Abstract

Introduction

In clinical trials, treatment with the interleukin-23 inhibitor guselkumab was associated with significantly improved disease severity and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) among patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. However, limited information is available regarding the real-world effectiveness of guselkumab among patients with psoriasis of mild, moderate, and severe Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) severities living in the USA and Canada.

Methods

Patients participating in the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry between 18 July 2017 and 10 July 2019 who met the following criteria were included: IGA ≥ 2 (mild or greater disease severity), initiated guselkumab at a registry (index) visit, and had a registry follow-up visit after persistent guselkumab treatment for 9 to 12 months. Data were collected for patient demographics, disease characteristics, treatment history, disease activity, and PROMs. At follow-up, outcome measure response rates and mean changes from the index visit were calculated.

Results

Among 130 patients, the mean age was 50.2 years, 39.2% were female, and 56.9% had a body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2. Mean psoriasis duration was 17.5 years and 79.2% of patients had previously received one or more biologic therapy. At the index visit, mean IGA, Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI), and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores were 3.0, 9.9, and 8.0, respectively. At follow-up, IGA 0/1 and IGA 0 were achieved by 64.6% and 36.2% of patients, respectively. PASI 75, 90, and 100 were achieved by 61.5%, 46.9%, and 36.9% of patients; 55.4% had maintained or achieved DLQI 0/1. Mean improvements were observed in all evaluated disease activity outcomes and PROMs, with all differing significantly from zero except for the percent of work hours missed due to psoriasis.

Conclusion

In this real-world study, patients with a baseline IGA score ≥ 2 experienced improvements in disease activity and PROMs after 9–12 months of persistent guselkumab treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Why carry out this study? |

Guselkumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody that binds to the p19 subunit of interleukin-23, has shown improvement of clinical disease outcomes and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and has an established safety profile in moderate-to-severe psoriasis. |

Although clinical trials have typically focused on specific criteria for moderate-to-severe psoriasis, patient populations receiving guselkumab in the real world may reflect all Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) severities of the disease; limited information is available regarding outcomes after guselkumab therapy in typical clinical practice in the USA and Canada. |

The objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of 9–12 months of persistent guselkumab therapy among US and Canadian patients with plaque psoriasis and a baseline IGA score ≥2 (mild or greater disease severity) who initiated treatment in the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry. |

What was learned from this study? |

At follow-up, guselkumab-treated patients showed reductions in the severity of their disease; furthermore, all mean changes in disease activity and PROMs showed improvement, with all differing significantly from zero except for the percentage of work hours missed because of psoriasis. |

To our knowledge, this is the first real-world study to evaluate outcomes among patients with mild, moderate, and severe IGA severities of psoriasis who received guselkumab therapy in the USA and Canada; although longer follow-up is warranted, the results show that treatment can provide improvement of mild-to-severe disease in typical clinical practice. |

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by well-demarcated, red, and scaly plaques that commonly appear on the knees, elbows, trunk, and scalp [1,2,3]. In the USA and Canada, the condition affects approximately 3.0% of the adult population [4, 5]. Being associated with itching, pain, and comorbidities such as psoriatic arthritis (PsA), anxiety, and depression, psoriasis can lead to significant disability that impacts patients’ daily activities and the ability to work [1, 6, 7]. Evidence indicates that as the severity of the disease increases, patients experience a worsening of clinical symptoms, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and work productivity [8, 9], although even mild or moderate disease can negatively impact patient well-being [9, 10].

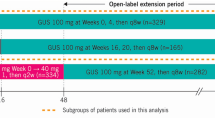

Guselkumab (Janssen Biotech, Inc., Horsham, PA, USA) is a fully human monoclonal antibody that blocks the p19 subunit of interleukin 23 (IL-23), a cytokine involved in the differentiation and survival of T cells that play a key role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis [11]. Two pivotal, randomized, phase III clinical trials, VOYAGE 1 (NCT02207231) and VOYAGE 2 (NCT02207244), led to approval of guselkumab in 2017 by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy [12]. In these trials, treatment with guselkumab was associated with superior responses on several Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) and Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) outcomes compared with placebo and the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonist adalimumab [13, 14]. Guselkumab therapy was well tolerated in both trials and improvements were also observed in numerous patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs), including the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) [13,14,15]. Long-term, open-label evaluation of guselkumab has shown durability of the therapy’s efficacy through 5 years of follow-up [16,17,18,19]. Benefits with guselkumab have also been shown among inadequate responders to ustekinumab (an IL-12/23 inhibitor) in the phase III NAVIGATE trial [20] and compared with secukinumab (an IL-17A inhibitor) in the phase III ECLIPSE trial [21]. In 2020, the therapy was approved by the FDA for the treatment of adults with active PsA [12] on the basis of the results of the phase III DISCOVER-1 (NCT03162796) and DISCOVER-2 (NCT03158285) trials [22, 23]. Guselkumab has also received approval for the treatment of psoriasis and PsA from Health Canada [24].

