Abstract

Objective

To assess the direct costs involved in treatment of children receiving intensive care in a university-affiliated teaching hospital and its associated implications on the children’s families, in rural India.

Methods

It was a prospective observational study for cost-analysis using questionnaire based interviews and billing records data collection for admissions to the PICU over 27 consecutive months (January 2010 through March 2012).

Results

A total of 784 children were admitted to the unit during the assessment period. Full details of 633 children were included for analysis. The average length of stay was 6.16 d, average hospital expenditure was US$185.67, average hospital expenses per day was US$44.00, average pharmacy expenditure was US$109.67 and average pharmacy expenditure per day was US$20.62 per patient. Children who were ventilated had approximately 61 % more expense per day as compared to non-ventilated ones. Boys and those with health insurance reported higher length of stay. Linear hierarchical regression with backward LR model showed that mechanical ventilation, multiple organ dysfunction, length of stay and insurance cover were the variables significantly affecting the final expenses.

Conclusions

There is a high direct expenditure incurred by families of children receiving intensive care when seen in perspective of high rates of extreme poverty in rural India. These high expenditures make critical care unaffordable to majority of the population lacking insurance cover in resource limited regions with limited universal health coverage, which ultimately leads to suboptimal care and high childhood mortality. It is highly imperative for the governments and global health organizations to be sensitive towards this issue and to plan strategies for the same across different nations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pediatric Critical Care sub-specialty has grown in last two decades in India [1]. Critical care is associated with very high expenses globally and has significant impacts on financial dynamics of the family [2–4]. There is scant literature on the expenditure associated with the utilization of intensive care, and its financial burden on families of children receiving such care in India. In developing countries like India where there is negligible health insurance and governmental health care is non-existent in most rural areas or is of poor quality, the burden of out-of-pocket healthcare expenses amount to a huge portion of average total family income of a middle class family, oftentimes pushing them below the poverty line [5, 6]. In such a setting it is imperative to have data related to healthcare expenses. Poor record maintenance of cost incurred in health facilities and non-sharing of data by private health facilities have resulted in a vacuum of information in this area.

Economic analysis of healthcare provision and its utilization provides insight regarding the magnitude of existent problems, and its financial impact on communities, thus providing information for decision-making, and budgetary resource allocation. Economic analysis is an integral part of effectiveness evaluation and should be a constant exercise to monitor response to the ongoing interventions [7].

There is little data regarding the economic analysis of the children receiving critical care. There are few studies from developed nations which concentrate on individual diseases [8–10] and few on specific interventions [11, 12]. The present study estimates the direct costs of children receiving intensive care in a PICU in university- affiliated private teaching hospital in rural India.

Material and Methods

The authors conducted a prospective observational study covering all patients (age group: 1 mo to 18 y) admitted to Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) for 27 consecutive months (January 2010 through March 2012) at Shree Krishna Hospital, a 550 bed tertiary care multi-specialty rural, university affiliated teaching hospital in Karamsad, Gujarat, India. This hospital is a trust run, not-for-profit organization. The PICU is a tertiary level multidisciplinary unit receiving admissions from across the state. The major referral base is from Anand district and surrounding rural areas. Majority of the patients seeking care in the hospital belong to poor socioeconomic and education levels. The clinicians who are in-charge of the unit have been trained in intensive care. The PICU is a training site in intensive care for residents. Supervised protocol based care is provided to the patients admitted to the unit. The unit is evidence based protocol driven; medical and nursing decisions in the unit are based on these protocols. All concerned staff and trainees are educated about the unit protocol by ongoing seminars, updates and reference materials. The hospital has a policy of admitting every patient presenting at the emergency department and provide care for the period of initial 24 h after which the relatives are explained about the further course and the cost involved according to the disease severity.

As per authors’ observations based on providing care since past several years, the relatives of the patient who cannot afford the treatment, in most cases decide to discontinue with treatment and are discharged because of economic reasons. Economic support (partial or total) is provided on case-to-case basis, considering prognosis, total duration of treatment, estimated cost of treatment, and parental wishes. There is interdisciplinary discussion between the PICU and other concerned speciality staff with the social workers to determine further expected cost and duration of treatment. This is followed by discussion with the family about the same to determine extent of financial support. The final decision on continuation of care is left for the family to decide with social work department and counseling as required. As a hospital policy, for those patients who continue to stay, all are given treatment as required per protocol, and there is no withholding of any treatment based on patient affordability throughout the hospital stay.

