Abstract

The existence of a bubble in the vicinity of an elastic boundary appears in many situations such as medical and mechanical systems. On the other hand, bubble collapse is considered a source of energy loss in most systems and caused a lot of damages to it. This research is the first attempt to prevent bubble collapse in the vicinity of an elastic boundary by using control algorithms. In this paper, first, the nonlinear dynamic model of bubble in the vicinity of an elastic wall is introduced and then rewritten into state-space form. The second part of this paper is devoted to the design of the sliding mode controller for the bubble system, where the ultrasonic pressure plays the role of control input and the output is the bubble radius. Our main objective is to design a stabilizing controller that is able to regulate the radius of the bubble to the desired radius. At first, traditional sliding mode controller is proposed. Despite the successful tracking error, the chattering problem of this method leads us to introduce the boundary layer sliding mode control. Although the chattering phenomenon has been attenuated, it increases the steady-state error. Finally, robust integral sliding mode control is suggested to minimize the steady-state error while the chattering problem is removed. Numerical simulations including the case of parametric uncertainty are also presented. The results of this study are of immediate interest for medical applications such as ultrasound imaging and also industrial applications such as designing long-lasting pumps and valves.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Lord Rayleigh was the first one who analyzed the dynamic of a spherical bubble surrounded by liquid. He ignored surface viscosity, tension, compressibility and considered a bubble full of gas. Additional attempts by Plesset lead to the Rayleigh–Plesset equation, the simplest equation to describe the bubble’s radial behavior [1]. In continuation, Keller presented the Rayleigh–Plesset–Keller equation which is the time evolution of a single and spherical bubble [2].

Recently, a comprehensive investigation into the dynamic of bubble near different types of boundaries has been carried out [3, 4]. There are different versions of the Rayleigh–Plesset equation that study the radial behavior of an encapsulated microbubble under different conditions. In [5], Doinikov attempted to model an encapsulated microbubble in the vicinity of a rigid wall by a modified version of Rayleigh–Plesset equation. In [6, 7], authors explained the bubble behavior under different conditions such as near a fluid layer and elastic wall with mathematical language. However, they ignored the fact that in the actual world contrast agent microbubble oscillates in the vicinity of a boundary layer [8]. Two modified Rayleigh–Plesset equations also describe the governing dynamics and the secondary Bjerknes force between two bubbles [9].The bubble radial behavior changes significantly in the presence of a boundary layer.

In [10], the authors reported that the scattered pressure of an encapsulated microbubble was influenced by the boundary layer such as an elastic wall. Similarly in [11], experimental studies show that bubble’s proximity to the boundary layer caused noticeable changes in the radius- time curve of bubble, Lankford experimental observation also confirms that the acoustic signal of the contrast agent microbubble is reduced due to its proximity to the rigid wall [12]. Garbin observed more than 50% reduction in the oscillation amplitude of an encapsulated microbubble due to the presence of the boundary layer [13].

Recently, encapsulated microbubble is widely used in modern medicine because it can pass through the narrowest vessels in the body when it is administrated to the circulatory system. Encapsulated microbubble is considered a novel method for transporting and releasing drugs to the desired location [14, 15]. Vibration of microbubble produces a local pulsating disturbance in the surrounding liquid and this property helps to blood–brain barrier opening [16]. Encapsulated microbubbles are also employed as an ultrasound contrast agent for clinical diagnosis in cardiology to improve the detection and characterization of tumors [17]. Nonlinear oscillation is generated, when microbubble is exposed to a typical acoustic field. This emission signal contains higher harmonics which can be distinguished from the primary ultrasound [18]. This property is employed in the ultrasound radiography application ranges from stroke detection to blood volume and perfusion measurement [19, 20].

