Abstract

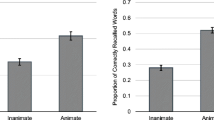

Animacy effects in memory correspond to the observation that animates (e.g., cow) are remembered better than inanimates (e.g., pencil). Although the ultimate explanation of these effects seems to be well-documented, clear evidence that would support one or other of the proximate explanations of animacy effects has proven difficult to obtain. Here, we focused on the richness-of-encoding account of animacy effects in memory, which assumes that animates are recalled better than inanimates because the former are encoded with many more distinct associations with other items (i.e., richer memory traces) than the latter. Our goal was to provide further evidence for this account by replicating and extending the analyses of Meinhardt, Bell, Buchner, and Röer (2020) showing that more ideas are generated in response to animate than inanimate words and, importantly, that this generation process mediates the better recall of animates over inanimates. In line with the richness-of-encoding account, we successfully replicated the finding that more ideas were produced in response to animates than inanimates. Even though there is some evidence that the generation of ideas mediates animacy effects in memory, we also report findings from reanalyses of previous studies (Bonin et al., Experimental Psychology, 62, 371–384, Bonin et al., 2015; Gelin et al., Memory, 25, 2–18, Gelin et al., 2017; Gelin et al., Memory, 27, 209–223, Gelin et al., 2019) which—although supporting mediation—show that the number of ideas generated in response to animate and inanimate words cannot reliably predict memory of these words when they are learned in different encoding contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A common practice is to base the decision on p-values obtained in bilateral tests. When parameter estimations agree with unilateral hypotheses, the associated unilateral p-values are equal to bilateral ones divided by two. Reasoning on the basis of unilateral tests makes it possible to get more powerful tests.

The number of ideas given by the participants was used as a proxy for the number of ideas per item.

For the current experiment, the animacy effect was also significant at .05 in the by-items analysis (p = 0361; d = .84).

To this end, we also explored another possibility through the information statistic H, which has been largely employed when measuring agreement between the names given to a specific picture of an object (e.g. Snodgrass & Vanderwart, 1980). However, the results obtained with the use of H generally outperformed those obtained with the variables described for the purpose of mediation (there were, however, no contradictions between them).

As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, it is possible that different encoding contexts (e.g., survival scenario, moving scenario) constrain the generation of ideas to different degrees—with animate words causing, on average, the production of more ideas than inanimate words—and that differences in the number of ideas generated in response to specific words may vary in different contexts. Apart from the observation that the interactions between animacy or tasks and the measures of generated ideas are never significant—which suggests that differences between animacy conditions and tasks are similar whatever the number of generated ideas—the current findings cannot be used directly to answer such a question. In the Gelin et al. (2017) studies, animacy effects did not differ across different encoding contexts (e.g., survival encoding, tour guide), suggesting that, perhaps, different contexts do not substantially modify the number of ideas produced in response to animate compared to inanimate words. However, this issue still has to be investigated in detail.

Nevertheless, before ending our discussion of this issue, we would like to indicate the results of a complementary analysis in which we took the number of different associates given for words as an index of richness-of-encoding. The scores were taken from the Bonin et al. (2013), in which participants were instructed to name the first word that came to mind in response to any given word. (We had scores available for only 9 animates and 7 inanimates used in the present study.) We found that the correlations of the number of associates with recall rates were all significantly positive at .05, except in the intentional learning task (r = .41, p = .119), and that more associates were generated for animate words than for inanimate words, t(14) = 3.05, p = .0087. While the results were descriptively in line with those previously reported, that is to say direct effects of animacy lower than total effects and confidence intervals of indirect effects mostly positive, they were still too widely distributed.

References

Aka, A., Phan, T. D., & Kahana, M. J. (2021). Predicting recall of words and lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 47, 765–784.

Alario, F.-X., & Ferrand, L. (1999). A set of 400 pictures standardized for French: Norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity, visual complexity, image variability, and age of acquisition. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 31, 531–552.

Altarriba, J., & Avery, M. C. (2021). Divergent thinking in survival processing: Did our ancestors benefit from creative thinking? Evolutionary Psychology.

Baayen, R. H., Davidson, D. J., & Bates, D. M. (2008). Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language, 59, 390–412.

Balota, D. A., Pilotti, M., & Cortese, M. J. (2001). Subjective frequency estimates for 2,938 monosyllabic words. Memory & Cognition, 29, 639–647.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Blunt, J. R., & VanArsdall, J. E. (2021). Animacy and animate imagery improve retention in the method of loci among novice users. Memory & Cognition, 49, 1360–1369.

Bonin, P., Gelin, M., & Bugaiska, A. (2014). Animates are better remembered than inanimates: Further evidence from word and picture stimuli. Memory & Cognition, 42, 370–382.