For the index study, a questionnaire to capture the clinical and general profile of children being admitted in PICU was designed, and was accepted after in-depth discussions by staff and investigators before beginning the study. The questionnaire was finalized after multiple meetings and discussions to arrive at a common accepted questionnaire; the questionnaire consisted of demographic details, variables relevant to status of the patient at admission and clinical follow-up until discharge. The questionnaire was in English, as it was physician administered. The questions around expenditure asked to the patients were translated in simple vernacular language if needed by the administrator; this data was also double checked for inaccuracies from the hospital billing records. The profiles of the admitted children using the questionnaire were noted at the time of admission in PICU by one of the investigating team members. The observations were conducted through personal interview with the parents of children at the time of admission to PICU within the first 24 h of admission and they were later followed up for further data collection until discharge. The interventions done at the emergency care department and the PICU were recorded.

Data on costs associated with hospitalization (including PICU), and pharmacy expenses, by the family and any concessions provided by the hospital were collected. The cost of treatment per day, and pharmacy expenses per day were calculated. Insurance coverage for the children was noted as being insured or uninsured. For the index study the authors included those with below poverty line (BPL) cards as insured, as they receive healthcare benefits through Government Sponsored Health Insurance Schemes (GSHIS) or receive partial coverage of expenses. The hospital has built-in a systemic subsidy into its computerized billing system, and this being standardized is not modifiable by any hospital personnel.

The authors recorded treatment outcome of the patients at the time of discharge, and classified them according to the body systems involved and major disease groups. Efforts were made to collect maximal possible data for all the study participants.

Descriptive statistics [frequencies and proportions, mean < standard deviation (SD) > as applicable] were used for baseline data analysis. Associations were calculated between relevant parameters using chi square test. The data was entered into MS-Excel and analyzed using SPSS version 14. The costs were presented as quantitative variables such as Average Length of Stay (ALOS), Average Hospital Expenditure (AHE), Average Hospital Expenditure per day (AHED), Average Pharmacy Expenditure (APE), and Average Pharmacy Expenditure per Day (APED). The authors used a conversion rate of 1US $ equal to Indian Rupee 44 according to the rates prevalent for March–April 2011, the period being the median study period [13].

A study focusing on the Pediatric Index of Mortality-2 (PIM2) score and outcome correlation was published earlier [14]; the participants from that study although focusing on different study periods (January 2010 to December 2011) are partially included in the current study for the cost analysis. The questionnaires for both studies were different, but were administered simultaneously in the participants included in both studies.

The study was approved by the HREC (Human Research Ethics Committee) of the institute with waiver of informed consent.

Results

A total of 784 admissions to the unit over 27 consecutive mo were considered for the study. All except 2 participants were followed up prospectively; the 2 patients who were lost to follow up were because of absconsion. Around 149 records had to be excluded from analysis due to incomplete information on important variables. Thus for index study 633 (250 girls, 383 boys) admissions were analyzed, out of which 428(68 %) were discharged, 47(7 %) had died and 158(25 %) were discharged for economic reasons.

The details of the admitted children are shown in Table 1. Most children were in the age group 6–12 y followed by 2–6 y group. Male children were in majority (61 %) in comparison with female children, and also had substantial health insurance coverage. However, an equal percentage of male and female children being discharged for economic reasons was noticed.

In terms of clinical characteristics, 35 % of children admitted in PICU required mechanical ventilation during their course of treatment, followed by children with shock (33 %). Few children admitted had meningitis (18 %) and multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) (11 %); all these categories comparably having both the genders (p > 0.05).

But there was statistically significant association observed in the children requiring ventilator support and they having meningitis/MODS/Shock (Table 2).

Male children had a comparable ALOS at 6.4(SD 5.57) d against 5.8(SD 4.53) d in female children (p = 0.159). The mean(SD) of overall ALOS was 6.16(5.19); ALOS was defined as the ratio of total inpatient days and total admissions. Those having insurance had a mean(SD) ALOS of 6.95(6.16) which was comparable to the not insured [5.94(4.86)]. There was no difference observed in the mean(SD) ALOS in children requiring ventilator [5.96(5.33)] or otherwise [6.28(5.12)]. Same way, ALOS was comparable across children suffering from MODS, shock, needing ventilator support or otherwise. The various age groups also had comparable ALOS but there was statistically significant difference observed in the ALOS for various patient outcomes (discharged for economic reasons, death or discharge) with discharge having maximum mean(SD) ALOS [7.18(5.36)] (p = 0.0001).

Children with MODS reported highest average total expenses (Table 3), followed by patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Children requiring mechanical ventilation reported additional costs at around 61 % in comparison with children not requiring ventilation during their admission in the PICU. Surprisingly, children covered with health insurance showed lower average expenditure compared to non-insured children, however the difference was not substantial.

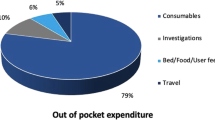

Children in the age group 2–6 y incurred the highest expenses in comparison to children in other age-groups (Table 4). The costs related to hospitalization, pharmacy and concession contributed to 62 %, 22 %, and 16 % of the overall costs across all age categories.

