Abstract

Early Mediaeval Archaeology was long influenced by traditional narratives related to so-called Völkerwanderungen. Based on the interpretation of ancient written sources, the “Migration Period” was traditionally perceived as a time of catastrophic changes triggered by the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and massive migration waves of “barbarian” groups across Europe. In the last decades, isotope analyses have been increasingly used to test these traditional narratives by exploring past mobility patterns, shifts in dietary habits, and changes in subsistence strategies or in socio-economic structures among early medieval societies. To evaluate the achievements of isotope studies in understanding the complexity of the so-called Migration Period, this paper presents a review of 50 recent publications. Instead of re-analysing the data per se, this review first explores the potentials and limitations of the various approaches introduced in the last decades. In a second step, an analysis of the interpretations presented in the reviewed studies questions to what extend traditional expectations are supported by isotope data from the Migration Period. Beside revising the concept of massive migrations, isotope data reveal so-far underestimated mobility patterns and open new perspectives in the investigation of early medieval world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The investigation of migration patterns is a fundamental issue in Early Mediaeval Archaeology, in particular because ancient written sources suggest that several presumably “barbarian groups” moved across Europe during the so-called Migration Period (Halsall 2005; Heather 2010). Depending on our modern interpretation of those texts, these movements were traditionally interpreted as invasions (Goffart 1989; Halsall 2005: 111–132) or as migrations (Halsall 2007: 13–22) and were usually associated with catastrophic scenarios (Graceffa 2008; Halsall 2014; Ward-Perkins 2005). The German term Völkerwanderung especially implies the massive migration of entire politically, socially, and culturally uniform groups, which replaced the local population (Goffart 2006; Halsall 2010; Heather 2018). This has been the prevailing conception in the field of European Late Antique and Early Mediaeval Archaeology between the nineteenth and the middle of the twentieth century (see Suppl. Text. 1A). Even though it has been acknowledge that an individual’s identity or ethnicity cannot be assessed solely based on material culture (Childe 1951: 30–40; Curta 2020; Lucy 2005), tenacious expectations and prejudices have long influenced the interpretation of early medieval archaeological records. The implications of an ethnic focus in Early Mediaeval Archaeology are exemplified in the supplement (Suppl. Text 1A).

In this context, and because the traditional archaeological approach fails to distinguish migration from other mobility patterns and other forms of the diffusion of material culture (Burmeister 2016; Lucy 2005), the application of bioarchaeological methods, including isotope—and recently also aDNA—analyses, has become a common tool to investigate early medieval mobility patterns. Stable isotope analyses provide proxies for dietary habits and mobility behaviour of individuals, which cannot be achieved with any traditional archaeological approach (see Suppl. Text 1B for a short description of the principles). Hence, it was first perceived as a ground-breaking method that would answer all questions. Now, the peak of inflated expectations and the trough of disillusionment are behind us on Gartner’s Hype Cycle (Gartner 2019) (Fig. 1), and this method has probably reached a position between the slope of enlightenment and the plateau of productivity—though new waves of innovations and improvements are constantly pushing the field forwards (Britton and Richards 2020; Kristiansen 2014; Martinón-Torres and Killick 2015).

Gartner’s Hype Cycle (Gartner 2019) including the concept of new waves of innovation—modified by M.L.C. Depaermentier

To better assess the potential and achievements of isotope analyses in Early Medieval Archaeology, it is important to know how the research has been performed. What are the aims of the studies? What proxies, samples and methods are used to answer specific research questions? What kind of information is made available? And how has it changed our perception of the so-called Migration Period? After overviews of the potentials and limitations of isotope analyses in archaeological research in general (Madgwick et al. 2021; Makarewicz and Sealy 2015; Pederzani and Britton 2019) and in Early Medieval Archaeology in particular (Hakenbeck 2013), and after a Europe-wide reconstruction of mobility patterns and dietary habits for the period between 500 and 1100 AD (Leggett 2021a, 2022), this paper aims at defining the current state of interdisciplinary research regarding mobility during the so-called Migration Period. Instead of conducting a new blind analysis of isotope data per se as in recent meta-analyses (Cocozza et al. 2022; Leggett 2022; Leggett et al. 2022), it critically reviews a set of 50 publications using strontium, oxygen, nitrogen and carbon isotope analyses to highlight advances in Early Medieval archaeological research based on isotope studies.

Material and methods

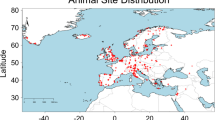

To evaluate the role of isotope studies in the new understanding of the so-called Migration Period, a random but representative set of 50 publications (Table 1, Fig. 2, Suppl. Tab. 1A) have been selected among the great number of recent publications (from 2000 onwards) specifically dealing with Völkerwanderungen and directly related to migration narratives. Studies using isotope data to exclusively investigate diet, subsistence strategies, trade, social structures or basic mobility patterns during the Early Middle Ages were therefore omitted.

Number of publications (blue font and circles) and minimum number of sites (orange font and circles) comprised in the selected dataset per modern country. Some sites are included in more than one publication but are still counted only once. (See Suppl. Tab. 1A for more details and Suppl. Tab. 1D for the counts in form of a table)

Chronologically, papers dealing with both the so-called Migration Period and the Viking (expansion) Period, which corresponds to a large span from the 5th to the 10th century AD, were selected. Some papers which included earlier or later comparative data to do a diachronic study (e.g. Cahill Wilson and Standish 2016; Fuller et al. 2010; Lightfoot et al. 2012; Varano et al. 2020) or which had no precise chronology (Quirós Castillo et al. 2012; Wilhelmson and Ahlström 2015)—hence larger than the investigated period—were also included in the corpus. However, only the sites dating in the so-called Migration Period were considered for the analyses at the site level.

Comprehensive datasets for this period are available in large-scale “big data” meta-analyses (Cocozza et al. 2022; Leggett 2022; Leggett et al. 2022) but due to the specific aims of this study, the redundancy in research design and the sometimes restricted access to publications, a smaller subset of recent publications can be considered representative of the general trends in this research field for the last c. two decades. A detailed description and further comments on the chronological and geographical framework of this corpus can be find in the supplement (Suppl. Text. 1C).

The concept of Völkerwanderungen can be defined as the expectation of massive migration events of smaller or larger groups of people (who did not necessarily correspond to ethnic groups as suggested by the German term, and who moved in general from northern, eastern or central Europe to western or southern Europe) based on the traditional interpretation of ancient written sources (Heather 2018). To assess to what extent isotope analyses can answer questions related Völkerwanderungen narratives and to verify if the traditional narratives are supported by the bioarchaeological records, information on research design and data interpretation were collected from the selected publications in an Excel sheet (see Suppl. Tab. 1A).

First, a comparison between the aims of the studies and the applied methods was used to evaluate the potential of the research design to answer addressed questions. In this context, the publications tracking mobility patterns and those tracking the impact of newcomers at the local scale were considered separately. Several aspects in the data results such as the various scales of attested mobility, information related to dietary habits and social structures as well as comparisons with the archaeological context were evaluated to assess what kind of mobility patterns are detected by means of isotope analyses. Then, the potentials and limits of assessing the impact of “Völkerwanderungen” was discussed. In a last step, new insights into early medieval societies provided by isotope studies were presented and discussed.

A detailed description of the data compilation and preparation is available in the Suppl. Text. 1D. To enable a systematic review, the collected information was standardised and reduced to a keyword-based table (see Suppl. Tab. 1B–C). A definition of these keywords is available in the Suppl. Tab. 2. Based on this set of information, the number of occurrences of each possible attribute within each variable was counted and represented in form of bar plots for qualitative data and in form of violin plots for quantitative data. The sample size limitations and the several cases for which information was missing (noted as “NA” in the supplementary tables) did not allow for pertinent statistical approaches. A graphical approach was thus used to highlight trends in the data. The paper is organised thematically, and a detailed description of its structure is available in the supplement (Suppl. Text. 1D).

Potential and limits of isotope analyses

In this set of publications, almost 75% (i.e. 37 publications) aim at directly investigating human mobility patterns, while the remaining 13 publications instead evaluate the impact of events such as the alleged arrival of “barbarian groups” or the collapse of the Roman Empire on local populations. Since these different goals intrinsically shape the research design and possible interpretations, both categories will be considered separately in this study (Fig. 3 (A)). A brief description of the potentials and limitations of the isotope systems used in the selected studies aims at discussing the suitability of this primary choice compared to the research question.