Real-world data can provide valuable insights on the experience of patients who would typically be excluded from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) as they would not meet study eligibility criteria. Several recent studies have evaluated the real-world effectiveness and safety of guselkumab in psoriasis, showing favorable outcomes on the PASI and a limited number of other disease activity assessments and PROMs [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. However, most of these investigations included patients with moderate-to-severe disease, had relatively short durations of treatment, evaluated few endpoints, and/or included populations located outside of the USA and Canada. As such, the objective of the current study was to assess the effectiveness of guselkumab after 9–12 months of persistent use among patients with plaque psoriasis and an IGA score ≥ 2 (indicating mild or greater severity) who were enrolled in the CorEvitas (formerly Corrona) Psoriasis Registry. Given the results of the VOYAGE trials and other regional real-world studies, it was hypothesized that patients who received guselkumab would exhibit improvements in both disease activity outcomes and PROMs after 9–12 months of persistent treatment.

Methods

Data Source

Study data were derived from the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry, an independent, multicenter, non-interventional registry. As described previously [40], this observational registry was launched in April 2015 in collaboration with the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) and prospectively captures data for patients who meet the following criteria: ≥ 18 years of age, diagnosis of psoriasis from a dermatologist, willing and able to provide written informed consent for registry participation, and started on or switched to an eligible psoriasis therapy (FDA-approved biologics and non-biologic systemics) at enrollment or within the 12 months before enrollment. Registry methods have been published elsewhere [40]; briefly, information for on-treatment effectiveness and PROMs is collected from both dermatologists and patients at the time of enrollment and subsequent outpatient clinical encounters that occur at approximately 6-month intervals.

Study Population

The study data included information from patients with CorEvitas visits occurring between 18 July 2017 (the approval date for guselkumab) and 10 July 2019 (the latest data cut at the time of the analysis). Patients were included if they met the following criteria: diagnosis of psoriasis with plaque morphology, initiated guselkumab at or after registry enrollment during a registry visit (defined as the index date) with an IGA score ≥ 2 (i.e., mild or greater disease severity) at that time, received persistent treatment with guselkumab for ≥ 9 months after the index date, and had a follow-up registry visit between 9 and 12 months after the index date. Patients who initiated guselkumab at a time between registry visits were excluded from the study to ensure that baseline characteristics and subsequent treatment-related changes were appropriately captured. If patients had more than one visit within the 9-to-12–month follow-up window, data were used from the visit closest to 12 months to consider the longest follow-up possible.

Study Outcomes

At the index and follow-up visits, the following measures were collected: IGA, PASI, body surface area (BSA), DLQI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI), EuroQoL visual analog scale (EQ-VAS), fatigue, skin pain, overall itch, and Patient Global Assessment (PGA) of psoriasis. The primary outcome was achievement of an IGA response of 0/1 (clear/almost clear skin) at the follow-up visit. Secondary disease activity outcomes included achievement of IGA 0, achievement of PASI 75, PASI 90, and PASI 100 (i.e., ≥ 75%, ≥ 90%, and 100% reductions, respectively, in PASI score from baseline to follow-up), and mean change in percent BSA. Secondary PROMs included achievement/maintenance of DLQI 0/1 and mean changes in DLQI, WPAI measures, EQ-VAS, PGA, fatigue, skin pain, and overall itch. These disease activity outcomes and PROMs have been described previously [9, 41]. Briefly, the IGA score categorizes levels of skin induration, scaling, and redness on a scale of 0 (clear) to 4 (severe) [42]. Percent total BSA reflects measurement of affected skin [43,44,45]. PASI quantifies the extent and severity of psoriasis, with scores ranging from 0 (no disease) to 72 (maximal disease severity) [2]. Achievement of PASI 90 means that a ≥ 90% reduction in the severity and body area affected by psoriasis has occurred. The DLQI is a validated, disease-specific measure of HRQoL that includes ten questions classified within six domains related to symptoms, feelings, activities, relationships, and treatment [46]. Respondents provide the degree to which they experienced problems on a 4-point Likert scale (0–4); a score of 0/1 indicates that psoriasis has no effect on a patient’s life. The WPAI measures the impact of psoriasis on a patient’s ability to work and overall activities [47]. The tool assesses the percent of work hours missed, percent of impairment while working, percent of work hours affected, and percent of daily activities impaired; responses for the three work domains are only valid if the respondent is currently employed. The EQ-VAS evaluates non-disease-specific HRQoL on a scale of 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state) [48]. Finally, patient-reported fatigue, skin pain, overall itch, and PGA [49] are also measured on a VAS of 0 to 100 (VAS-100), with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms or higher disease activity.

Other Variables

At the index visit, the study assessed a variety of baseline demographics and disease characteristics. Patient demographics and socioeconomic characteristics included age, sex, race/ethnicity, health insurance type, education, and work status, as well as lifestyle factors such as smoking status and body mass index (BMI, in kg/m2). Patients’ comorbidity scores were calculated using a version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [50] that was modified as the unweighted sum of current and prior physician-reported comorbidities ascertained by the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry: myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease (stroke or transient ischemic attack), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, history of peptic and/or gastrointestinal bleeding ulcer, diabetes mellitus, leukemia, lymphoma, solid tumor cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer), and liver disease. Comorbidities not captured by the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry and thus excluded from the modified CCI included dementia, kidney disease, hemiplegia, connective tissue disease, and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Disease characteristics were captured related to psoriasis morphology history and duration, as well as PsA diagnosis and duration and Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) score. Guselkumab-related treatment characteristics were also documented, including duration of therapy, concomitant psoriasis therapy at guselkumab initiation (systemic, topical, phototherapy), general biologic and non-biologic systemic therapy experience, and the frequency of use of specific agents before reception of guselkumab.