The authors conducted a linear hierarchical regression with backward LR method with total expenditure incurred on treating the children in PICU as the dependent variable and age and sex of the child, PIM2 score, anemia, shock, pneumonia, MODS, meningitis, ventilator, need for central venous line, insurance status, patient outcome, pharmacy expenses, hospital expense and the length of stay in hospital as the independent variables (Table 5). The beta regression coefficients and their respective 95 % confidence intervals (CI) along with predictors that were found to be significant at the end of the linear regression model by backward LR method are shown in Table 5. All tolerance values exceeded 0.1; likewise the variance inflation factor values were also well below the threshold mark of 10. These results indicate that the interpretation of regression coefficients is not affected by multi-co-linearity. The multivariate analysis included the entire sample of patients and the model fitted the data well (R2 = 0.927, F = 884.65, P < 0.0001).

The predictors that weighed most highly on total cost were total pharmacy expense, total hospital expense, length of stay, ventilation, insurance and patients with MODS.

Discussion

In the present study, the direct costs incurred by children admitted in PICU were substantial when compared to average annual income of an Indian household. Overall patients in age group 2–6 y and those with more critical illness had greater expenses (Tables 3 and 4). Intensive care life support interventions like mechanical ventilation had 61 % additional expenditure over those not requiring ventilation. The ventilator charges, the charges of the multi-parameter monitoring and laboratory testing involved in treating the critically ill child were the main contributors to increasing expenditures (Table 5), as seen in other studies [2, 15–17].

Expenses in patients who had died were significantly higher as compared to those who were discharged (Table 3). This could be explained by the fact that patients who had more critical illness required higher degree of life support interventions such as mechanical ventilation and ultimately had more expenses (Tables 4 and 5), as reported in other studies [2].

In the index study, children with medical conditions such as requiring mechanical ventilation, meningitis, MODS and shock reported lower ALOS compared to their non-affected counterparts. Although the difference was not statistically significant, this finding could be attributed to higher rates for discharge for economic reasons/ death in these subgroups.

To the best of authors’ knowledge, this is the first study in a developing country to focus on the costs of treating children in PICU. Similar other studies [18–20] conducted in India have been done on babies admitted in NICUs. Published international studies on treatment costs in PICU have been done in developed countries, and their focus was either on individual diseases [8–10] or on specific interventions [11, 12]. The present study shows that the average cost of treatment of children admitted in PICU in a rural teaching hospital in Gujarat, India is US $361.74 (Rs. 15,555) When compared against per capita national income during 2010–11, this expenditure stands at 30 % of the annual income [21].

The recent 12th Five-Year Plan does emphasize the Univeral Health Coverage (UHC) policy for India and is aimed to meet the healthcare needs of its population through a publicly financed system. However, along with the healthcare provision, the price of the provision of such services also needs to be documented. The present study precisely set out to do this. The evidence on costs and provision of pediatric care as documented in index study could be used by the National Health Regulatory Development Authority (NHRDA), an independent national body linked to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW), proposed in the UHC High Level Expert Group.

The current study has several strengths; foremost being adequate sample size and extended period of assessment. Any bias due to incorrect description by the family members was reconfirmed by hospital billing data by the time of data collection. The index study could capture accurate data and outcomes of the sample children as a trained pediatric resident, who was familiar with the admission, billing and discharge process of the hospital, collected the data.

A single center based study can be considered a limitation, but authors feel similar issues would be prevalent in comparable rural and semi urban areas of India. It is suggested that similar studies across various PICU facilities (both private and public) are warranted. The authors did not calculate the indirect costs (such as travel costs, and loss of wages) of caregivers for managing the admitted children. But if they were calculated they would further elaborate on how intensive care provision expenses are unbearable for most of the middle and lower income class families. The significant contribution of indirect expenses to the total expenses borne by families of children under 10 y of age hospitalized in a PICU has been studied in detail by other authors [22]. The authors also did not look at the actual costs and profit margins of the hospitals, but focused only on the hospital expenditure borne by the families of the children.

Conclusions

This study even with its limitations does emphasize the need for urgent implementation of universal health coverage for improving access to critical care services for children across resource limited regions of the world. Given that less than 2 % of the population of India has full insurance coverage and only 15 % of population has partial government sponsored coverage [23]; costs for treating children in PICU in India are substantial for majority of the poor and rural population. These expenses borne by the families should be viewed in the context of extreme poverty of more than 400 million Indians who live on less than $1.25 (PPP) per day [6] and the extremely high inflation rates [24].

References

J Pediatr Crit Care, Home page - About the journal. Available at: http://www.journalofpediatriccriticalcare.com/. Accessed on 15th January 2016.