The results of this study are also useful for industrial design. Control valves and pumps are vital components in industrial applications. The useful life of industrial valves and pumps are highly affected by the phenomenon of bubble collapse [21, 22]. In [23], the authors investigate the effect of the number of trims on the performance of the globe valve and how it suppresses the cavitation problem. It should be mentioned that most of the proposed methods are not economically justified and demand to change the mechanical structure of valves and pumps. This paper suggests a novel solution to prevent from bubble collapse and efficient method to extend the life of industrial valves.

Recently, sliding mode control (SMC) was turned into a popular method by robustness and simple implementation and applied to a variety of systems [24]. The main negative aspect of SMC control is a chattering phenomenon [25]. This phenomenon is extremely damaging to the actuators of the physical system [26]. In order to prevent chattering in SMC, Slotine proposed quasi-SMC, which considered a boundary layer for the sliding manifold [27]. The main drawback of the proposed method is to increase the tracking error of the state vector, which in many cases is undesirable. In [28], integral sliding mode control (ISMC) is introduced which improves both tracking error and chattering problem.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 contain model description including governing equation and also control challenges. Section 3 introduces various sliding mode control schemes and checking the stability of the proposed sliding manifold via the Lyapunov theory. Simulation results and analysis of their performances including the case of uncertain initial bubble radius and liquid viscosity are also presented.

2 Model description

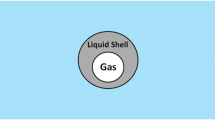

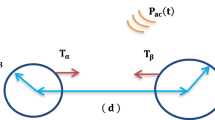

The governing dynamic of encapsulated microbubble is achieved by using the image sources method and Lagrangian formula [29, 30]. As shown in Fig. 1, in the image sources method, a virtual bubble is considered on the right side of the real bubble instead of wall. The governing dynamic of encapsulated microbubble in the vicinity of an elastic wall is described by the nonlinear second-order differential equation known as Rayleigh–Plesset-like equation as follows [31];

where \(R,\dot{R}{\text{ and S}}\) describe microbubble radius, interface velocity of microbubble and the effect of encapsulation, respectively. De Jong mathematically models the effect of encapsulation as follows [32];

The equilibrium gas pressure \(\left( {P_{G0} } \right)\) inside the microbubble in the vicinity of an elastic wall is introduced as follows;

The parameters used in Eqs. 1–3 are completely introduced in Table 1. The first step for employing control algorithms into nonlinear dynamic of encapsulated microbubble in the vicinity of an elastic wall is rewriting the Eq. (1) into state-space form. For this purpose, the vector \(X = \left[ {x_{1} \, x_{2} } \right]^{T} = \left[ {R \, \dot{R}} \right]^{T}\) is considered as the state vector.

According to this consideration, the equivalent state-space form of Eq. (1) is obtained as follows:

where \(\left( {u\left( t \right) = P_{0} + P_{ac} } \right)\) and \(\left( {y = x_{1} = R} \right)\) are considered to be control input signal i.e. acoustic pressure wave and the output of the system, respectively. The system presented in (4) can be simplified into affine form as follows;

The terms \(f\left( X \right)\) and \(g\left( X \right)\) in system (5) are nonlinear and differentiable functions as follows;

Remark 1

The distance between wall and microbubble is in order of bubble size; therefore, time delays problem is negligible for sound wave propagation between wall and bubble [33].

Remark 2

The term \(\rho_{L} \tau \left( \varepsilon \right)\) in Eq. (1) determines the effective density. The term \(\tau \left( \varepsilon \right)\) is a dimensionless factor that depends on the wall’s mechanical properties. In other words, the material of considered wall has direct effect on the behavior of designated microbubble.

