Abstract

Background

We evaluated the differences within various ethnic groups diagnosed with head and neck cancer in the USA with a specific focus on the clinical outcomes of patients of Hispanic ethnicity.

Material/Methods

We used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database to examine the clinical outcomes of patients with head and neck cancer by ethnicity, region of origin, place of birth, treatment modality, primary location, age, gender, and SEER tumor stage.

Results

For all patients, African American race conferred the worst prognosis for head and neck cancer (1.41; CI 1.361–1.454), while non-US born Hispanics had the best prognosis (0.74; 0.684–0.804). US born Hispanics (0.86; CI 0.823–0.892) had a significantly better prognosis than Whites (ref.).

Conclusion

The Hispanic population appears to have a better prognosis compared to their Caucasian peers while both do better than Blacks across all stages and in local and regional disease subsets. Furthermore, non-US born Hispanics had a better prognosis than US born Hispanics. The cause of this disparity is unclear and warrants further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Head and neck cancers,—cancers arising from the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx,—account for up to 5 % of all cancers in the USA [1]. In 2012, cancers from these sites are expected to result in nearly 53,000 new cases and 11,500 deaths in the USA alone [2]. Treatment for head and neck cancer costs approximately $3.2 billion annually [3]. Due to their clinically silent progression and subsequent advanced presentation, head and neck cancers often require an interdisciplinary approach to oncologic management. In addition to the challenge of maximizing survival, treatment options—surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy—are dependent on cancer site, stage of disease, and considerations of functionality and cosmesis [4, 5].

Of critical significance in head and neck cancer management is the dramatic difference in cure rates between early stage and late stage disease: head and neck cancers have an estimated overall cure rate of 50 %, while stage I disease cure rates approach 90 % [6]. In addition, advanced head and neck cancers are associated with significant swallowing and speech dysfunction that impair quality of life. Given the substantial morbidity and mortality associated with head and neck cancers, and particularly, the poor prognosis of advanced stage presentations, studies have attempted to address the issues of racial and ethnic disparities in head and neck cancer in an attempt to improve clinical outcomes [6–15]. Much of this research, while still limited, has focused on the significant differences in incidence, stage of presentation, and survival between African Americans and Whites [6–14]. Previous studies have suggested that African American men and women have poorer 5-year survival rates for head and neck cancers largely due to socioeconomic status, later stage of presentation, and less access to appropriate cancer-directed treatment [6–14]. More concerning, Goodwin et al. reveal that between 1975 and 2002, trends in survival after diagnosis indicate a widening disparity between Blacks and Whites. In larynx cancer, for example, Black males witnessed a decrease in 5-year survival disparity from 58.3 % (1975–1977) to 54.5 % (1996–2002), while White males experienced an increase in survival from 67.9 % (1975–1977) to 69.1 % (1996–2002) [6].

While African American ethnicity, marital status, and socioeconomic status have all been associated with outcomes in head and neck cancer, how the Hispanic ethnicity relates to clinical outcome is a question that remains without an established answer [16–18]. An improved understanding of disparities in survival among populations with head and neck cancer may enable targeted treatment, prevention, and public health interventions for specific subgroups that could yield improved clinical outcomes. In this study, we attempt to evaluate the differences among the US various ethnic groups diagnosed with head and neck cancer. We specifically focused on the clinical outcomes of patients with Hispanic background.

Materials and Methods

Data for this retrospective study was obtained from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program using the 17-Registry 1973–2007 data set, November 2009 Submission, released April 2010. The SEER Program is the only comprehensive source of population-based information in the USA that includes stage of cancer at the time of diagnosis, first course of treatment, and patient survival data.