(A) Number of publications combining different isotope systems for reconstructing either human mobility patterns (referred to as “Migrations”) or the impact of newcomers or of the fall of Rome on local populations (referred to as “Impact”). Diet only: carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses. Geology and/or climate: strontium and/or oxygen (and sulphur or lead) isotope analyses. Diet and climate or geology: any combination of both previous isotope systems. (B) Number and proportion of publications using different isotope systems for exploring various aspects of early medieval societies in the “Migrations” or (C) “Impact” categories (see details in Suppl. Tab. 1A-B and the counts in table form in Suppl. Tab. 1E)

Tracking mobility

Among the studies which question the traditional migration narratives, the main research goals are dedicated to the identification of foreign individuals, the estimation of their origin and the correlation between foreign cultural attributes and foreign origin (Fig. 3 (B)). The evaluation of the scale of migration on the demographic and geographical level, the identification of a gendered mobility pattern and the impact of newcomers on local populations are further key questions (Suppl. Tab. 1B and 1E). And because 87Sr/86Sr (Evans et al. 2010; Montgomery 2010; Price et al. 2002) and/or δ18O (Lightfoot and O’Connell 2016; Pederzani and Britton 2019) isotope values reflect the local environmental and geographical settings in a more specific way than δ13C and δ15N values, this makes them more suitable for studying past mobility patterns and explains why they are used for 35 (i.e. 95%) publications dealing with the direct reconstruction of mobility patterns or migration events.

It is however important to stress that particularly δ18O isotope ratios but also 87Sr/86Sr values measured in human tissues provide ambiguous data (see also Suppl. Text 1B). In particular, due to the equifinality of such values and the problem of mixed values, these approaches benefit from complementary evidence to avoid underestimating the proportion of local individuals or get further information for the determination of origin for examples. In this context, it is noteworthy that strontium isotope analyses are frequently used as single proxy (Knipper et al. 2012; Ortega et al. 2013; Veselka et al. 2021). Nevertheless, an important (but not necessarily increasing) number of studies combine these environmental-based approaches with carbon and/or nitrogen analyses, which provides complementary information on diverse cultural aspects, the potential place of origin and different life stages (see below).

On the contrary, two publications apply only carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses for directly tracking mobility patterns (Hakenbeck et al. 2010; Plecerová et al. 2020). In this case, mobility might be overlooked if the diet of the migrants has no distinct isotopic values compared to the local diet. On the other hand, one should also consider all the other possible factors that could actually cause the observed isotope values (Makarewicz and Sealy 2015; van Klinken et al. 2000); otherwise, mobility might be overestimated. Consequently, even though dietary habits are an important part of cultural identity, a shift in diet is not direct evidence for mobility, especially because too many other environmental and cultural factors affect the δ13C and δ15N values (Makarewicz and Sealy 2015; van Klinken et al. 2000). Taken separately, this method seems therefore to be less suitable to trace mobility patterns.

Tracking the newcomer’s diet

On the other hand, most studies investigating the impact of newcomers on local population (i.e. 62%) were based exclusively on a dietary approach, which means on carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses (Fig. 3 (A)). For the Migration Period, the consumption of millet (a C4 plant) has frequently been assigned to some ethnic, social or religious groups (traditionally but mistakenly considered as entities (Brubaker 2002)) such as Slavs (Halffman and Velemínský 2015; Iacumin et al. 2014; Reitsema and Kozłowski 2013), Lombards (Alt et al. 2014; Maxwell 2019: XVI; Temkina 2021: 39–43), Muslims (Fuller et al. 2010) or more generally, to individuals from southern or eastern regions such as the Mediterranean (Crowder et al. 2020; Müldner 2013; Schuh and Makarewicz 2016). This means that depending on the context, a C4 signal (usually over − 18 ‰ in the δ13C values of human bone collagen (Alt et al. 2014; Lightfoot et al. 2015) is interpreted either as the presence of foreigners within a C3 plants ecosystem (Crowder et al. 2020; Müldner 2013; Schuh and Makarewicz 2016) or as a shift in the local diet or subsistence strategy due to the arrival of a foreign group (Hakenbeck et al. 2017; Iacumin et al. 2014; Lightfoot et al. 2012).

Since the consumption of millet or other C4 plants is one of the only changes in diet that one can quite clearly be observed by means of carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses, in most parts of Europe, newcomers might only be identified if they consumed C4 plants. It is therefore lucky that newcomers are mostly expected to come from regions where C4 plants were originally cultivated. However, the identification of C4 plants in the human diet is not always straightforward (see Suppl. Text 1B).

Moreover, aiming at verifying the impact of “barbarian migrations” and/or the so-called Fall of Rome on local populations first implies that Völkerwanderung narratives and related ethnic categorisation of the investigated burials are considered a valid background information. However, as stated above, this isotope system does not allow for determining the migration status of single individuals. Hence, this approach is certainly suitable to trace changes in dietary habits, subsistence strategies or further cultural aspects, but it remains difficult to ascertain whether such changes are related to the arrival of newcomers—especially if not combined with other isotope systems. Based on this single proxy, such research drivers and design might lead to a biased, agenda-driven (over)interpretation of isotope data (Hakenbeck 2013; Madgwick et al. 2021).

Meaning and representativity of isotope data

Narratives related to “Völkerwanderungen” usually imply the expectation of massive migrations—sometimes even of population replacement. In this context, the investigated burial community are often considered to equate (at least parts of) a given cultural group. Because it is essential to assess to what extent the sampled individuals and material were representative for past mobility and dietary patterns and to determine if they were representative for the predefined groups, the sampling strategies documented in the reviewed publications will be explored in terms of sample size, selection criteria and sampled material (see details in Suppl. Tab. 1A–C).

Sampled individuals

One key issue to assess sample representativity is to refer to the sample size. However, there is no universally “appropriate” number of sampled individuals since this primarily depends on the research question. For example, if the goal of the study is to reconstruct the life history of a single individual (Czére et al. 2021; Dutton 2018), a small sample size (even n = 1) is intrinsically justified. Moreover, if the total number of burials at the site is small, the sample size will be restricted accordingly (Fig. 4 (A)). Nonetheless, a small sample taken from a small burial ground is more likely to be representative for the burial community than a larger sample from a large cemetery, because it represents a larger proportion of the excavated individuals. In the selected dataset, the sample size varies between 1 and 182, with an average of about 30 individuals (Fig. 4 (B)). At this point, it is noteworthy that even if the sample size only depends on the size of the burial ground, the sample will still only reflect the investigated burial community and not necessarily the whole region or—if supposed to be investigated as such—a given ethnic or cultural group. It is however worth emphasising that not only the social (and ethnic) status (Brownlee 2021; Díaz-Andreu et al. 2005; Leggett and Lambert 2022) (see also Suppl. Text 1E) but also more fundamental issues such as sex, age, health and chronology are often difficult to assess without including scientific analyses (Grupe et al. 2012; Hines 2013; Katzenberg and Grauer 2018; Meier 2020). It is thus important to assess whether the definition of a group based on cultural, social or chronological criteria is reliable.

(A) Violin plot of the total number of burials known at each site—only for publications in which the information was directly available (n = 55 sites or research area). (B) Violin plots of the sample size at each site (or research area). In this case, the large sample sizes from large-scale, big-data studies (Leggett 2021a; Leggett et al. 2022) were not included in the violin plots because their scale is not comparable to the other sites or research areas (see Suppl. Text. 1A and Suppl. Tab. 1C for more details). (C) Number of publications per category which applied the various sampling strategies. Here, “restricted” represents the publications which mention only the restriction issues and no specific strategy. It is however noteworthy that almost every sample selection was restricted by material availability. (D) Number of samples at the various sites that represent a chronological span of a few decades up to four centuries or more

In many cases, the sample selection was more driven by material availability than by the research question. At least 33 publications (66%) mentioned that the sample selection was limited by the poor preservation or the lack of required material (Suppl. Tab. 1E). The research goal is certainly another important factor. Sampling every individual is hence not often possible or intended (Fig. 4 (C)). There are further attempts to select samples that reflect the diversity of the burial rites and possible social categories at each site. A random selection is however quite seldom (Suppl. Tab 1B). It is noteworthy that particularly studies from the category “impact” that test for a given group or attribute, often restricted the analysis to the individuals that meet these predefined criteria and only seldom included a comparison test sample. The possibility to evaluate the relationship between socio-cultural attribute and isotope composition appears restricted in such cases.

Regarding the chronology (Fig. 4 (D)), especially samples that span a considerable period are less likely to provide representative and robust results than samples related to a more precisely dated context. In this dataset, more than half of the samples (53%, i.e. 51 samples) are dated within a few decades or one century. The remaining half represents a chronological span at least two, in 21 cases (22%) even four or more centuries. The reliability of the interpretation might be compromised in such cases, especially when trying to seize a specific event.