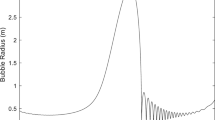

Both experimental and theoretical research emphasizes that bubble’s radial behavior enormously changes in the presence of a boundary layer. In [13], Garbin published his experimental observations on changes in the amplitude of oscillation caused by wall presence. He assumed that a single bubble with initial radius \(R_{0} = 2\;\upmu{\text{m}}\) is derived with the acoustic pressure wave as follows;

where \(P_{m} = 200\;{\text{KPa}}\) is the pressure amplitude,\(f = 2.45{\text{ MHz}}\) is the center frequency and \(N = 10\) is the number of acoustic cycles. According to Fig. 2, the radius-time curve shows more than 50% reduction in amplitude oscillation of the bubble due to the presence of wall.

Experimental comparison of radius-time curves for an encapsulated MB surrounded by liquid (No wall), in the vicinity of wall (No contact), attached to wall (Contact) [31]

Theoretical analysis of the bubble’s radial behavior confirmed the experimental results. This analysis was based on Eq. (1) and parameters presented in Table 1 for three different conditions. First, the bubble is oscillating far away from the wall and surrounded by liquid. Second, the bubble is attached to the wall and finally, the bubble is in the vicinity of the wall but no contact between wall and bubble is established. The bubble is insonified with the same condition as experimental observation. According to Fig. 3, the oscillation amplitude of the bubble in the vicinity of the wall is reduced more than 60% and it has higher frequency than bubble surrounded by liquid.

Theoretical comparison of radius-time curves for an encapsulated MB surrounded by liquid (No wall), in the vicinity of wall (No contact), attached to the wall (Contact) [31]

Both experimental and theoretical results confirmed that microbubble in the vicinity of an elastic wall presents radial oscillation with lower amplitude but higher frequency than bubble surrounded by liquid. In this paper, we intend to use nonlinear control algorithm in order to take the radial oscillation of microbubble under control. In the other word, our main control objective is that bubble follow the desired radius by applying control input signal i.e. acoustic pressure wave.

One of the important advantages of this research is in the field of ultrasonic target imaging. In ultrasonic target imaging, distinguishing the scattered pressure of designated microbubble from other circulating microbubbles is a crucial task. The scatter pressure generated by encapsulated microbubble in far-field zone, i.e., for \(r_{1} \gg R\) is given by [7];

This equation relies heavily on the bubble radius and its derivatives. Different harmonics in the Fourier spectrum of scatter pressure are observed due to the pulsating behavior of the designated bubble, which makes it difficult to distinguish the scattered pressure from other agents. The nonlinear control scheme presented in this paper prevents from pulsating behavior and makes it easy to distinguish the scattered pressure.

3 Controller design

In this section, the procedure of designing a sliding mode controller is discussed. Our main control objective is to obtain a stabilizing control input signal \(\left( {u\left( t \right)} \right)\) which is able to regulate the radius of the bubble \(\left( {x_{1} \left( t \right)} \right)\) into the desired radius \(\left( {x_{d} \left( t \right)} \right)\). The stabilization of the bubble dynamic is guaranteed by using the Lyapunov stability analysis theory.

The design of the sliding mode controller starts by defining the error in the system (5) as follows;

where \(x_{d} \left( t \right)\) is the desired reference radius.

The most significant step in the process of designing a sliding mode controller is determination of sliding manifold. Since the nonlinear dynamic of a microbubble in the vicinity of an elastic wall (5) has a relative degree of two, the sliding manifold is defined as follows;

The sliding mode controller design is consists of two phases. In the first phase, the system states \(X = \left[ {x_{1} \, x_{2} } \right]^{T}\) move from initial states \(\left( {X\left( 0 \right)} \right)\) toward the sliding manifold \(\left( {S_{Tra} \left( X \right)} \right)\) in the phase plane \(\left( {x_{1} - x_{2} {\text{ plane}}} \right)\) under equivalent control law \(\left( {u_{equ} \left( t \right)} \right)\). In the second phase, the switching control law \(\left( {u_{sw} \left( t \right)} \right)\) is applied to transfer system states along the sliding manifold (10) to the desired point \(\left( {x_{d} \left( t \right)} \right)\). The equivalent control law \(\left( {u_{equ} \left( t \right)} \right)\) is achieved by checking the invariance condition \(\left( {\dot{S}_{Tra} \left( X \right) = 0} \right)\) as follows;

Substituting from (5) into (11) yields;

Theorem 1

For the nonlinear system of encapsulated microbubble in the vicinity of an elastic wall (5), the tracking error (9) exponentially converges to zero if the following control law holds;

where \(\left( {K_{1} > 0} \right)\) is a design constant.