From the SEER database, we assembled a cohort of patients aged 21 years and older with pathologically confirmed, squamous cell cancers of the head and neck (HNC) diagnosed from 1991 to later. We excluded patient with cancers of the nasopharynx due to its distinct presentation, etiology, clinical behavior, and prognosis when compared with other head and neck subsites. Based on the Collaborative staging schema, HNC was classified into one of the following subsites: (1) oral cavity (5-10, 12, 13), oral pharynx (4, 11, 17, 21), hypopharynx (20), and larynx (18, 42-45). Staging was based on the SEER historical stage A (in situ, localized, regional, metastatic). Hispanic ethnicity was based on the NAACCR Hispanic identification algorithm. This is a computerized algorithm that uses a combination of variables to classify as Hispanic for analytic purposes. The Hispanics were then classified as US born or foreign born (birth in Central America or South America). By definition, patients living in Brazil were not considered Hispanic. Patients without a country of birth were excluded from analysis. Race and ethnicity were combined into a single variable for this study to avoid potential double counting. Potential covariates included patient age at diagnosis, sex, tumor stage, tumor subsite, and treatment (surgery, radiotherapy, or both). Data on performance status, use of adjuvant chemotherapy, and radiotherapy treatment details (dose, fractionation, beam energy, field size, etc.) were not available within the SEER database and are not included in this analysis. Proportional hazards models were used to examine the adjusted association of race/ethnicity and potential covariates with overall survival. Hazard ratios greater than 1.00 were associated with worse survival. Patients contributed person-time from the date of their diagnosis until they died. All data were analyzed using SAS Version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) statistical software package.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Demographic, disease, and treatment characteristics of study patients are summarized in Table 1. Male patients composed 72.4 % of the cohort. Of the patients, 12.8 % were under the age of 50 years old, 55.9 % between 50 and 70 years old, and 31.3 % over 70 years old. Whites made up 75.7 % of the cohort, Blacks 11.9 %, Mexicans 1.7 %, Cuban/Dominican 0.3 %, Central American 0.3 %, South American 0.3 %, and US-born Hispanics 9.8 %. Stage was distributed as follows: 4.2 % of patients had in situ disease, 33.4 % local, 52.5 % regional involvement, and 9.9 % distant disease. Treatment consisted of surgery in 34 %, radiation 29.8 %, and combined modality in 36.2 %. The primary site for disease was oral cavity in 33.1 %, oropharynx in 32 %, hypopharynx in 7.6 %, and larynx in 27.3 % of the cases.

Stage of Disease

For all patients with head and neck cancer, the distribution of stage by ethnicity is summarized in Table 2. For presentation with in situ disease, Blacks had the lowest proportion with only 2.6 %, compared to 3.0 % for US-born Hispanics, 3.8 % for non-US-born Hispanics, and 4.6 % for Whites. Black populations had the highest rates of regional (58.0 %) and distant (14.6 %) disease, followed by non-US-born Hispanics (54.7 and 11.8 %), US-born Hispanics (52.4 and 9.4 %), and Whites (51.5 and 9.2 %, respectively). Within the non-US-born Hispanic population, South Americans tended to have the least advanced disease with only 45.1 % regional and 5.6 % distant; consequently, this group had the highest rates of in situ (4.9 %) and localized (44.4 %) disease.

Primary Site

The distribution of primary site by ethnicity is summarized in Table 3. For oropharynx and hypopharynx malignancies, non-US-born Hispanics have the lowest rates at 26.6 and 6.5 %, respectively, while Blacks had the highest rates at 34.3 and 10.1 %, respectively. Blacks had the lowest proportion of oral cavity cancers (23.4 %), followed by Whites (33.8 %), non-US-born Hispanics (36.9 %), and US-born Hispanics (39.0 %). For larynx primary site malignancies, Blacks had the highest proportion (32.1 %), followed by non-US-born Hispanics (30.0 %), Whites (26.8 %), and US-born Hispanics (24.85 %). For all ethnicities, South Americans had the highest proportion of oral cavity primaries (42.4 %) and the lowest number of hypopharynx (3.5 %) and larynx malignancies (23.6 %).

Within the non-US-born Hispanic population, the proportion of primary site varied considerably based upon ethnicity: oral cavity [27.8 % (Cuban/DR) to 42.4 % (South American)]; oropharynx [24.7 % (Mexican) to 33.3 % (Cuban/DR)]; hypopharynx [3.5 % (South American) to 7.5 % (Mexican)]; and larynx [23.6 % (South American) to 34.9 % (Cuban/DR)].