Sampled material

Isotope analyses in archaeology are generally carried out on two main tissue categories. On the one hand, δ13C and δ15N ratios are measured in proteins such as bone or dentine collagen. On the other hand, 87Sr/86Sr, δ18O and δ13C are measured in the mineral part of the skeleton such as dental enamel or bone apatite. In any case, the building time and remodelling turnover of the tissues as well as their susceptibility to diagenetic alterations are key issues that drive the selection of the material. A detailed overview is available in the supplement (Suppl. Text 1B and F) as well as in the literature (Ambrose and Norr 1993; Bentley 2006; Lightfoot and O’Connell 2016; Pederzani and Britton 2019). The choice of different tissues is consequently particularly essential because the results will represent different parts of the diet, of the life history or of the environment.

To track mobility patterns

Because studies which directly investigate mobility patterns mostly apply strontium and/or oxygen isotope analyses, which are in general carried out on dental enamel, isotope data from this category are mainly reflecting the childhood and/or adolescence of the analysed individuals (Fig. 5 (A)). In most cases, only one tooth and hence a single moment of one individual’s childhood or adolescence is used as proxy. Sampling an early mineralising tooth might be better suitable to determine the place of birth and thus of origin, but it might be biassed by the breastfeeding signal (which is especially an issue for δ18O data (Britton et al. 2015; Pederzani and Britton 2019), see also Suppl. Text. 1E). The M2 or P2 was therefore targeted in some studies to specifically avoid this problem (Leggett 2021b; Schuh 2014: 87). Nonetheless, sampling only a later mineralising tooth might miss and thus underestimate mobility if it occurred during the very early childhood (Fig. 5 (C)). This is a reason why in some studies, at least two teeth reflecting two stages of the childhood and/or adolescence are sampled. Assessing the temporality of mobility during an individual’s life also informs about the context and required logistic of mobility: mobile children may for example indicate residential mobility or fosterage (Fig. 5 (B)), whereas mobility exclusively occurring during adulthood could indicate another socio-political or economic framework.

(A) Number of publications investigating various life stages depending on the research “category”. (B) Number of publications which detected the mobility of single individuals, groups, families and/or communities using information on diet and origin derived from different tissues and hence different life stages. (C) Number of publications which a percentage of non-local individuals from less than 10 to more than 50% using information on diet and origin derived from different tissues and hence different life stages

Because diet and especially the consumption of C4 plants is considered an important complementary information on a potential foreign origin and/or on various cultural habits or social status (see above), δ13C values from the dental enamel is often integrated into such studies (Schuh and Makarewicz 2016; Symonds et al. 2014). Adding δ13C and δ13N values from the bone collagen further enables to assess whether specific dietary habits are kept after arrival or if the diet of the individuals living in the same is homogeneous regardless of the origin. Combined with the various proxies and the archaeological context, this may inform about subsistence strategies, social structure and possibly about the degree of integration and cultural interaction of newcomers within their new residential area (Knipper et al. 2020; Leggett 2021a; Temkina 2021). Combining various proxies therefore enables more accurate narratives; this however implies the destruction of more skeletal material per individual and increases the analytical costs per individual as well.

Only in few cases, the results are only based on the last years of life—as reflected by the analysed bone material. In these cases, and especially when the data inform more directly on diet than on environmental settings (i.e. when only carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses are carried out on bone collagen), the possibility to actually detect mobility or at least a different geographic origin seems to be particularly limited (see above). Moreover, strontium isotope analyses carried out on bone apatite are sometimes assumed to represent an average value of the last years of life, but it is usually assumed that due to its porosity, the bone would be totally or partially influenced by the strontium isotope composition of the soil in which it is buried (see Suppl. Text 1F). 87Sr/86Sr values measured in human bones as a proxy for the last years of life should therefore be considered with caution or avoided.

To track the impact of migration

Studies that investigate the impact of migration events on local population mostly base their interpretation on information reflecting the last 5 to 25 years of life of the analysed individuals (Fig. 5 (A)). This is of course related to the method since carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses are carried out on bone collagen. But, this implies certain limitations in the interpretation since it is not possible to accurately distinguish locals from newcomers without additional analyses (see also Fig. 5 (A–C)) or to see if there was a significant change in dietary or cultural habits between childhood and the period documented in the bones for each individual. This limitation is balanced in studies integrating samples dating before, during and after the sought event (e.g. Fuller et al. 2010; Lightfoot et al. 2012; Varano et al. 2020).

On the other hand, studies considering only information about the potential local or non-local origin as reflected by data measured in dental enamel (i.e. from the childhood and/or adolescence) can only use the archaeological records to evaluate the “impact” of the newcomers at the site—which is certainly a good starting point, but presents the abovementioned limitations. Combining the archaeological and historical background with isotope data reflecting both childhood and the last years of life as well as various aspects of dietary and mobility patterns enhance the chance to get a more holistic picture (Guede et al. 2018; Hakenbeck et al. 2017) —even though a diachronic approach would be required to more accurately evaluate the impact of newcomers on local cultural settings.

To sum up, the complementary information about the origin of food (with strontium and/or oxygen isotope analyses of dental enamel) and diet (with carbon isotope analyses of dentine collagen and/or dental enamel) during childhood is a powerful approach to identify outliers and to estimate (or at least to potentially exclude) the possible region of origin of newcomers (Leggett 2021b; Symonds et al. 2014; Winter-Schuh and Makarewicz 2019). Some studies furthermore showed that the combination of strontium and oxygen isotope analyses of dental enamel with carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses of bone collagen led to a better understanding of the cultural relationship between local and non-local individuals at one site (Alt et al. 2014; Knipper et al. 2020). In a further step forward, recent studies demonstrated the strength of multi-tissues and multi-isotope analyses in combining various lines of evidence for a more accurate insight into the complexity of early medieval societies and thus a more robust reconstruction of mobility patterns, dietary habits and subsistence strategies (Hakenbeck et al. 2017; Maxwell 2019; Noche-Dowdy 2015).

To determine isotope baselines

Since a large number of publications are already dedicated to the determination of local baselines—particularly for strontium isotopes (Bataille et al. 2020; Snoeck et al. 2020; Willmes et al. 2018) but also for oxygen isotopes (Bowen and Wilkinson 2002; Lightfoot and O’Connell 2016; Pederzani and Britton 2019) and carbon and nitrogen isotopes (Ambrose and Norr 1993; Bird et al. 2021; Bownes et al. 2018)—this paper will not discuss this particularly complex issue (see a short overview on baseline determination and the related issue of defining the meaning of “local” in Suppl. Text 1G).

Advances in Migration Period archaeology

Based on the distinction between mobility and migration by L. A. Gregoricka (Gregoricka 2021), this section aims at verifying whether evidence for Völkerwanderungen and their impact are provided by isotope studies (see also Suppl. Text 1D).

Identifying mobility patterns

In this dataset, about three-quarters of the sites and publications revealed less than one-third of non-local individuals within their sample (Fig. 6 (B))—provided that the other individuals were “true locals”. In these early medieval communities, a mean value of 31% non-locals is attested, but at some sites (i.e. in approximately 30% of the publications providing a percentage of non-locals) over one-third and sometimes even over half of the individuals were not born locally. At several sites, the observed mobility rate is even assumed to be underestimated due to the similarities in isotope ratios over several or large geographical areas (Knipper et al. 2020; Schuh and Makarewicz 2016).

Number of publications (from the “Migration” category) presenting the various aspects of mobility patterns. Some publications showed different results at the different sites and were hence counted as often as required. (A) Mobility rate as described in the various publications. (B) Violin plot with jitter plot of the percentage of non-locals at 32 sites (left) and number of publications showing different percentage ranges of non-local individuals (right). (C) Frequency of the demographic scale of mobility at the publication level. (D) Number of publications revealing various geographic scales of mobility. (E) Correlation between observed and expected origin of the sampled individuals at the publication level. (F) Number of publications showing or rejecting a correlation between foreign cultural attribute and foreign isotope signature. (G) Number of publications which supported or rejected Völkerwanderungen narratives

Because the percentage of non-local individuals can be difficult to assess due to issues related to baseline determination (Suppl. Text 1G), even percentage indications should be considered with caution—and might not necessarily be comparable between sites (Lightfoot and O’Connell 2016; Slovak and Paytan 2012). In general, the mobility rate might therefore need to be revised upwards. In this context, the application of only carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses appears to be the less adequate method to track mobility patterns (Fig. 6), whereas the only application of strontium and/or oxygen isotope analyses may be considered too restrictive to some extent (Fig. 6 (B, F)). The combination of diverse isotope systems seems to enhance the chance of identifying non-local individuals, whereas the only application of carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses is the less adequate approach (Fig. 6 (B)).

