Abstract

Purpose

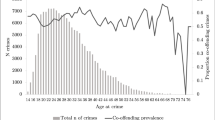

This study uses a sample of adult offenders to examine the relationships among age, co-offending, and within-person changes in criminal experience.

Methods

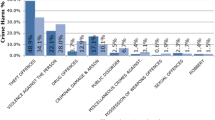

Burglary co-offending network data in one Pennsylvania county are analyzed to assess (1) the relationship between age and co-offending in a two-level framework, (2) the relationship between age and co-offender selection in a network regression model (MRQAP), and (3) within-person changes in experience and co-offending.

Results

Age predicts co-offending: younger offenders co-offend most often, while older offenders co-offend least often. Moreover, as offenders gain experience, the number of co-offenders per offense significantly decreases. Within-person analyses indicate that the best model of the transition from co-offending to solo offending includes age, experience, and the interaction of age and experience. Importantly, the effects of experience in reducing co-offending are significantly greater for older than younger offenders.

Conclusions

The results of the current study indicate that both age and experience must be included in future research on the transition from co-offending to solo-offending. The current study is limited to sentenced burglary offenders in one county. Future research should examine the effect of experience across offense types and across locations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

More than 64 % of the county is considered urban. Additionally, 51.1 % of the population is male and 91.4 % of the population is white.

The decision to include criminal trespassing offenses was made upon the recommendation of local criminal justice officials because of the number of burglary offenses in the county that are pled down to the lesser offense of criminal trespass (N = 90).

The sampling strategy used to collect additional co-offenders was extended to only one tie beyond convicted offenders. It is possible therefore that additional co-offenders further removed from convicted offenders (k = 2 or greater) are absent from the analyses. Many of these co-offenders did not have convictions for burglary, prohibiting us from extending the network further given the absence of police reports specific to these offenders.

Mixed offenders (those who both co-offend and solo-offend) must, by definition, commit at least two offenses, but over 67 % of the offenders in the sample committed only one offense. Because those who commit multiple offenses are parsed out and analyzed separately later in the paper for changes in co-offending, and because further segmenting those who commit multiple offenses into exclusive co-offenders, solo offenders, and mixed offenders would result in small cell sizes and reduced statistical power, the co-offender measure includes offenders who both exclusively co-offend, and who offend both with others and by themselves (i.e., mixed).

As Ouellet et al. [36] point, out, many offenders are arrested only once in their burglary careers. Once arrested, they are subsequently charged and sentenced with several past offenses for some combination of two reasons: they confess to several additional burglary offenses after they are arrested, or they commit several burglary offenses before the police are able to make the arrest (see also [24]). Thus, even though the burglaries for these offenders occurred at different times, because the offender was arrested only once, age at arrest does not vary over time.

Because the network was relatively disconnected to begin with, the Girvan-Newman algorithm created subgroups that were substantively similar to the initial network components. Results were substantively similar across group structures.

MRQAP regressions are based on permutation tests. As a result, significance tests are not constructed according to the same logic of classical regression techniques. The classical significance test calculates the probability of obtaining the coefficient provided that the variables are actually independent. When the probability is less than 5 %, the result is significant at the 0.05 level. A permutation test, however, calculates several random matrices and estimates the proportion of random assignments that result in a correlation as large as that actually observed. If the original correlation is larger than 95 % of permutations, the results are significant at the 0.05 level. Because significance tests are based on permutations, rather than the actual sample, significance is not affected by the sample size in the same way as with traditional regression analyses.

We conducted sensitivity analyses using an alternative specification of total experience, offense span, or the length of the offender’s criminal career measured in days. Results were substantively similar (i.e., all coefficients retained their significance).

Because this offender may have been an outlier, sensitivity analyses were conducted wherein this offender was excluded from the analysis. The results were substantively unchanged, and all coefficients retained their significance.

The coefficient for experience-squared is also statistically significant. The estimate is substantively small, but we chose to include the term in the model in order to accurately graph the non-linear functional form of the relationship.