Survival

The univariate subset analysis of 5-year survival by age, sex, ethnicity, primary site, and staging are summarized in Table 4. Survival rates decreased with increasing age: 49.1 % for patients under 50 years old, compared to 41.6 % for patients between 50 and 70 years old, and only 29.9 % for patients over 70 years old. Our results reveal similar survival rates for males (38.8 %) and females (39.9 %). In addition, survival rates decreased with more advance disease: in situ (62.0 %), localized (50.7 %), regional (33.0 %), and distant (17.2 %). We observed considerable variability in survival based on the primary site of head and neck cancers. Primary malignancies arising from the larynx had the highest survival rates at 45.0 %, followed by the oropharynx at 38.2 %, the oral cavity at 38.0 %, and finally the hypopharynx at 21.1 %.

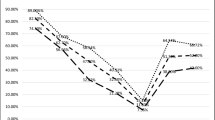

Our study indicates that Hispanic ethnicity, both non-US born and US born, conferred a better prognosis for head and neck cancer. Non-US-born Hispanics had the highest 5-year survival rates (49.3 %) out of all patients with head and neck cancer, followed by US-born Hispanics at 44.9 %. Whites had survival rates of 39.6 %, while Blacks had the worst prognosis with survival rates of only 27.2 % (Fig. 1). Every subgroups within the non-US-born Hispanic population (South American, Central American, Cuban/DR, and Mexican) had higher survival rates than US-born Hispanics, Whites, and Blacks. Within the non-US-born Hispanic population, South Americans had the highest survival rates (55.3 %), followed by both the Central American and Cuban/DR subgroups (49.5 %), and Mexicans (37.93 %).

Multivariate Survival

Multivariate analysis of survival for all patients with head and neck cancer is summarized in Table 5. Our analysis showed age, gender, ethnicity, tumor stage, primary site of disease, and treatment to be independent predictors of survival. Increasing age (1.03; CI 1.025–1.027) confers a statistically significant worse prognosis. Female patients (0.95; CI 0.923–0.972) do significantly better than their male counterparts (ref.). More advanced disease has significantly worse prognosis: in situ (0.52; CI 0.483–0.548), localized (0.60; CI 0.582–0.615), regional (ref.), and distant (1.72; CI 1.656–1.781). For primary site, the tumors of the larynx had the best prognosis (0.96; 0.925–0.981), followed by oropharynx (ref.), oral cavity (1.29; 1.253–1.336), and hypopharynx (1.41; 1.347–1.467). African American race conferred the worst prognosis for head and neck cancer (1.41; CI 1.361–1.454), while non-US-born Hispanics had the best prognosis (0.74; 0.684–0.804). US-born Hispanics (0.86; CI 0.823–0.892) had a significantly better prognosis than Whites (ref.). For treatment, surgery alone (0.95; CI 0.922–0.981) had a significantly better prognosis than radiotherapy (1.36; 1.325–1.398) and combined treatment with surgery and radiation (ref.).

Local and Regional Disease

Multivariate analysis of survival for patients with only local and regional disease is summarized in Tables 6 and 7. For these subsets, our results suggests similarly improved prognosis with decreased age and female gender. In concordance with our results for all patients, Hispanics have a better prognosis than Whites and Blacks for local and regional disease. In addition, non-US-born Hispanics do better than US-born Hispanics in both of these subsets.

Of note, the prognosis based on primary site of malignancy varies for local and regional disease as compared to the results for all patients. For local disease, the larynx (0.586; CI 0.551–0.624) and hypopharynx (1.142; CI 1.009–1.292) continue to confer the best and worst prognosis, respectively. For regional disease, the larynx (1.101; CI 1.057–1.147); oral cavity (1.472; CI 1.412–1.534), and hypopharynx (1.492; CI 1.418–1.571) all had worse prognosis than tumors of the oropharynx (ref.).

For local disease, surgery showed better survival compared to radiotherapy and combined therapy. However, when only patients with regional disease were assessed, surgery and combined therapy with surgery and radiation were not significantly different.

Discussion

Our results suggest that Hispanic ethnicity confers better prognosis in head and neck cancer. Furthermore, non-US-born Hispanics have a better prognosis than US-born Hispanics. African Americans do worse than both their White and Hispanic counterparts. These findings represent a comprehensive analysis associating Hispanic ethnicity with outcomes in head and neck cancer and challenge many of the previous theories of health care disparities among minority populations.