Data Analysis

All analyses were performed using Stata Release 15 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA). Descriptive statistics at the index visit were calculated for all variables. Counts (n) and frequencies (%) were calculated for categorical variables, and means and standard deviations (SD) were calculated for continuous variables.

For the primary (IGA 0/1) and secondary (IGA 0; PASI 75, 90, 100) dichotomous response outcomes (i.e., achieved/did not achieve), the percent of patients who had achieved the response at the follow-up visit was calculated along with the 95% confidence interval (CI). Analysis of the secondary outcome DLQI 0/1 included patients with a DLQI of 0 or 1 at guselkumab initiation; the percentage and 95% CI of patients who either maintained or achieved DLQI 0/1 at follow-up were calculated. For the secondary outcomes of changes in IGA, PASI, BSA, DLQI, WPAI, EQ-VAS, PGA, fatigue, skin pain, and overall itch, mean changes and 95% CIs were calculated from index to follow-up among patients with data at both visits. Paired t-tests were conducted to determine whether the mean changes in these outcomes were statistically different from zero (α = 0.05).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry and its investigators were reviewed and approved by a central institutional review board (IRB; IntegReview, Corrona-PSO-500). For academic investigative sites that did not receive a waiver to use the central IRB, full board approval was obtained from the respective governing IRBs. All registry participants were required to provide written informed consent and authorization prior to participation. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Results

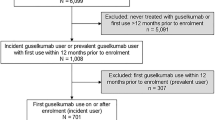

Between 18 July 2017 and 10 July 2019, a total of 1031 patients with plaque psoriasis were identified who had initiated guselkumab at or after enrollment in the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry (Fig. 1). Of these patients, 313 were persistently treated with guselkumab for at least 9 months and 206 had a follow-up registry visit that occurred between 9 and 12 months after the index date. In the latter group, 140 patients had initiated guselkumab at a registry visit and a total of 130 had an IGA score ≥ 2; these patients comprised the population for analysis.

Baseline Demographics

Among the 130 included patients, the mean (SD) age was 50.2 (13.8) years and 51 patients (39.2%) were female (Table 1). Most patients were white (72.3%), had private health insurance (70.0%), and worked full time (68.5%). Mean BMI was 32.7 kg/m2 (7.8), with most patients categorized as overweight (27.7%) or obese (56.9%). Over 50% of patients were current or former smokers. The most common baseline comorbidities were history of hypertension (35.4%), hyperlipidemia (25.4%), infection (20.8%), diabetes mellitus (16.2%), depression (16.2%), or anxiety (15.4%). The mean modified CCI score was 0.3 (0.6), with most patients (73.9%) having a score of 0.

Disease Characteristics

The mean (SD) duration of time since diagnosis of psoriasis was 17.5 years (13.4) (Table 2). Psoriasis morphology histories most frequently included scalp (31.5%), nail (10.0%), palmoplantar (9.2%), and/or inverse/intertriginous (5.4%) disease. A total of 37% of patients had PsA that was diagnosed by a dermatologist; 19.2% had rheumatologist-confirmed PsA. The mean duration of PsA was 10.9 (11.7) years and 26.4% of patients had a PEST score ≥ 3.

Most patients had received at least one previous biologic agent (79.2%) and/or at least one previous oral systemic agent (88.5%) (Table 2). The most common biologic and oral systemic medications used at any time before initiation of guselkumab were ustekinumab (50.8% of patients), adalimumab (48.5%), etanercept (33.9%), methotrexate (32.3%), apremilast (29.2%), secukinumab (23.2%), and ixekizumab (16.2%). During treatment with guselkumab, 6.9% of patients received concomitant systemic therapy, 42.3% received concomitant topical agents, and 2.3% of patients received phototherapy.

At the index visit, mean (SD) IGA score was 3.0 (0.6); 20.0% of patients had a score of 2 and 61.5% had a score of 3, indicating mild and moderate disease severity, respectively (Table 2). Mean percent BSA involvement was 12.4 (10.4); 6.9% of patients had scores reflecting mild disease (0 to < 3% BSA), 51.5% had scores reflecting moderate disease (3–10%), and 41.5% had scores reflecting severe disease (> 10%). Mean PASI score was 9.9 (7.7) and 40.8% of patients had a score > 10. In baseline HRQoL assessments, mean DLQI score was 8.0 (6.0), with approximately one-third of patients (31.5%) reporting that their psoriasis had a moderate impact on their life (score 6–10). On the WPAI, 74.6% of patients indicated they were currently employed; among these patients, the mean percent of work hours missed was 4.4% (15.7), impairment while working was 17.7% (24.5), and work hours affected was 19.0% (25.7). Across all patients, the mean percent daily activities affected was 22.7% (27.3). On the EQ-VAS and PGA, mean scores were 73.4 (19.7) and 50.4 (27.7); mean VAS-100 scores for fatigue, skin pain, and overall itch, were 33.9 (30.1), 34.9 (32.2), and 54.1 (33.5), respectively.