It is noteworthy that, even though a considerable mobility rate can be observed at least at some early medieval sites, the overall mobility rate (Leggett 2021a: 175–200) is not necessarily higher than during previous or later periods (Early Neolithic: Borić and Price 2013; Depaermentier et al. 2020; Neil et al. 2020); Bronze Age: (Cavazzuti et al. 2021; Gerling 2015: 210–225; Price et al. 2004); Iron Age: (Hrnčíř and Laffoon 2019; Panagiotopoulou et al. 2018); Roman Period (Eckardt et al. 2014; Killgrove and Montgomery 2016; Stark et al. 2020) (see also Suppl. Text 1H).

Regarding the demographic scale of mobility, the mobility of single individuals is the most often identified pattern at both the publication and site level (Fig. 6 (C) and Suppl. Tab. 1F). In contrast, mobile communities or families (which are difficult to disentangle) were assumed in only a few cases. This infers that the observed mobility patterns mostly do not correspond to one or several waves of massive migration events as usually expected from the written sources. This is also supported by the often high diversity of origin among the newcomers within a site, which mostly did neither correspond to the expected nor to any shared geographic origin (Fig. 6 (D–E)). Because assumptions regarding potential homelands of given groups based on both written sources and archaeological records is highly controversial (Curta 2020) and because the exact origin of individuals cannot yet be assessed by means of isotope analyses due to data equifinality (Evans et al. 2010; Madgwick et al. 2021; Montgomery 2010), such observations should be considered with caution.

A high diversity of origin or dietary practices among non-locals further challenges the traditional Völkerwanderungen narratives since socio-political and economic triggers can be considered instead. In particular, new scale-based approaches into baseline determination furthermore offer great potential to distinguish between regional and long-distance mobility (Depaermentier et al. 2020, 2021; Snoeck et al. 2016). Hence, beside the frequently attested long distance or supra-regional scale related to observed mobility patterns, movements at the regional scale have become increasingly visible (Fig. 6 (D)). This supports the idea that the self-sufficient economy became the rule and at least partially replaced the market-based Roman system (Akeret et al. 2019; Maxwell 2019: 1; Rösch 2008) and also fits the model of translocal communities suggested for prehistoric societies (Furholt 2018).

As expected from previous archaeological (Curta 2020; Lucy 2000, 2005) and large-scale bioarchaeological (Leggett 2021a) studies, this corpus confirmed that there is usually no clear interrelationship between foreign cultural attributes and foreign isotope values (Fig. 6 (F)) and hence that the diversity of cultural attributes and practices is related to other social, economic, political or religious factors rather than to ethnicity and origin. Similarly, approximately half of the publications rejected the hypothesis of massive migration events or could only partly support Völkerwanderungen narratives, whereas about 15% considered these as a possible interpretation among others (Fig. 6 (G)). Among the publications that supported traditional narratives, the interpretation seems to be mostly based on a high mobility rate and/or on the fact that people might have come from distant regions (Fig. 6 (A, B, D)).

Pitfalls in assessing the impact of newcomers

As emphasised above, looking for the impact of newcomers, i.e. of new ethnic or cultural groups, on local population and environment implies that there are indeed newcomers at the site and that these can be associated to the assumed new entity. But due to the general application of only carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses in such studies, there is usually no way to verifying whether the sampled individuals were locals or newcomers with this approach. And even in the studies including strontium and/or oxygen isotope analyses, there is usually no clear evidence for the expected migration events (Fig. 7 (A)). Here, most studies did not check the Völkerwanderungen narratives, but considered those as the background and granted starting point of the study (Fig. 7 (B)).

(A) Number of publications presenting the various aspects of mobility patterns that could inform about migration events versus other types of mobility. This refers only to publications from the “impact” category. (B) Left: Number of publications presenting various types of impact of the arrival of new people into the studied area. In this case, the results of the studies from the “Migration” category that also addressed the question of this potential impact were added to get a better overview of the overall narratives related to this question. Right: Number of publications supporting or rejecting Völkerwanderungen narratives

In this context, human (or animal) showing C4 plants signatures within a C3 plants ecosystem are usually considered to be potential migrants (Crowder et al. 2020; Hakenbeck et al. 2010; Plecerová et al. 2020). However, isotope studies from both this dataset (Suppl. Figure 1) and previous studies showed that the consumption of C4 plants in small to important proportions by whole communities or by small groups or single individuals is attested during (Leggett 2021a: 219–231; Leggett 2022; Lightfoot et al. 2012) but also long before the Early Middle Ages (Filipović et al. 2020; Kirleis et al. 2022; Lightfoot et al. 2013). Even though southern and eastern Europe represent the region with the most suitable environmental and climatic settings for millet cultivation (Filipović et al. 2020; Lightfoot et al. 2013; Miller 2015) and hence the most important input of millet in diet (Leggett 2022), C4 crops were often used at least as complement to C3 plants in other regions (Suppl. Figure 1).

The variability of practices even on the small scale suggests that millet consumption may depend on the environmental and climatic settings, the socio-economic context (Adamson 2004; Alaica et al. 2019; Alexander et al. 2019) and the cultural habits and preferences (Hakenbeck et al. 2017; López-Costas and Alexander 2019; Paladin et al. 2020). Its short growth period, high crop yield, high resistance and high nutritious effect (Filipović et al. 2020; Lightfoot et al. 2013; Miller 2015) also suggest that millet cultivation could be introduced by the local community for practical reasons or as a response to environmental (e.g. the Late Antique Little Ice Age (Büntgen et al. 2016)) and socio-economic factors (García-Collado 2016; Hakenbeck et al. 2017; Paladin et al. 2020). Because there can be several reasons why C4 plants are (suddenly) consumed or cultivated at one site, it might be difficult to determine that a C4 plants’ signal—and a shift in economic system related to the cultivation of C4 plants—is directly related to newcomers (Leggett 2022), especially when the main argument consists in associating millet to a given ethnic or cultural group.

New paradigms

Even though there is a risk that mobility remains underestimated by means of isotope analyses, the lack of evidence for Völkerwanderungen demonstrates the urgent need to move away from an outdated perception of this period. In this context, the results of isotope analyses reveal so-far unexcepted or at least underestimated patterns. For example, a continuous flux of migration or mobility (Fig. 8 (B)) is attested all over Europe during the Early Middle Ages (Leggett 2021a: 310, 328; Montgomery et al. 2005; Winter-Schuh and Makarewicz 2019). This is usually associated with the stream or chain migration theory, according to which people from the same home or even the same family are likely to follow previously emigrated relatives instead of moving to unknown, random places (Anthony 1990, 1997). This concept changes our perception regarding this highly complex and dynamic period. It also highlights the need to systematically consider the age at death and an exact chronology when studying sites. Systematic, large-scale aDNA analysis may help better understanding this pattern.

Frequency of (A) the diverse gendered mobility and dietary patterns and the related interpretation in terms of exogamy, (B) the alternative mobility types, (C) the further cultural and environmental factors influencing the isotope variability in human tissues and (D) the impact of the social status on isotope variability at the publication level

Another rising trend (especially since 2015) is to interpret isotope and archaeological data as evidence for integration and mutually beneficial cultural interactions between locals and newcomers. Here, however, the new paradigms of “integrated migrants” replacing the concept of “barbarian invaders” might also be influenced by the current political situation in Europe (Gregoricka 2021; Steinacher 2019) and by the fear that scientific results might be misused in public media (Frieman and Hofmann 2019). Even though the combination of mobility patterns and dietary habits can help to better seize the integration of foreign individuals and their cultural interactions with the local community after their arrival (Alt et al. 2014; Hakenbeck et al. 2017; Knipper et al. 2020), one should avoid perpetuating stereotypes (Gregoricka 2021) regardless of their positive or negative connotation.