Other more limited studies have examined Hispanic outcomes in head and neck cancer [7, 16–18]. Molina et al. analyze the Florida Cancer Data System and show Hispanics (0.89; CI 0.788–1.006) have similar prognosis to non-Hispanics on multivariate analysis; however, their results fail to reach statistical significance (p = 0.062) [7]. Using a stepwise, multivariate analysis, Molina et al. found untreated Hispanics to do better than untreated non-Hispanics (0.890; CI 0.776–0.999; p = 0.048), suggesting the possibility of favorable genetic/environment factors among Hispanics [7]. In a study with a primary emphasis on comparing outcomes in oral and pharyngeal cancer between Hispanics in Puerto Rico, US Hispanics, non-Hispanic Whites, and non-Hispanic Blacks, Suarez et al. find US Hispanic men and women to have a lower incidence and mortality than non-Hispanic Whites using age-standardized rates (per 100,000) [17]. They demonstrated US Hispanic men to have an incidence of 9.5 and mortality rate of 3.5 compared to their White counterparts rates of 16.3 and 4.4 (per 100,000), respectively. Hispanic females also had lower incidence rates (4.3 vs. 7.1 per 100,000) and mortality rates (1.2 vs. 2.0 per 100,000) than their White females, respectively. They suggest that the substantially lower incidence rates with similar mortality rates highlight inequity in health care access and practices [17]. Of note, this study only evaluated oral and pharyngeal cancers. Chen et al. compare Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites through a match-pair analysis intended to standardize for the provision of care. Their study found no statistically significant difference in survival between Hispanics and non-Hispanics [16]. Although with a limited sample size, their results indicated a statistically significant site-specific disparity in overall survival between Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites (5.00; 1.07–6.93) for oropharyngeal cancer, suggesting a biological factor influencing outcomes [17].

Prior studies suggest that much of the racial disparity in head and neck cancer outcomes can be linked to confounding variables such as smoking and treatment. These two variables were not available for our analysis. The reason for the survival disparity among racial and ethnic groups in this study is unknown. Examining the differences in distribution of stage as a source for survival disparities reveals a mixed picture. For the survival advantage conferred by the Hispanic ethnicity, the results do not seem linked to disease staging: Whites had similar or more localized disease compared to both non-US-born Hispanics and US-born Hispanics. However, South Americans, the ethnic subgroup with the best prognosis among all populations, had the highest proportion of in situ and localized disease. All three ethnic groups, non-US-born Hispanics, US-born Hispanics, and Whites, had more favorable staging profiles than African Americans, who have the poorest prognosis.

HPV-associated head and neck cancers are primarily confined to the oropharynx, are increasing in incidence, and are associated with improved prognosis. However, HPV does not seem to explain the survival disparity either as oropharyngeal tumors are the least common in non-US-born Hispanics, the group with the best prognosis. Lack of HPV typing, a limit of this database, may be masking occult differences [18, 19].

In addition to tobacco, alcohol use [20, 21], and infection with human papilloma virus (HPV) [22], other risk factors include exposure to industrial agents, poor nutrition [23], and family history also contribute to risk [24]. Furthermore, environmental factors such as diet and lifestyle have increasingly been linked to cancer. In a prospective study evaluating obesity and cancer mortality in the USA, Calle et al. find overweight and obesity to account for 14 % of all cancer deaths in men and 20 % in women. For individuals with a body mass index above 40, they show a relative risk of 1.52 (1.13–2.05) for men and 1.62 (1.40–1.87) for women [25].

Many of these risk factors have a much higher prevalence in the USA than the countries of Hispanic origin used in this study. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 35.1 % of the US population is obese, compared to 11.1 % in Brazil, 11.8 % in Cuba, 16.8 % in the Dominican Republic, and 23.6 % in Mexico. [24] In 2001, the USA had the higher rates of alcohol consumption among adults than Brazil, Mexico, Cuba, or the Dominican Republic [26]. Within the USA, Molina et al. found significantly less tobacco (74 vs. 83 %; p < 0.001) and alcohol (15 vs. 18 %; p < 0.001) use among Hispanics when compared to non-Hispanics, respectively [7]. A recent CDC analysis found Hispanics (19.7 %) to have significantly lower tobacco use than non-Hispanic Whites (26.2 %) and non-Hispanic Blacks (24.4 %) [27]. These stark differences in lifestyle choices may, in part, explain the improved survival of Hispanics and, specifically, non-US-born Hispanics.