Primary Outcome: IGA 0/1

Among the 130 patients analyzed, 64.6% (95% CI 56.1, 72.3; n = 84) achieved an IGA score of 0/1 at their follow-up visit between 9 and 12 months, indicating their skin was clear or almost clear (Fig. 2).

Percentages of patients achieving IGA, PASI, and DLQI outcomes after 9–12 months of persistent use of guselkumab. N = 130 for all outcomes. Vertical bars represent 95% CIs. aPrimary study endpoint. bMaintained or achieved CI confidence interval, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, PASI Psoriasis Area Severity Index

Secondary Outcomes: Response Rates

At the time of the follow-up visit, an IGA score of 0 (clear) was achieved by 36.2% of patients (95% CI 28.4, 44.7; n = 47) (Fig. 2). PASI 75 was achieved by 61.5% of patients (95% CI 53.0, 69.5; n = 80), PASI 90 by 46.9% (95% CI 38.6, 55.5; n = 61), and PASI 100 by 36.9% (95% CI 29.1, 45.5; n = 48). More than half of patients (55.4%, 95% CI 46.8, 63.7; n = 72) had maintained or achieved DLQI 0/1, indicating that psoriasis had no effect on their life.

Secondary Outcomes: Changes at Follow-Up Versus Index Visit

From the index visit to follow-up, all mean (SD) changes in disease activity scores showed improvements that were statistically significantly greater than zero: IGA score decreased by 1.8 (1.1), PASI score decreased by 7.6 (7.0), and BSA decreased by 9.5 (9.1) (all P < 0.001; Fig. 3). For the PROMs, DLQI score decreased by a mean of 5.1 (5.9) (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4). WPAI results showed that among employed patients, work hours missed because of psoriasis decreased by 2.4% (12.9) (P = 0.122), impairment while working decreased by 12.0% (21.6), and work hours affected decreased by 12.4% (22.0); across all patients, daily activities affected by psoriasis decreased by 13.8% (26.0) (all P < 0.001). Outcomes measured on the VAS-100 also showed statistically significant improvements: EQ-VAS increased by a mean of 5.5 (18.8) (P = 0.009) and mean decreases were observed in scores for patient-reported fatigue, skin pain, and overall itch of 6.5 (26.0) (P = 0.041), 22.8 (29.7), and 31.6 (34.9) (both P < 0.001), respectively. PGA scores also decreased significantly by 28.0 (34.5) (P < 0.001).

Mean changes in disease activity outcomes between index and follow-up visits after 9–12 months of persistent use of guselkumab. **P < 0.001. N = 130 for all outcomes. Vertical bars represent standard deviations. Δ indicates the mean change (95% CI) in values between the index and follow-up visits; improvements are indicated by negative values. P-values reflect the results of paired t-tests of the mean change in outcomes from zero (α = 0.05). BSA body surface area, CI confidence intervals, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, PASI Psoriasis Area Severity Index

Mean changes in PROMs between index and follow-up visits after 9–12 months of persistent use of guselkumab. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001. Vertical bars represent standard deviations. Data are only presented for patients with values at both index and follow-up visits. Δ indicates the mean change (95% CI) in values between the index and follow-up visits; improvements are reflected by negative values for all outcomes except the EQ-VAS. P-values reflect the results of paired t-tests of the mean change in outcomes from zero (α = 0.05). CIs confidence intervals, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, EQ-VAS EuroQoL 5-dimension visual analog scale, PGA patient global assessment, PROMs patient-reported outcomes measures, PsO psoriasis, VAS visual analog scale, WPAI work productivity and activity impairment

Discussion

In this real-world study of patients with plaque psoriasis and a baseline IGA score ≥ 2 enrolled in the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry, 9–12 months of persistent treatment with guselkumab was associated with mean improvements in all evaluated outcomes, including both measures of disease activity outcomes (IGA, PASI, BSA) and PROMs (DLQI, WPAI, EQ-VAS, PGA, fatigue, skin pain, overall itch). To our knowledge, this study is one of the first analyses of the real-world effectiveness of guselkumab among patients located in the USA and Canada with plaque psoriasis of mild, moderate, or severe IGA disease severity. Although guselkumab is currently indicated in these regions for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [12, 24], an evaluation that includes patients with milder disease severity on the IGA may reflect real-world utilization of biologic therapies. Given there is usually no formal wash-out period between switching medications, the severity of psoriasis presentation at the time of biologic therapy initiation varies widely in typical clinical practice [51]. Accordingly, the broader population evaluated in the current study is likely more representative of patients who receive treatment in the real-world setting than those treated in clinical trials, which include highly selected patient populations [52].