Bonin, P., Gelin, M., Laroche, B., & Méot, A. (2015). The “how” of animacy effects in episodic memory animacy effects in memory. Experimental Psychology, 62, 371–384.

Bonin, P., Gelin, M., Dioux, V., & Méot, A. (2019). “It is alive!” Evidence for animacy effects in semantic categorization and lexical decision. Applied PsychoLinguistics, 40, 965–985.

Bonin, P., Méot, A., Ferrand, L., & Bugaïska, A. (2013). Normes d'associations verbales pour 520 mots concrets et étude de leurs relations avec d'autres variables psycholinguistiques. L'Année Psychologique, 113, 63–82.

Bonin, P., Peereman, R., Malardier, N., Méot, A., & Chalard, M. (2003). A new set of 299 pictures for psycholinguistic studies: French norms for name agreement, image agreement, conceptual familiarity, visual complexity, image variability, age of acquisition, and naming latencies. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 35, 158–167.

Bugaiska, A., Grégoire, L., Camblats, A. M., Gelin, M., Méot, A., & Bonin, P. (2019). Animacy and attentional processes: Evidence from the Stroop task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 72, 882–889.

Christian, J., Bickley, W., Tarka, M., & Clayton, K. (1978). Measures of free recall of 900 English nouns: Correlations with imagery, concreteness, meaningfulness, and frequency. Memory & Cognition, 6, 379–390.

DeYoung, C. M., & Serra, M. J. (in press). Judgments of learning reflect the animacy advantage for memory, but not beliefs about the effect. Metacognition and Learning.

Félix, S. B., Pandeirada, J. N., & Nairne, J. S. (2019). Adaptive memory: Longevity and learning intentionality of the animacy effect. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 31, 251–260.

Gelin, M., Bonin, P., Méot, A., & Bugaiska, A. (2018). Do animacy effects persist in memory for context? Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 71, 965–974.

Gelin, M., Bugaiska, A., Méot, A., & Bonin, P. (2017). Are animacy effects in episodic memory independent of encoding instructions? Memory, 25, 2–18.

Gelin, M., Bugaiska, A., Méot, A., Vinter, A., & Bonin, P. (2019). Animacy effects in episodic memory: Do imagery processes really play a role? Memory, 27, 209–223.

Guerrero, G., & Calvillo, D. P. (2016). Animacy increases second target reporting in a rapid serial visual presentation task. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 23, 1832–1838.

Hargreaves, I. S., Pexman, P. M., Johnson, J. C., & Zdrazilova, L. (2012). Richer concepts are better remembered: Number of features effects in free recall. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 73.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Guilford Press.

Jackson, R. E., & Calvillo, D. P. (2013). Evolutionary relevance facilitates visual information processing. Evolutionary Psychology, 11, 1011–1026.

Jersild, A. T. (1927). Mental set and shift. Archives of Psychology, 89, 5–82.

Judd, C. M., Kenny, D. A., & McClelland, G. H. (2001). Estimating and testing mediation and moderation in within-subject designs. Psychological Methods, 6, 115–134.

Kazanas, S. A., Altarriba, J., & O’Brien, E. G. (2020). Paired-associate learning, animacy, and imageability effects in the survival advantage. Memory & Cognition, 48, 244–225.

Lau, M. C., Goh, W. D., & Yap, M. J. (2018). An item-level analysis of lexical-semantic effects in free recall and recognition memory using the megastudy approach. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 71, 2207–2222.

Leding, J. K. (2019). Adaptive memory: Animacy, threat, and attention in free recall. Memory & Cognition, 47, 383–394.

Leding, J. K. (2020). Animacy and threat in recognition memory. Memory & Cognition, 48, 788–799.

Luke, S. G. (2017). Evaluating significance in linear mixed-effects models in R. Behavior Research Methods, 49, 1494–1502.

Madan, C. R. (2021). Exploring word memorability: How well do different word properties explain item free-recall probability? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 28, 583–595.

Meinhardt, M. J., Bell, R., Buchner, A., & Röer, J. P. (2018). Adaptive memory: Is the animacy effect on memory due to emotional arousal? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25, 1399–1404.

Meinhardt, M. J., Bell, R., Buchner, A., & Röer, J. P. (2020). Adaptive memory: Is the animacy effect on memory due to richness of encoding? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 46, 416–426.

Montoya, A. K., & Hayes, A. F. (2017). Two-condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: A path-analytic framework. Psychological Methods, 22, 6–27.

Nairne, J. S. (2010). Adaptive Memory: Evolutionary constraints on remembering. In B. H. Ross (Ed.), The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, (Vol 53) (pp. 1–32). Academic Press.