Proof

Positive-definite Lyapunov candidate function is considered as follows;

Taking its derivative with along the time yields;

According to the Lyapunov theory, the main task of a control input signal (13) is making \(\left( {\dot{V}\left( X \right)} \right)\) negative definite. Substituting Eq. (13) into Eq. (15) yields:

It is obvious that \(\left( {\dot{V}\left( X \right)} \right)\) is negative definite function if a positive value is selected for the gain \(\left( {K_{1} } \right)\). According to the Lyapunov theory, the sliding manifold (10) is asymptotically stable and tracking error (9) exponentially converges to zero. The proof is completed.□

It should be noted that oftentimes the parameters like liquid viscosity and initial radius are uncertain in the dynamic of microbubble in the vicinity of an elastic wall [34]. In this case, the estimated dynamic \(\left( {\hat{f}\left( X \right)} \right)\) should be replaced instead of \(\left( {f\left( X \right)} \right)\) in Eq. (13).We assume that the estimated error \(\left| {f\left( X \right) - \hat{f}\left( X \right)} \right|\) is bounded by some known function as \(F = F\left( {x,\dot{x}} \right)\), i.e. \(\left| {\hat{f}\left( X \right) - f\left( X \right)} \right| < F\).

Theorem 2

Tracking error (9) converges to zero and the chattering phenomenon is optimally minimized if the gain \(\left( {K_{1} } \right)\) is selected as \(K_{1} = F + \eta ,\eta > 0\)

Proof

The reachability condition is considered as follows;

Taking its derivative with respect to time yields:

Substituting Eq. (13) into Eq. (18) yields;

By simplifying Eq. (19) and substituting \(\text{sgn} \left( {S_{Tra} \left( X \right)} \right)\) with \(\frac{{\left| {S_{Tra} \left( X \right)} \right|}}{{S_{Tra} \left( X \right)}}\) yields;

It is understood from Eq. (20) that the optimal choice for the gain \(\left( {K_{1} } \right)\) is as follows;

Since all actuators in the actual world have the control bounds, we propose the following constraint;

Here \(u_{\rm{max} }\) is the maximum value of the control input signal.

The system states reaches the sliding manifold \(\left( {S_{Tra} \left( X \right) = 0} \right)\) in a finite time \(\left( {t_{r} } \right)\). This time is calculated by integrating the reachability condition of Eq. (17) between \(t = 0\) and \(t = t_{r}\) as follows;

One solution to reduce the chattering magnitude is to use saturation function instead of sign function in the control input signal (13) as follows;

where \(\phi\) is the thickness of the boundary layer around the sliding manifold. This reduction in the chattering magnitude caused by the interpolation of the sliding manifold \(\left( {S_{Tra} \left( X \right)} \right)\) in a thin layer of thickness \(\phi\), but its main drawback is increasing steady-state error.

The main benefit of integral sliding manifold control over the boundary layer and traditional sliding manifold is the elimination of chattering problem and the improvement of the steady-state error [35]. In this novel solution, the integral sliding manifold is suggested as follows;

where \(\left( {\lambda_{1} ,\lambda_{2} > 0} \right)\) are design constants.

Theorem 3

For the nonlinear system of encapsulated microbubble in the vicinity of an elastic wall (5), according to the reachability law condition of Eq. (17), the bubble radius will converge asymptotically to the desired radius and stay there forever if the sliding manifold is selected as Eq. (25) and the control input signal is adopted as follows;

where \(\left( {K_{2} > 0} \right)\) is a design constant.