In addition to having evaluated patients with a broad range of psoriasis IGA severities, this study is unique compared with most other real-world analyses of guselkumab in that it included prospectively collected data, assessed a larger number of patients, had a longer treatment duration, and/or evaluated a more comprehensive panel of disease activity scores and PROMs [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Previous studies have typically been retrospective analyses of patients who received guselkumab for ≤ 28 weeks and primarily focused on PASI outcomes—none appear to have reported on IGA, WPAI, or EQ-VAS scores or changes in several disease-specific symptoms. Although one Canadian study included patients receiving guselkumab for a mean of 1.2 years (range 0.2–2.7 years), it focused on moderate-to-severe disease and was limited to evaluation of changes in BSA and safety outcomes [29]. Other recent North America-based registry studies of guselkumab have focused on baseline demographics and disease characteristics, not the impact of therapy on disease activity and PROMs [51, 53].

Some variations in patient demographics and disease characteristics are observed between the patients in this registry study and those included in other real-world evaluations of guselkumab. In comparison to five previous studies that included > 50 patients and assessed durations of guselkumab therapy that were similar to that used in the current analysis (≥ 28 weeks–1.2 years) [27, 29,30,31, 39], mean patient age (50.2 years in CorEvitas versus 46.5–54 years) and psoriasis duration (17.5 versus 17.4–22.1 years) were generally in alignment; however, BMI (32.7 versus 28.0–29.9 kg/m2) was slightly higher among the CorEvitas registry patients. Additionally, the range of the proportions of female (39.2% versus 22.0–51.7%) and biologic-naïve (20.8% versus 9.1–48.8%) patients and mean baseline scores for PASI (9.9 versus 13.7–20.0) and BSA (12.4 versus 17.9–27.5) were relatively wide across other studies reporting these data. The number of effectiveness outcomes evaluated and their results also vary across the current registry analysis and other real-world studies [27, 29,30,31, 39]. In an Italian retrospective database study (N = 52), relatively high PASI 75, 90, and 100 responses (84.2%, 78.9%, and 63.2%, respectively) were reported at 52 weeks [30]; similar results were reported at 36 weeks in a study of Spanish patients [approximately 100%, 75%, and 60% (values were reported graphically); N = 55] [39]. The differences in PASI results between these studies and those in the current analysis likely arise from variations in baseline BMI, the proportion of biologic naïve patients, comorbidities, duration of follow-up/therapy, and/or other factors recognized to impact the response to treatment [54,55,56,57,58,59]. Other larger real-world studies have reported PASI findings that are more comparable to those found in the current CorEvitas population: PASI 75 and 90 responses were 67% and 37%, respectively, at 36 weeks in a retrospective, multicenter study of Taiwanese patients (N = 135) [31], while a German study (N = 303) reported responses of 76.7%, 55.3%, and 58.9% for PASI 75, 90, and 100 at 28 weeks of guselkumab therapy [27]. Similar to the current analysis, the Spanish study also showed statistically significant improvements in BSA, DLQI, and VAS pruritus (itching) from baseline to week 4 that were maintained through week 36 [39]. Additionally, the aforementioned single-center Canadian study (N = 79) reported that among patients with a mean of 1.2 years of guselkumab therapy, a BSA of 0% (clear) or < 1% (almost clear) was achieved by 44.2% and 29.1% of patients, respectively, at their most recent clinical evaluation [29].

Notably, in the current study, it was observed that the number of patients who achieved IGA 0 (n = 47) and PASI 100 (n = 48) was not identical. Although unexpected, this small difference may be explained by the fact that these measures were scored independently of one another by a dermatologist. Such inconsistency may reflect the subjective nature of these measures and differences and/or limitations in their ability to precisely quantify disease activity.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, such as inclusion of patients with a psoriasis disease severity of IGA ≥ 2 at baseline, which may align more accurately with typical clinical practice. Furthermore, the study considered a longer guselkumab treatment duration than those included in most other real-world studies and evaluated numerous disease severity outcomes and PROMs that are important for understanding changes in patient well-being and functioning during treatment. Although the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry collects both retrospective and prospective data (see Methods section), the current analysis was conducted using prospectively captured data, which potentially addresses confounding related to recall bias. To our knowledge, this is the only study to evaluate the real-world impact of guselkumab among patients located in both the USA and Canada. Still, given this was an analysis of registry data, some limitations related to observational studies should be considered. This study focused on patients who received persistent treatment with guselkumab, which may limit the generalizability of the results to all guselkumab-treated patients. In addition, although characterization of reasons for treatment discontinuation was beyond the scope of this study, lack of treatment effectiveness was likely a prominent driver. Exclusion of these individuals may have led to overestimation of the impact of guselkumab. Additionally, not all patients who received persistent guselkumab treatment had a follow-up visit at 9–12 months, leading to exclusion of a considerable number of patients (107 of 313). Some registry patients may have fit all study criteria but had less severe disease (IGA < 2) and were excluded. At the time of study conceptualization, it was thought that analysis of such patients would be inappropriate, given they are unlikely to reflect individuals typically receiving guselkumab. Such individuals may present with unusual baseline and/or disease characteristics that may prompt biologic use yet could skew the overall study results. Another limitation of the study was that up to 42.3% of patients received concomitant therapy (e.g., topical agents), which may have impacted the magnitude of the clinical outcomes. As the study was a non-comparative, single-arm analysis of persistent guselkumab use, data for the last biologic therapy received before guselkumab were not captured. The authors recognize that understanding outcomes in the context of specific prior biologic therapy may be of interest, but such analysis was beyond the scope of the study; future investigation is warranted. Similarly, analysis of drug survival may also be of interest; however, this was not performed given the study’s objective was to understand outcomes related to persistent guselkumab therapy. Finally, given that the CorEvitas registry only includes US and Canadian patients and that patients and dermatologists voluntarily participate, the results may be prone to selection bias and may not be generalizable to other patients in these regions or in other countries.