Theft value is a continuous measure indicating the value of stolen goods, in US dollars, of the property stolen during a burglary incident. Most, but not all, burglary offenses included theft; a control measure for whether or not a theft was committed during the offense is also included. Days before arrest is a continuous measure indicating the number of days between the offense date and the arrest date of the offender(s). It is important to note that, because the data are based on conviction records, any measure of apprehension avoidance is relative. Essentially, days before arrest is a measure of how long the offenders avoided arrest before at least one of the offenders was apprehended. Offense completion is coded as a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not an offense was completed (1 = yes). An offense is coded as not completed if the police arrested the offender(s) in the course of the offense or the offender(s) were unable to complete the offense for another reason (e.g., interrupted by a homeowner).

Co-offending is positively and significantly associated with offense completion (p < .05) in earlier iterations of the model. The inclusion of group density, however, mediates the co-offending effect.

Unfortunately, however, we are unable to disentangle the temporal order of this relationship. While this effect may indicate that those with more access to potential co-offenders offend with others more often, it is perhaps equally plausible that offenders who offend with many others have larger co-offending groups because of these offending patterns.

References

Alarid, L. F., Burton, V., & Hochstetler, A. (2009). Group and solo robberies: do accomplices shape criminal form? Journal of Criminal Justice, 37, 1–9.

Andresen, M. A., & Felson, M. (2010). The impact of co-offending. British Journal of Criminology, 50, 66–81.

Andresen, M. A., & Felson, M. (2012). Co-offending and the diversification of crime types. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 56, 811–829.

Bennett, T., & Wright, R. (1984). Burglars on burglary: prevention and the offender. Brookfield: Avebury Publishing.

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., & Johnson, J. C. (2013). Analyzing social networks. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Bouchard, M., & Nguyen, H. (2010). Is it who you know, or How many that counts?: Criminal networks and cost avoidance in a sample of young offenders. Justice Quarterly, 27, 130–158.

Carrington, P. J. (2002). Group crime in Canada. Canadian Journal of Criminology, 44, 277–315.

Carrington, P. J. (2009). Co-offending and the development of the delinquent career. Criminology, 47, 1295–1329.

Carrington, P. J. (2015). The structure of Age homophily in Co-offending groups. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 31(3), 337–353.

Carrington, P. J., & van Mastrigt, S. B. (2013). Co-offending in Canada, England and the United States: a cross-national comparison. Global Crime, 14, 123–140.

Conway, K. P., & McCord, J. (2002). A longitudinal examination of the relation between Co-offending with violent accomplices and violent crime. Aggressive Behavior, 28, 97–108.

Desroches, F.J. (2005). The Crime that Pays: Drug Trafficking and Organized Crime in Canada. Canadian Scholars Press.

Erickson, M. (1971). The group context of delinquent behavior. Social Problems, 19, 114–129.

Felson, M. (2003). The process of co-offending. In M. J. Smith & D. B. Cornish (Eds.), Theory for practice in situational crime prevention: crime prevention studies (Vol. 16). Monsey: Criminal Justice Press.

Feyerherm, W. (1980). The group hazard hypothesis: a re-examination. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 17, 58–68.

Goldweber, A., Dmitrieva, J., Cauffman, E., Piquero, A. R., & Steinberg, L. (2013). The development of criminal style in adolescence and young adulthood: separating the lemmings from the loners. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 332–346.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hirschi, T., & Gottfredson, M. (1983). Age and the explanation of crime. American Journal of Sociology, 89, 552–584.

Hood, R., & Sparks, R. (1970). Key issues in criminology. London: World University Library.

Jacobs, B. (1996). Crack dealers’ apprehension avoidance techniques: a case of restrictive deterrence. Justice Quarterly, 13, 359–381.

Kornhauser, R. (1978). Social sources of delinquency: an appraisal of analytic models. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kreager, D. A., Rulison, K., & Moody, J. (2011). Delinquency and the structure of adolescent peer groups. Criminology, 49(1), 95–127.

Lantz, B., & Hutchison, R. (2015). Co-offender ties and the criminal career: group characteristics, persistence, desistance, and the individual offender. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 52(5), 658–690.

Lantz, B. & Ruback, R.B. (2015). A Networked Boost: Co-Offending and Repeat Victimization Using a Network Approach. Crime & Delinquency (Online First).