The identification of regional to long-distance marriage networks derived from observed gendered mobility and/or dietary patterns (Fig. 8 (A–B)) represents another common alternative. This dataset as well as a large-scale study conducted in England demonstrated that there is no universal rule in this case either: depending on the region and the chronology, males and females sometimes show varied degree of mobility or originated from distinct regions (Leggett et al. 2022). Overall, female exogamy is more often considered probable than male exogamy. Further studies based on other archaeobiological proxies supported the hypothesis that female exogamy played an important role at the time (Knipper et al. 2017; Stewart 2022; Veeramah et al. 2018). Gendered mobility or dietary patterns could further suggest different roles and activities of males and females in the society (Noche-Dowdy 2015: 101). Mobile men were for example often interpreted as soldiers (Crowder et al. 2020; Eckardt et al. 2015; Vohberger 2011: 203). However, this hypothesis is not supported at each site, even where it is strongly expected (Montgomery et al. 2005). Moreover, it is noteworthy that gendered mobility or dietary patterns were often not attested at all (Fig. 8 (A); Suppl. Text 1E).

Among the other possible interpretations for the results of isotope analyses, slavery (Amorim et al. 2018; Maxwell 2019), fosterage (Hemer et al. 2013), the residential mobility of whole families (Schweissing and Grupe 2003; Vohberger 2011: 192) and religious triggers or monastery networks (Hemer et al. 2013; Symonds et al. 2014) are only seldom mentioned. In general, diverse socio-political networks and the role of economic activities such as trade or husbandry strategies are assumed (Budd et al. 2004; Leggett 2021a: 331–335; Paladin et al. 2020) (see also Fig. 8 (B)). Especially the abovementioned evidence for long-distance movements was often related to trade (Figs. 6 (D) and 8 (B–C)), which suggests that the Roman infrastructures and especially the transport of goods and people over land, rivers and sea still played a considerable role in early medieval economy (Kempf 2019; Nol 2021; Quast 2009). Here, both archaeological (Depaermentier and Brather-Walter 2022; Hedeager 2000; Martin 2020) and biomolecular evidence (Amorim et al. 2018; Symonds et al. 2014; Vytlačil et al. 2021) suggest that such large-scale networks might have principally involved the elites and royal or urban centres.

A correlation between social status and specific mobility or dietary habits is however often rejected (Fig. 8 (D)). Provided that the identification of the social status was reliable (which can be very problematic (Brownlee 2020, 2021), see also Suppl. Text 1E), this aligns with the results of a large-scale study conducted in England (Leggett and Lambert 2022). In hierarchical societies and/or especially in geologically and environmentally heterogeneous regions, there is a potential for groups or families within one community to have access to various resources or to distinct parts of the catchment area of a site, which would be visible in the isotope ratio. Even though early medieval communities are assumed to be mainly self-sufficient farmers (Akeret et al. 2019; Kempf 2018)—as supported by the high proportion of locally organised societies within this sample (Fig. 8 (B))—the possibility that animals or further foods were imported cannot be neglected (Kempf 2019; Steuer 1997; van Lanen et al. 2016), particularly within elite contexts. The impact of various subsistence strategies at a site (Alt et al. 2018; Hakenbeck et al. 2017), the availability of various food resources (Leggett 2021a: 82–173; Paladin et al. 2020) as well as further cultural practices including cooking, brewing and stewing (Brettell et al. 2012; Leggett 2021a: 201–216) can also be an important trigger for local isotope variability in human skeletal tissues (Fig. 8 (C)).

Conclusion

This literature review shows that a combination of various approaches involving isotope analyses allows for getting insight into so-far not assessable aspects such as the demographic (single individuals, groups), geographic and temporal (seasonal, cyclical, continuous, etc.) scale of mobility. Overall, isotope data support the concept of a highly dynamic society, characterised by a sometimes considerable mobility rate, which was however restricted to single individuals or groups of persons. A major part of the population was, on the contrary, organised at the regional scale. In this context, the observed mobility patterns may reflect socio-political, marriage, religious, economic and/or military networks. They might also be restricted to the elite given the associated costs—or on the contrary to people with lower social status who sought better living conditions.

Based on the comparison between isotope and archaeological data, new paradigms emphasising the integration of and mutually beneficial interaction with newcomers as well as the flexibility and adaptability of early medieval societies are increasingly replacing the concept of a catastrophic impact of migrations on local populations. But in this case, the current political situation or “Zeitgeist” may influence the narrative derived from the interpretation of the results. In general, it would be worth trying to study early medieval societies without systematically using labels such as “Franks”, “Lombards” or even “barbarian newcomers” as the first, fundamental information that shapes the whole research. The diversity of both mobility and dietary patterns and the fact that origin in terms of place of birth was not necessarily a key aspect for social organisation suggest that the scale of socio-cultural and economic interactions between early medieval communities was hitherto considerably underestimated. This goes along with a need to redefine the concepts of cultural group and communities in archaeological research.

The exponential production of isotope data and the development of open access repositories (Cocozza et al. 2022; Leggett et al. 2021; Leggett et al. 2022; Salesse et al. 2018; Snoeck et al. 2022) facilitate the integration and comparison of several datasets for future large-scale, synthetic studies and for more comprehensive small-scale investigations. The interpretation of stable and radiogenic isotope data still requires a fundamental understanding of the ecological and environmental settings and their impact on isotope baselines, which is one of the most important challenges for future research.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Code availability

All software and R-packages used for the analysis are cited in the text.

References

Adamson MW (2004) Food in medieval times. Greenwood Publishing Group, Westport

Akeret Ö, Deschler-Erb S, Kühn M (2019) The transition from Antiquity to the Middle Ages in present-day Switzerland: The archaeobiological point of view. Quatern Int 499:80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2017.05.036

Alaica AK, Schalburg-Clayton J, Dalton A, Kranioti E, Graziani Echávarri G, Pickard C (2019) Variability along the frontier: stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratio analysis of human remains from the Late Roman-Early Byzantine cemetery site of Joan Planells, Ibiza, Spain. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 11:3783–3796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-018-0656-0

Alexander MM, Gutiérrez A, Millard AR, Richards MP, Gerrard CM (2019) Economic and socio-cultural consequences of changing political rule on human and faunal diets in medieval Valencia (c. fifth–fifteenth century AD) as evidenced by stable isotopes. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 11:3875–3893. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-019-00810-x

Alt KW, Knipper C, Peters D, Müller W, Maurer A-F, Kollig I, Nicklisch N, Müller C, Karimnia S, Brandt G, Roth C, Rosner M, Mende B, Schöne BR, Vida T, von Freeden U (2014) Lombards on the move–an integrative study of the migration period cemetery at Szólád, Hungary. PLoS ONE 9:e110793. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110793

Alt KW, Müller C, Held P (2018) Ernährungsrekonstruktion anhand stabiler Isotope von Kohlenstoff und Sticktstoff an frühmittelalterlichen Bestattungen der Gräberfelder von Tauberbischofsheim-Dittigheim und Szólád. In: Drauschke J, Kislinger E, Kühtreiber K, Kühtreiber T, Scharrer-Liška G, Vida T (eds) Lebenswelten zwischen Archäologie und Geschichte: Festschrift für Falko Daim zu seinem 65. Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums, Mainz, Geburtstag, pp 869–885

Ambrose SH, Norr L (1993) Experimental evidence for the relationship of the carbon isotope ratios of whole diet and dietary protein to those of bone collagen and carbonate. In: Lambert JB, Grupe G (eds) Prehistoric human bone: archaeology at the molecular level. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, s.l., pp 1–37

Amorim CEG, Vai S, Posth C, Modi A, Koncz I, Hakenbeck S, La Rocca MC, Mende B, Bobo D, Pohl W, Baricco LP, Bedini E, Francalacci P, Giostra C, Vida T, Winger D, von Freeden U, Ghirotto S, Lari M, Barbujani G, Krause J, Caramelli D, Geary PJ, Veeramah KR (2018) Understanding 6th-century barbarian social organization and migration through paleogenomics. Nat Commun 9:3547. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06024-4

Anthony DW (1990) Migration in archeology: the baby and the bathwater. Am Anthropol 92:895–914. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1990.92.4.02a00030

Anthony DW (1997) Prehistoric migration as a social process. In: Chapman J, Hamerow H (eds) Migrations and invasions in archaeological explanation. Archaeopress, Oxford, pp 21–32

Bataille CP, Crowley BE, Wooller MJ, Bowen GJ (2020) Advances in global bioavailable strontium isoscapes. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 555:109849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.109849

Bentley RA (2006) Strontium isotopes from the Earth to the archaeological skeleton: a review. J Archaeol Method Theory 13:135–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-006-9009-x

Bird MI, Crabtree SA, Haig J, Ulm S, Wurster CM (2021) A global carbon and nitrogen isotope perspective on modern and ancient human diet. PNAS 118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2024642118

Borić D, Price TD (2013) Strontium isotopes document greater human mobility at the start of the Balkan Neolithic. PNAS 110:3298–3303. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211474110