Dasta JF, McLaughlin TP, Mody SH, Piech CT. Daily cost of an intensive care unit day: the contribution of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1266–71.

Cohen IL, Chalfin DB. Economics of mechanical ventilation: surviving the 90’s. Clin Pulm Med. 1994;1:100–7.

Heffler S, Smith S, Keehan S, Clemens MK, Won G, Zezza M. Health spending projections for 2002–2012. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003; Suppl Web Exclusives:W3–54–65.

Shahrawat R, Rao KD. Insured yet vulnerable: out-of-pocket payments and India’s poor. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27:213–21.

Poverty reduction and equity (2010). World Bank, 2012. Available at: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTPOVERTY/0,,menuPK:336998~pagePK:149018~piPK:149093~theSitePK:336992,00.html. Assessed on 11 September 2012.

Gillian C, Sarah C, Terry K. Evidence-based decision-making in child health: the role of clinical research and economic evaluation. In: Wendy U, editor. Economic evaluation in child health. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 255–70.

Donald SS, Jose AS. Economic evaluation of dengue prevention. In: Wendy U, editor. Economic evaluation in child health. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 225–37.

Jonathan DC, Sean DS. Economic evaluations in the management of pediatric asthma. In: Wendy U, editor. Economic evaluation in child health. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 197–209.

Tilford JM, Ali IR. Is more aggressive treatment of pediatric traumatic brain injury worth it. In: Wendy U, editor. Economic evaluation in child health. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 181–96.

Scott DG. Economic evaluations of newborn screening. In: Wendy U, editor. Economic evaluation in child health. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 113–32.

Damian GW, Philippe B, Raymond H. Economic evaluation of childhood vaccines. In: Wendy U, editor. Economic evaluation in child health. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 211–23.

XE Currency Charts (USD/INR), XE.com INC. Available at: http://www.xe.com/currencycharts/?from=USD&to=INR&view=10Y. Assessed on 22 May 2015.

Shukla VV, Nimbalkar SM, Phatak AG, Ganjiwale JD. Critical analysis of PIM2 score applicability in a tertiary care PICU in western India. Int J Pediatr. 2014;2014:703942.

Kanter RK. Post-intensive care unit pediatric hospital stay and estimated costs. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:220–3.

Rapoport J, Teres D, Zhao Y, Lemeshow S. Length of stay data as a guide to hospital economic performance for ICU patients. Med Care. 2003;41:386–97.

Jacobs P, Edbrooke D, Hibbert C, Fassbender K, Corcoran M. Descriptive patient data as an explanation for the variation in average daily costs in intensive care. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:643–7.

Narang A, Kiran PSS, Kumar P. Cost of neonatal intensive care in a tertiary care center. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42:989–97.

Venkatnarayan K, Sankar JM, Deorari A, Krishnan A, Paul VK. A micro-costing model of neonatal intensive care from a tertiary Indian unit: feasibility and implications for insurance. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:215–7.

Paul VK, Kannaraj V, Gupta S, Sarma RK. Cost of neonatal intensive care in a tertiary care hospital in New Delhi (India). Pediatr Res. 1997;41:208.

Per capita income in 2010–11 at Rs 54, 835. The Economic times indicators, 2011. Available at: http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2011-05-31/news/29604458_1_capita-income-national-income-economy-at-current-prices. Accessed on 14 May 2015.

Wasserfallen JB, Bossuat C, Perrin E, Cotting J. Cost borne by families of children hospitalized in a pediatric intensive care unit: a pilot study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136:800–4.

Mehra P. Only 17 % have health insurance cover. Available at: http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/only-17-have-health-insurance-cover/article6713952.ece. Accessed on 14 May 2015.

World Bank. World development indicators, inflation and consumer prices (annual %). Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FP.CPI.TOTL.ZG/countries/1W-IN?display=graph. Assessed on 22 May, 2015.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank the participants for participation and the hospital staff for all their support in acquiring the data.

Contributions

VVS: Conceptualized the study, collected data, helped in analysis, wrote the paper and approved the final manuscript; SMN: Designed the study, helped in data collection, gave critical inputs in analysis and interpretation, wrote the paper and approved the final manuscript; JDG: Analyzed the data, wrote the results and interpretation of the paper, approved the final manuscript; DJ: Helped in data analysis, wrote the paper and approved the final manuscript. SMN will act as guarantor for the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

None.

Source of Funding

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shukla, V.V., Nimbalkar, S.M., Ganjiwale, J.D. et al. Direct Cost of Critical Illness Associated Healthcare Expenditures among Children Admitted in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit in Rural India. Indian J Pediatr 83, 1065–1070 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-016-2165-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-016-2165-4