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: delinquent boys to age 70. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Leenders, R. T. A. J. (1997). Longitudinal behavior of network structure and actor attributes: Modeling interdependence of contagion and selection. In Evolution of Social Networks. New York: Gordon and Beach.

McCarthy, B., & Hagan, J. (1995). Getting into street crime: The structure and process of criminal embeddedness. Social Science Research, 24, 63–95.

McCarthy, B., & Hagan, J. (2001). When crime pays: capital, competence, and criminal success. Social Forces, 79, 1035–1059.

McGloin, J. M., & Nguyen, H. (2012). It was my idea: considering the instigation of co-offending. Criminology, 50, 463–494.

McGloin, J. M., & Piquero, A. R. (2010). On the relationship between co-offendign network redundancy and offending versatility. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 47(1), 63–90.

McGloin, J. M., Sullivan, C. J., Piquero, A. R., & Bacon, S. (2008). Investigating the stability of co-offending and co-offenders among a sample of youthful offenders. Criminology, 46, 155–187.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Osgood, D. W. (2012). A future trajectory for life course criminology. In R. Loeber & B. C. Welsh (Eds.), Future of criminology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Osgood, D. W., Wilson, J. K., Bachman, J. G., O’Malley, P. M., & Johnston, L. D. (1996). Routine activities and individual delinquent behavior. American Sociological Review, 61, 635–655.

Ouellet, F., Boivin, R., Leclerc, C., & Morselli, C. (2013). Friends with(out) benefits: co-offending and re-arrest. Global Crime, 14, 141–154.

Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P., & Blumstein, A. (2007). Key issues in criminal career research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Reiss, A. J. (1986). Co-offender influences on criminal careers. In Criminal careers and career criminals (pp. 121–160).

Reiss, A. J., Jr. (1988). Co-offending and criminal careers. Crime and Justice, 10, 117.

Reiss, A. J., & Farrington, D. P. (1991). Advancing knowledge about co-offending: results from a prospective longitudinal study of London males. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 82, 360–395.

Sarnecki, J. (2001). Delinquent networks: youth co-offending in Stockholm. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schaefer, D. R., Rodriguez, N., & Decker, S. H. (2014). The role of neighborhood context in youth co-offending. Criminology, 52(1), 117–139.

Shaw, C. & McKay, H.D. (1931). Social Factors in Juvenile Delinquency. Government Press.

Shover, N. (1991). Burglary. Crime and Justice, 14, 73–113.

Stolzenberg, L., & D’Alessio, S. J. (2008). Co-offending and the age-crime curve. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 45, 65.

Sweeten, G., Piquero, A. R., & Steinberg, L. (2013). Age and the explanation of crime, revisited. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 921–938.

Tillyer, M. S., & Tillyer, R. (2014). Maybe i should do this alone: a comparison of solo and co-offending robbery outcomes. Justice Quarterly, 32, 1–25.

Tremblay, P. (1993). Searching for suitable co-offenders. Routine Activity and Rational Choice, 5, 17–36.

van Mastright, S. B., & Farrington, D. P. (2009). Co-offending, age, gender and crime type: implications for criminal justice policy. British Journal of Criminology, 49(4), 552–573.

van Mastrigt, S.B. 2008. “Co-offending: Relationships with Age, Gender, and Crime Type.” PhD Dissertation. Institute of Criminology, University of Cambridge, UK.

Warr, M. (1998). Life-course transitions and desistance from crime. Criminology, 36(2), 183–216.

Warr, M. (2002). Companions in crime: the social aspects of criminal conduct. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weerman, F. M. (2003). Co-offending as social exchange: explaining characteristics of co-offending. British Journal of Criminology, 43, 398–416.

Weerman, F. M. (2014). Theories of co-offending. In G. Bruinsma & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice. New York: Springer.

Wright, R.T. & Decker, S.H. 1994. Burglars on the job: Streetlife and residential break-ins. UPNE.

Zimring, F.E. & Laqueur, H. (2014). Kids, Groups, and Crime: In Defense of Conventional Wisdom. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 1–11.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lantz, B., Ruback, R.B. The Relationship Between Co-Offending, Age, and Experience Using a Sample of Adult Burglary Offenders. J Dev Life Course Criminology 3, 76–97 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-016-0047-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-016-0047-0