Bowen GJ, Wilkinson B (2002) Spatial distribution of δ18O in meteoric precipitation. Geol 30:315. https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030%3c0315:SDOOIM%3e2.0.CO;2

Bownes J, Clarke L, Buckberry J (2018) The importance of animal baselines: using isotope analysis to compare diet in a British medieval hospital and lay population. J Archaeol Sci Rep 17:103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.10.046

Brettell R, Montgomery J, Evans J (2012) Brewing and stewing: the effect of culturally mediated behaviour on the oxygen isotope composition of ingested fluids and the implications for human provenance studies. J Anal at Spectrom 27:778. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2ja10335d

Britton K, Richards MP (2020) Introducing archaeological science. In: Richards M, Britton K (eds) Archaeological science: an introduction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 3–10

Britton K, Fuller BT, Tütken T, Mays S, Richards MP (2015) Oxygen isotope analysis of human bone phosphate evidences weaning age in archaeological populations. Am J Phys Anthropol 157:226–241. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22704

Brownlee EC (2020) The dead and their possessions: the declining agency of the cadaver in Early Medieval Europe. Eur j Archaeol 23:406–427. https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2020.3

Brownlee E (2021) Connectivity and funerary change in Early Medieval Europe. Antiquity:1–18. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.153

Brubaker R (2002) Ethnicity without groups. Eur J Sociol 43:163–189

Budd P, Millard A, Chenery C, Lucy S, Roberts C (2004) Investigating population movement by stable isotope analysis: a report from Britain. Antiquity 78:127–141. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X0009298X

Büntgen U, Myglan VS, Ljungqvist FC, McCormick M, Di Cosmo N, Sigl M, Jungclaus J, Wagner S, Krusic PJ, Esper J, Kaplan JO, de Vaan MAC, Luterbacher J, Wacker L, Tegel W, Kirdyanov AV (2016) Cooling and societal change during the Late Antique Little Ice Age from 536 to around 660 AD. Nat Geosci 9:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2652

Burmeister S (2016) Archaeological research on migration as a multidisciplinary challenge. Medieval Worlds 4:42–64. https://doi.org/10.1553/medievalworlds_no4_2016s42

Cahill Wilson J, Standish CD (2016) Mobility and migration in Late Iron Age and Early Medieval Ireland. J Archaeol Sci Rep 6:230–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.02.016

Cavazzuti C, Hajdu T, Lugli F, Sperduti A, Vicze M, Horváth A, Major I, Molnár M, Palcsu L, Kiss V (2021) Human mobility in a Bronze Age Vatya ‘urnfield’ and the life history of a high-status woman. PLoS ONE 16:e0254360. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254360

Childe VG (1951) Man makes himself, 2nd edn. New American Library, New York

Cocozza C, Cirelli E, Groß M, Teegen W-R, Fernandes R (2022) Presenting the compendium Isotoporum Medii Aevi, a multi-isotope database for Medieval Europe. Sci Data 9:354. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01462-8

Crowder KD, Montgomery J, Filipek KL, Evans JA (2020) Romans, barbarians and foederati: new biomolecular data and a possible region of origin for “Headless Romans” and other burials from Britain. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 30:102180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.102180

Curta F (2020) Migrations in the archaeology of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in the Early Middle Ages: (some comments on the current state of research). In: Preiser-Kapeller J, Reinfandt L, Stouraitis Y (eds) Migration histories of the Medieval Afroeurasian Transition Zone. Brill, pp 101–138

Czére O, Fawcett J, Evans J, Sayle K, Gundula Müldner G, Hall M, Will B, Mitchell J, Noble G, Britton K (2021) Multi-isotope analysis of the human skeletal remains from Blair Atholl, Perth and Kinross, Scotland: insights into the diet and lifetime mobility of an Early Medieval individual. Tayside Fife Archaeol J 27:31–44

Depaermentier MLC, Kempf M, Bánffy E, Alt KW (2020) Tracing mobility patterns through the 6th-5th millennia BC in the Carpathian Basin with strontium and oxygen stable isotope analyses. PLoS ONE 15:e0242745. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242745

Depaermentier MLC, Kempf M, Bánffy E, Alt KW (2021) Modelling a scale-based strontium isotope baseline for Hungary. J Archaeol Sci 135:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2021.105489

Depaermentier MLC, Brather-Walter S (2022) Beziehungsgeflechte im frühen Mittelalter: Eine Fallstudie aus Basel. Zeitschrift für Archäologie des Mitttelalters (ZAM) Jahrgang 49:1–81

Díaz-Andreu M, Lucy S, Babić S, Edwards DN (eds) (2005) Archaeology of identity: approaches to gender, age, status, ethnicity and religion. Routledge, London, New York

Dutton PE (2018) The identification of persons in Frankish Europe. Early Medieval Europe 26:135–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/emed.12263

Eckardt H, Müldner G, Lewis M (2014) People on the move in Roman Britain. World Archaeol 46:534–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2014.931821

Eckardt H, Müldner G, Speed G (2015) The Late Roman Field Army in Northern Britain? Mobility, material culture and multi-isotope analysis at Scorton (N Yorks). Britannia 46:191–223. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0068113X1500015X

Evans JA, Montgomery J, Wildman G, Boulton N (2010) Spatial variations in biosphere 87Sr/86Sr in Britain. J Geol Soc 167:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1144/0016-76492009-090

Filipović D, Meadows J, Corso MD, Kirleis W, Alsleben A, Akeret Ö, Bittmann F, Bosi G, Ciută B, Dreslerová D, Effenberger H, Gyulai F, Heiss AG, Hellmund M, Jahns S, Jakobitsch T, Kapcia M, Klooß S, Kohler-Schneider M, Kroll H, Makarowicz P, Marinova E, Märkle T, Medović A, Mercuri AM, Mueller-Bieniek A, Nisbet R, Pashkevich G, Perego R, Pokorný P, Pospieszny Ł, Przybyła M, Reed K, Rennwanz J, Stika H-P, Stobbe A, Tolar T, Wasylikowa K, Wiethold J, Zerl T (2020) New AMS 14C dates track the arrival and spread of broomcorn millet cultivation and agricultural change in prehistoric Europe. Sci Rep 10:13698. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70495-z

Frieman CJ, Hofmann D (2019) Present pasts in the archaeology of genetics, identity, and migration in Europe: a critical essay. DOI: 10.1080/00438243.2019.1627907. World Archaeol 51:528–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2019.1627907

Fuller BT, Márquez-Grant N, Richards MP (2010) Investigation of diachronic dietary patterns on the islands of Ibiza and formentera, Spain: evidence from carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratio analysis. Am J Phys Anthropol 143:512–522. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21334

Furholt M (2018) Translocal communities – exploring mobility and migration in sedentary societies of the European Neolithic and Early Bronze Age. Praehistorische Zeitschrift 92:304–321. https://doi.org/10.1515/pz-2017-0024

García-Collado MI (2016) Food consumption patterns and social inequality in an Early Medieval rural community in the centre of the Iberian Peninsula. In: Quirós Castillo JA (ed) Social complexity in Early Medieval rural communities: the north-western Iberia archaeological record. Archaeopress Archaeology, Oxford, pp 59–78

Gartner (2019) Hype Cycle Research Methodology. https://www.gartner.com/en/research/methodologies/gartner-hype-cycle. Accessed 28 April 2022

Gerling C (2015) Prehistoric mobility and diet in Western Eurasia steppes 3500 to 300 BC: an isotopic approach. Topoi, volume 25. De Gruyter, Berlin, Boston

Goffart W (1989) Rome’s fall and after. Ronceverte, London

Goffart W (2006) Barbarian tides: the migration age and the later Roman Empire. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, Pa, The Middle Ages series

Graceffa A (2008) Antiquité barbare, l’autre Antiquité: L’impossible réception des historiens français (1800–1950). Anabases 8:83–104

Gregoricka LA (2021) Moving forward: a bioarchaeology of mobility and migration. J Archaeol Res 29:581–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10814-020-09155-9

Grupe G, Christiansen K, Schröder I, Wittwer-Backofen U (2012) Anthropologie. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg

Guede I, Ortega LA, Zuluaga MC, Alonso-Olazabal A, Murelaga X, Solaun JL, Sanchez I, Azkarate A (2018) Isotopic evidence for the reconstruction of diet and mobility during village formation in the Early Middle Ages: Las Gobas (Burgos, northern Spain). Archaeol Anthropol Sci 10:2047–2058. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-017-0510-9

Hakenbeck S (2013) Potentials and limitations of isotope analysis in Early Medieval archaeology. Post-Classical Archaeologies 3:109–125