The trend for Hispanics to have better-than-expected health outcomes, given their lower socioeconomic status, has been described as the Hispanic paradox [28, 29]. Many have argued that these results are due to migrant health selectivity (healthy individuals immigrate to the USA, while the sick return to their place of origin) [30, 31]. Others have noted that new Hispanic immigrants are healthier than the US-born population, but their incidence of chronic conditions and poor health behaviors (high fat diet and sedentary lifestyle) increases with increased time of residence [32, 33]. Kaplan et al. find prevalence of obesity among Hispanic immigrants to increase from 9.4 % (0 to 4 years of residence in the USA) to 24.2 % (15 or more years of residence in the USA) [31]. The precise cause of the Hispanic paradox is likely multi-factorial. Nonetheless, lifestyle choices seem to play an integral role in the health status difference between non-US-born Hispanics and US-born Hispanics.

While this study represents the most comprehensive analysis of Hispanic ethnicity and outcomes in head and neck cancer, the SEER database, and as a result this study, has limitations that must be noted. As already briefly discussed, the SEER database has limited data on comorbidities, smoking and alcohol use, chemotherapy use, and details of radiation therapy delivery, limiting effective matching of these potentially confounding variables. In addition, these studies cannot account for geographic variations in standards of care or resources. As an example, the survival difference witnessed between surgery and radiotherapy may in part be explained by selection bias during treatment recommendation. In addition, even within each staging group, detailed TNM staging data is lacking. As a result, local and regional groups represent heterogeneous populations with potentially differing prognosis.

This analysis varies from that as published by Schrank et al. this study used a more extensive dataset with further follow-up [34].The Schrank study limited patients to those diagnosed after 1988 and truncated at 2005, which may explain the difference in results. The improved outcomes seen by Hispanics in other studies may be masked by disparities in HPV+ cancers which disproportionately affects Caucasians [35]. Caucasians had the highest percentage of oropharyngeal cancers in this study. It is difficult to assess the relevance of the Hispanic subgroups analyzed in this study, given the potential environmental, cultural and other confounding variables, and the limited data available when utilizing SEER.

Further translational studies are needed to examine the role of ethnicity and clinical outcomes in head and neck cancer. Such studies would enable adequate matching of confounding variables such as risk factors, patient support, and treatment standards, and provide for a more comprehensive understanding of the causes of disparities in head and neck cancer. Ultimately, these studies could provide for targeted treatment, prevention, and public health interventions for specific subgroups that could yield improved clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

Ethnicity has been associated with clinical outcome in head and neck cancer in the past. Using the SEER database, we show that Hispanic population appears to have a better prognosis compared to their Caucasian peers while both do better than Blacks. This was observed across all stages and also in patients with local and regional disease. Furthermore, non-US-born Hispanic had the best prognosis followed by the US born Hispanic group. The cause of this disparity is unclear and warrants further investigation.

References

National Cancer Institute. Head and neck cancer fact sheet. National Institutes of Health, 2005.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2012. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2012.

National Cancer Institute. Cancer trends progress report—2009/2010 update. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health; 2010.

Brizel DM, Albers ME, Fisher SR, et al. Hyperfractionated irradiation with or without concurrent chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1798–804.

Shah JP, Lydiatt W. Treatment of cancer of the head and neck. CA-A Cancer J Clin. 1995;45:352–68.

Goodwin WJ, Thomas GR, Parker DF, et al. Unequal burden of head and neck cancer in the United States. Head Neck. 2008;30(3):358–71.

Molina MA, Cheung MC, Perez EA, et al. African American and poor patients have dramatically worse prognosis for head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(10):2797–806.

Nichols CA, Battacharyya N. Racial differences in stage and survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:770–5.