Proof

The sliding manifold \(\left( {S_{ISMC} \left( X \right)} \right)\) is considered outside of the boundary layer (24), hence, the Eq. (26) can be rewritten as follows;

Positive-definite Lyapunov candidate function is considered as follows;

Taking its derivative with respect to time yields:

Substituting from Eq. (9) into Eq. (29) yields;

The main objective of the control input signal (27) is making \(\dot{V}\left( x \right)\) negative definite which leads to asymptotically stabilization of integral sliding manifold. Substituting Eq. (26) into Eq. (30) yields;

According to the Lyapunov theory and reachability condition (17), Eq. (31) states that integral sliding manifold (25) is asymptotically stable. In other words, the tracking error (9) is converged exponentially to zero within the finite time and the chattering problem is minimized simultaneously. In the integral sliding mode control solution, the reaching time from initial states to the boundary layer is calculated by integrating the reachability condition (17) between \(t = 0\) and \(t = t_{r}\) as follows;

Remark 3

by a simple comparison between Eqs. (23) and (32), it is understood that using integral sliding manifold leads to faster reaching time than the traditional sliding manifold.

Remark 4

the thickness of the boundary layer \(\left( \phi \right)\) in the saturation function of Eq. (24) has a direct relationship with the faster reaching time (32) and attenuation of chattering magnitude but has a reverse relationship with steady-state error (9).

Corollary 1

with regards to Eq. (22), in a saturated condition \(\left( {\left| {u\left( t \right)} \right| \ge u_{\hbox{max} } } \right)\), the control input signal of Eq. (26) acts like a conventional PID controller with coefficients of \(K_{p} = \frac{{\lambda_{1} }}{\phi },K_{I} = \frac{{\lambda_{2} }}{\phi },K_{d} = \frac{1}{\phi }\)

Proof

The control input signal (26) in a saturation condition (29) is defined as follows;

Substituting Eq. (25) into Eq. (33) yields;

By expanding Eq. (34) one can easily conclude;

Equation (35) has structure of conventional PID controller with coefficients of

The proof is completed.□

4 Results and discussion

In order to evaluate the performance of proposed methods, the nonlinear dynamics of the bubble in the vicinity of an elastic boundary (5) are tested under control input signals \(\left( {u_{Tra} \left( t \right)} \right)\) and \(\left( {u_{ISMC} \left( t \right)} \right)\). The simulations are performed by using Matlab-Simulink software with the step size \(.001\).

In the first simulation, the nonlinear dynamic of bubble (5) is evaluated under the traditional sliding mode controller (13). The parameters of the controller are selected as follows; \(\lambda = 50,K_{1} = 1.\) Fig. 4a shows the Bubble’s radial behavior under traditional sliding mode control (13). It is understood that the bubble with an initial radius of \(R_{0} = 2\;\upmu{\text{m}}\) successfully converged to the desired radius of \(R_{d} = 2.4\;\upmu{\text{m}}\). It means that the proposed method prevents bubble collapse or undesired oscillation. As shown in Fig. 4b, the control input signal (13) suffers from the chattering phenomenon. It should be noted that the chattering problem in the control input signal caused by the signum function in Eq. (13).

In the second simulation, the nonlinear dynamic of the bubble (5) under the boundary layer sliding mode controller is examined. The parameters of the controller are selected as follows; \(\lambda = 50,K_{1} = 1,\phi = .3 \, .\) bubble radius and control effort under the boundary layer sliding mode controller are depicted in Fig. 5a and b, respectively. By a simple comparison with traditional sliding mode control, it is easy to understand that the chattering problem is almost eliminated from the control effort signal but the tracking error and reaching time are increased.