Hakenbeck S, McManus E, Geisler H, Grupe G, O’Connell T (2010) Diet and mobility in Early Medieval Bavaria: a study of carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes. Am J Phys Anthropol 143:235–249. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21309

Hakenbeck SE, Evans J, Chapman H, Fothi E (2017) Practising pastoralism in an agricultural environment: an isotopic analysis of the impact of the Hunnic incursions on Pannonian populations. PLoS ONE 12:e0173079. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173079

Halffman CM, Velemínský P (2015) Stable isotope evidence for diet in Early Medieval Great Moravia (Czech Republic). J Archaeol Sci Rep 2:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2014.12.006

Halsall G (2005) The Barbarian invasions. In: Fouracre P (ed) The new Cambridge medieval history: volume 1: c.500–c.700. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 35–55

Halsall G (2007) Barbarian migrations and the Roman West, 376–568. Cambridge medieval textbooks. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge

Halsall G (2010) The technique of Barbarian settlement in the fifth century: a reply to Walter Goffart. J Late Antiquity 3:99–112. https://doi.org/10.1353/jla.0.0060

Halsall G (2014) Two worlds become one: a ‘counter-intuitive’ view of the Roman Empire and ‘Germanic’ migration. Ger Hist 32:515–532. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerhis/ghu107

Heather PJ (2010) Empires and barbarians: the fall of Rome and the birth of Europe. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York, Auckland etc

Heather PJ (2018) Barbarian migrations. In: Nicholson O (ed) The Oxford dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom, Barbarian migrations

Hedeager L (2000) Migration Period Europe: the formation of a political mentality. In: Frans CWJ, Nelson J (eds) Theuws. Rituals of power from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle ages. E. J. Brill, Leiden, pp 15–57

Hemer KA, Evans JA, Chenery CA, Lamb AL (2013) Evidence of Early Medieval trade and migration between Wales and the Mediterranean Sea region. J Archaeol Sci 40:2352–2359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2013.01.014

Hines J (2013) Anglo-Saxon Graves and Grave Goods of the 6th and 7th Centuries AD: A Chronological Framework: Dataset. Archaeology Data Service, York

Hrnčíř V, Laffoon JE (2019) Childhood mobility revealed by strontium isotope analysis: a review of the multiple tooth sampling approach. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 11:5301–5316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-019-00868-7

Iacumin P, Galli E, Cavalli F, Cecere L (2014) C4 -consumers in southern Europe: the case of Friuli V.G. (NE-Italy) during early and central Middle Ages. Am J Phys Anthropol 154:561–574. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22553

Katzenberg MA, Grauer AL (eds) (2018) Biological anthropology of the human skeleton. John Wiley & Sons Inc, Hoboken, NJ, USA

Kempf M (2018) Migration or landscape fragmentation in Early Medieval eastern France? A case study from Niedernai. J Archaeol Sci Rep 21:593–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.08.026

Kempf M (2019) Paradigm and pragmatism: GIS-based spatial analyses of Roman infrastructure networks and land-use concepts in the Upper Rhine Valley. Geoarchaeology 34:797–808. https://doi.org/10.1002/gea.21752

Killgrove K, Montgomery J (2016) All roads lead to Rome: exploring human migration to the Eternal City through biochemistry of skeletons from two Imperial-Era Cemeteries (1st-3rd c AD). PLoS ONE 11:e0147585. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147585

Kirleis W, Dal Corso M, Filipovic D (2022) Millet and what else? The wider context of the adoption of millet cultivation in Europe. Scales Transform, vol 14. Sidestone Press, Leiden

Knipper C, Maurer A-F, Peters D et al (2012) Mobility in Thuringia or mobile Thuringians. A strontium isotope study from Early Medieval Central Germany. In: Kaiser E, Burger J, Schier W (eds) Population dynamics in prehistory and early history: new approaches by using stable isotopes and genetic. De Gruyter, Berlin, Boston, pp 287–310

Knipper C, Mittnik A, Massy K, Kociumaka C, Kucukkalipci I, Maus M, Wittenborn F, Metz SE, Staskiewicz A, Krause J, Stockhammer PW (2017) Female exogamy and gene pool diversification at the transition from the Final Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age in central Europe. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:10083–10088. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1706355114

Knipper C, Koncz I, Ódor JG, Mende BG, Rácz Z, Kraus S, van Gyseghem R, Friedrich R, Vida T (2020) Coalescing traditions-Coalescing people: community formation in Pannonia after the decline of the Roman Empire. PLoS ONE 15:e0231760. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231760

Kristiansen K (2014) Towards a new paradigm? The third science revolution and its possible consequences in archaeology. Curr Swed Archaeol 22:11–34. https://doi.org/10.37718/CSA.2014.01

Leggett S (2021a) ‘Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you who you are’: a multi-tissue and multi-scalar isotopic study of diet and mobility in Early Medieval England and its European neighbours. Univ. Diss, University of Cambridge

Leggett S, Rose A, Praet E, Le Roux P (2021) Multi-tissue and multi-isotope (δ13 C, δ15 N, δ18 O and 87/86 Sr) data for Early Medieval human and animal palaeoecology. Ecology 102:e03349. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3349

Leggett S (2021b) Migration and cultural integration in the Early Medieval cemetery of Finglesham, Kent, through stable isotopes. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-021-01429-7

Leggett S (2022) A hierarchical meta-analytical approach to Western European dietary transitions in the first millennium AD. Eur J Archaeol:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2022.23

Leggett S, Lambert T (2022) Food and power in Early Medieval England: a lack of (isotopic) enrichment. Anglo-Saxon England in press:1–33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263675122000072

Leggett S, Hakenbeck S, O’Connell T (2022) Large-scale isotopic data reveal gendered migration into Early Medieval England c AD 400–1100. OSF Preprints June 9. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/jzfv6

Lightfoot E, O’Connell T (2016) On the use of biomineral oxygen isotope data to identify human migrants in the archaeological record: intra-sample variation, statistical methods and geographical considerations. PLoS ONE 11:e0153850. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153850

Lightfoot E, Šlaus M, O’Connell T (2012) Changing cultures, changing cuisines: cultural transitions and dietary change in Iron Age, Roman, and Early Medieval Croatia. Am J Phys Anthropol 148:543–556. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22070

Lightfoot E, Liu X, Jones MK (2013) Why move starchy cereals? A review of the isotopic evidence for prehistoric millet consumption across Eurasia. World Archaeol 45:574–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2013.852070

Lightfoot E, Šlaus M, Rajić Šikanjić P, O’connell TC (2015) Metals and millets: Bronze and Iron Age diet in inland and coastal Croatia seen through stable isotope analysis. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 7:375–386

López-Costas O, Alexander M (2019) Paleodiet in the Iberian Peninsula: exploring the connections between diet, culture, disease and environment using isotopic and osteoarchaeological evidence. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 11:3653–3664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-019-00886-5

Lucy S (2000) The Anglo-Saxon way of death: burial rites in Early England. The History Press Ltd, Sutton

Lucy S (2005) Ethnic and cultural identities. In: Díaz-Andreu M, Lucy S, Babić S, Edwards DN (eds) Archaeology of identity: approaches to gender, age, status, ethnicity and religion. Routledge, London, New York, pp 89–109

Madgwick R, Lamb A, Sloane H, Nederbragt A, Albarella U, Parker Pearson M, Evans J (2021) A veritable confusion: use and abuse of isotope analysis in archaeology. Archaeol J 178:361–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/00665983.2021.1911099

Makarewicz CA, Sealy J (2015) Dietary reconstruction, mobility, and the analysis of ancient skeletal tissues: expanding the prospects of stable isotope research in archaeology. J Archaeol Sci 56:146–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2015.02.035

Martin TF (2020) Casting the net wider: network approaches to artefact variation in post-Roman Europe. J Archaeol Method Theory. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-019-09441-x

Martinón-Torres M, Killick D (2015) Archaeological theories and archaeological sciences. In: Gardner A, Lake M, Sommer U, Martinón-Torres M, Killick D (eds) The Oxford handbook of archaeological theory. Oxford University Press, pp 1–17

Maxwell AB (2019) Exploring variations in diet and migration from Late Antiquity to the Early Medieval Period in the Veneto, Italy: a biochemical analysis. Zugl. Diss.: University of South Florida. Graduate Theses and Dissertations, South Florida

Meier T (2020) Methodenprobleme einer Chronologie in Süddeutschland: Eine Diskussion anhand von Matthias Friedrich » Archäologische Chronologie und historische Interpretation : Die Merowingerzeit in Süddeutschland » (2016). Germania 98:237–290