Conclusions

This study of data from the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry evaluated the effectiveness of persistent guselkumab therapy among patients located in the USA and Canada who had plaque psoriasis with IGA disease severity ≥ 2. The results show that 9–12 months of guselkumab treatment is associated with meaningful improvements in numerous assessments of disease activity and PROMs in a broad, real-world psoriasis patient population. Longer-term analysis of data from the CorEvitas registry and other sources, as well as additional assessments in various psoriasis patient subpopulations, will further improve the understanding of the real-world effectiveness of guselkumab.

References

Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Molec Sci. 2019;20(6):1475.

Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, Kivelevitch D, Prater EF, Stoff B, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1029–72.

Boehncke WH, Schon MP. Psoriasis Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983–94.

Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, Gondo GC, Bell SJ, Griffiths CEM. Psoriasis prevalence in adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(8):940–6.

Papp KA, Gniadecki R, Beecker J, Dutz J, Gooderham MJ, Hong CH, et al. Psoriasis prevalence and severity by expert elicitation. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(3):1053–64.

Martínez-Ortega JM, Nogueras P, Muñoz-Negro JE, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, González-Domenech P, Gurpegui M. Quality of life, anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with psoriasis: a case-control study. J Psychosom Res. 2019;124:109780.

Orbai AM, Reddy SM, Dennis N, Villacorta R, Peterson S, Mesana L, et al. Work absenteeism and disability associated with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the USA-a retrospective study of claims data from 2009 TO 2020. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(12):4933–42.

Korman NJ, Zhao Y, Pike J, Roberts J. Relationship between psoriasis severity, clinical symptoms, quality of life and work productivity among patients in the USA. Clin Exper Dermatol. 2016;41(5):514–21.

Strober B, Greenberg JD, Karki C, Mason M, Guo N, Hur P, et al. Impact of psoriasis severity on patient-reported clinical symptoms, health-related quality of life and work productivity among US patients: real-world data from the Corrona Psoriasis Registry. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4):e027535.

Salman A, Yucelten AD, Sarac E, Saricam MH, Perdahli-Fis N. Impact of psoriasis in the quality of life of children, adolescents and their families: a cross-sectional study. An Bra Dermatol. 2018;93(6):819–23.

Teng MWL, Bowman EP, McElwee JJ, Smyth MJ, Casanova J-L, Cooper AM, et al. IL-12 and IL-23 cytokines: from discovery to targeted therapies for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Nat Med. 2015;21(7):719–29.

FDA. Food and Drug Administration. TREMFYA (guselkumab) Injection 2020 [updated 07/2020. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761061s007lbl.pdf.

Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, Randazzo B, Wasfi Y, Shen YK, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: results from the phase III, double-blinded, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):405–17.

Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P, Song M, Wasfi Y, Randazzo B, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: results from the phase III, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):418–31.

Armstrong AW, Reich K, Foley P, Han C, Song M, Shen YK, et al. Improvement in patient-reported outcomes (Dermatology Life Quality Index and the Psoriasis Symptoms and Signs Diary) with guselkumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results from the Phase III VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2 studies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(1):155–64.

Reich K, Griffiths CEM, Gordon KB, Papp KA, Song M, Randazzo B, et al. Maintenance of clinical response and consistent safety profile with up to 3 years of continuous treatment with guselkumab: results from the VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2 trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(4):936–45.

Blauvelt A, Gordon KB, Griffiths CEM, Papp KA, Foley P, Song M, et al. Long-term safety of guselkumab: results from the VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2 trials with up to 5 years of treatment J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(3):Supplement AB174.

Griffiths CEM, Papp KA, Song M, Miller M, You Y, Shen YK, et al. Continuous treatment with guselkumab maintains clinical responses through 4 years in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from VOYAGE 1. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1–9.

Reich K, Gordon KB, Strober BE, Armstrong AW, Miller M, Shen YK, et al. Five-year maintenance of clinical response and health-related quality of life improvements in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis treated with guselkumab: results from VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185(6):1146–59.

Langley RG, Tsai TF, Flavin S, Song M, Randazzo B, Wasfi Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis who have an inadequate response to ustekinumab: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III NAVIGATE trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(1):114–23.

Reich K, Armstrong AW, Langley RG, Flavin S, Randazzo B, Li S, et al. Guselkumab versus secukinumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis (ECLIPSE): results from a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10201):831–9.

Deodhar A, Helliwell PS, Boehncke WH, Kollmeier AP, Hsia EC, Subramanian RA, et al. Guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis who were biologic-naive or had previously received TNFα inhibitor treatment (DISCOVER-1): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1115–25.