In the third simulation, the nonlinear dynamic of the bubble (5) under the integral sliding mode controller (26) is evaluated. The parameters of the controller are selected as follows;\(\lambda_{1} = 50,\lambda_{2} = 1,K_{2} = 1,\phi = .01.\) Fig. 6a and b, present bubble radius, and control effort under integral sliding mode controller. It is clear that all control objectives including the elimination of chattering problem and convergence of tracking error to zero are satisfied under robust integral sliding mode control.

In order to carry out a comparative study between the performance of the proposed controller, root mean square error (RMSE) is introduced as follows;

where \(\left( {\Delta T = 6\;\upmu\text{s} } \right)\) is simulation time. According to Table 2, the best result in terms of time response and the quality of the control input signal is generated by using the integral sliding manifold controller. Fig 7 evaluates all three types of controllers in terms of minimizing tracking error. It is clear that the best result is achieved by using an integral sliding manifold.

In order to verify that the proposed method (26) is insensitive to parametric or structured uncertainties, the initial radius \(\left( {R_{0} } \right)\) and liquid viscosity \(\left( {\mu_{L} } \right)\) have been deviated by \(\pm \;30\%\). According to Fig. 8a and b integral sliding mode controller presents robust performance against initial radius uncertainty while other performance indexes such as reaching time, steady-state error and attenuation of chattering phenomenon are fulfilled.

Figure 9a and b present tracking performance of integral sliding mode control under uncertainty of liquid viscosity. Despite little variation from desired objectives such as steady-state error and reaching time, the controller still has acceptable performance.

5 Conclusion

In this paper, we have tackled the challenging problem of designing a robust integral sliding mode controller for an encapsulated microbubble in the vicinity of an elastic wall. The main contribution of this paper is to prevent nonlinear radial oscillation of encapsulated microbubble using nonlinear control methods. We start by representing the Rayleigh–Plesset-like equation into state-space form. Then three types of sliding mode controller including traditional, boundary layer and robust integral SMC are introduced. The simulation results confirmed the efficiency of integral SMC over traditional and boundary layer SMC in terms of minimizing chattering problem and improving time response performances. The work in this paper can be extended in many ways. For example, the design of a fuzzy controller for the nonlinear dynamic of encapsulated microbubble can also be tested. It is also possible to consider more complex bubble dynamics, such as two coupled bubbles or dynamic of encapsulated microbubble between two elastic walls.

References

Plesset MS, Prosperetti A (1977) Bubble dynamics and cavitation. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 9(1):145–185

Franc J-P (2007) The Rayleigh–Plesset equation: a simple and powerful tool to understand various aspects of cavitation. Fluid dynamics of cavitation and cavitating turbopumps. Springer, Berlin, pp 1–41

Turangan C et al (2006) Experimental and numerical study of transient bubble-elastic membrane interaction. J Appl Phys 100(5):054910

Sankin G, Zhong P (2006) Interaction between shock wave and single inertial bubbles near an elastic boundary. Phys Rev E 74(4):046304

Doinikov AA, Zhao S, Dayton PA (2009) Modeling of the acoustic response from contrast agent microbubbles near a rigid wall. Ultrasonics 49(2):195–201

Doinikov AA, Aired L, Bouakaz A (2011) Acoustic response from a bubble pulsating near a fluid layer of finite density and thickness. J Acoust Soc Am 129(2):616–621

Doinikov AA, Aired L, Bouakaz A (2011) Acoustic scattering from a contrast agent microbubble near an elastic wall of finite thickness. Phys Med Biol 56(21):6951

Caskey CF et al (2007) Direct observations of ultrasound microbubble contrast agent interaction with the microvessel wall. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 122(2):1191–1200

Doinikov A (2001) Translational motion of two interacting bubbles in a strong acoustic field. Phys Rev 64:026301

Zhao S, Ferrara KW, Dayton PA (2005) Asymmetric oscillation of adherent targeted ultrasound contrast agents. Appl Phys Lett 87(13):134103

