential effect of demographic and other variables in studies comparing morbidity of breast-fed and bottle-fed infants. Pediatrics 1979;64:523–527.

Bauchner H, Leventhal JM, Shapiro ED. Studies of breast-feeding and infections: how good is the evidence? JAMA 1986;256:887–892.

Kramer MS. Breast feeding and child health: methodologic issues in epidemiologic research. In: Goldman A, Hanson L, Atkinson S, eds. The Effects of Human Milk Upon the Recipient Infant. New York: Plenum Press, 1987:339–360.

Habicht J-P, DaVanzo J, Butz WP. Does breastfeeding really save lives, or are apparent benefits due to biases? Am J Epidemiol 1986;123:279–290.

Victora CG, Vaughan JP, Lambardi C, Fuchs SMC, Gigante LP, Smith PG, Nobre LC, Teixeira AMB, Moreira LB, Barros FC. Evidence for protection by breast-feeding against infant deaths from infectious diseases in Brazil. Lancet 1987;2:319–322.

Rubin DH, Leventhal JM, Krasilnikoff PA, Kuo HS, Jekel JF, Weile B, Levee A, Kurzon M, Berget A. Relationship between infant feeding and infectious illness: a prospective study of infants during the first year of life. Pediatrics 1990;85:464–471.

American Academy of Pediatrics. The promotion of breast-feeding. Pediatrics 1982;69:654–661.

Kramer MS, Gray-Donald K. Breast feeding promotion: methodologic issues in health services research. Geneva: World Health Organization, Document MCW86.13,1988:21–38.

Birenbaum E, Fuchs C, Reichman B. Demographic factors influencing the initiation of breast-feeding in an Israeli urban population. Pediatrics 1989;83:519–523.

Kistin N, Benton D, Rao S, Sullivan M. Breast-feeding rates among black low-income women: effect of prenatal education. Pediatrics 1990;86:741–746.

WHO/UNICEF. Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding: the special role of maternity services. Geneva: WHO, 1989.

Renfrew MJ, Lang S. Feeding schedules in hospitals for newborn infants. (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 1999. Oxford: Update Software.

Sikorski J, Renfrew MJ. Support for breastfeeding mothers. (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 1999. Oxford: Update Software.

Renfrew MJ, Lang S. Early vs delayed initiation of breastfeeding. (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 1999. Oxford: Update Software.

Renfrew MJ, Lang S. Interventions for improving breastfeeding technique. (Cochrane Review), In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 1999. Oxford: Update Software.

Gray-Donald K, Kramer MS, Munday S, Leduc DG. Effect of formula supplementation in the hospital on the duration of breast feeding: a controlled clinical trial. Pediatrics 1985;75:514–518.

Gray-Donald K, Kramer MS. Causality inference in observational vs experimental studies: an empirical comparison. Am J Epidemiol 1988;27:885–892.

Cronenwett L, Stukel T, Kearney M, Barrett J, Covington C, Del Monte K, Reindhardt R, Rippe L. Single daily bottle use in the early weeks postpartum and breastfeeding outcomes. Pediatrics 1992;90:760–766.

McBryde A, Durham NC. Compulsory rooming-in the ward and private newborn service at Duke Hospital. JAMA 1951;145:625–627.

Jackson EB, Wilkin LC, Auerbach H. Statistical report on incidence and duration of breastfeeding in relation to personal social and hospital maternity factors. Pediatrics 36.1956;17:700–713.

Cole JP. Breast-feeding in the Boston suburbs in relation to personal-social factors. Clin Pediatr 1977;37:89–94.

Starling J, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Taylor B. Breast-feeding success and failure. Aust Paediatr J 1979;15:271–274.

Verronen P, Visakorpi JK, Lammi A, Saarikoski S, Tamminen T. Promotion of breast feeding: effect on neonates of change of feeding routine at a maternity unit. Acta Paediatr Scand 1980;69:279–282.

World Health Organization. Contemporary Patterns of Breast-feeding: Report of the WHO Collaborative Study on Breast-feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO), 1981.

Bloom K, Goldbloom RB, Robinson SC, Stevens FE. II. Factors affecting the continuance of breast-feeding. Acta Paediatr Scand 1982;300 (Suppl):9–14.

Richard L, Alade MO. Sucking technique and its effect on success of breastfeeding. Birth 1992;19:185–189.

Victora CG, Tomasi E, Olinto MTA, Barros FC. Use of pacifiers and breastfeeding duration. Lancet 1993;341:404–406.

Barros FC, Victora CG, Semer TC, Filho ST, Tomasi E, Weiderpass E. Use of pacifiers is associated with decreased breastfeeding duration. Pediatrics 1995;95:497–499.

Gale CR, Martyn CN. Dummies and the health of Hertfordshire infants, 1911–1930. Soc Social Hist Med 1995;8:231–255.

World Health Organization. Indicators for assessing breast-feeding practices. WHO Document WHO/CDD/SER/9 1.14. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1991.

Shipley MJ, Smith PG, Dramaix M. Calculation of power for matched pair studies when randomization is by group. Int J Epidemiol 1989;18:457–461.

Gail MH, Byar DP, Pechacek TF, Corle DK. Aspects of statistical design for the community intervention trial for smoking cessation (COMMIT). Cont Clin Trials 1992;13:6–21.

Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical Methods, 6th ed. Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1967,p 311.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2002 Kluwer Academic Publishers

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kramer, M.S. et al. (2002). Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (Probot): A Cluster-Randomized Trial in the Republic of Belarus. In: Koletzko, B., Michaelsen, K.F., Hernell, O. (eds) Short and Long Term Effects of Breast Feeding on Child Health. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 478. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-46830-1_28

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-46830-1_28

Publisher Name: Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN: 978-0-306-46405-8

Online ISBN: 978-0-306-46830-8

eBook Packages: Springer Book Archive