Miller NF (2015) Rainfall seasonality and the spread of millet cultivation in Eurasia. Iran J Archaeol Stud 5:1–10

Montgomery J (2010) Passports from the past: investigating human dispersals using strontium isotope analysis of tooth enamel. Ann Hum Biol 37:325–346. https://doi.org/10.3109/03014461003649297

Montgomery J, Evans JA, Powlesland D, Roberts CA (2005) Continuity or colonization in Anglo-Saxon England? Isotope evidence for mobility, subsistence practice, and status at West Heslerton. Am J Phys Anthropol 126:123–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20111

Müldner G (2013) Stable isotopes and diet: their contribution to Romano-British research. Antiquity 87:137–149. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00048675

Neil S, Evans J, Montgomery J, Scarre C (2020) Isotopic evidence for human movement into Central England during the Early Neolithic. Eur J Archaeol 23:512–529. https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2020.22

Noche-Dowdy L (2015) Multi-isotope analysis to reconstruct dietary and migration patterns of an Avar population from Sajópetri, Hungary, AD 568–895. Master of Arts Thesis, University of South Florida

Nol H (2021) Long distance trade in the Early Medieval period: a general introduction. In: Nol H (ed) Riches beyond the horizon, vol 4. Brepols Publishers. Turnhout, Belgium, pp 17–36

Ortega LA, Guede I, Zuluaga MC, Alonso-Olazabal A, Murelaga X, Niso J, Loza M, Quirós Castillo JA (2013) Strontium isotopes of human remains from the San Martín de Dulantzi graveyard (Alegría-Dulantzi, Álava) and population mobility in the Early Middle Ages. Quatern Int 303:54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2013.02.008

Paladin A, Moghaddam N, Stawinoga AE, Siebke I, Depellegrin V, Tecchiati U, Lösch S, Zink A (2020) Early Medieval Italian Alps: reconstructing diet and mobility in the valleys. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-019-00982-6

Panagiotopoulou E, Montgomery J, Nowell G, Peterkin J, Doulgeri-Intzesiloglou A, Arachoviti P, Katakouta S, Tsiouka F (2018) Detecting mobility in Early Iron Age Thessaly by strontium isotope analysis. Eur J Archaeol 21:590–611. https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2017.88

Pederzani S, Britton K (2019) Oxygen isotopes in bioarchaeology: principles and applications, challenges and opportunities. Earth Sci Rev 188:77–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.11.005

Plecerová A, Kaupová Drtikolová S, Šmerda J, Stloukal M, Velemínský P (2020) Dietary reconstruction of the Moravian Lombard population (Kyjov, 5th–6th centuries AD, Czech Republic) through stable isotope analysis (δ13C, δ15N). J Archaeol Sci: Rep 29:102062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.102062

Price TD, Burton JH, Bentley RA (2002) The characterization of biologically available strontium isotope ratios for the study of prehistoric migration. Archaeometry 44:117–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4754.00047

Price TD, Knipper C, Grupe G, Smrcka V (2004) Strontium isotopes and prehistoric human migration: the Bell Beaker Period in Central Europe. Eur J Archaeol 7:9–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461957104047992

Quast D (2009) Communication, migration, mobility and trade. Explanatory models for exchange processes from the Roman Iron Age to the Viking Age. In: Quast D (ed) Foreigners in Early Medieval Europe: thirteen international studies on Early Medieval mobility. Verlag des Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseums, Mainz, pp 1–26

Quirós Castillo JA, Ricci P, Sirignano C, Lubritto C (2012) Paleodieta e società rurali altomedievali dei Pasei Baschi alla luce dei marcatori isotopici di C e N (secoli V-XI). Archeologia Medievale 39:87–92

Reitsema LJ, Kozłowski T (2013) Diet and society in Poland before the state: stable isotope evidence from a Wielbark population (2nd c. AD). Anthropol Rev 76:1–22. https://doi.org/10.2478/anre-2013-0010

Rösch M (2008) New aspects of agriculture and diet of the Early Medieval period in central Europe: waterlogged plant material from sites in south-western Germany. Veg Hist Archaeobotany 17:225–238

Salesse K, Fernandes R, de Rochefort X, Brůžek J, Castex D, Dufour É (2018) IsoArcH.eu: an open-access and collaborative isotope database for bioarchaeological samples from the Graeco-Roman world and its margins. J Archaeol Sci Rep 19:1050–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.07.030

Schuh C (2014) Tracing human mobility and cultural diversity after the fall of the Western Roman Empire: a multi-isotopic investigation of Early Medieval cemeteries in the Upper Rhine Valley. Univ. Diss, Kiel

Schuh C, Makarewicz CA (2016) Tracing residential mobility during the Merovingian period: an isotopic analysis of human remains from the Upper Rhine Valley, Germany. Am J Phys Anthropol 161:155–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23017

Schweissing MM, Grupe G (2003) Stable strontium isotopes in human teeth and bone: a key to migration events of the late Roman period in Bavaria. J Archaeol Sci 30:1373–1383. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-4403(03)00025-6

Slovak NM, Paytan A (2012) Applications of Sr isotopes in archaeology. In: Baskaran M (ed) Handbook of environmental isotope geochemistry. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 743–768

Snoeck C, Pouncett J, Ramsey G, Meighan IG, Mattielli N, Goderis S, Lee-Thorp JA, Schulting RJ (2016) Mobility during the neolithic and bronze age in northern ireland explored using strontium isotope analysis of cremated human bone. Am J Phys Anthropol 160:397–413. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22977

Snoeck C, Ryan S, Pouncett J, Pellegrini M, Claeys P, Wainwright AN, Mattielli N, Lee-Thorp JA, Schulting RJ (2020) Towards a biologically available strontium isotope baseline for Ireland. Sci Total Environ 712:136248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136248

Snoeck C, Cheung C, Griffith JI, James HF, Salesse K (2022) Strontium isotope analyses of archaeological cremated remains – new data and perspectives. Data in Brief:108115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2022.108115

Stark RJ, Emery MV, Schwarcz H, Sperduti A, Bondioli L, Craig OE, Prowse T (2020) Imperial Roman mobility and migration at Velia (1st to 2nd c. CE) in southern Italy. J Archaeol Sci: Rep 30:102217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102217

Steinacher R (2019) Transformation or fall? Perceptions and perspectives on the transition from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. In: Brather-Walter S (ed) Archaeology, history and biosciences: interdisciplinary perspectives. W. De Gruyter, Berlin, Boston, pp 103–124

Steuer H (1997) Handel und Fernbeziehunge: Tausch, Raub und Geschenk. In: Archäologisches Landesmuseum Baden-Württemberg (ed) Die Alamannen: Ausstellungskatalog. Begleitband zur Ausstellung “Die Alamannen”, 14. Juni 1997 bis 14. September 1997, SüdwestLB-Forum, Stuttgart ; 24. Oktober 1997 bis 25. Januar 1998, Schweizerisches Landesmuseum Zürich ; 6. Mai 1998 bis 7. Juni 1998, Römisches Museum der Stadt Augsburg. Theiss, Stuttgart, pp 389–402

Stewart A (2022) Bridging the gap: using biological data from teeth to comment on social identity of archeological populations from early Anglo-Saxon. England. Ann Anat 240:151876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2021.151876

Symonds L, Price DT, Keenleyside A, Burton JH (2014) Medieval migrations: isotope analysis of Early Medieval skeletons on the Isle of Man. Mediev Archaeol 58:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1179/0076609714Z.00000000029

Temkina A (2021) The Early Medieval transition: diet reconstruction, mobility, and culture contact in the Ravenna Countryside, Northern Italy. Master of Arts Thesis, University of South Florida

van Klinken GJ, Richards MP, Hedges REM (2000) An overview of causes for stable isotopic variations in past European human populations. Environmental, ecophysiological, and cultural effects. In: Ambrose SH, Katzenberg MA (eds) Biogeochemical approaches to paleodietary analysis: advances in archaeological and museum science, New York, London, pp 39–63

van Lanen RJ, Jansma E, van Doesburg J, Groenewoudt BJ (2016) Roman and early-medieval long-distance transport routes in north-western Europe: modelling frequent-travel zones using a dendroarchaeological approach. J Archaeol Sci 73:120–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.07.010

Varano S, Angelis F de, Battistini A, Brancazi L, Pantano W, Ricci P, Romboni M, Catalano P, Gazzaniga V, Lubritto C, Santangeli Valenzani R, Martínez-Labarga C, Rickards O (2020) The edge of the Empire: diet characterization of medieval Rome through stable isotope analysis. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-020-01158-3