Mease PJ, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, Kollmeier AP, Hsia EC, Xu XL, et al. Guselkumab in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (DISCOVER-2): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1126–36.

Health Canada. Product Monograph Including Patient Medication Information. TREMFYA (guselkumab injection) 2021 [updated 17 Sept 2021. Available from: https://produits-sante.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/info.do?lang=en&code=97748.

Snast I, Sherman S, Holzman R, Hodak E, Pavlovsky L. Real-life experience of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6): e13964.

Schwensen JFB, Nielsen VW, Nissen CV, Sand C, Gniadecki R, Thomsen SF. Effectiveness and safety of guselkumab in 50 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who had previously been treated with other biologics: a retrospective real-world evidence study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(5):e341–3.

Gerdes S, Bräu B, Hoffmann M, Korge B, Mortazawi D, Wiemers F, et al. Real-world effectiveness of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis: health-related quality of life and efficacy data from the noninterventional, prospective. German multicenter PERSIST trial J Dermatol. 2021;48(12):1854–62.

Chan Y, Tong BSB, Ngan PY, Au CS. Effectiveness of IL-23 inhibitor guselkumab in real-world Chinese patients with psoriasis during a 20-week period. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2021;11:53–8.

Maliyar K, O’Toole A, Gooderham MJ. Long-term single center experience in treating plaque psoriasis with guselkumab. J Cutan Med Surg. 2020;24(6):588–95.

Galluzzo M, Tofani L, Lombardo P, Petruzzellis A, Silvaggio D, Egan CG, et al. Use of guselkumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a 1 year real-life study. J Clin Med. 2020;9(7):2170.

Hung YT, Lin YJ, Chiu HY, Huang YH. Impact of previous biologic use and body weight on the effectiveness of guselkumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a real-world practice. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211046684.

Del Alcázar E, López-Ferrer A, Martínez-Doménech Á, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Del Mar Llamas-Velasco M, Rocamora V, et al. Effectiveness and safety of guselkumab for the treatment of psoriasis in real-world settings at 24 weeks: a retrospective, observational, multicentre study by the Spanish Psoriasis Group. Dermatol Ther. 2021:e15231.

Ruggiero A, Fabbrocini G, Cinelli E, Ocampo Garza SS, Camela E, Megna M. Anti-interleukin-23 for psoriasis in elderly patients: guselkumab, risankizumab and tildrakizumab in real-world practice. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021.

Malara G, Trifirò C, Bartolotta A, Giofré C, D’Arrigo G, Testa A, et al. Real-world effectiveness and safety of guselkumab for the treatment of psoriasis: a 6-month prospective study in a series of psoriatic patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(1):406–12.

Bonifati C, Morrone A, Cristaudo A, Graceffa D. Effectiveness of anti-interleukin 23 biologic drugs in psoriasis patients who failed anti-interleukin 17 regimens. A real-life experience Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(1): e14584.

Zhuang J-Y, Li J-S, Zhong Y-Q, Zhang F-F, Li X-Z, Su H, et al. Evaluation of short-term (16-week) effectiveness and safety of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis: a prospective real-life study on the Chinese population. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(5): e15054.

Benhadou F, Ghislain PD, Guiot F, Willaert F, Del Marmol V, Lambert J, et al. Real-life effectiveness and short-term (16-week) tolerance of guselkumab for psoriasis: a Belgian retrospective multicentre study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(12):e837–9.

Fougerousse AC, Ghislain PD, Reguiai Z, Maccari F, Parier J, Bouilly Auvray D, et al. Effectiveness and short-term (16-week) tolerance of guselkumab for psoriasis under real-life conditions: a retrospective multicenter study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(10):e644–6.

Rodriguez Fernandez-Freire L, Galán-Gutierrez M, Armario-Hita JC, Perez-Gil A, Ruiz-Villaverde R. Guselkumab: short-term effectiveness and safety in real clinical practice. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(3): e13344.

Strober B, Karki C, Mason M, Guo N, Holmgren SH, Greenberg JD, et al. Characterization of disease burden, comorbidities, and treatment use in a large, US-based cohort: results from the Corrona Psoriasis Registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(2):323–32.

Spuls PI, Lecluse LLA, Poulsen M-LNF, Bos JD, Stern RS, Nijsten T. How good are clinical severity and outcome measures for psoriasis?: Quantitative evaluation in a systematic review. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(4):933–43.

Langley RG, Feldman SR, Nyirady J, van de Kerkhof P, Papavassilis C. The 5-point Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scale: a modified tool for evaluating plaque psoriasis severity in clinical trials. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(1):23–31.

Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Wu J, Bebo B. Quality of life and work productivity impairment among psoriasis patients: findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation survey data 2003–2011. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12): e52935.

Horn EJ, Fox KM, Patel V, Chiou CF, Dann F, Lebwohl M. Association of patient-reported psoriasis severity with income and employment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(6):963–71.

Pariser DM, Bagel J, Gelfand JM, Korman NJ, Ritchlin CT, Strober BE, et al. National Psoriasis Foundation clinical consensus on disease severity. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(2):239–42.

Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–6.

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–65.

EuroQoL Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208.

Bożek A, Reich A. The reliability of three psoriasis assessment tools: psoriasis area and severity index, body surface area and physician global assessment. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26(5):851–6.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Walsh JA, Callis Duffin K, Van Voorhees AS, Chakravarty SD, Fitzgerald T, Teeple A, et al. Demographics, disease characteristics, and patient-reported outcomes among patients with psoriasis who Initiated guselkumab in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(1):97–119.

Blonde L, Khunti K, Harris SB, Meizinger C, Skolnik NS. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 2018;35(11):1763–74.

Fitzgerald T, Teeple A, Slaton T, Kozma CM. Characteristics of patients initiating guselkumab for plaque psoriasis in the Symphony Health Claims database. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20(10):1127–31.

Papp KA, Gordon KB, Langley RG, Lebwohl MG, Gottlieb AB, Rastogi S, et al. Impact of previous biologic use on the efficacy and safety of brodalumab and ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: integrated analysis of the randomized controlled trials AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(2):320–8.

Gottlieb AB, Lacour JP, Korman N, Wilhelm S, Dutronc Y, Schacht A, et al. Treatment outcomes with ixekizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who have or have not received prior biological therapies: an integrated analysis of two phase III randomized studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(4):679–85.

Edson-Heredia E, Sterling KL, Alatorre CI, Cuyun Carter G, Paczkowski R, Zarotsky V, et al. Heterogeneity of response to biologic treatment: perspective for psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(1):18–23.

Enos CW, Ramos VL, McLean RR, Lin T-C, Foster N, Dube B, et al. Comorbid obesity and history of diabetes are independently associated with poorer treatment response to biologics at 6 months: a prospective analysis in Corrona Psoriasis Registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(1):68–76.

Cassano N, Galluccio A, De Simone C, Loconsole F, Massimino SD, Plumari A, et al. Influence of body mass index, comorbidities and prior systemic therapies on the response of psoriasis to adalimumab: an exploratory analysis from the APHRODITE data. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2008;22(4):233–7.

Kisielnicka A, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Nowicki RJ. The influence of body weight of patients with chronic plaque psoriasis on biological treatment response. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2020;37(2):168–73.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was sponsored by CorEvitas, LLC. The analysis and all manuscript-related activities (including payment of the journal’s Rapid Service Fee) were funded by Janssen Biotech, Inc.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

The authors wish to thank Dana L. Anger of WRITRIX Medical Communications Inc. and Dr. Ari Mendell of EVERSANA for their support in the development of this manuscript, which was funded by Janssen Biotech, Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

RRM, TF, and AT were responsible for study conception and design. RRM, YS, and LG were responsible for acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. All authors were responsible for drafting the manuscript as well as critically revising/reviewing the manuscript and providing final approval.

Disclosures

In the last two years, CorEvitas has been supported through contracted subscriptions from AbbVie, Amgen, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Chugai, Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, LEO, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer Inc., Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun, and UCB. The Psoriasis Registry was developed in collaboration with the NPF. Access to study data was limited to CorEvitas, and CorEvitas statisticians completed all of the analysis. A.W. Armstrong has served as a research investigator and/or scientific advisor to AbbVie, Almirall, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, ASLAN, Beiersdorf, BI, BMS, Dermavant, Dermira, EPI, Incyte, Janssen, Leo, Lilly, Modmed, Nimbus, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun, and UCB. K. Callis Duffin has been a consultant/advisor/advisory board member for Amgen/Celgene, AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, and Boehringer-Ingelheim and an investigator for AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Stiefel Laboratories, UCB, Ortho Dermatologics, Anaptys Bio, and Boehringer-Ingelheim. T. Fitzgerald, A. Teeple, K. Rowland, J. Uy, and M. Olurinde are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and stockholders of Johnson & Johnson, of which Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC is a wholly owned subsidiary. R.R. McLean, L. Guo, and Y. Shan are employees of CorEvitas LLC. EVERSANA is a paid consultant of Janssen and supported the writing and submission of this manuscript; WRITRIX Medical Communications Inc. is a subcontractor of EVERSANA.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The CorEvitas registry and its investigators were reviewed and approved by a central institutional review board (IRB; IntegReview, Corrona-PSO-500). For academic investigative sites that did not receive a waiver to use the central IRB, full board approval was obtained from the respective governing IRBs. All registry participants were required to provide written informed consent and authorization prior to participation. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as there were obtained through a commercial subscription agreement with CorEvitas, LLC.

Thanking Patient Participants

The authors would like to thank all the investigators, their clinical staff, and patients who participate in the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry.

Prior Presentation

Some components of the data reported in this manuscript were presented previously: Armstrong A, Callis-Duffin K, Fitzgerald T et al. (2021) 26,916 Effectiveness of guselkumab among patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry. J Am Acad Dermatol 85 AB122.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Armstrong, A.W., Fitzgerald, T., McLean, R.R. et al. Effectiveness of Guselkumab Therapy among Patients with Plaque Psoriasis with Baseline IGA Score ≥ 2 in the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 13, 487–504 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00865-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00865-0