Shavers VL, Harlan LC, Winn D, Davis WW. Racial/ethnic patterns of care for cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, sinuses, and salivary glands. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:25–38.

Arbes Jr SJ, Olshan AF, Caplan DJ, Schoenbach VJ, Slade GD, Symons MJ. Factors contributing to the poorer survival of black Americans diagnosed with oral cancer (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:513–23.

Murdock JM, Gluckman JL. African-American and white head and neck carcinoma patients in a university medical center setting. Are treatments provided and are outcomes similar or disparate? Cancer. 2001;91:279–83.

Tomar SL, Loree M, Logan H. Racial differences in oral and pharyngeal cancer treatment and survival in Florida. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:601–9.

Bach PB, Schrag D, Brawley OW, Galaznik A, Yakren S, Begg CB. Survival of blacks and whites after a cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2002;287:2106–13.

Gourin CG, Podolsky RH. Racial disparities in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1093–106.

Filon EJ, McClure LA, Huang D, et al. Higher incidence of head and neck cancers among Vietnames American men in California. Head Neck 2010; 1-9.

Chen LM, Li G, Reitzel LR, et al. Matched-pair analysis of race or ethnicity in outcomes of head and neck cancer patients receiving similar multidisciplinary care. Cancer Prev Res. 2009;2(9):782–91.

Suarez E, Calo WA, Hernandez EY, et al. Age-standardized incidence and mortality rates of oral and pharyngeal cancer in Puerto Rico and among non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, and Hispanics in the USA. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:129.

Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tan PF, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24–35.

Simard EP, Ward EM, Siegel R, Jemal A. Cancers with increasing incidence trends in the United States: 1999 through 2008. CA Cancer J Clin 2012.

Mayne ST, Morse DE, Winn DM. Cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx. In: Schottenfeld DA, Fraumeni Jr JF, editors. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 674–96.

Block G, Patterson B, Subar A. Fruit, vegetables, and cancer. Nutr Cancer. 1992;18:1–29.

De Petrini M, Ritta M, Schena M, et al. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: role of the human papillomavirus in tumour progression. New Microbiol. 2006;29:25–33.

Harris GJ, Clark GM, Von Hoff DD. Hispanic patients with head and neck cancer do not have a worse prognosis than Anglo-American patients. Cancer. 1992;69:1003–7.

Foulkes WD, Brunet JS, Kowalski LP, Narod SA, Franco EL. Family history of cancer is a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in Brazil: a case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1995;63:769–73.

Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–38.

World Health Organization. Global database on body mass index. 2010. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Any tobacco use in 13 states—behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2008. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(30):946–50.

Franzini L, Ribble J, Keddie AM. Understanding the Hispanic paradox. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:496–518.

Palloni A, Morenoff JD. Interpreting the paradoxical in the Hispanic paradox: demographic and epidemiologic approach. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;954:140–74.

Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1543–8.

Palloni A, Arias E. Paradox lost: Explaining the Hispanic adult mortality advantage. Demography. 2004;41:385–415.

Singh GK, Siahpush M. Ethnic-immigrant differentials in health behaviors, morbidity, and cause-specific mortality in the United States: an analysis of two national databases. Hum Biol. 2002;74:83–109.

Kaplan MS, Huguet N, Newsom JT, McFarland BH. The association between length of residence and obesity among Hispanic immigrants. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(4):323–6.

Schrank T, Han Y, Weiss H, Resto B. Case-matching analysis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in racial and ethnic minorities in the United States—possible role for human papillomavirus in survival disparities. Head Neck. 2011;33(1):45–54.

Settle K, Posner MR, Schumaker LM. Racial survival disparity in head and neck cancer results from low prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in black oropharyngeal cancer patients. Cancer Prev Res. 2009;2:776–78.

Ethical Standards

No animal or human studies were carried out by the authors for this article

Conflict of Interest

Abramowitz, Parasher, Lally, Weed, Franzman, Goodwin, and Hu declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parasher, A.K., Abramowitz, M., Weed, D. et al. Ethnicity and Clinical Outcomes in Head and Neck Cancer: an Analysis of the SEER Database. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 1, 267–274 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-014-0033-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-014-0033-3