Nairne, J. S., & Coverdale, M. E. (2021). Adaptive memory: The mnemonic value of fitness-relevant processing. In M. Krause, K. L. Hollis, & M. R. Papini (Eds.), Evolution of learning and memory mechanisms. Cambridge University Press.

Nairne, J. S., & Pandeirada, J. N. S. (2008). Adaptive memory: Is survival processing special? Journal of Memory and Language, 59, 377–385.

Nairne, J. S., & Pandeirada, J. N. S. (2010). Adaptive memory: Ancestral priorities and the mnemonic value of survival processing. Cognitive Psychology, 61, 1–22.

Nairne, J. S., & Pandeirada, J. N. S. (2016). Adaptive memory: The evolutionary significance of survival processing. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11, 496–511.

Nairne, J. S., Pandeirada, J. N. S., & Fernandes, N. L. (2017a). Adaptive memory. In J. H. Byrne (Ed.), Learning and Memory: A Comprehensive Reference (Vol. 2, 2nd ed., pp. 279–293). Elsevier.

Nairne, J. S., VanArsdall, J. E., & Cogdill, M. (2017b). Remembering the living: Episodic memory is tuned to animacy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26, 22–27.

Nairne, J. S., VanArsdall, J. E., Pandeirada, J. N. S., Cogdill, M., & LeBreton, J. M. (2013). Adaptive memory: The mnemonic value of animacy. Psychological Science, 24, 2099–2105.

New, J., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2007). Category-specific attention for animals reflects ancestral priorities, not expertise. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 104, 16598–16603.

Noble, C. E. (1952). An analysis of meaning. Psychological Review, 59, 421–430.

Open Science Collaboration (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), [aac4716].

Paivio, A., Yuille, J. C., & Madigan, S. A. (1968). Concreteness, imagery, and meaningfulness values for 925 nouns. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 76(1, Pt.2), 1–25.

Pashler, H., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2012). Editors’ introduction to the special section on replicability in psychological science: A crisis of confidence? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 528–530.

Popp, E. Y., & Serra, M. J. (2016). Adaptive memory: Animacy enhances free recall but impairs cued recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 42, 186–201.

Popp, E. Y., & Serra, M. J. (2018). The animacy advantage for free-recall performance is not attributable to greater mental arousal. Memory, 26, 89–95.

Rawlinson, H. C., & Kelley, C. M. (2021). In search of the proximal cause of the animacy effect on memory: Attentional resource allocation and semantic representations. Memory & Cognition, 49, 1137–1152.

Röer, J. P., Bell, R., & Buchner, A. (2013). Is the survival-processing memory advantage due to richness of encoding? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39, 1294–1302.

Rubin, D. C., & Friendly, M. (1986). Predicting which words get recalled: Measures of free recall, availability, goodness, emotionality, and pronunciability for 925 nouns. Memory & Cognition, 14, 79–94.

Salthouse, T. A., Toth, J. P., Hancock, H. E., & Woodard, J. L. (1997). Controlled and automatic forms of memory and attention: Process purity and the uniqueness of Age-related influences. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 52B, P216–P228.

Snodgrass, J. G., & Vanderwart, M. (1980). A standardized set of 260 pictures: Norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity, and visual complexity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 6, 174–215.

Spector, A., & Biederman, I. (1976). Mental set and mental shift revisited. The American Journal of Psychology, 89, 669–679.

VanArsdall, J. E., Nairne, J. S., Pandeirada, J. N. S., & Blunt, J. R. (2013). Adaptive memory: Animacy processing produces mnemonic advantages. Experimental Psychology, 60, 172–178.

VanArsdall, J. E., Nairne, J. S., Pandeirada, J. N. S., & Cogdill, M. (2017). A categorical recall strategy does not explain animacy effects in episodic memory. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 70, 761–771.

Wilson, S. (2016). Divergent thinking in the grasslands: Thinking about object function in the context of a grassland survival scenario elicits more alternate uses than control scenarios. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 28, 618–630.

Yap, M. J., Tan, S. E., Pexman, P. M., & Hargreaves, I. S. (2011). Is more always better? Effects of semantic richness on lexical decision, speeded pronunciation, and semantic classification. Psychonomic Bulletin & Reviews, 18, 742–750.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interest Statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

The authors wish to thank Richard Ferraro and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on a previous version of the ms.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 15 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bonin, P., Thiebaut, G., Bugaiska, A. et al. Mixed evidence for a richness-of-encoding account of animacy effects in memory from the generation-of-ideas paradigm. Curr Psychol 41, 1653–1662 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02666-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02666-8