Thomas D et al (2009) Single microbubble response using pulse sequences: initial results. Ultrasound Med Biol 35(1):112–119

Lankford M et al (2006) Effect of microbubble ligation to cells on ultrasound signal enhancement: implications for targeted imaging. Invest Radiol 41(10):721–728

Garbin V et al (2007) Changes in microbubble dynamics near a boundary revealed by combined optical micromanipulation and high-speed imaging. Appl Phys Lett 90(11):114103

Lentacker I, De Smedt SC, Sanders NN (2009) Drug loaded microbubble design for ultrasound triggered delivery. Soft Matter 5(11):2161–2170

Mayer CR, Bekeredjian R (2008) Ultrasonic gene and drug delivery to the cardiovascular system. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 60(10):1177–1192

Baseri B et al (2010) Multi-modality safety assessment of blood-brain barrier opening using focused ultrasound and definity microbubbles: a short-term study. Ultrasound Med Biol 36(9):1445–1459

Lindner JR (2004) Microbubbles in medical imaging: current applications and future directions. Nat Rev Drug Discovery 3(6):527

Mulvagh SL et al (2000) Contrast echocardiography: current and future applications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 13(4):331–342

Schrope BA, Newhouse VL (1993) Second harmonic ultrasonic blood perfusion measurement. Ultrasound Med Biol 19(7):567–579

Meyer K et al (2003) Harmonic imaging in acute stroke: detection of a cerebral perfusion deficit with ultrasound and perfusion MRI. J Neuroimaging 13(2):166–168

Rammohan S, Saseendran S, Kumaraswamy S (2009) Effect of multi jets on cavitation performance of globe valves. Journal of fluid science and technology 4(1):128–137

Amirante R, Distaso E, Tamburrano P (2014) Experimental and numerical analysis of cavitation in hydraulic proportional directional valves. Energy Convers Manag 87:208–219

Yaghoubi H, Madani SAH, Alizadeh M (2018) Numerical study on cavitation in a globe control valve with different numbers of anti-cavitation trims. Journal of Central South University 25(11):2677–2687

Gao F et al (2019) Distributed sliding mode control for formation of multiple nonlinear AVs coupled by uncertain topology. SN Applied Sciences 1(4):374

Levant A (2010) Chattering analysis. IEEE Trans Autom Control 55(6):1380–1389

Li Jn et al (2013) Chattering free sliding mode control for uncertain discrete time-delay singular systems. Asian J Control 15(1):260–269

Slotine J-JE (1984) Sliding controller design for non-linear systems. Int J Control 40(2):421–434

Rubagotti M et al (2011) Integral sliding mode control for nonlinear systems with matched and unmatched perturbations. IEEE Trans Autom Control 56(11):2699–2704

Munson BR et al (2013) Fluid mechanics. Wiley, Singapore

Brennen CE (2014) Cavitation and bubble dynamics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Doinikov AA, Aired L, Bouakaz A (2012) Dynamics of a contrast agent microbubble attached to an elastic wall. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 31(3):654–662

Katiyar A, Sarkar K, Jain P (2009) Effects of encapsulation elasticity on the stability of an encapsulated microbubble. J Colloid Interface Sci 336(2):519–525

Mettin R, et al. (2000) Dynamics of delay-coupled spherical bubbles. InL AIP conference proceedings. AIP

Kang C et al (2018) Effects of initial bubble size on geometric and motion characteristics of bubble released in water. J Cent South Univ 25(12):3021–3032

Castaños F, Fridman L (2006) Analysis and design of integral sliding manifolds for systems with unmatched perturbations. IEEE Trans Autom Control 51(5):853–858

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Mahmoud Najafi for his valuable comments on the progress of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights

Research involving no human participants and/or animals. The manuscript is processed through proper channel.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Badfar, E., Ardestani, M.A. Utilizing sliding mode control for the cavitation phenomenon and using the obtaining result in modern medicine. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1419 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1435-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1435-y